Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

Middlesex Canal Association P.O.

Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 47 No. 3 |

April 2009 |

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

by Nolan Jones, President

603-672-7051

The Board of Directors meets the first Wednesday of most months at 3:30pm in the Museum. Members and friends are welcome to attend and give us your comments.

Space for our museum remains our most serious problem and will remain so for a few months at least, and perhaps for a few years. We are looking for increased rentals to help us pay our rent in the near term. Please consider scheduling your next major social event in our museum. Contact information is given elsewhere in this issue.

Our Spring Walk is planned for April 25 in Winchester and Medford.

Our Annual Meeting is scheduled for May 3. The program will be on Restoration of Historic Canals by Dave Barber, formerly a member of our Board and now President of the American Canal Society. He will be followed by Tom Raphael, chairman of the Middlesex Canal Commission, describing our plans for the Middlesex Canal.

Over 30 people from the Lexington Historical Society visited our museum on March 31st. We provided a program and explanations of our various exhibits. Reports were that it was a good experience for all. We would be happy to have groups from other cities and towns visit the museum.

Several months ago we received a grant to develop curriculum materials on the Middlesex Canal for elementary school students. This effort is going well and will culminate in teacher workshops next summer.

We find that there is limited knowledge of the Middlesex Canal and the "canal era" of the early 1800s. Four of us are available to give illustrated talks on various canal subjects to groups. I would like to present talks to all the historical societies along our route within the next year. You can reach us through the museum, our website or the contact information above.

A few of us are members of other Canal Societies. Our calendar contains information about events being conducted by some of these. If any of you would like to know more about what is going on elsewhere, please send us an inquiry through the museum, our website or the contact information above.

The 2009 World Canals Conference will be in Serbia in late September.

Like the US Marine Corps, we are looking for a few good men and women to serve on our Board of Directors and in other positions. Please contact me if you or someone you know would be willing to serve.

Nolan

TABLE OF CONTENTS

President's Message (Nolan Jones)

Calendar of Events

Project Update, Middlesex Canal Commission (Tom Raphael)

Loammi Baldwin's 1795 Progress Report on the Construction of the Middlesex Canal

(David Dettinger)

Letters First Published in the Boston Daily Advertiser #2 (transcribed by Howard

Winkler)

James Sullivan's Birthplace (Howard Winkler)

The Baldwin Apple

A New Baldwin Apple Orchard for the Sanborn House (Sue Clark)

Wife-Swapping on the Ohio & Erie (Canal Fulton, as told by Dillow Robinson)

Raft Lock? What's a Raft Lock? (Bill Gerber)

A Tribute to Jane Boyd Drury (Bill Gerber)

Miscellany

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

175th Anniversary, Delaware and Raritan Canal - See http://www.dandrcanal.com/programs.html for an impressive schedule of varied activities sponsored by the several organizations involved.

April 19-May 2 – Thru-hike, C&O Canal; reservations required; Barbara Sheridan, <membership at candocanal dot org>; 301-752-5436.

April 24-26 – CSNYS Spring Field Trip, the Chenango Canal:. Canal Society of NYS, www.canalsnys.org. Norwich, NY; <mbeilman at twcny dot rr dot com>.

Sat, April 25 – Middlesex Canal Association Spring Canal Walk, Winchester/Medford. Info: Robert Winters (robert@middlesexcanal.org, 617-661-9230) or Roger Hagopian (781-861-7868). Meet at 1:30pm at the Sandy Beach parking lot off the Mystic Valley Parkway by the Upper Mystic Lake in Winchester. Follow the route of the Middlesex Canal and see the aqueduct and mooring basin, segments of the canal bed and berm visible off the parkway, and the stone wall of the Brooks estate.

Sun, May 3 – Annual Meeting of the MCA, at the Middlesex Canal Museum, 71 Faulkner Street in North Billerica. Dave Barber, Professional Engineer, President of the American Canal Society and former director of the MCA, will talk about "Restorable Canals". Tom Raphael, Director of the Middlesex Canal Commission will also discuss efforts to preserve and transform segments of the Middlesex Canal. See www.middlesexcanal.org for changes and updates.

May 9 – Hands Along the D&R Canal for its 175th anniversary; 10am; <handsalongthecanal2009 at yahoo dot com>; 732-340-1411; pick a spot and celebrate the canal’s anniversary.

May 9 – Spring canoe trip through the historic Santee Canal. Learn about the plants and animals in the swamp. 1pm-3pm; $15; pre-register by May 13th; meet at the Interpretive Center. Contact: Brad Sale, Old Santee Canal Park, 900 Stony Landing Road, Moncks Corner, SC 29461; 843-899-5200; <parkinfo at santeecooper dot com>; www.oldsanteecanalpark.org.

May 16 – Canal Authors Extravaganza to celebrate the 175th

anniversary of the opening of the D&R Canal; Griggstown, NJ. For details,

contact Linda Barth at 908-722-7428 or <barths at att dot net>.

May 16-17 – Two one-day canoe trips on the Monocacy River. Bill Burton,

703-801-0963; <billburton at earthlink dot net>.

June 7 – Garden Party at the Port Mercer Canal House & Canoe the Canal Day on Lawrence (NJ) Canal Day. Boating on the canal followed by ice cream, music and tours at the historic Port Mercer Canal House. Call 609-844-7067 to reserve a canoe through the township and join other paddlers between 1-4.

June 27 – Waterloo Canal Day, Waterloo Village on the Morris Canal, Byram, NJ; Canal Society of New Jersey, 11-4. Free admission and boat ride. Food, sales items. Museum open. 908-722-9556. www.canalsocietynj.org.

June 27-28 – Heritage Tour Days, Monocacy Aqueduct, C&O Canal.

June 28-29 – Two-day Mississippi River cruise – a fundraiser for the Canal Society of Indiana. Interested? Contact Bob and Carolyn Schmidt, 260-432-0279; <indcanal at aol dot com>.

June 28-27 – Schuylkill Canal Day; 9-4 at Lock 60. A day of family fun with much excitement. 610-917-0021; <info at schuylkillcanal dot com>.

August 22 – Wharton (NJ) Canal Day. Boat rides on the Morris Canal. Boat rides, canal lecture, vendors, food. 908-722-9556; www.canalsocietynj.org.

August 30 – D&R Canal’s 175th anniversary picnic at Prallsville Mills, near Stockton, New Jersey; 609-397-3586.

September 12-13 – South Bound Brook (NJ) Canal Days on the D&R Canal. Boat rides, lectures, Abe Lincoln, and much more. www.staatshouse.org; 732-469-5836; <info at staatshouse dot org>.

September 23-25 – World Canals Conference, Belgrade, Serbia. Pre-conference trip, Sept 21-22; post-conference trip, Sept. 26-27.Contact: www.worldcanalsconference.org.

PROJECT UPDATE, MIDDLESEX CANAL COMMISSION

by Tom Raphael, Chairman, MCC

The Easements for the Concord River Mill Pond/ Canal Park Project have been approved and the design drawings have been submitted to the Massachusetts Highway Department for preliminary review. The “Notice of Intent” for Conservation Commission approval is just about ready. There are a few last minute clearances with the historical societies, commissions and abutters. We hope we can now move ahead through the processes to make this project a reality.

LOAMMI BALDWIN’S 1795 PROGRESS REPORT

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

by David Dettinger

This paper was initially presented by the author at the Boott Mill Auditorium on November 1, 1995 as part of the third annual event in celebrating the Bicentennial Decade of the Middlesex Canal. It is an imagined report supposedly given by Loammi Baldwin, Superintendent of Construction, to the directors and shareholders of the Middlesex Canal Company.

Permit me to preface my report on canal construction during 1795 by acknowledging the active support given me, as Superintendent of Middlesex Canal Construction, by your Board of Directors. Not only have they provided clear guidance for our work, but they have directly dealt with practical matters, including locating resources, arranging legal matters, and even participating in the exploration and surveying of routes.

At the outset, let me recall for you several significant actions taken by the Board prior to the start of work. The first was the decision, first proposed in 1793, to extend the Canal to Charlestown. rather than terminating at the Mystic River in Medford, as prescribed in the original Act of the General Court of Massachusetts. This extension, while adding to the overall labor and cost, had obvious merit. The Mystic River is tidal at Medford; this not only introduces the delay of tidal ebb and flow but, more importantly, it requires that cargo be reloaded into lighters for the trip into Boston Harbor. The new plan will carry the Canal to the Charleston millpond directly opposite Boston. This decision was confirmed in February 1795 by an Act of the legislature.

A second decision was made in 1794, regarding the general route of the Canal. As you can see from the chart, the Canal crosses the Concord River at North Billerica, where a mill dam is located. This dam is eight feet high at its center and 150 feet long; it was built to operate a grist mill, as it still does. The Canal Company has taken over this whole area, and is required to operate the mill. This is an extra burden for me, and one I did not anticipate. North from this dam the route is straightforward, heading directly for the Merrimack River at a point in Chelmsford well above the Pawtucket Falls.

South from the dam two route options presented themselves: an eastern route would pass through Reading, the western through Woburn. The eastern route was rejected for two reasons: first it was slightly longer and involved more construction; second, the residents of Reading and Stoneham were generally opposed to the Canal, believing it would spawn manufacturing companies with all the accompanying ills that had plagued such growth in England. They preferred to retain the quiet pastoral surroundings to which they are now accustomed. In contrast, Woburn welcomed the western route.

Before I recount the third decision, let me interject an important event, that in July 1794 we were able to secure the services of Mr. William Weston, a British engineer who had been brought to America to advise on the construction of several canals in Pennsylvania. I cannot resist telling you the ruse we used to overcome his reluctance to making the journey to Boston. Discovering that his wife had a wish to observe the quality of social life in Boston, we were able to get her to persuade him to make the trip to consult with us.

Weston sent along a most valuable instrument, called a “Y-level”, for accurately determining elevations along a path. The instrument consists of a telescope with an integral spirit level. This is mounted in a Y-shaped frame to which are fitted four adjusting screws and a base. The instrument base is attached to a small table supported by a tripod. The adjusting screws and spirit level are used to level the instrument in two dimensions, thereby creating a perfectly level horizontal reference plane. A surveyor then uses the telescope to view markings on a graduated staff at a distant point, previously fixed by range and bearing measurements to accurately determine changes in elevation. If I am correct, ours is the second use in America of this splendid instrument, the first being in Pennsylvania.

With the help of this instrument we were at last able to resolve an uncertainty which arose from our “ocular” survey in 1793. The issue was whether the level of Concord River water at the Billerica dam was higher or lower than that of the Merrimack River above the Pawtucket Falls. Our new measurement showed that the level at the dam was higher by about 25 feet. This means that the Concord River mill pond will become the source of water for the entire Canal, both north and south. Incidentally, we are obligated to return this particular instrument to Mr. Weston, and so our President, Mr. James Sullivan placed an order for two similar “Y-levels” from an instrument maker on Fleet Street in London. These arrived late in 1794 and are now in constant use.

This information entered into a third decision by the Board of Directors in September 1794, namely, to begin construction on the segment between the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Several factors combined to recommend this approach: 1) the distance was about six miles, less than a quarter of the total length of the Canal, 2) the route was almost level requiring only a guard lock at the Concord end to protect against flooding and a flight of three locks at the Merrimack end to accommodate the 25 foot change of elevation, 3) our construction procedures could be developed and progress could be demonstrated fairly quickly to boost confidence in the venture, and 4) traffic could soon begin to ply between the Merrimack Valley and the Concord Valley, generating a little income from tolls.

Accordingly, purchase of land along the route began at once. Here we encountered few obstacles. For one thing, the land is largely unused in this area. Furthermore, the exact location of the Canal was not yet set and presumably could be adjusted to some extent. The offer of immediate payment upon staking the route seemed irresistible. Too, it was recognized that our venture was backed by the power of eminent domain, if needed. Our typical payment averages $25 per acre. However, I am pleased to report that some landowners are attracted by the novelty of being involved in this exciting new venture, while others imagine that a location on the Canal may enhance the value of their property. Considerations such as these have prompted a few to make an outright gift of land to the Canal.

With these actions behind us we set about refining the survey and staking the route. The instrument previously mentioned was invaluable in this work. By the way, my sons assisted in this work, Cyrus carrying the staff and Benjamin handling the chaise, horse, and baggage. We began to lay out the stakes in Billerica on September 17, 1794. Actual digging commenced on September 10, at which time the Directors and myself performed a ground-breaking ceremony on the bank of the mill pond.

For the most part digging is being done by the local landowners. Mostly farmers, they are often able to find time away from their other chores. We are prepared to supply teams of our own or to arrange contracts for digging whole segments where conditions require it. For any and all of these cases we have laid in a supply of shovels, wheelbarrows, etc., as I shall describe later on. The best shovels, by the way, are of English manufacture, the local variety being heavy, and irregular. For your information, the number of workmen of all skills on our pay-rolls in 1795 totals 102. Many of these have been recruited through advertisements in the Village Messenger of Amherst and in the Boston papers.

You may be interested to learn that our President, James Sullivan, has suggested an ingenious way to reduce the labor of shoveling. He has invented a special cart, which can be backed towards a wall of dirt. By digging out at the bottom and shoving the cart underneath, the dirt above can be loosened to drop directly onto the bed without shoveling. The idea has merit, though I believe it will be advisable to modify his design somewhat. This I shall do over the winter, so that we can employ his carts next year. What he has envisioned is in fact a sort of dump wagon. I cite this as an example of the close constant attention given to this venture by our Directors, and their ingenuity in attacking our needs.

Almost immediately we encountered our first major obstacle, a rock formation which required blasting and drawing stones from the ledge. We used the best foreign powder available; nevertheless, a premature explosion occurred and four workmen were injured. We shall use utmost caution to avoid a recurrence. There is no question that we shall encounter other rock formations elsewhere in the canal.

Removing large stones is onerous task. After pulling them up from the bed of the Canal with block and tackle, we load them onto stone drags –these we have had made by a contractor from white oak for $2 each – and dragging them away. When wagons are used, we lay a double line of planks held in place by cross braces to form a railway over rough ground. Similarly, we lay a single line of planks for wheelbarrows.

Clearing stumps is a continual impediment. We have devised a triangular frame, movable on a wheeled base, which provides a mechanical advantage so that a team of oxen can pull a stump once it has been partially freed at the surface.

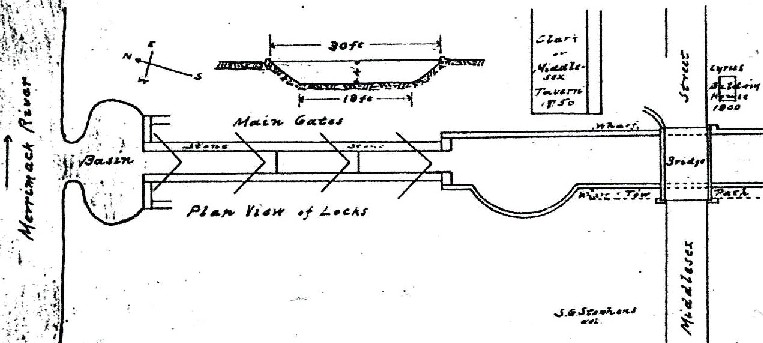

With regard to the locks at the Merrimack River, a committee met in September to set up a contract to lay stones for the lock. An agreement was reached with Bemis and Stearns, Stone Layers. This contract is not a simple document. It sets out specific tasks and responsibilities for both parties; I shall not go into the details. The dimensions of the locks are to be governed by sketches such as these below, the first an elevation view of the three locks and the second a plan view.

Lock Plans, from MCC Corporate Records

Planning for the construction of these locks (and others) confronted us with two problems: the first arises as our excavation approaches the river. Water is bound to seep in and later to rush into the canal bed. The same occurs in swampy areas. We find it necessary to build and use pumps to permit digging to continue. These pumps are simple contrivances made of bored logs fitted with plungers flanged with sole leather. On occasion it has been necessary to operate these pumps continually. Incidentally, in making and using these pumps we have exchanged valuable information with the Aqueduct Corporation of Boston, which was organized by Mr. Sullivan to pipe water to Boston from Jamaica Pond. We have even borrowed pump tapers from them on occasion.

The second problem relates to the cement to be used in the stone locks. Because of the constant presence of water it is essential that the cement, called hydraulic cement, harden under water. We learned that such cement can be made by mixing a volcanic substance from Italy, called pozzuolana, with lime and sand. We attempted to obtain some, but this effort did not bear fruit. More recently we have heard of a substance, Dutch Trass, which comes from an island in the Dutch West Indies. This appears to be more effective and less expensive. We have already engaged the sloop Industry to proceed to the island of St. Eustatia to procure a substantial quantity of this material as cheaply as possible. The trip being a long one, we cannot expect the trass to be delivered until next year. As in other matters, we seem to pioneering in this construction technique.

Two aqueducts will be needed in this segment of the Canal, one over Black Brook and another over River Meadow Brook. We have not begun work on either of these at this time. I recommend that we build masonry piers with a cradle at the top to hold wooden beams that form a water channel. If they were carefully fitted the natural expansion of the beams should seal the bed. These beams could be removed in the Fall and replaced in the Spring if deterioration makes it necessary.

In addition to these two aqueducts it will be necessary to build three culverts to carry the Canal over smaller brooks. We began one of these on October 6, using brick construction. The next day we laid out the three locks into the Merrimack. Two weeks later the first load of stone was boated down river from Tyngsborough; other loads will follow in plenty of time for stone laying.

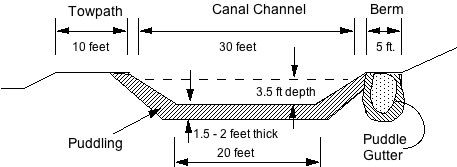

Let me now go back to emphasize an important feature of the canal bed itself. Naturally, it is expected to hold water. In areas where the ground is already firm this not a problem. However, in others, such as swampy or sandy areas or where embankments must be raised, leakage or washouts can be a serious matter. The answer to this danger lies in a technique called "puddling." Puddling is the process of lining the canal bed with clay which is impervious to water. The clay must first be evenly mixed with water to the proper consistency and then applied in layers to a depth of two or three feet.

As shown below, the dimensions of the channel (or prism as it is sometimes called) are 30 feet at water level, 20 feet at the bottom, and 3-1/2 feet deep. These dimensions apply everywhere except: where a rock ledge defies full enlargement ; under bridges; and through aqueducts and locks. Notice the extra excavation required to accommodate puddling.

Cross section of the Canal, showing the location and thickness

of the impervious clay layer, also an example of a Puddle Gutter

At the right is shown an additional need for puddling. Called puddle gutters, these waterproof bases are required under any embankment above swampy ground to resist erosion. After removing any stumps and uncovering hollows these puddle gutters must be made wide and deep enough to form a foundation upon which solid earth can be filled and tamped to make a secure towpath or berm. It will be obvious that the requirement for puddling greatly increases the amount of excavating; staking must take this into account, and digging assigned accordingly.

Perhaps this is as good a time as any to point out the magnitude of the venture upon which we are engaged. If one takes the nominal dimension of the Canal bed (or prism), one finds the cross section to constitute an area of about 88 square feet. The total length of the segment currently being dug is six miles, a little over 30,000 feet. Multiplying these values tells us that around 3 million feet of earth must be moved, all by hand. This, however, is only a fraction of the labor involved. All this dirt must be moved, some of it to form the towpath and berm, but more carted away to serve as fill in low-lying stretches. I have already mentioned pulling stumps, removing large stones, blasting ledge, puddling the canal bed and constructing puddle gutters, and pumping out water as necessary. Add to this the building of locks, aqueducts, culverts, bridges, etc., as well as the surveying, planning, and staking that precedes each step, and one begins to appreciate the huge amount of labor demanded. On top of this, remind yourself that we are describing less than one quarter of the entire Canal, and the easiest part at that.

To conclude this first portion of my report, let me remark that most of the activities I have described come to a virtual halt with the advent of winter. We were stopped in November of 1794; work began again in March. This is a pattern we must accept, so we use the winter months for other chores, such as making new tools and repairing old ones, cutting timbers for lock gates, aqueducts, bridges and the like, and doing other indoor work.

Next I shall address the facilities which the Canal Company is providing. First of all, we purchased a sawmill on the property acquired from Thomas Richardson in Billerica for $6265. This we use in cutting timbers and various wooden parts. We built our first blacksmith shop here, which is heavily used in making new parts, and repairing tools broken in use. We have recently added a second blacksmith shop at a different location.

We have a master carpenter at work making wheelbarrows and tool handles. Incidentally, I requested Mr. Weston to send us a proper wheelbarrow as a sample, but none came. Consequently, I wrote requesting dimensions and advice regarding iron parts and wooden wheels; this information is being used by the carpenter.

The list of tools and equipment owned and supplied by the Company is extensive. It begins with wheelbarrows, shovels, spades, and other digging tools, then moves to the blacksmith shop with its accouterments and its stock of material. Next comes equipment for blasting and stone work. Also, included are four oxen and yokes, one cart – we are building more – eight boats and another building. Other items include gunpowder, 20,000 bricks, carpenter’s tools, two barracks, field beds and bedding, etc.

My final topic is the matter of costs. I shall not address the overall topic of financing in this report, leaving it to others to report on the sale of shares and the levying of assessments, a process that is bound to continue, alas. I wish only to record the names of a few of our more prominent shareholders to remind you of the solid support this venture enjoys: John Hancock (now deceased), John Quincy Adams, Christopher Gore, Andrew Craigie, and, of course, our President, James Sullivan. We take great care to account for all expenditures. All amounts are always paid at the accepted exchange rates; this is currently running at $4.44 dollars per pound sterling.

Earlier I mentioned a triangular frame for removing stumps. Equipment such as this is in constant need of repair. As an example of this work, the original pulley blocks wore down rapidly under the stress of heavy use, and were replaced with sturdier pulleys made of lignum vitae wood.

The cost item of most obvious concern is the pay of workmen for the digging itself. The rate was at the level of $7 per month at the time work began in 1794, but the demand for workmen has inevitably driven up the rate, and we are now faced with paying $8 per month. This rate covers an average 26-day month, that is, 6 days per week dawn to dusk. Brief pauses are permitted for breakfast and dinner, but only long enough to consume the meals. Supper follows after sundown. An exception is permitted in midsummer, when the men are allowed and hour and a half to rest; in this case they are expected to work until 20 minutes after sunset to make up the lost time.

Pay is higher for men with special skills, such as stone workers, carpenters, blacksmiths, etc. Their pay may run as high as $13 per month. Pay is higher for boatmen, since they are allotted $1 per day, but are expected to find themselves food and drink. We are faced with additional cost when the work is done by other than local landowners. We have had to build barracks for workmen and to provide meals for them. Alternatively, men may seek boarding houses nearby. In this latter case we make a standard payment of $2 per week for room and board. As you can see, this roughly doubles the cost per workman.

My final example has an unusual feature regarding payment. Recall that the Canal Company purchased the farm of Thomas Richardson in Billerica. (It was he who presided at our ground-breaking celebration in 1794.) We arranged to rent the farm back to him during the year May 1794 to May 1795 for $282, and he accepted this rental as a partial payment against his bill for boarding workmen.

I shall not try to summarize our expenditures to this time, since construction is merely in its beginning stages and we are learning as we go. I can tell you that we have been able to let water into the Canal from the Concord River as far as Timothy Manning’s farm in Billerica and find it holding reasonably well. In another year we hope to have completed the segment to the Merrimack River. That will truly be cause for celebration!

As is evident, constructing the Canal is an immense undertaking, one for which there is little experience in the United States of America. We are constantly devising and experimenting with new techniques; some fail, nevertheless we persevere. We are determined to bring this venture to a successful conclusion within the ten years allotted. I ask for your confidence and your support.

LETTERS FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE BOSTON DAILY ADVERTISER (# 2)

This is the second of five letters. The first letter was published in the autumn 2008 issue of Towpath Topics. It was transcribed by Howard Winkler from an electronic facsimile found at the Tisch Library, Tufts University. Neither spelling nor punctuation were changed.

LETTERS, First Published in the Boston Daily Advertiser, NO. II (1818), in Answer to Certain Inquiries, Relative to the MIDDLESEX CANAL by John L. Sullivan, Agent of the Corporation.

The outline given of the origin and object of the Middlesex Canal will I hope have removed all doubt, that the intelligent men who engaged in its construction, had well considered its resources and effects:--and the inquiry why it has not yet succeeded according to the wishes of the proprietors, becomes perhaps peculiarly interesting at this time, when the policy of internal improvements of this nature, is assuming an importance that entitles them to the patronage of several of the state governments, and even to the attention of Congress.

It may therefore be due to the public, to discriminate, in this example, between the causes of disappointment inherent in an enterprise, and those which are accidental and temporary; and although I could not have offered this exposition of facts, it will now be very cheerfully given in the hope of its usefulness.

At the period when the water of Concord river first flowed to Boston harbor through the canal, the proprietors were numerous; but a few held a large number of shares. — Misfortunes from a remote source overtaking some of them, impediments to a vigorous prosecution of the work sprung up — and the expenditure already great, though differing from the original calculation, but in proportion to the variation and extension of the plan, seemed perhaps disproportionate to the product; and consequently discouraging to those who had not seen its object from the first, or who had lost sight of it — and to those also who had succeeded by inheritance or purchase, to original proprietors. Assessments ceased probably, from the hope, that, the income would early supply funds sufficient to pay off their debts, and complete the work. Thus a misplaced tenderness towards those on whom further assessments would have sat heavy, first occasioned, in my opinion, a premature opening of the Canal for business, before proper arrangements could be made — before the banks were well consolidated — before it was capable of giving requisite facility to business, and security to property transported, in a manner essential to its reputation and increasing usefulness. Breaches in the banks repeatedly took place for the want of proper care and attention. The leakage was excessive, and occasioned litigious claims for damages — property on reaching the tide was scattered and lost — the mode of collecting the toll was ineffectual.

The proprietors must therefore take some blame to themselves, for these troubles were not incident to the nature of the undertaking. But there were greater obstacles to the immediate success, not within their control; of which perhaps they were not generally sensible, and which many may have hoped and expected to see overcome, by efforts correspondent to their own, in a sister state, where the benefits of the enterprise were to be most extensively felt.

Their object was indeed to connect Merrimack river with our harbour, but it could not have escaped the discernment of the projectors of the canal, that the Merrimack was obstructed, by several considerable falls; and tho’ the periodical rafting of lumber and timber might be expected to afford a considerable revenue, yet the principal benefits to be reciprocated between the town and country, could not be attained without making it navigable for boats. A thorough examination of its bed, was probably never made until at a subsequent period, as the opinion had some how become prevalent, that all would be accomplished in the canal around Amoskeig falls, projected and owned by Judge Blodget.

He executed this work in his own way, and however ingenious and enterprising himself, the event proved that he would have done better, with the assistance of an experienced engineer. For excepting some portion of a dam, and some passages through ledges, nothing now remains of what cost him his estate.

Possessed of the key of the river, and the control of his incorporation, there was no mode of assisting him in this undertaking but by the loan of money for four-fifths of his shares, were already pledged to a bank for security of a heavy debt.

His resources being exhausted, a lottery was granted him by New-Hampshire, and the sale of tickets allowed him in this commonwealth, on condition that the money raised, should be applied by Col. Baldwin. And twelve thousand dollars thus derived and employed, built the locks at the lower extremity of that canal, and excavated the trunk of it for above 2000 feet.

The directors of Middlesex canal appear thus to have been attentive to the river, as far as was then in their power, aware that unless Amoskeig falls were passable, there could scarcely be much business even from rafting. And that until then, nothing could be done to the other falls both above and below this place, which presented insuperable barriers to the passage of boats.

These places I shall have occasion to mention subsequently.

Thus from 1803 to 1807, the canal was struggling with the troubles of its own incompleteness — with the damage done by the inexpertness, and heedlessness of the conductors of rafts — with the difficulty of managing so novel and great a machine, without experience — with the impracticability of enforcing the collection when it was deemed important to conciliate the people — with the improbability of being soon able to open the river, and (from all these causes) — with the discredit, which had driven this great property to the verge of abandonment.

Under these discouragements it was rather to be expected that every species of dilapidation would take place; especially as the system of management was radically a bad one. The care divided between four gentlemen, each competent in his department — no one having that responsibility and control requisite to supply the place of a board of directors, which, though it might wisely frame bye laws and regulations, could have no efficiency in the execution of them. A superintendent resided in the country, near the canal, but his authority was limited to certain objects. Experience by this time had taught the necessity of some new system that should supply by its energy, the difficulties of local extent, and the impossibility of the requisite attention on the part of the board, assembling at home, and unremunerated (as they ever have been) for services.

Being myself a proprietor, and having then recently returned from abroad, where curiosity had led to an observation of some of the principal Canals — my name was added to those of several gentlemen to form a committee on the whole state of the concern. They reported amongst other things a union of the several offices in an agent to be invested with much discretionary authority — but whose duties would lead him to an intimate acquaintance with the details of the whole business.

Public notice was given of the creation of this office, and applications for it invited. — No one offering to the acceptance of the board, I was requested by some of the directors to offer to take it for a season.

Egotism is so unacceptable and inexcusable on most occasions, that my apology must be found in the relation I have so long sustained with the proprietors whose disappointment at present it has devolved on me to account for, and the necessity of these preliminary remarks to a complete understanding on the subject.

I accepted the charge accordingly, and found it necessary to devote much time, and labour to every branch of the business; and to account for the expenditure of the income, it is necessary to mention that the Canal was in great disorder, and wanted much, immediate repair, and alterations; tenements for the lock tenders were to be erected, wharves, booms, improvements of various kinds to be constructed, a system of business, collection and management to be carried into effect; suitable men to be procured and instructed, some lawsuits, controversies claims and debts were to be settled and collected. A very incessant inspection and superintendence of the works, as might have been expected, was necessary. But this occupation did not prevent some considerable degree of inquiry into the state of Merrimack river, to the head of which in the course of the summer I had made some observations, and saw with surprise and regret, how much remained to be done, and the improbability of its accomplishment — for I was till then unacquainted as most of the proprietors were with its actual obstructions.

It was not navigable for boats of any considerable burden more than four miles from the Canal: boats of a small and light construction could with great difficulty and hazard pass Wicasee fall and several others with greater danger to about 20 miles. Below Amoskeig there were eight places requiring locks; above, there were two considerable falls, 18 to 25 feet perpendicular hight besides a number of impassible places requiring expensive channels, in order to reach Concord.

Blodget’s Canal had by this period become impassible from decay, and the property involved in various disputes, even about the ground it occupied.

It was evident that the Middlesex Canal could never become profitable till all these obstacles were removed, and its perishable parts almost renovated; and that too with the circumstance in view that the income of 1808 had been insufficient to the ordinary expenses and repairs.

These facts being made known by conversations and reports, the alternative presented itself to the proprietors of persevering to the accomplishment of the original design, or of relinquishing it forever.

A question of this importance was not to be acted upon without precaution. A committee was sent up the Merrimack, and the proprietors after much deliberation, adverting to the original intention, its motives and its basis, and unwilling to abandon a property of this magnitude in its incomplete and untested state — still convinced that the project was naturally a good and useful one, and still actuated by that honourable pride and spirit which had sustained many of the gentlemen concerned, through the fatigues and vexations of a ten-year’s effort — the proprietors I believe unanimously determined to persevere.

The attention I had given to the concern, though not intended to occupy my whole time, had much interfered with my business — and I declined any further agency. But the knowledge gained of its interests seemed to make it desirable to the Directors that I should continue. Induced by some interest of my own and by that of my family, with some other motive, I devoted myself to this pursuit, considered of public importance at that time, as perhaps it will be hereafter.

The Corporation could not afford then to allow the compensation I thought it reasonable to ask; but the Directors stipulated that in addition to the salary of the office, I should have a commission on the gross income, warranting a certain amount — and thus engaging my interest in the course of measures which could alone attain their object — I was led to invest property, to devise means to produce business, and especially to acquire the requisite knowledge of civil engineering to construct the canal around the falls, and other works on the water, to open its navigation. This arrangement, since annually confirmed, is mentioned in its order merely for the information of the proprietor who instituted the inquiry, as well as for others, who may have supposed the expense of management to be subsequently explained, and of which my commission is a part disproportionate to its object.

As early as convenient, I shall give some account of our subsequent proceedings, and of the auxiliary canals.

JNO. L. SULLIVAN

JAMES

SULLIVAN’S BIRTHPLACE

JAMES

SULLIVAN’S BIRTHPLACE

by Howard Winkler

James Sullivan, the creative force behind the construction of the Middlesex Canal, was born April 22, 1744 in what is now Berwick in the State of Maine. Berwick is located in very southern Maine; its western boundary, the Salmon Falls River, is the state line with New Hampshire. At that time, his birthplace was in the District of Maine, and part of Massachusetts. He was the son of John Sullivan and Margery Brown. (A short biography of Sullivan taken from the Dictionary of American Biography, can be found in the October 2006 issue of Towpath Topics.)

The farmhouse is no longer standing, but there is an historic marker at Pine Hill Road and Sullivan Street which indicates its site.

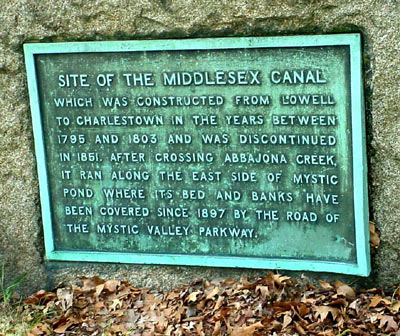

A close up of the marker follows.

The inscription on the marker states:

ON THIS SITE WERE BORN

CAPT. DANIEL SULLIVAN MAJ. GEN. JOHN SULLIVAN

GOV. JAMES SULLIVAN CAPT. EBENEZER SULLIVAN

REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOTS

CHILDREN OF

MASTER JOHN AND MARGERY SULLIVAN

ERECTED BY

JOHN A. LOGAN, JR. W. R. C. NO. 76

In addition to James Sullivan, the Dictionary includes Major General John Sullivan who led what become to be known as the Sullivan Expedition, a punitive military action against the Iroquois Indians on the New York frontier. Later, he was elected chief executive of New Hampshire.

I wondered about John A. Logan, Jr. W. R. C. No. 76. From an Internet search, I found that John A. Logan, Jr. (1865 – 1899) was a United States Army Officer posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during the Philippine–American War. His father, Major General John A. Logan, was also cited in the Dictionary. Among Logan’s many accomplishments, he was also an organizer of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War, Union veterans, association. From the W. R. C. Internet site, the "National Woman’s Relief Corps, Auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic, Inc., is a patriotic organization whose express purpose is to perpetuate the memory of the Grand Army of the Republic." Their site provides an email address, and I tried to make contact, to learn the connection between the Sullivans and the W. R. C., but without success, so far.

Lastly, I found a biography of James Sullivan published in 1859, and copied a few paragraphs that follow.

JAMES, the fourth son of Master Sullivan, was born on the farm at Berwick on the twenty-second of April, A. D. 1744. The cellar of the house occupied by his parents is easily distinguished by some portions of its walls still remaining in a field near Salmon Falls River, and within half a mile of the Great Falls village. The barn, which served to store away their harvests for the long winters of our New England climate, has only quite recently been destroyed by fire. Nearby, but separated from the site of the old dwelling by a public road, laid out in comparatively modern times across the farm, is the ancient cemetery, where Master Sullivan and Margery his wife, when their long-protracted lives were over, were laid to their last repose, amid the scenes of their humble labors, and of the pleasures and various vicissitudes of more than half a century.

Few country places in New England possess greater variety of agreeable rural scenery than old Berwick; and the narrow, rocky defile, through which rushes the impetuous stream constituting its western boundary, and here separating the States of Maine and New Hampshire, has long been celebrated for its wild and picturesque beauty. Within a limit of four miles the Salmon Falls River, called by the Indians the Quampegan, wearing its way through walls of granite, which rise on either side in precipices or steep slopes clothed with vegetation, descends in rapid or cataract more than two hundred feet, before, making its last plunge at the village of South Berwick, it moves on, but with more quiet now, towards the ocean. The vigorous rush of its waters has been long since brought into subjection by human power and contrivance, and applied to the purposes of utility; but a century ago, when the subject of our narrative wandered yet a lad about its shores, the stream poured through the dark primeval forest, undisturbed except by an occasional saw-mill, which, to his youthful taste, lent but another charm to the scene.

Berwick was then a frontier settlement; and not long before, one of its inhabitants, speaking of his dwelling, says there was no other house occupied by any white man between his own and Canada. The population, however, was gradually increasing, and the exasperation of the Indian tribes, as they marked the steady encroachment of the stranger on their hunting-grounds and most favored fisheries, was often manifested in stealthy attacks on some unguarded settlement, and by midnight massacre. Occasional retaliation served but to deepen further the spirit of resentment, and the annals of the period abound in revolting details of savage barbarity. Many a hearth was rendered desolate by the mysterious disappearance of child or parent, carried away by Indian war-parties to their distant villages. The inventive cruelty of our New England races quite equaled that recorded of any other people, and the captive rarely survived the agonies they took pleasure in inflicting amidst the brutalities of their fiendish festivals.

from: Life of James Sullivan, Vol. I, pp.17 and 18, Thomas C. Amory, 1859.

No comment on the political incorrectness in 21st century America of the last paragraph.

I want to thank Wendy Pirsig, Archivist, Old Berwick Historical Society in South Berwick, Maine for providing me with James Sullivan’s birthplace information and photos. - Howard Winkler

THE BALDWIN APPLE

The following are excerpts from an article by Marshall Symmes quoting Charles Brooks in the Winchester Records for July 1, 1885.

“The first tree producing this delicious fruit grew on the farm of Ebenezer Brooks. who bought the farm in 1715. It was afterward owned by his son Caleb, the father of Governor Brooks. The tree was about 600 feet south of the Old Black Horse Tavern in Winchester and three rods east of Main Street.”

“At the request of Governor Brooks I made a visit to that tree in 1813 and climbed it. It was as very cry old and partly decayed but bore fruit abundantly. Around its trunk woodpeckers had drilled as many as six circles of holes, not larger than a pea, and from this most visible peculiarity the apples were called woodpecker apples By degrees their name was shortened to peckers and during my youth they were seldom called by any other name.”

“How they came by their present appellation is this: Young Baldwin of Woburn was an intimate friend of young Thompson. One day as they were passing by the woodpecker tree, they stopped to contemplate the tempting red cheeks on those loaded boughs and the result of such contemplations was the usual one; they took and tasted. Sudden and great surprise was the consequence. They instantly exclaimed to each other that it was the finest apple they had ever or tasted.”

“Some years after this, Colonel Baldwin took several scions to a public nursery and from this circumstance they named the apple after him. In the gale of 1815, this parent tree fell: but few parents have left behind so many flourishing and beloved children.”

A NEW BALDWIN APPLE ORCHARD FOR THE SANBORN HOUSE

by Sue Clark

The Girl Scouts of Troop 1474-5 approached the Society this past spring with a suggestion to reestablish an apple orchard on the grounds of the Sanborn House as their Bronze Award project. The Bronze Award is the highest honor for a Junior Girl Scout; five girls from the troop will earn their award by researching. planning, planting and caring for the orchard. Peter Wild, a Certified Arborist and owner of Boston Tree Preservation, enthusiastically accepted a request to be their advisor.

The troop began their project by taking cuttings from an historic Baldwin apple tree on the property of the Wyman family home on Everell Rd. The tree is believed to be the oldest Baldwin apple tree in Winchester. well over one hundred years. While educational the scion cuttings were not successful. Mr. Wild graciously donated three young ‘Golden Delicious’ trees to get the orchard started. They were planted in June and are thriving in their new home just to the left of the Sanborn House. The ‘Golden Delicious’ variety was chosen for it’s resistance to disease and insect damage The new trees join an existing old Baldwin apple tree already on the property. The Scouts hope to acquire two more young Baldwin apple trees in the spring to finish off the orchard.

Members of the Downes family who owned and lived in the Sanborn House from 1920s to the 1940s remembered that a Baldwin apple orchard once stood on the current site of the Ambrose Elementary school. The family shares fond memories of their childhood when fall meant picking apples, placing them in barrels in the basement, and bringing apples up in the wine lift (elevator) in the Oak Room of the House after dinner each night.

The Winchester Historical Society would like to thank and congratulate Susan Wilson, Rachel Diamond, Kate Clark, Chloe McCarthy, and Elma Joseph for all of their hard work on this project as well as their co-troop leaders. Sue Clark and Ellen Wilson.

The Baldwin apple orchard will officially be dedicated to the memory of Jon Fischbach who served the town of Winchester through his tireless efforts to improve the environment and was an active supporter of the Girl Scouts.

WIFE-SWAPPING ON THE OHIO & ERIE

This story comes from Canal Fulton, along the Ohio and Erie Canal. I know of no comparable story from the Middlesex (but would like to hear a few). Ed.

Our old friend and canaler, Dillow Robinson, told this story and those who know him can vouch for the truthfulness of it.

Traffic on the canal was just about finished. Income was practically nothing and soon all this canaler friend of Dillow’s had left in the world was his boat, his wife, and a team of mules. Things didn’t get any better, and there seemed to be only one way for them to survive the winter: he had to sell the team.

It was a desperate solution because a canaler without a team couldn’t operate. Perhaps a part-time job would crop up before the boating season started, and he could earn enough to purchase a new team.

But the part-time job didn’t materialize, and this time there didn’t seem to be any solution. Then, a tiny glint of hope beamed from far over the horizon; a Cleveland firm had a whole boatload of paint for a client in Canal Dover.

The old canaler was asked if he wanted the job. Did he? He’d get cash-money to haul this load, and Canal Dover was only a short distance away. He could buy a boatload of coal there that could be sold at the paper mill in Akron. If not, Cleveland’s lake steamers could almost certainly use the coal. Then, even if a return cargo couldn’t be found, there’d still be enough money left to return “light” and pick up more coal.

The big problem was, of course, that with no money, getting a new team was going to be difficult, if not impossible. A quick round of all the obvious places confirmed that opinion. Though many wanted to help, no one could afford to wait until after a few trips to get their money.

One of these folks was Caleb Atwater. He had left the canal a few years before to take up farming and had a spare team of mules; however, he, too, had his problems.

“Sam,” he said. “You know I’d help if I could, but Martha has to go back East for a few weeks to look after her sick mother. I need cash money from selling those mules to hire someone to take care of the house and look after the kids while I’m in the fields all day.”

At that, the gears in old Sam’s head began to grind, and he got a crafty gleam in his eye. “Don’t do anything about the mules till I get back,” he shouted as he ran out the door. “I have to check into something, but I think both our troubles are over.”

Sam rushed home and explained the situation to his wife. “You know, Mary,” he concluded, “It’s not as if house-keeping and kid-watching were strange to you; besides, it’ll only be for a few weeks.”

And that’s how it worked. Mary Arthur became Caleb Atwater’s house-keeper and babysitter, while old Sam got the use of a team of mules free for a time.

Things went well for Sam after that. He grew lucky picking up southbound cargo and was able to buy the team and get Mary “out of hock.” He was also able to set a little aside, and he and Mary got off the canal a few years later.

Of course Sam gained quite a bit of notoriety as the man who swapped his wife for a team of mules. That title didn’t bother Sam much. “Actually,” he’d say, “I was doing her a kindness. She’d tended house and minded kinds all her life, so it was no hardship, but it would have been cruel to expect that good woman to pull a canal boat all by herself.”

Thanks to Terry Woods (past President of the CSO), the Hoosier Packet, and the Canal Fulton.

RAFT LOCK? WHAT’S A RAFT LOCK?

by Bill Gerber

Among the Middlesex Canal Company records there is an early plot plan of North Billerica village, on the west side of the Concord River crossing. Shown in that plan is the guard lock which protected the west branch of the canal whenever the river level was higher than the water level in the canal channel. Also shown is an extra set of miter gates located some distance further west of the lower guard-lock gates. The purpose of these gates has long been a curiosity. Speculation has usually been that they had some sort of flow control function, perhaps to close off the rush of water that would occur in the event the canal was breached somewhere.

But miter gates are an unlikely choice to seal off flow in an early, economically struggling canal. Usually, the function of a stop gate was accomplished with a stack of planks that could be inserted, manually, into grooved anchor stones or timbers on either side of the channel. Mitre gates might well be swept away by a sudden flow, and they would have been functionally superfluous to the guard lock, only a short distance away. So why put miter gates here?

Early in his manuscript, Lewis Lawrence quoted John Langdon

Sullivan’s 1810 report to the Middlesex Canal Proprietors, in which he

accounted for 1809 activities and expenditures. (Appointed in 1808, Sullivan was

“agent” [CEO] for the canal.) He stated:

“… . The item of improvements comprehends a number of objects … Buildings,

Bridges, &c. Of the latter are more particularly the boats, floating bridge

at Concord river, the landing places on the Merrimack, and the raft locks.”

[Italics, mine.]

Sullivan goes on to say:

“The gates to form the Raft Locks I consider an important improvement in its

immediate consequences.”

“From the head of the canal at the Merrimack, to Concord River where the Canal crosses, it is about five miles. Here a large pond is formed [by a dam across the river] to supply the canal with water, both toward the Merrimack, and towards Boston. The difficulty and delay in getting rafts from the first level into the pond, and across it, has always been complained of, and has alone been sufficient often to decide people to go with their rafts to Newburyport. For when they had reached this place, it was necessary to disjoin all the divisions of it [a band of rafts] and push each one [raft] separately against a current into a lock. When it was raised to a level with the pond, they had then to convey it across the pond and lock it down to the level on the eastern side; where, after they had all successively arrived, they were to be reunited [reassembled into a band of multiple rafts].”

“The Raft Locks, which consist of strong gates at a sufficient distance from Concord River on each side, will raise the whole raft [band] to a level with the river or pond; over which it may now be towed by horses or cattle; and by then let down to the next level without any delay, instead of being detained a whole day, and the conductor subjected to expense and trouble.”

In his history of the Middlesex Canal, Christopher Roberts also describes an 1810 (sic)project in which the Guard Locks at the Concord River were lengthened to accommodate “bands” of log rafts.

Ignore, for the moment, that William Weston (the English Canal Engineer who was Loammi Baldwin’s mentor) was horrified that the Middlesex Proprietors would even consider transporting log rafts because of the certainty that they would gouge and scour its banks. Taken together, these observations describe yet another innovative feature unique to the Middlesex Canal.

Following the end of the Revolutionary War, the need for timber and wood products in seacoast towns was a prime motivation for the construction of the Massachusetts and New Hampshire canals. Except for shade and wind-break trees, the population had largely deforested an area as far west as Concord and likely well beyond. Furthermore, Boston merchants were vying for prominence as a major city and the port closest to Europe. Thus, timber and wood products remained important cargos throughout the life of the canal system. (Along the Mystic River alone, well over 400 ocean-going sailing vessels were constructed by Medford shipbuilders during the time the Middlesex Canal operated.)

But, because the Merrimack River was replete with falls and rapids of various heights, lengths and ferocity, logs left to float freely would often be seriously damaged crashing into rocks and boulders while descending the river, and sometimes lost when driven into the river bottom. Because of this great damage potential, it was preferred practice to assemble logs and masts into rafts, often to band multiple rafts together, and to use crews of men to control their passage on the river and canals; that is, to steer the rafts or bands along safe passages and to use canals when necessary to bypass the rapids. However, during freshets (periods of high water on the river, the preferred times for moving logs), some of the lesser canals (e.g., Wicasee, Cromwell’s and the six Union Canals) would be flooded out and the rafts and bands could safely pass over them, thereby avoiding lockage fees. On the Middlesex Canal, an entire band could easily be towed by a few oxen.

Fee avoidance was a popular “game” of the early raftsmen. In an old diary from the Blanchard family of Merrimack, mention is made of “Whitings Rock” (near Cromwell’s Falls). When it was flooded out, “the Newbury pitch was on” and they could avoid all the lockage charges for passage to Newburyport. This may also have been a factor in the decision of whether or not to divert to Boston via the canal.

No doubt there were many variations on how raft building was accomplished. New England’s virgin pine and spruce were light and rode high in the water; but most hardwoods, e.g., oak, floated much deeper. For this reason, the hardwoods were sometimes alternated or interspersed with logs of lighter woods such as pine, poplar or ash. In some cases, logs were fastened, side-by-side with multiple “timber dogs”, i.e., large wrought iron “staples” that fixed one log to the next adjacent log. Another technique, logs were bound together with strong, supple saplings, e.g., oak or hickory, pinned or chained orthogonally to the main raft logs. Most likely there were other variations.

Some sort of shelter was usually constructed on the rafts to

protect the crews and their supplies in inclement weather. To provide a fire for

cooking, for warmth at night, and for drying out water soaked clothing and

bedding, a clay and/or brick hearth would often be assembled on the raft near

the hut.

Fore and aft oars and poles were used to guide the raft down the river. A pair

of pegs (thole pins) at the bow, and another pair at the stern, served as

fulcrums for long sweep oars. Working together, fore and aft sweeps would enable

the raft(s) to be moved sideways, as needed, whenever it (they) entered fast

water. Poles sufficed when the raft or band entered relatively still water, and

to guide the rafts toward or from locks. To avoid damage to locks, rafts and

boats were usually assisted through by local tow animals.

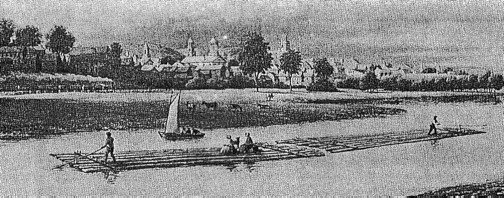

As suggested above, it was not efficient for crews to bring down a single raft. Instead, typically, multiple rafts would be linked together, end to end, into a “band” sometimes consisting of as many as ten rafts. A two-raft “band” is shown in Figure 1, below. By regulation, at least on the Middlesex Canal and probably on the river as well, at least six men were required to maintain control of a ten-raft band; also, on the canal, band lengths were initially limited to 500 feet, later to ten rafts. Somewhat fewer men were permitted to control smaller bands.

Figure 1. Two Raft “Band” on the Merrimack River.

Lithograph, ca 1850 Courtesy of the New

Hampshire Historical Society

But there was an inherent problem with this arrangement. Each time the band arrived at a canal lock, it had to be disassembled so that each raft, or possibly several short rafts, could be locked through independently. Then, once all rafts were through, or as they came through, the band could be reassembled; travel would resume when this operation was completed. This was tedious and time consuming, but it was a necessary fact of life for travel on the river and canals. It was also the reason that, initially, many of those taking timber to market preferred to pass through the Pawtucket Canal and on down the Merrimack River to Newburyport, rather than negotiate the greater number of locks of the Middlesex Canal.

Exacerbating this problem, in the very early years of the Middlesex Canal, the size of the floating towpath at the Concord River Crossing constituted still one more impediment. Here, the tow animals (typically a pair of oxen) were detached and the individual rafts would be locked through from the west branch, “manhandled” across the river, and locked through to the east branch, while the tow animals were led around on a different path to cross the river at a shoal or on the dam.

The Middlesex Canal Proprietors soon realized that they needed to take steps, where possible, to reduce or eliminate impediments to the use of their canal. In 1809, the floating towpath was enlarged so that tow animals could draw their “tow” directly across the river. At about the same time additional gates were constructed in the canal channels, on either side of the river, to functionally extend the length of the guard locks. By this means, these extended locks enabled entire “bands” of log rafts to be raised to river level, towed across the river, and lowered to the level of the east branch, without requiring disassembly.

The west side guard lock described above is shown in an 1829 survey map of the Middlesex Canal. (The upper end of that guard lock can still be seen immediately west of Lund’s Bridge, under the edge of the parking lot at the Talbot Mill. Most of the lock chamber and the lower gates have apparently been covered or otherwise lost to other construction at this mill site.)

Curiously, the extra gates are not shown on the east side of the river. But, in a section of his manuscript describing the structures encountered as one ascends the Middlesex Canal, Lewis Lawrence mentioned a gate across the channel east of Lincoln Lock, the east side guard lock at the same Concord River crossing. He states that it was probably first built in 1809 to form a raft lock; thus its existence is documented elsewhere.

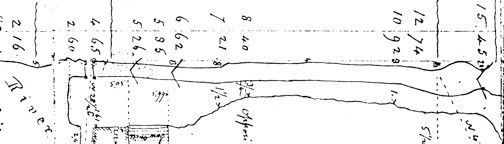

An excerpt from the survey is shown in Figure 2, below. Also shown are the additional miter gates displaced to the west (right) of the guard lock. Since this is a hand-drawn map prepared as part of a survey, each of the mitre-gate pairs bear numbers that relate to compass bearing, linear distance, and elevation. From east to west, the distance numbers are: 5 26 at the upper lock gate, 6 62 at the lower lock gate, and 15 45 at the raft lock gates.

Figure 2. Excerpt, West Side of Concord River Crossing

1829 Survey of Middlesex Canal

These numbers are almost certainly recorded in the measuring system used by surveyors of the time; see the inset. Furthermore, the way they are presented suggests that they most likely refer, respectively, to Chains and Links.

|

To obtain the lock chamber dimensions, we are interested in the difference between pairs of readings, thus (or so it seems reasonable to expect):

Normal Guard Lock Length -- 6 62 less 5 26 - should give - 1 chain and 36 links, and

Raft Lock Length -- 15 45 less 5 26 - should give - 10 chains and 19 links.

In a more familiar measuring system, these dimensions would

be:

Normal Guard Lock Length -- 66 feet (1 chain), plus 23.76 feet (36 links) =

89.76 feet; and Raft Lock Length -- 660 feet (10 chains), plus 12.54 feet (19

links) = 672.5 feet.

The 90 foot length of the Guard Lock is slightly longer than the normal length of a Middlesex Canal lift lock, and more than the minimum required to pass a 75 foot freight boat, the longest permitted on the canal. This left 15 feet of clearance for the lower miter gate to swing open and closed unobstructed by the boat; about double what was essential. It may be that the guard locks were made longer to pass additional water into the canal channel, to permit several smaller boats or rafts to be locked through at the same time (or maybe they were just built by a stubborn, independent thinking, “Yankee contractor”). That this dimension at least makes sense, gives confidence that the 672.5 foot length is probably also correct for the length of the Raft Lock.

This raft lock length, though, introduces a small mystery. The Middlesex Canal regulations specified that bands of rafts should not exceed 500 feet in length. So, why were the raft locks 670 feet long? No explanation is given, however it seems reasonable to assume that the additional length was deliberate and may have been provided for “stopping distance”. Certainly the bands were quite heavy, probably weighing in at several hundreds of tons; and, though they only traveled at a maximum of 1-1/2 miles per hour, once they were in the lock it would have taken considerable effort, and time and distance, to stop their forward motion.

At this point it seems reasonable to ask why the guard locks were so adapted, but not the lift locks. Unlike the lift locks, used throughout the canal specifically to move boats or rafts to a higher or lower elevation, the principal purpose of guard locks was protection of the canal. Only when the river level was unusually high were they needed to make more than a slight elevation adjustment to vessels passing through. The guard locks, therefore, were easily extended to create the raft lock configuration. And, of course, at this location the entire river volume was available to fill the extended lock.

Likely money played its part as well; the Middlesex struggled economically throughout most of its life, thus there may never have been money enough to similarly adapt other locks. Also likely, the Middlesex Canal Company may have done just enough to entice lumbermen to use their canal and, once this was accomplished, found no compelling need to do more. The timing suggests that this was an early, innovated project of John Langdon Sullivan, as the newly appointed “agent” of the company.

Could this have been done elsewhere? In the case of the three-lock staircase that lifted boats and rafts from the Merrimack to the Concord River level, and the two-lock staircases, of which the Middlesex Canal had four - three at Stoddard’s Locks (a.k.a. Horn Pond) and one at Gardner’s - implementing comparable modifications at these would have been an engineering and construction challenge.

But the MCC might have done something similar with the six single locks (Nichol’s, Gillis’, Stone’s, Gilson’s, Malden Road and Mill Pond), to similar advantage. A variation of this was done, many years later, on the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal. There, two freight boats were sometimes linked in tandem, with two boats towed by one team of “critters” (probably mules). To accommodate tandem boats, double-length “tandem locks” were constructed such that, if a single boat needed to be locked through, to save water only the “outer” lock segment would be used; but if a tandem boat needed to pass, the full double-length of the tandem locks was used.

How long did it take to make a trip with a band of log rafts? Such trips, one way, would likely have taken about a week, and 10 days or so does not seem unreasonable. The duration of the trip on the river would, of course, depend on such factors as: where the trip began (the distance from Concord New Hampshire to Middlesex Village was 52 miles; rafts could originate from nearer or farther), the number of locks that had to be negotiated, and the number of rafts in a band. Consider too that the Middlesex Canal was 27 miles long and that rafts and bands were only allowed to travel at 1.5 miles per hour (probably the walking pace of oxen pulling a great load*); also they were required to yield priority to all other craft on the canal and thus were subjected to occasional delays.

If there were no locks at all to negotiate, and the rafts never needed to stop moving, it would have taken about 18 hours just to travel the length of the canal at the allowed pace. But there were twelve lift-locks or lift-lock sets (three- and two-lock staircases) to negotiate if the rafts traveled all the way to the Charlestown Mill Pond. Considering that, at each of these, the band was disassembled, individual rafts locked through, and the band reassembled; also that men and beasts both needed to be fed and rested. It is not likely that any of them ever made it through the Middlesex Canal, alone, in less than a couple of days.

A Tribute to Jane Boyd Drury

by Bill Gerber

|

|

Among the many “hats she wore”, Jane and her husband Bill were 40-year members of the Middlesex Canal Association and served for many of those years as members of the Board of Directors. Jane also served as Chelmsford’s delegate to the Middlesex Canal Commission.

A native of Waterbury, Conn., Jane was valedictorian of her high-school class and earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from the New Jersey College for Women, now part of Rutgers University.

In the early 1970s, Jane became interested in local history and was known for her careful and precise historical research of the old homes, schools, monuments and burial grounds in Chelmsford. Her research extended into Middlesex Village, the northern terminus of the Middlesex Canal and pioneer development of the steam towboat. She was responsible for persuading Chelmsford Town Meeting to grant an easement to the MCA for the town owned portion of the canal and towpath. Jane created detailed historical records that are now kept in the Chelmsford town archives, in a collection named for her. In 2004, the Chelmsford Historical Society presented her with its Guardian Award and she was chosen to be one of two marshals for the town’s 2006 4th of July parade.

One MCA Board member recalls: The MCA could use a hundred Jane Drury’s. [She was] very loyal, intense, dedicated and reliable. She loved Hawaii [and] recommended Kauai - where [she and her family] went because it reminded her of the “old Hawaii.” They loved the small ship cruises. Another noted: I first knew her when she came to Harvard to do some research in my office - she was always special.

Jane and Bill celebrated their 53rd wedding anniversary on Oct. 9th 2008. Jane died at her home on March 28 after a long battle with ALS. She was 77. A memorial service was held on Saturday, April 11, at the First Parish Unitarian-Universalist Church in Chelmsford.

MISCELLANY

The Middlesex Canal Fall Walk in October 2008 followed two watered sections of the canal north and south of Route 128 in Woburn which in the years after the demise of the canal provided the right-of-way for a branch of the B&M Railroad. The walk, led by Robert Winters and Dick Bauer and attended by approximately 50 people, commenced at the cinemas on Middlesex Canal Park and headed south along the canal before turning back. Walkers then shuttled to the Baldwin Mansion and walked north along the stretch of the canal from Alfred Street to School Street. The Spring Walk takes place on Saturday, April 25, 2008 starting at Sandy Beach on the Mystic Valley Parkway in Winchester.

Dick Bauer of the Middlesex Canal Commission provides some history lessons

about the Middlesex Canal during the 2008 Fall Walk

Middlesex Canal webmaster Robert Winters has been very busy scanning, proofreading, and posting back issues of Towpath Topics on the Middlesex Canal Association website. There are now 76 out of 105 back issues posted (and enhanced where appropriate). Robert hopes to get the last 29 issues up and available for search engines to discover within the next month or two. You’ll find all the old issues at http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath together with tables of contents for all of issues published since 1962. The search box on the main page of the MCA website will help you find back issues containing specific topics.

WEBSITES

Middlesex Canal Association: www.middlesexcanal.org

Lowell National Historic Park: www.nps.gov/lowe

Masthead - Excerpt from a watercolor painted by Jabez Ward Barton, ca. 1825, entitled View from William Rogers House. Shown, looking west, is the the packet boat George Washington being towed across the Concord River from the Floating Towpath at North Billerica.

Back Page - Excerpt from an August 1818 drawing of the Steam Towboat Merrimack crossing the original Medford Aqueduct (artist unknown).

FUNCTION ROOM RENTAL

For the past seven years a group of dedicated volunteers has operated the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center at the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica. Throughout this time, the generosity of the owner allowed us to stay there rent free. However, he now feels it essential to charge us rent.

We do have good facilities for rental in a charming Museum. Should you plan a function, we hope that you will consider us. A very reasonable charge of $200 covers the room and a committee member who will be present throughout to assist you. For more information phone 978-670-2740; leave a message and someone will return your call.

This issue of Towpath Topics was edited by Bill Gerber and published and mailed by Robert Winters. Articles and photographs for future issues are always welcome.