Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box

333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

Volume 18, No. 2 April, 1980

ANNUAL MEETING

MIDDLESEX CANAL ASSOCIATION

April 26, 1980 at 2:00 P.M.

at the Charles River Dam

Charlestown, Mass.

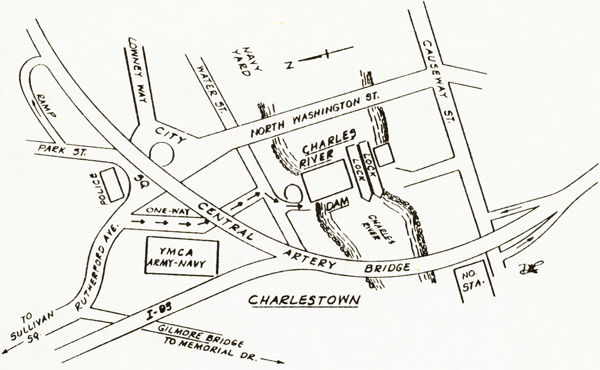

The annual meeting of the Middlesex Canal Association will take place on Saturday, April 26, 1980, at the Charles River Dam in Charlestown. (See directions below and map on back cover)

At 2:00 P.M., there will be a tour of the dam conducted by the superintendent, Clayton Stokes.

At 3:00 P.M., the business meeting will be held for the hearing of reports, the annual election of officers and directors, and any other business which may be brought before the meeting.

DIRECTIONS TO THE NEW CHARLES RIVER DAM

In going toward Boston on Route I-93, take the Mystic Avenue-Sullivan Square exit. Follow Mystic Avenue into Sullivan Square. Cross Cambridge Street and bear right into Rutherford Avenue. Follow Rutherford Avenue into City Square. Bear right at the YMCA, before Warren Street bridge approach, into the ramp to the Charles River Dam.

Approaching Charlestown from downtown Boston on the Expressway, after passing the Storrow Drive exit, hold the right lane and bear right at Tobin Bridge turnoff. Hold the right (slow!) lane and turn sharp right at the exit to the USS "Constitution." Turn right at foot of the ramp into Water Street. Turn right at the "Boston" sign, then left on Chelsea Street (1 block) into City Square. Go to the right of the bridge approach, into the ramp to Charles River Dam (formerly Warren Avenue).

Visitors may park inside the gate, but must leave before 4:00 P.M., when gates are locked for the night.

PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE

We are looking forward to meeting all of you with Mr. Clayton Stokes for a tour of the Charles River Dam on Saturday, April 26th, for our annual meeting.

A new worry for us all is the monumental threat to our National Archives. The National Archives and Records Service (NARS) under control of the General Services Administration plans the dispersal of records of MARS to Federal Records Centers around the country. This means the chilling prospect of scholars having to hop from city to city to obtain their information, instead of finding it all in one place. The fine National Archives and Records Service has worked hard for fifty years to build up our U.S. Archives. Please write your Representatives, Senators and Jimmy Carter requesting additional space and that the MARS be separated from the General Services Administration and made a separate agency.

We are pleased that the Middlesex Canal packet boat "Colonel Baldwin" will be running again at Baldwin's Landing in North Woburn, this summer on Sundays from July 6 through August 31 from 2:00 to 4:00 P.M. Be sure to plan your family reunions around rides on the Middlesex Canal, and look for an announcement of a special Canal Day and picnic in August.

The Nominating Committee is considering nominations for the annual meeting election. Please send your nominations and suggestion to Marion E. Potter, RR 2, Box 42, North Billerica, Mass. 01862.

Fran Ver Planck

President

IN THIS ISSUE we present an innovation: the entire issue is devoted to a lengthy article on one subject, one which has long been of interest to the Editor: the development of steamboats on the Middlesex Canal and the collaboration of John L. Sullivan, the Superintendent of the Middlesex Canal, and Samuel Morey, the Orford inventor.

The author, Alice Doan Hodgson, is a resident of Orford, N.H., Morey's home town, and has devoted herself to spreading Morey's fame. She has published several magazine articles in ANTIQUES and many monographs including Orford, New Hampshire: A Most Beautiful Village and Samuel Morey, Inventor Extraordinary.

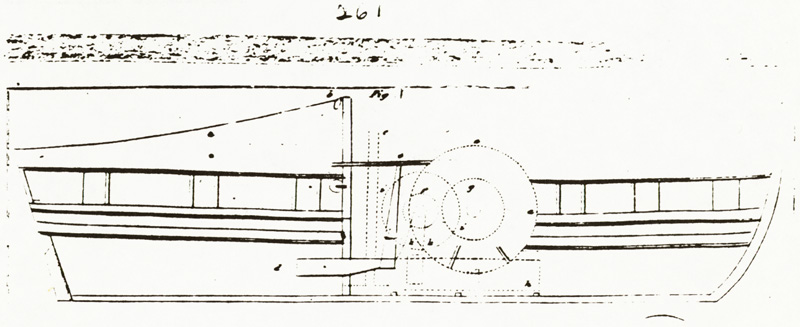

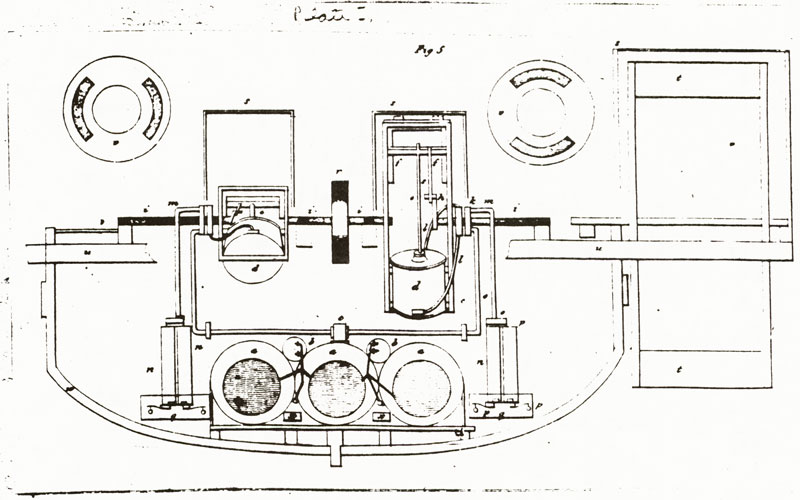

The Illustrations accompanying the article are taken from J.L. Sullivan's article on the Revolving Steam Engine published in Benjamin Silliman's American Journal of Science and Arts in 1819. The full-page drawing on page 6 is a cross section of a steamboat showing the steam engine with drive shaft and 2 cylinders above the boilers. One paddle wheel is shown on the right. The smaller drawing at the end of the article is a longitudinal section of a steamboat. The larger dotted circle is the paddle wheel.

THE JOHN L. SULLIVAN & SAMUEL MOREY CONNECTION

by Alice Doan Hodgson

Samuel Morey of Orford, New Hampshire, a self-taught civil engineer, inventor and mill owner, collaborated with John L. Sullivan, agent and engineer of the Middlesex Canal, on various projects from about 1815 through 1820 when Sullivan resigned the agency and went south to promote steam towboats on the Santee and Congaree rivers in South Carolina. The two men may have become acquainted earlier than 1815 through a mutual interest in canals. In 1791 Morey was in charge of planning and constructing a canal on the Connecticut River at Bellows Falls in Vermont. Work on it began the next year and was completed in 1802 when it opened with great fanfare. The first flat boats, entering stern first as instructed, were transported around the falls with the help of seven locks. Perhaps Morey went to inspect the work being done on the Middlesex Canal at the same time, looking for guidance for his own work, and thus met Sullivan.

Another tie that surely bound the two men together was their common adversary, Robert Fulton. In 1793 Morey had launched on the Connecticut River at Orford a log dugout steamboat having a paddle wheel at the bow. In 1797 he built a steamboat at New York with a stern paddle wheel. Chancellor Livingston was one of several passengers to ride on the boat. He expressed satisfaction with her performance and requested that Morey attempt to increase her speed. This Morey achieved by the use of two paddle wheels, a method he successfully and publicly demonstrated on the Delaware River. Unfortunately for Morey, Livingston went to Paris in 1801 as minister to France where he met Robert Fulton. The rest is history. Morey was righteously indignant over his treatment by Livingston and Fulton. He would have been in sympathy with Sullivan's en-counter with Fulton and delighted that Sullivan gave Fulton his comeuppance. It was in 1813 that a controversy arose over Fulton's and Sullivan's applications to the Secretary of State for steam towboat patents. Both men claimed priority and arbitrators were appointed to settle the case. James Hillhouse was chosen by Secretary of State James Monroe; Eli Whitney was Fulton's choice: and Theodore Dwight was Sullivan's choice. They met at the house of John Bennett in Hartford, Connecticut, December 1, 1813. Fulton did not appear but was represented by his attorney and agent, John D. Lacey, Esq. Sullivan appeared as his own representative. For two days the arbitrators considered the evidence, exhibits and arguments. The hearing was then adjourned to obtain more perfect documents from the office of the Secretary of State. On December 15th they met at the home of Justin Butler in New Haven and "having duly considered the matters thus referred to us, with the evidence and arguments offered in support of the same, we (the arbitrators) do find the said John L. Sullivan in the case set forth in the papers herein annexed is entitled to receive a Patent, and we do award that the same be granted him accordingly."

Altogether Sullivan and Morey had many similar interests. The first documented evidence of this is a letter written by Sullivan to Morey from Boston November 8, 1815. On July 14th of the same year, Morey had received two patents, one for tide and water wheels, the other for a revolving steam engine. Sullivan's letter deals with both subjects. It begins with a discouraging statement:

"I should commence this letter with much pleasure had I anything cheering to communicate but disappointment, tho temporary is an unpleasant theme."

He goes on to say that the mill wheel, being tested in Billerica at a gristmill owned by the Middlesex Canal Proprietors, was not operating satisfactorily due to poor workmanship, but the man who constructed it was "bound in honor to make it go true." Sullivan then tells of a steam engine model that was ready for trial the previous month. The steam rose rapidly and high. The engine made about thirty strokes while unattached to any appliance: "The 2nd day it carried the paddle wheel & machinery, but too feebly for work, the boat was not in the water. It worked so feebly that I was unwilling to risk its reputation without some improvements." He was preparing an air pump and condenser, and he hoped, by the end of the month, his communication might be more agreeable. The engineer had not yet finished the plate of the wheel but it would soon be done. "….everything in this world takes time," he wrote "It is only by patience and perseverance that we arrive at results as you well know." A postscript asks, "What should you think of publishing this winter a description of the principle of your engine."

Sullivan did not write his proposed description of Morey's revolving steam engine until 1819, an eloquent example of how much time everything takes. Meanwhile another letter from Sullivan to Morey dated March 28, 1816, reveals that Morey had been down to inspect Sullivan's work. They were trying out an engine that was probably larger than the model mentioned in Sullivan's previous letter. During their test of the engine, an iron cog wheel gave way. Sullivan writes, ".... after parting from you I tried her again, and the swelling, or expansion, of the center piece broke the outside rim of the iron cog wheel - the center of which gave way, when you were there." Sullivan had made an alteration "at some expense and it works better but still by no means strong enough.... I have determined however to finish it, with condensers and cover in the Cylinders & Boiler & if it does not go strong enough for my purpose then, it may answer for some other."

Morey had sent one of his mechanics, a Mr. Ladd, to Sullivan with a letter which Sullivan acknowledged, saying, "He has been with me to Chelmsford and I am pleased with him...." Chelmsford may have been the testing site of Sullivan's boat powered by the steam engine. Mr. Ladd saw it in operation and Sullivan reported to Morey: "Mr. Ladd is himself surprised that it does not go with more force."

A model from which the engine was being constructed was also giving trouble. Says Sullivan, "I have advised Mr. Ladd to take your model from Mr. Dearborn's and carry it to you. I believe it is all to pieces. I wish you would send one that would work better - or not give out as this did. We excited a great deal of attention, and it seems desirable that people should see one in operation. However I have learned not to be so sanguine as I have been in the success of any mechanical contrivance - I am after several years labour in as much uncertainty as ever - but not discouraged."

Morey applied himself to improving the performance of his engine by experimenting with a new condenser and a boiler for generating high pressure steam. Sullivan wrote to him on November 21, 1816, regarding a patent for the boiler. , He was worried that someone "at the southward" might hear of it and construct one before Morey had patented the improvement, in which case "it would have been publickly known", and it was doubtful if his patent would then hold. Sullivan also advised Morey to take out a separate patent for his condenser "because if a patent contains several things and there proves to be any defect or defeat of one the whole goes." Apparently he had already drafted a patent specification and sent it to Morey. He writes, "I do not seek your confidence, or desire to take on me any more business than I have, and have endeavoured to forward your views in sending up the draft only as a friend, and in my hopes sometime or other of using the Merrimack and Connecticut."

Here at last is evidence that Sullivan with Morey's help was contemplating the use of steamboats on the Merrimack and Connecticut rivers. His concern over Morey's delay in taking out patents was due to his knowledge that a Mr. Curtis had invented a new engine of a rotary kind that was in operation at Brown's shipyard in New York. In a former letter Sullivan asks Morey to let him know his impression of the Curtis engine, should he see it, as he was "going to the southward."

Morey's boiler for generating high pressure steam was finally patented March 13, 1817. A second patent granted simultaneously was for a tide and current water wheel for driving mills and machinery with or without a dam. He had asked for help from Sullivan and his brother, George, in writing the specification of the wheel to which request Sullivan replied, "I will mention your wishes to George respecting the specification of the wheel - I do not understand it quite well enough to draft it and am perhaps too much engaged in the engine. I will help him if he can attend to it, but I think you can do it better than either."

Sullivan had sent a workman to Morey at Orford "to learn of you your latest improvements.... I would thank you to let him understand your last model....The present seems to be a great opportunity for you to perfect and establish your engine and I hope you will succeed." He understood the cylinder had been cast "but nothing done to it. You will have to wait a good while for them & they say they are waiting to have from you the size of the piston rod. I hope the winter will not wholly pass without accomplishing your experiment, and I confess it is possible unless you stir them up."

The winter passed and the summer, too, while Morey continued his experiments. It was not until the following winter that Morey was able to "perfect and establish" his engine. He. gave several demonstrations of his revolving steam engine at the Charlesown Navy Yard in February, 1818, applying its power to a saw which cut through a large log in record time. Among the eminent people who saw the engine perform was Capt. Isaac Hull, commander of the Constitution and Col. Amos Binney whose scientific interests were well-known. A certificate affirming the success of the engine and signed by Amos Binney, Isaac Hull, Joseph Barker and Amasa Woodworth is dated February 7, 1818. It reads:

"The Subscribers have repeatedly seen the performance of the Rotary Steam Engine invented and patented to Samuel Morey, erected at the Navy-Yard at Charlestown, and which, though incomplete, and without a , Condenser, having a Cylinder of only one foot stroke, nine inches in diameter, has cut one hundred and twenty strokes of the Saw per minute, through a log of one foot fifteen inches diameter.

"This engine is particularly simple in its construction, and very manageable. It appears to us peculiarly well adapted to Vessels and Boats. It also has an improved Boiler which generates steam with amazing rapidity."

Sullivan was so satisfied with Morey's engine that he purchased the patent right to manufacture it. In March, 1818, on his way to a legislative session at Albany to campaign for the repeal of Livingston's steam-boat monopoly, he wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Evening Post expressing his views on the monopoly and detailing the patented inventions he was determined to introduce into extensive operation, including on the waters of New York that were monopolized by Livingston at that time.

"I hold by purchase", he wrote, "the Invention of Samuel Morey Esq... His Rotary Engine is on a new and simple plan...by its lightness and motion it is peculiarly well adapted to boats and vessels of every size." He mentions Morey's lined boiler that uses less water and creates double the steam, also "his invention of Gas Fire, or as he call it in his specification, The American Water Burner." Sullivan states that it creates a great and intense flame easily governed and directed into the flue of a boiler. Furthermore, it is comparatively cheap and very useful to canal steamboats where all space that could be spared was needed for freight.

He extols the virtues of steam towboats as a safe, fast and inexpensive mode of transportation. The deck of a luggage boat could be partially occupied with a comfortable but not splendid cabin for passengers having goods on board. It was preferable, he pointed out, "to avoid the inconveniences and dangers, however small, of having the moving power in the same boat." The towed boat would "glide smoothly and swiftly over the water, without any rumbling, trembling or jarring...." There could be different classes of boats, some for excursion passengers who might have separate staterooms, others entirely appropriated to a party of friends. The laborer or emigrant seeking the richer soil of the interior might go with his family in the engine boat at a very low price, or free of expense.

In a few more months Sullivan would launch a steam towboat on the Connecticut River at Hartford, but she would not be operated by Morey's revolving steam engine. Sullivan may have become impatient while waiting for Morey to perfect his engine, despite his contention that everything takes time and only patience and perseverance could achieve results. In any case, he purchased a steam engine from Oliver Evans in Philadelphia and started to build the Experiment at Hartford. On November 10, 1818, the Hartford Courant announced: "Last week was launched from the ship-yard in this City, the first steamboat ever built on the Connecticut River. It is designed for a tow boat to ply between this City and the mouth of the River."

If Morey read the report, he may have thought of his little log dugout steamboat churning the waters of the Connecticut River and wanted to shout that the Experiment was not the first ever built on the river. However, his irritation would have been assuaged to learn that the Experiment was not satisfactory as a towboat and was to be converted to passenger service. A year later, the inadequacy of the Evans engine was expressed in Sullivan's own words, " ... the same boilers which once carried a twenty horse engine of Evans' in my first steam tow-boat, that could not be made to tow more than one boat, now applied to a small single revolving engine, can tow four boats faster than that one was carried and consume not half so much fuel."

This was written in October, 1819, and published the following year by Yale's Professor Benjamin Silliman in his American Journal of Science and Arts. Previously another article by Sullivan had been published in the Journal entitled "On the Revolving Steam Engine, recently invented by SAMUEL MOREY, and patented to him on the 14th July, 1815, with four Engravings." In it he describes Morey's engine and its use of the expansive force of steam for the purpose of navigation. By that time, Sullivan was building two more steam towboats and equipping them with Morey's engine, having established a manufactory "for their kind only." One boat was to be used on the Merrimack River, the other on the Connecticut. In explaining the type of construction suitable for towboats, Sullivan says, "It is not necessary to crowd the engine into the after-part of the boat, the boilers may be placed forward; and near them, or over them, the Cylinder etc. The power is then communicated to the stern-wheel by a long shaft, supported on, or immediately under, the deck. This arrangement gives room for loading both behind and before the boiler and engine, and equalizes the burden. This is the actual arrangement of the Merrimack boat."

The Enterprise being built at Hartford was 70 feet long, 21 feet wide and 136 tons. The engine, with its boilers, occupied a space 16 feet by 12 feet, or 1/8th of the boat. The two cylinders of 17 inch diameters and 18 inch strokes revolved three times a minute and were hung on the timbers of the deck over the boilers. Sullivan states that steam at fifty pounds will give a hundred horse power, and says, "The revolving engine makes up in activity what in other engines is supplied by magnitude."

The Merrimack was operating by June of 1819, a month earlier than the launching of the Enterprise on the Connecticut River. On June 13 the Merrimack left the Canal Head at Chelmsford towing two boats and adding another loaded boat the next day. She proceeded up the Merrimack River and arrived at Concord, N.H., on the 15th, leaving for the return trip the 23rd. The Concord Patriot of June 22nd records that "Citizens of Concord have for two weeks past been gratified with the appearance for the first time of a steamboat in our river. A good portion of the ladies and gentlemen in town availed themselves of the very polite invitation of the proprietors to take pleasure rides up and down the river for two or three miles."

Sullivan's log of the pleasure trips taken on various days gives their distances as 7 miles up river in 1 hr. 15 min. with 22 members of the General Court aboard; 7½ miles up river in 1 hr. 15 min. with 32 passengers; 8 miles up river with 157 passengers and a band of music in two boats in tow; 6 miles upstream with a loaded boat in tow and 70 passengers, returning with 91 passengers; up and down the river towing two boats, with awnings and 211 passengers including the Governor and Council; finally, at 5 A.M. on the day before leaving Concord, 7 miles up and down river with a party of members, and in the afternoon 215 passengers on board with music.

The Enterprise was launched on the Connecticut River in July, 1819, The Hartford Courant reported: "We have the pleasure to announce, that the Hartford Steam Boat, with the revolving engine, built by the Connecticut Company, made her first movement on Friday, last - and went at the rate of six miles an hour, notwithstanding the wood used was not seasoned. The gas fire made from tar, was found a very useful auxiliary. We understand she will shortly be in readiness to take passengers to the seacoast."

A week later the Hartford Times gave an account of the Enterprise after she had attracted attention by an extended excursion on the river: "The Steam Boat Enterprise, of Hartford, on Friday last, made a trip to Middletown. The machinery of this Boat is the patented revolving engine - the first that has been made on a large scale. It works admirably, with a steady, equable motion, without any jarring effect, and with as little noise as is possible, in a machine of this magnitude."

In Sullivan's second article on the revolving steam engine written in October, 1819, and published by Professor Silliman in 1820, he says, "In the Hartford boat, we used the Tar or Gas fire with good effect, but I am not able to state yet, precisely the proportion of saving. The men about the engine however, thought it equal to as much again wood as they used." An added note by Silliman states: "We understand that Mr. Sullivan and Mr. Morey in the investigation of the economy of the liquid fuel of steam engines, or tar and steam fire, made some discoveries and improvements which bid fair to be very useful and economical. They are in practice in a steam engine which carries the recently invented self directing lathe, which makes ships' blocks and other irregularly formed articles."

The revolutionary gas fire made from tar or, in Professor Silliman's words, tar and steam fire, was an invention patented by Morey December 11 1817. He called it The American Water Burner, as noted by Sullivan in his letter to the editor; of the New York Evening Post in March, 1818. The next month Sullivan wrote about the invention in a letter to Silliman which was published in 1819. Entitled "On a new Means of Producing Heat and Light, with an Engraving", it explained the method of using tar and steam to produce fuel, "as recently invented by Mr. Samuel Morey", and described the device Morey had constructed for the purpose. Three months after composing his letter to Silliman and before it appeared in the Journal, Sullivan wrote to J.F. Dana, M.D., of Cambridge on the subject o Morey's water gas discovery. Dr. Dana's interest was engaged and he published a paper in August, 1818, about The American Water Burner, saying that Morey had informed Sullivan a year or so previously of "his discovery of a method of burning water" and that Sullivan, knowing Morey to be acquainted with chemical science, entered into Morey's subject with some confidence. "These gentlemen after making experiments and employing various combustible substances, as tar, rosin, oil, etc. to mix with steam, have brought this apparatus to its present state of perfection.... The flame, although the combustible substances issue from so small an orifice, like that in the jet of a blow-pipe, is as large as that of a common smith's fire, and is unaccompanied with smoke."

On May 4, 1819, Morey himself wrote to Professor Silliman on the subject of his water gas. He wrote a second letter on March 28, 1820, and the two papers were published in Silliman's Journal that year. Morey described the construction and performance of his Water Burner and gave details of his experiments in producing the gas. He lists his use of tar, rosin, alcohol, fat or tallow oil, mineral coal, pitch-pine wood, birch bark knots and seeds of pumpkin, flax and sunflower plants. He tells of heating and lighting his home with the gas and says it could also be effective for lighting streets, for heating the water of steam engine boilers and as a fuel for cooking stoves. He foretold the coming event of central heating by his statement that heat could be piped from the burner to any desired location.

There has been confusion over the newfangled fuel used by Sullivan for his steamboat boilers. Morey's discovery of water gas was made half a century before it was finally understood and manufactured commercially. It is no wonder that people blamed burning tar for smoke issuing from the Merrimack's smokestack when actually the water gas flame was smokeless. The boiler must have been fired by wood at the time the smoke was observed. More recently a writer suggested that the tar fire would have gummed up the works of the steam engine. It is apparently difficult for anyone to understand that the tar did not burn but was only heated and its vapor combined with steam and oxygen to produce water gas. The misunderstanding was carried to absurdity when Morey was first experimenting with his device. People derided him for trying to burn water, and when they saw his flame burning pure and white, they thought he was using magic water from a secret spring.

However, Sullivan understood Morey's invention and helped with his experiments. Among the many substances they tested for evaporation into vapor, Morey preferred spirits of turpentine while Sullivan favored tar, so it was tar that was decided upon to produce water gas for heating the boilers of the Merrimack and Enterprise. When it came time to apply for a patent, Sullivan was one of the witnesses to the specification of The American Water Burner. Perhaps he helped Morey to draft the papers as well.

After the launchings of the Merrimack and Enterprise, the collaboration between Sullivan and Morey continued for another year or two. Sullivan, realizing perhaps that steam towboats on the Merrimack and Connecticut rivers were not proving commercially profitable, began to build a boat intended for use on southern waters. A letter written to Morey November 4, 1820, indicates that Sullivan was equipping his new boat with Morey's revolving engine.

"I was very sorry," he wrote, "not to see you at the boat, which the weather prevented, and that you left town without my being able to meet your wishes & my own but it so happened that I was never more pressed by a variety of engagements than at that period. My boat is still doing. I should have been glad of your opinion upon her. The bad weather a month back has retarded her progress exceedingly but I think it cannot be over a fortnight e'er she is complete."

"Much depends on the demonstration of the power of the engine and the plan of the boat in which I have given the machine every advantage, and if there is time between her being complete and my departure I hope that you will come down."

The letter continues with a response to a request Morey had made to Sullivan for money. Perhaps Sullivan had failed to pay for his purchase of the patent right to manufacture the revolving steam engine which, reputedly, amounted to $5,000, or it may be that Morey expected payment for their combined work on the steam towboats. Whatever the reason, Sullivan thought Morey's request might be "perfectly proper, tho unexpected - but under the circumstances - you may think it expedient & just to recollect, that with more exertion than usual I have no returns yet for anything I have purchased of your invention - and am actually doing more than any other person could or would do to establish its reputation and derive to you considerable emolument. Were I neglecting the pursuit, you might well despair of that - but in a moment so critical I incline to think you will find your ultimate interest best consulted, in suspending your requisition, which can have no utility till we shall find a time favourable & suitable to the inter-change of papers which our agreement included. I don't yet despair of bringing much to pass under our several patents, but it is a work of time & labour."

"I shall have much pleasure in making an early communication of the operation of the engine if it does well. Meanwhile I enclose a printed description which I have had occasion to distribute a little. And I should be glad of your remarks thereon if you will do me that favor."

The printed description is not among Morey's papers, nor is there any way of knowing whether he received the payment he requested from Sullivan. It is known that Sullivan sold at least one of the revolving steam engines he manufactured. It was in use at the New England Glass Works in East Cambridge in 1819. In his article to Professor Silliman on Morey's revolving steam engine, Sullivan cites as an example of its power "the engine working at the glass manufactory in this vicinity, the cylinder of which has one foot stroke and nine inches diameter, and is at least a ten horse power, working with fifty pounds." If Sullivan made any profit from selling the engine, it was no doubt consumed in the expenses of building the Merrimack and Enterprise and the boat destined for southern waters.

In 1822 Morey heard from Sullivan again. He had taken his boat under her own steam down the coast to South Carolina in excellent time where she was in use towing large river barges laden with bales of cotton. He wrote that thus far the boat had performed satisfactorily ascending the Santee and Congaree rivers towing heavy loads against a strong current.

This is the last knowledge we have of the Sullivan-Morey connection. Sullivan later became an associate engineer of the United States Board of Internal Improvements. Morey abandoned steam power in favor of the unprecedented internal combustion engine he invented and patented in 1826, an outcome of experiments with his Water Burner which accidentally exploded one day when he introduced too much oxygen into it. He promptly set about devising an engine to make use of that explosive power and succeeded in propelling a boat with it at a rate of seven or eight miles an hour.

Had Morey and Sullivan expended their time, money and energies on towboats operated by Morey's internal combustion engines, their success would have astonished a world that refused to accept the innovative power until more than half a century had passed.