Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 48 No. 2 | February 2010 |

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

by Bill Gerber, President pro tempore

978-251-4971

wegerber@gmail.com

A hearty and sincere Thank You to all who have contributed to our annual appeal. (Please note that our campaign is still open and our treasurer continues to tally donations.)

Please mark your calendars. A Reception for our "artist in residence", Tom Dahill, without whose art work our Museum would not exist, will be held on February 20th, with an Exhibition of his work from Feb. 13th to the 28th; the Spring Walk - on April 24th; and the Annual Meeting - on May 16th. See the Calendar, following, for more information on all of these. Also included in the calendar are meetings and tours, sponsored by other groups, in which you may want to participate. Please check our web site periodically, at the URL noted above, which sometimes lists additional canal-related events and topics potentially also of interest.

Hip, hip hooray! (x3) It's done! The entire Middlesex Canal has now been placed in the National Registry of Historical Places, officially as of November 9th. Our perpetual thanks to Tom Raphael and Susan Keats for their diligence, tenacity and hard work. A copy of the certificate announcing this achievement is reproduced in this issue, along with Tom's summary article telling of the 13 year quest to reach this status.

To update you on Nolan, he was able to attend the Fall Meeting and has since attended several meetings of the Board of Directors. More specifically, he has regained weak and limited, but functionally useful, use of his left arm; and enough use of his left leg to enable him to walk short distances with a walker. He is able to enter and exit an automobile, though still with difficulty.

The need to raise money to sustain our museum remains a most serious concern. Students of the Middlesex Community College undertook a project to come up with ideas for the MCA to earn enough money for us to pay our rent. On December 18th, several members of the BoD, and friends, attended a presentation by the students' of their ideas. These are now being further considered by our ad hoc museum committee.

As you realize the board as a group has a limited perspective about solutions, which is why it is valuable for us to garner ideas from outside our tight circle. Certainly, we also value ideas from our membership and welcome your thinking on this subject. Please contact me at <wegerber at gmail dot com> with your ideas.

At the beginning of our December BoD meeting, we met with Liana Measmer, Owner and Editor of The Billerica Green, a new monthly newspaper serving Billerica; see www.thebillericagreen.com. Liana has taken an interest in the canal and has, very recently, published one article about it. Very likely there will be more. Furthermore, Liana's Calendar section should provide another means for the MCA to announce our own future events.

We're experimenting! Some time ago we established an 'email group' to share information and discussions among members of the Board of Directors. Since many regular members and some of the museum visitors have also given us their email addresses, we thought it might be useful to establish something of this nature to share information with all of you, also to broaden the audience for our appeals for volunteers to help staff the museum on weekends. This latter 'email group' could also be a means for members to communicate with the BoD. Initially, however, the default setting for a message from a member was that it would be sent to all others, and this could become annoying. We're looking for a way to provide a direct, exclusive - member-BoD-member - link. It should be easy, right?

Traci Jansen is at it again! She will be running a children's workshop at the museum on February 18th. See the Calendar for that date for more information. (Go Traci!)

Our bookstore has sold out of Lewis Lawrence's manuscript on the history of the M'sex Canal. J. J. Breen has taken on the task to correct the few typos that appeared in the first edition. A second edition printing will be made as soon as these corrections have been completed.

From the Spring 2008 issue of Towpath Topics, Dave Dettinger's article about "The Canal that Bisected Boston" (aka the Mill Creek Canal), will be reprinted in a forthcoming edition of American Canals, the newsletter of the American Canal Society. Dave has been working with editor Linda Barth (ACS, CSNJ) to prepare his article for republication.

And that's about it for this issue.

Bill Gerber

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE (JONES)

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

JAMES SULLIVAN'S RESTING PLACE - a correction

MIDDLESEX CANAL NATIONAL REGISTER CHRONOLOGY

SULLIVAN'S TOWBOATS (GERBER)

MISCELLANY

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

Middlesex Canal Association (MCA) and related organizations

First Wednesday: MCA Board of Directors' Meetings - The BoD meets, from 3:30 to 5:30pm, the first Wednesday of each month. Members are welcome to attend.

Sun, Jan 31, 2010: MCA Winter Meeting, beginning at 2:00pm. A Double-header! Tom Raphael will report on his recent attendance at the 2009 World Canals Conference, held in Serbia in September. Then Fred Lawson will inaugurate a new talk about the Middlesex Canal, developed from photographs taken by Leon Cutler in the early 1930s. The meeting will be held in the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center in the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica.

Feb 1-28, 2010: Lincoln and Illinois & Michigan Canal exhibit. Lock 16 Visitor Center 754 First Street LaSalle, IL 61301. For information, contact Katie MacKay, 815-220-1848 or <reservations at canalcor dot org>.

Feb 18, 2010: Children's Workshop. An educational program about the Middlesex Canal for children in grades 2 and 3. To be held from 10:00am to 12:00pm at The Middlesex Canal Museum, 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica. For directions to the museum, see the MCA Winter Meeting notice, above. The $15 enrollment fee includes membership to the MCA. For further information contact Traci Jansen at <middlesexcanal4kids at gmail dot com>.

Sat, Feb 20, 2010: Reception Honoring Tom Dahill; without whose art work our Museum would not exist, and for which invitations with more detailed information will be mailed to our members and other guests. An Exhibition of Tom's work will be on display in the Reardon Room of the museum from Feb 18th to 28th.

February 25, 2010: I&M Canal Corridor Association Annual Luncheon, Drake Hotel, Chicago. For an invitation, contact Katie MacKay, 815-220-1848 or <reservations at canalcor dot org>. Lock 16 Visitor Center 754 First Street LaSalle, IL 61301.

March 6, 2010: CSNY Winter Symposium, Monroe Community College, Rochester, NY. Contact: Tom Grasso <tgrasso1 at rochester dot rr dot com>.

March 13, 2010: C&O VIP Work Party, 9 to 12 noon. Painting the Georgetown canal boat. Contact Jim Heins (301-949-3518 or <vip at candocanal dot org>).

March 13, 2010: National Canal Museum, Canal History & Technology Symposium, Easton, PA. Call 610-559-6613; www.canals.org.

April 9-11, 2010: Canal Society of Indiana - "Hoosiers on the Move" - Headquarters: Comfort Inn, Richmond, Ind., 765-935-4766; room rate: $61.60 includes tax. Tour will cover the Whitewater Canal, National Road, Quakers, Politicians, and Underground Railroad in Wayne County, Indiana. Carolyn Schmidt, <indcanal at aol dot com>; 260-432-0279.

April 9-11, 2010: Virginia Canals & Navigations Society spring conference, Harper's Ferry, WV. Sat. field trips. Bill Trout, 252-482-5946; <bill at vacanals dot org>.

April 16-18, 2010: Pennsylvania Canal Society Spring Field Trip: upper grand section of the Lehigh Canal. Contact: Bill Lampert, <indnbll at yahoo dot com>, 215-262-5506.

April 17, 2010: Annual Douglas Memorial Hike and Dinner. Three different hike length options with bus transportation provided. Cumberland to Spring Gap area with dinner and evening program at the Orleans Volunteer Fire Dept. Dorothea Malsbary, 301-942-2528; <Programs at CandOCanal dot org>.

April 23-25 or April 20-May 2, 2010: "Bridging the Tuscarawas Gap" - See trail development along the Ohio & Erie Canal, restored toll house, Trenton dam and feeder & Lock 15 Park. Contact Larry Turner, 330-658-8344 or <towpathturner at aol dot com>.

Sun, April 24, 2010: MCA-AMC Spring Walk. Middlesex Canal; Joint with Appalachian Mountain Club; meeting time 1:30pm. The walk will originate from the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center in the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica. It will be conducted for 2-3 hours, rain or shine, over 3 to 4 miles of generally level wooded terrain and streets. The route follows the canal south of the Concord River. Sites to be visited include a guard lock, an anchor stone for the floating bridge which once carried the towpath across the river, and many stretches of canal, some still watered. No registration required, for more information: call walk leaders: Roger Hagopian 781-861-7868 or Robert Winters 617-661-9230; robert@middlesexcanal.org. For directions to the museum, see the notice for MCA's Annual Meeting, below. The Museum and Visitor Center, and the bookstore, will be open from 12 noon to 4pm.

May 1, 2010: Canal Walk/Ride. Join the Canal Corridor Association in Morris, IL for the third annual I&M Canal Walk or Ride Celebration. Walk one to five miles or bike ten to twenty-five miles during this fun, family event. Bring a group from your business or invite some friends and make it a team effort! Contact Katie MacKay, <reservations at canalcor dot org> or 815-220-1848.

Sun, May 16, 2010: Annual Meeting of the Middlesex Canal Association. This meeting will elect a new slate of Officers and Board Members. The speaker and topic are yet to be determined. The meeting will be held in the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center in the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica, beginning at 2pm.

Directions to the Museum/Visitors Center: Telephone: 978-670-2740.

By Car: From Rt. 128/95, take Route 3 toward Nashua, to Exit 28 "Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle". At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at a fork. After another ¾ mile, at a traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A. Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road, Talbot Street, which will put St. Andrew's Church on your left. Go about ¼ mile and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the falls, where Old Elm becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the falls.

From I-495, take exit 37, N. Billerica, south to the road's end at a "T" intersection, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700' and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street.

By Train: The Lowell Commuter Line runs between Boston's North Station and Lowell's Gallagher Terminal. Get off at the North Billerica station, which is one stop south of Lowell. From the station side of the tracks, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station and Faulkner Streets on the right side.

May 21-23, 2010: Canal Society of New York State Spring Field Trip: Champlain Canal and the PCB cleanup project at Fort Edward. Headquarters: Queensbury Hotel, Glens Falls, NY. Room rate: $99 plus tax; 518-792-1121. Check the web, www.canalsnys.org for updates.

May 22, 2010: CSNY, Dedication of restored Nine Mile Creek Aqueduct, Camillus Canal Society, Camillus, NY. Contact Dave and Liz Beebe, <dwbeebe at verizon dot net>.

June 19-20, 2010: Heritage Transportation Festival, Delphi, (IN) Canal Park. 1850 transportation, canal boat rides, high-wheel bicycles, carriage rides, etc. See the W&E web site at www.wabashanderiecanal.org, or contact Dan McCain at <mccain at carlnet dot org>.

September 19-24, 2010: World Canals Conference, Rochester, NY. Contact: www.worldcanalsconference.org. Post conference tours Fri, Sept 24. Check www.wccrochester.org.

October 1-16, 2010: Study tour of south German waterways. Contact Tom Grasso, www.canalsnys.org.

October 8-10, 2010: Pennsylvania Canal Society fall trip.

October 22-24, 2010: "River Boats, Pirates and Caves." Headquartered in Evansville, IN. Bus tour of southeastern Illinois, Cave In Rock, Garden of the Gods, Ohio River locks, Paducah, Kentucky flood wall murals (possibly Quilters Hall of Fame and the Civil War Museum) on Saturday. Friday tour of LST in Evansville, Sunday Wabash & Erie Canal in Warrick County Indiana. Carolyn Schmidt, 260-432-0279; <indcanal at aol dot com>.

JAMES SULLIVAN'S RESTING PLACE

An error to correct - Ed.

In the Fall 2009 issue, Howard Winkler provided an article on the burial site of James Sullivan, investor, principal promoter, and first President of the Middlesex Canal Company; later a Governor of Massachusetts. I missed a photograph that Howard sent, as follows:

Governor James Sullivan lies in a shared tomb in the Granary Burial Ground located on Tremont Street in Boston.

Gov. James Sullivan on left – Gov. Richard Bellingham on right

MIDDLESEX CANAL NATIONAL REGISTER CHRONOLOGY

by Thomas Raphael

The Middlesex Canal Association (MCA) was incorporated in 1964 and in 1966, the intact remnants of the canal, from Woburn to Chelmsford, were placed in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1977 the Middlesex Canal Commission (MCC) was authorized and three noted archaeologists, the Industrial Archaeology Associates (IAA), were hired to provide a comprehensive inventory of the canal. They traversed and recorded, including aerial photographs, the whole route of the canal, its location, its condition and significant features. In 1980 they published the Middlesex Canal Heritage Park Feasibility Study, which recommended preservation and reuse of the canal. In 1980-1985, the MCC placed stone monuments with brass plaques, showing the route of the canal, in each of the nine canal communities through which the canal passed.

In 1996 the Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC) suggested that the complete length of the canal should be recorded in the National Register. A review at the Metropolitan Area Planning Commission (MAPC) indicated that there were no maps that showed a detailed record of the current lots along the canal route in the overbuilt parts of Charlestown, Somerville, Medford and Winchester. These would be needed for the National Register as well as for any restoration effort. In March 1996 Tom Raphael started the deed and assessor map research to enable the MAPC's Geographic Information Systems (GIS) laboratory to assemble a Map Book. This produced a corresponding, community by community, list of the canal lot owners.

Concurrently, on October 20, 1997 a group of 17 people met at the National Park Service Office in Lowell to form a committee to consider the MHC proposal to revise the National Register. Present were Bruce McHenry, leader (MCA), Nolan Jones (MCA), Tom Raphael (MCA, MCC) , Betty Bigwood (MCA, MCC), Bettina Harrison (MCA), Mike Wurm (National Park Service, Lowell), Thomas Mahlstedt (Metropolitan District Commission (MDC, MCC), Paul Spina (MAPC), Frank Noonan (MHC), Brian Knight (MHC), Michael Steinitz (MHC), Jessica Rowcroft (MHC), Leonard Lopata (MHC), Virginia Adams Public Archaeology Laboratory (PAL), James Garman (PAL), Paul A. Russo (PAL) and, Mathew A. Kiersttad (PAL). They agreed to pursue placing the whole route of the canal on the National Register.

In September 1998, using an MHC Grant, the PAL was hired to prepare the basic nomination information. PAL accumulated all available historic and background literature, researched the archaeological resources, the environmental setting and the Native American usage from the Paleo-Indian Period (12,000 BP). They walked and photographed the canal corridor and prepared a complete description of current conditions. In September 1999, PAL submitted their report.

In an April 12, 2000, letter to Nolan T. Jones (President, MCA) MHC said that, based on MHC files, research by MCA and the PAL Survey and Planning Report, the canal should be eligible for nomination to the National Register and that Betsy Friedberg and Leonard Lopato of MHC would be available to explain the format and answer questions on how to proceed. As the information was being assembled and the work progressed, it became obvious that a professional historic consultant would have to be hired to complete the nomination.

Susan Keats, a professional who had done several nominations of Winchester historic districts, offered to prepare the canal's National Register Nomination, at no charge. On February 2002, all of the previous work was now turned over to Susan to be assembled into the required format for the nomination. By September 3, 2003, Susan sent MHC the preliminary sections, the narrative, the matrix of data sheets and the Map Book, for review. These three separate documents now had to be arranged so they were consistent with each other. They were reviewed at every step by each of the specialized members of the MHC staff.

As the nomination was being developed, it was found the property lots of the canal owners could not be accurately superimposed on MassHighway Street maps or State GIS or United States Geological Survey (USGS) maps. Waterfield Engineering Associates (WEA) proposed and was hired to sequentially scan all the assessor plates and configure them into a Map Book. The owners of the lots the canal formerly ran through were identified, and meetings were conducted by MHC in each community to notify owners of the nomination and receive their comments and approval.

On March 15, 2006 in a letter from MHC to Nolan, the canal was declared eligible for inclusion in the Massachusetts State Register of Historic Places and for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. However, in December 2006, MHC requested further work to include a number of non-related structures of the period along the canal. This required new research, segment by segment, and then the addition of the new compilations to the corresponding segments of the Map Book and the matrix of data sheets. This was completed by January 2008. By this point, however, new photographs of the current conditions were needed, as the previous photos were ten years old. On March 4 2009, Nolan Jones submitted the new photographs.

On October 2, 2009 MHC submitted the nomination to the National Park Service for inclusion in National Register.

In Summation

This whole project lasted 13 years, involved countless hours of volunteer effort, of salaried staff and direct contract costs in excess of $50,000. The Middlesex Canal now has one further record to assure its rightful place in history.

Thomas Raphael, November 3, 2009

JOHN LANGDON SULLIVAN

THE DEVELOPMENT AND USE OF HIS STEAM TOWBOATS

by William E. Gerber

E-mail: <wegerber at gmail dot com>

This paper addresses John Langdon Sullivan's successful efforts to develop steam powered towboats, and their role in extending commercial shipping into northeastern Massachusetts and south-central New Hampshire, also into other east coast watersheds.

BACKGROUND

Histories of the Middlesex Canal state that steamboats were tried on the canal, that they were used for only a few years1, were ultimately not successful and were abandoned by 1820.2

But early in 1820, Sullivan stated:

"In the freshets, and generally, the steam towing boat has been very useful, being able to take two loaded boats against the current when they could not have moved at all - at other times carrying them in half a day as far as they would have gone in two by the ordinary means . This boat has served to prove the practicability ... through [New Hampshire and Vermont] ... ."3

This is NOT a testimonial to failure or impending abandonment. So why the dichotomy between Sullivan's statement and the historical accounts?

Earlier historical accounts miss several points; and recently found evidence suggests they are simply incorrect. The towboats operated, not on the Middlesex Canal, but on stretches of the Merrimack River where it was impractical to build towpaths. And, no boating company records have been found, only the records of the Middlesex Canal Company (MCC) have survived. In 1820, when Sullivan was replaced as "Agent" for the MCC, his reports to the MCC Proprietors - of the operation of the Merrimack Boating Company - ceased, including reports about steam towboat development and use. (This appears to have led some historians to conclude that steam towboats were abandoned in this year.)

Key Reference Missing On page 143 of Christopher Roberts' book (his PhD thesis) "The Middlesex Canal" there is a footnote that reads "The material in this and following paragraphs, … , is drawn from an eight-page memorandum, elaborated for submission in 1813 to a board of referees chosen to decide a dispute between J. L. Sullivan and Robert Fulton. Opposite each fact there detailed is listed the supporting evidence: affidavits, correspondence, acts of the legislature, etc. This document is with the records of the Middlesex Canal." Regrettably, this item is not among the corporate records archived at the Mogan Center in Lowell. If anyone knows where this item can be found, please contact me via the phone number or email address in the masthead. |

In 1808, Albert Gallatin (Thomas Jefferson's Secretary of the Treasury, who was conducting a national survey of internal improvements) declared: "The Middlesex Canal, uniting the waters of that [Merrimack] river with the harbor of Boston, is however the greatest work of the kind which has been completed in the United States."4 But there was a problem: the canal was not being well managed and it was losing money. In that same year, John Langdon Sullivan (son of James Sullivan, lawyer, the principal promoter of and investor in the canal, and by then governor of Massachusetts) was hired as "agent" for the canal company; today we'd call him the "CEO".

Sullivan's first task was to make the canal sufficiently profitable to support its own maintenance, which he quickly did. He also introduced or established tighter regulations for using: "Landings", official cargo transfer points, to account for the transshipment of goods and control the collection of tolls; and "Passports", to authorize the passage of boats through the locks. He set up good operating and maintenance procedures (such as by keeping the channel clear of plant growth, filling in muskrat holes, repairing locks and aqueducts, and upgrading the quality and durability of canal structures) to bring the canal to a reliably serviceable state; he opened the Concord River, for more than 10 miles, to become an artery of commerce, and he established and enforced rules and regulations for the operation of boats and rafts on the canal, so as to protect and preserve the physical resource.

But Sullivan's responsibilities also included extending the canal's reach into the wilds of central New Hampshire. Over the next seven years he accomplished this too, cooperatively, by: providing technical and financial assistance to other canal companies that were attempting to build short canals around discrete falls and rapids on the Merrimack River; initiating improvements at four of the lesser rapids, and later, constructing canals at two of these sites.

Under his guidance, the Middlesex Canal Company provided so much assistance to the independent river canal companies that, by the time the route to Concord, New Hampshire, was open, the Middlesex Canal Company held controlling interest in all but one of the river canals. With this, they were able to consolidate the operation of almost the entire system.

By 1815, the Middlesex Canal was only about a quarter of more than 120 miles of canals and river navigations that extended: by the Merrimack River from Concord, New Hampshire, to Newburyport Massachusetts; or to Concord, Massachusetts, Medford and Charlestown by diverting through the Middlesex Canal; and from the canal's southern terminus across the Charles River into Boston's Haymarket and Boston Harbor, or upstream to Cambridge and points beyond.

In addition to being a good business man, ambitious, energetic, and technically competent, Sullivan was a visionary. In 1811 he delivered a paper in which he described practical means for conducting commerce by canal across New York state, and of opening up the midwest to commerce transported across the Great Lakes on boats powered by steam engines.

In that same year, 1811, Sullivan saw a personal opportunity to profit from the canals. He set up his own freighting company, the Merrimack Boating Company (MBC)5, to ship goods between Boston Massachusetts and Concord New Hampshire, and the towns along this route. It was in support of MBC interests that he initiated his development of towboats. In April 1814, his efforts were rewarded with the award of the first patent ever issued by the USA for a towboat; the first of sixteen patents that were eventually awarded to him.6

Once this company was operating successfully, Sullivan attempted to replicate it on other east-coast rivers, notably the Hudson (New York), Connecticut (through Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire & Vermont), Savannah (Georgia), and Santee and Cooper (South Carolina) Rivers.

In an 1818 paper, published in Connecticut,7 Sullivan outlined his concept and plans to build three classes of towboats. These were: small boats that could ply the upper reaches of rivers, like the Merrimack and Connecticut; more powerful medium size boats, plain & strong, to tow vessels in tidal waters, e.g., between Hartford and Saybrook on the Connecticut; and large boats that could tow other vessels in coastal waters, e.g., to and from New York City, or Boston upon completion of the Cape Cod Canal.

However, as agent for the Middlesex Canal Company, Sullivan may have taken better care of the canal system than he did of his investors. In 1818, the Proprietors changed his compensation from a salary of $1500 per year plus 5 per cent of the canal income, to the same salary plus 5 percent of the dividends.8 Two years later, in early 1820, he was replaced by James F. Baldwin. (Subsequently, investor dividends jumped from $10 per share issued in 1821 by Sullivan, to $20 per share in 1822 by Baldwin.9 But by the following year, boatmen were complaining that some of the river locks were nearly impassable due to silting, and of one lock gate being off its hinge.10) In the aftermath of his departure, Sullivan's reports to the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal Company, e.g., of towboat development, were terminated.

In 1821, still the sole proprietor of his Merrimack Boating Company but no longer agent for the Middlesex Canal Company, Sullivan set up yet another company - the Boston Steamboat Company. Through this firm, he endeavored to continue his efforts to establish shipping companies on other east coast rivers and to equip with them with towboats of his design.

Then, in 1823, a rival shipping company, the Union Boating Company, was established in New Hampshire. This company proceeded to undercut, by half, the shipping rates charged by the Merrimack Boating Company, thereby taking away many of the MBC's customers. However, within months of its beginning, the Union Boating Company suffered the loss of a boat, wrecked,11 and was forced to terminate operations.

Though the loss of business lasted for only a short time, Sullivan's substantial infrastructure, together with the need to maintain a regular shipping schedule, left the Merrimack Boating Company owing lockage fees to the Middlesex Canal Company that it couldn't pay. Sullivan's request for forbearance was refused and the Merrimack Boating Company was forced into insolvency. It was soon dissolved.

The assets of the two boating companies were bought up by other investors, foremost among them two of Sullivan's brothers, William and Richard, and his principal antagonist at the Union Boating Company, Richard Ayer. These men incorporated as the Boston and Concord Boating Company (B&CBC), and resumed the shipping operations of both companies.

Evidence strongly suggests that the B&CBC continued to use Sullivan's 1818 towboat, and likely the 1816 boat as well, perhaps until 1842/43 when railroad competition finally brought about that company's demise. In fact, the 1818 boat became known as the B&CBC's towboat.12

THE EARLY CHALLENGE

When the Middlesex Canal opened, in 1804, travel on the Merrimack River was impeded by multiple falls and rapids. Over time, these were overcome by short canals and other improvements that bypassed discrete rapids; most of these bypass canals were built by independent companies.

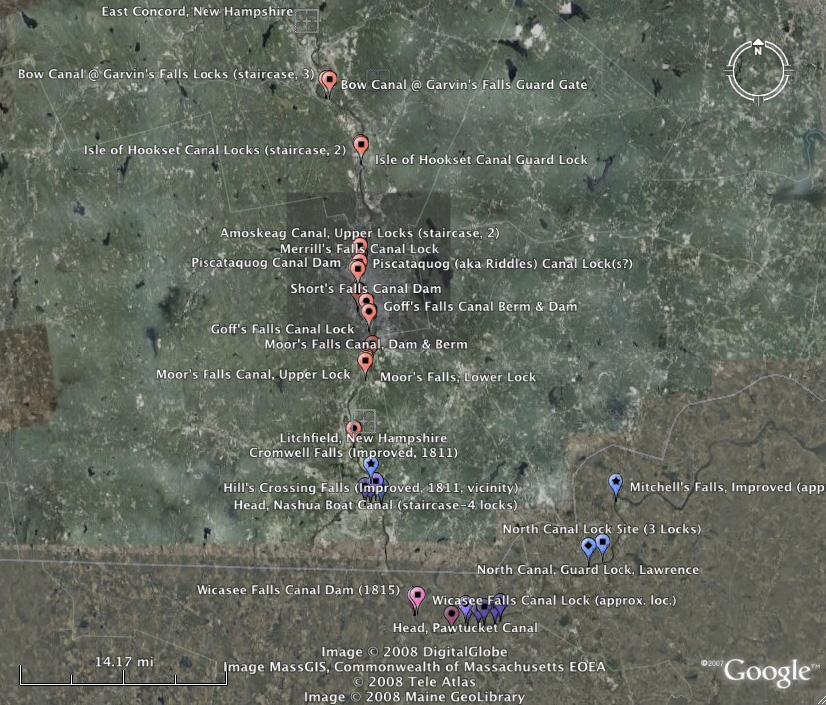

Figure 1. Chronology - Canal Construction vs Towboat Development

Figure 1 is a chronology showing the time from when each of the canal companies was incorporated - until construction was completed and each canal was opened to commercial traffic; also shown are the years that improvements made lesser rapids passable. The years are arrayed across the top. The chronology also compares - the years in which Sullivan's towboats were completed and, from Generation-3 on, placed into service - with the periods of canal construction.

Shown at the bottom of the chart, "The Proprietors of Locks and Canals on Merrimack River" was incorporated in 1792. This company constructed the Pawtucket Canal and made improvements to seven other rapids in Massachusetts (Wicasee, Hunt's, Varnum's, Peter's, Parker's, Bodwell's and Mitchell's). This made the river passable for "boats, rafts and masts", from the Massachusetts border to tidewater, as required by their Act of Incorporation; this portion of the Merrimack was opened to traffic in the spring of 1797.

Other canal companies quickly followed. In 1808, when Sullivan was appointed agent for the Middlesex Canal Company, nine river canals had been authorized in New Hampshire and were under various stages of construction. Sullivan's 1809 report to the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal stated that river canal construction would be completed the following year. Alas, it was not, neither then nor the following year. And so, in 1810, Sullivan began to develop his towboat concept.

In 1811, the Middlesex Canal Company made improvements to four lesser rapids (Cromwell's, Hill's (aka Hill's Crossing), Taylor's and Wicasee) to make them passable and thereby open the river as far north as Moor's Falls Canal in upper Litchfield, New Hampshire. Likely, these improvements generally replicated and, in the case of Wicasee, functionally restored what the Merrimack Proprietors had done more than a decade earlier.

Sullivan's first two experiments were not successful and it was not until late 1812 that he had a usable towboat. By that time, construction at six of the nine canals, noted above, had rendered them usable. Construction of the remaining three was finished late the following year, and work on the final two would commence the year after that.

Note that, in 1815, Amoskeig Canal replaced Blodgett's Canal.

At least two of the four rapids that were improved in 1811 still presented obstacles. In 1812, Sullivan established a New Hampshire company to build a canal around Cromwell's Falls; within a year he turned management and construction of this canal over to the Union Canal Company. The following year he obtained legislative authorization for the Middlesex Canal Company to construct a canal at Wicasee (aka Tyngs) Island. These last two canals were not completed until late 1815. But, as early as 1814, Sullivan's 1812, "third generation" towboat, with its "Warping Windlass" enabled his freight boats to ascend the river through the four improved, but not yet bypassed, rapids.

HOW, WHEN AND WHY DID IT END?

Earlier historians offer several reasons for abandonment of steamboats. They claim: the advantage of steam was offset by delays at the locks13; rocks and sunken logs presented a continual menace14; and canal banks were jeopardized from the surging wash created by the paddle wheels.

Were these reasons even relevant, none appear to be serious enough to have ended the enterprise. More likely, the reason for cessation of development is rooted elsewhere.

Consider that Sullivan's early attempt to establish a freighting business on the Connecticut River was thwarted by the Connecticut legislature. In 1820, he left (or was forced out of) his position as Agent for the Middlesex Canal Company. His repeated appeals for authorization to operate in New York, in coastal waters and on the Hudson River, were consistently thwarted; and partly because of this, at one point, he was forced to sell a large steamboat, presumably at a considerable loss. In 1823, the towboat Patent was lost in South Carolina, at another significant loss. And in that same year, his own Merrimack Boating Company was forced into insolvency.

By mid-1823, these setbacks left Sullivan with a loss of both purpose and financial means. However, it was only his towboat development efforts that ended. Evidence suggests that his 1818 boat, and possibly his 1816 boat, continued in service on the Merrimack, perhaps until the end of the canal era, and maybe even beyond that.

FIRST GENERATION TOWBOAT - 1810

Critter Power -

Christopher Roberts, the Middlesex Canal's foremost historian, states that Sullivan's first attempt to develop a towboat "... contrived a machine to move paddle wheels ... by the power of men, horses or oxen, for the purpose of towing other boats astern." He continues, the "... mechanism furnished insufficient power."15 Most likely, this effort was quickly abandoned.

Figure 2. Treadmill Mechanism for Transferring Power

Aside from noting the use of "critters" to move paddle wheels, there are no details to tell us what this boat may have looked like. However, there are clues. At that time, several mechanisms were in use to power "horse boats" and "horse ferries". Of the several mechanisms available, only a treadmill would have enabled construction of a boat sufficiently narrow to fit into a canal lock. Conceptually, this mechanism might have been as shown in Figure 2.

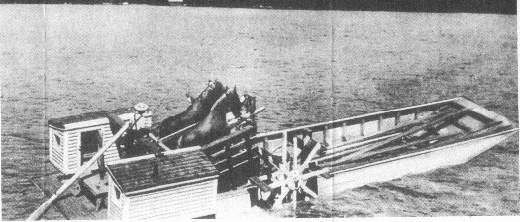

A horse-boat, which operated into the early 20th century on Lake Winnipesauki, in New Hampshire, and employed such a mechanism is shown in Figure 3. Ignoring the sheds on either side of the stern, note that the two horses, and the structures that constrain and tether them, occupy much of the width of the boat, leaving only limited space on the right side for the operator to move between bow and stern.

|

| Photo Courtesy of the New Hampshire Boat Museum, Wolfeboro, NH |

| Figure 3. "Two Horsepower" Winnipesauki Work Boat |

The hull of this boat was about 57' long and about 9' in beam. Thus, like the earlier canal boats from which it appears to have derived, the hull itself would easily pass through a 10' x 82' lock, typical of those used on the Merrimack River and Middlesex Canals. But in this configuration, each of the paddle wheels add about 3' to the beam and so, with the paddle wheels placed as shown, the boat would not fit into a lock. Some other arrangement would have been required such as encasing the paddle wheels in trunks within the dimensions of the hull. The boat is steered with a very long oar, in this case about 17'.

Report to the Proprietors

With the failure of his first effort, Sullivan sought a source of greater power. His search led him to Oliver Evans, in Philadelphia, who, at the beginning of the 1800s, had invented a high-pressure steam engine that was both powerful and radically smaller than anything else available at that time.

In his January 1812 report to the Proprietors, as Agent for the Middlesex Canal, Sullivan stated:

"The late improvements in navigation by the power of steam-engines, now in operation on the Hudson, and the Delaware, and the Mississippi, fortunately at the moment our new canals are in readiness, admit the expectation of their being made use of, under certain modifications, to navigate our canals and Merrimack River; not merely to carry passengers, but for the far more important purpose of towing other boats loaded with merchandise."

"The various difficulties of adapting a steam-engine to boats of the size of ours have been happily overcome, in theory, by the ingenious Mr. Evans, of Philadelphia. A patent apparatus for propelling boats on a new and simple principle, having been invented by Mr. Morrison of this town, which is applicable to boats of the dimensions we use on the canal, and in such manner as to pass the locks without interfering or requiring any alteration."

"I have proceeded so far in this enterprise as to obtain an act of incorporation; have on my own account bought Mr. Morrison's patent right for Merrimack and Connecticut Rivers; have arranged the plan of the boat and engine, and have in my possession accurate drawings of them sent me by Mr. Evans, with whom I have made terms."

"A number of gentlemen have joined with me to endevour [sic] to raise the capital necessary to a boating company, with a view to benefit the property of the Middlesex Canal."

SECOND GENERATION TOWBOAT - JULY 1812

Steam Power, Engine in the Stern -

Evans used his engines to power automated flour mills of his design; but, as early as 1804, he had fitted one of his engines into a hull to build an amphibious steam dredge for use in Philadelphia harbor. (This was a steam powered vessel that, though not the first, operated successfully five years before Fulton's North River boat.)

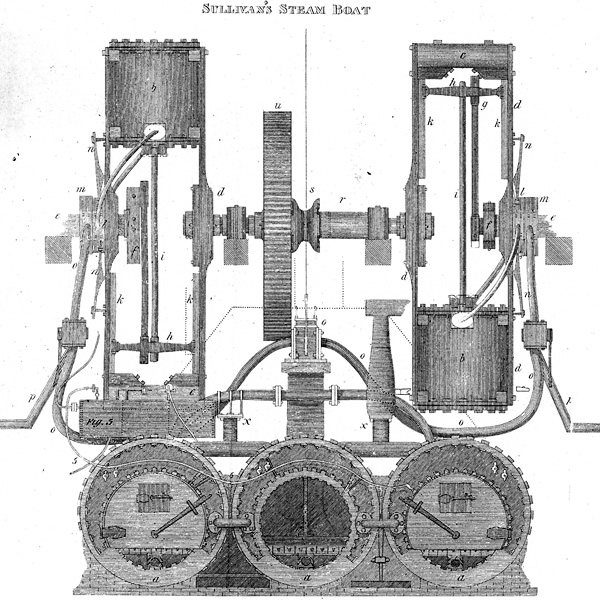

Figure 4. Evans' High-Pressure Steam Engine

In 1811, Sullivan purchased two of Evans' engines16, of the type shown in Figure 4.

This engine consisted of:

• a boiler (A) that produced steam to power

• a piston in the cylinder (B), which drove

• the beam (C) up and down. The beam in turn drove

• a flywheel (D) from which power was taken to drive the boat.

The beam, hinged at the left end, also drove

• a water pump (G) to recharge the preheater and boiler and

• an air pump (F) used to condense exhaust steam, thereby boosting power by creating a vacuum on the backside of the piston.

• (E) was a preheater, which used exhaust steam to heat inlet water before it was pumped into the boiler.

An Evans' engine was mounted in the stern of a boat, which also featured Michael Morrison's patented "Chain-Floats" drive.17 Roberts states that "the chain floats drive was disadvantageously placed in a trunk in the center of the boat and the boiler was situated so far astern that the boat drew unequal depths of water and was otherwise inconvenient."18

We can only guess what this boat might have looked like.

A Tale of Disappointment -

There is a story of two men who were taking an empty boat up the Merrimack River from the head of the Middlesex Canal, apparently at a time when one of Sullivan's steamboats began an early trial run.19 Though usually told in conjunction with the later 1812 boat (i.e., the third generation boat, discussed next), for reasons that will become apparent, the tale fits this boat much better.

The men, Moses Fletcher and William Wyman, had departed from the point where the steamboat was being prepared and were poling their boat upstream. They expected to soon see Sullivan's boat come steaming by them. It did manage to catch up to them, but moved so slowly that they decided to race it; they increased their pace and thereby were able to keep up with the steamboat. Sullivan, who was aboard the steamboat, carried on a conversation with the men. Among other things he asked who they were and how long they thought they could keep up their increased pace. Their response was that they thought they could do so all the way to their home in Tyngsborough (Massachusetts), five miles up the river.20

That Sullivan was disappointed with this boat is probably an understatement, and he quickly set out to build a better one.

THIRD GENERATION TOWBOAT - OCTOBER 1812

Sullivan's third attempt was acceptably successful; and is, perhaps, the most interesting of his towboats. It is for this boat that, in April 1814, he was awarded his first patent; which is also the subject of a story. (See below.)

During the summer and fall of 1812, in the wake of the disappointing performance of his second generation boat, Sullivan had a new hull built. It was 70 feet long and 9 feet wide.21 He installed Michael Morrison's Chain-Floats Drives under and inboard of each gunwale, and fitted an Evans' engine into the center of the hull.22 To this he added a windlass, likely on a foredeck, to which the power of the steam engine could be directed. The purpose of the windlass was to enable the boat to warp itself up rapids, along with whatever was in tow.

This boat was first tried out on the Charles River in October of 1812 and, according to John Mulholland (Oliver Evans' mechanic, who had assisted with the engine installation), this boat ran a distance of seven miles and six furlongs in 60 minutes.23 This translates to 7-3/4 miles per hour, for an hour; and this with a 20 horsepower engine in a displacement hull. The observers thought it could do better, perhaps as much as nine miles per hour. Clearly this boat was Sullivan's first success.

Again, no drawings have been found to tell us what this boat looked like. But we should be able to construct at least a mental image of it from an 1804 dredge that Evan's built. (A speculative description follows in italics.)

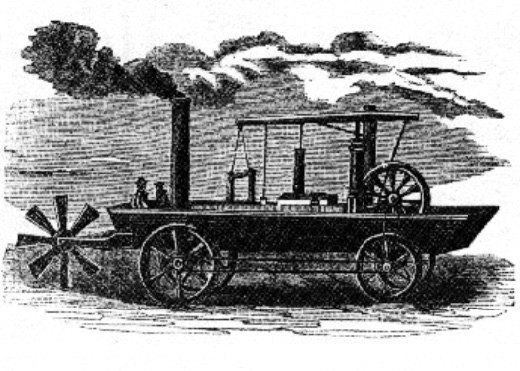

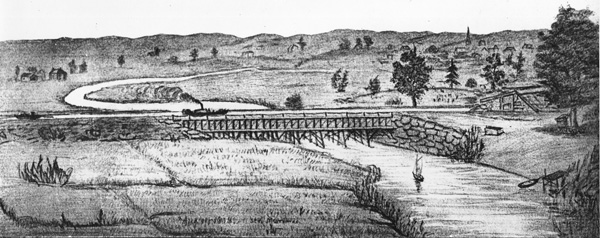

Figure 5 is an artist's sketch of Evans' dredge, which, interestingly, was a self-powered amphibious vehicle/vessel.

• The engine within the dredge probably looked much the same in Sullivan's towboat.

• But Sullivan did not use a stern wheel, so discard the eight-spoked paddle wheel and its supporting structure at the left end of the hull.

• Similarly, Sullivan's boat was not amphibious; but it did use chain-floats drives on either side, under the gunwales. These likely resembled caterpillar tractor treads with exaggerated treads (aka "floats"). So, retain only the hubs of the wheels, raise them to about mid-hull level, and wrap a "caterpillar tractor-tread" around and between the two hubs.

• A deck is needed for the warping windlass and to provide a place in the bow to carry wood for fuel. So, lengthen the boat to the left by about a quarter-to-a-third of its current size. Make this the bow, put a deck with a large spool on it for the windlass; and run a drive shaft or chain from the windlass back to the flywheel end of the engine.

• A stern large enough for a rudder and a steersman, and for the "engineer" who operated the steam engine, is also needed. So, lengthen the boat by about the same quarter-to-a-third of its current size to the right; make that the stern and mount a rudder or, more probably, a steering oar from it.

• And finally, reverse the direction of the smoke flowing from the stack; i.e. make it go to the right as "our boat" moves forward to the left. Got the "picture"?

Figure 5. Artist's Sketch of Evans' 1804 Amphibious Dredge.

Improvements to Falls and Rapids, and Warping Through -

By the end of 1812 the situation was this: Sullivan had a towboat in which he had invested heavily (apparently more than $5000 for this boat, alone, plus all the development that preceded it); in addition to its chain-floats drives, this boat incorporated a warping windlass to which the power of the engine could be directed; and four rapids remained improved, but not yet canalized. Keep in mind that this was a very expensive, one-of-a-kind towboat, and Sullivan would not have exposed it to unnecessary risk.

There are several references that state which falls and rapids were improved (Wicasee, Taylor's, Hill's (aka Hill's Crossing) and Cromwell's); when (in 1811); and the amount of money expended. No documentation has been found to describe the engineering and construction done under the title of "improvements". However, physical remains at several sites do suggest what these improvements likely consisted of.24

What physical and procedural model could one build to meet these bounding conditions? Figure 6, following, illustrates the author's concept for such a model (described in italics).

Figure 6. 'Improvements', and Warping Through Improved Falls and Rapids (Author's concept.)

Reference the small letters at the top of the drawing; these portray, sequentially, what was done to a falls or rapid, and how the "improvements"may have been employed. (Note: the river "flows" from top to bottom of the diagram.)

Improvements probably involved - first surveying rapids (the "belt" of heavier diamond-shaped glyphs in the middle of the figure) to determine where a path could be created through them.

• As depicted in (a), rocks and boulders would be removed to clear a path; and gunpowder (dynamite had not yet been invented) might be used to widen and/or to smooth the bottom of the channel. (the cleared passages designated by "v" shaped glyphs between the diamond glyphs).

• A timber crib wing dam, or dams, (the "fish scale" glyphs within black-bordered rectangles) was/were constructed to create a slack water pool and to divert at least a portion of the river's flow into the channel, to ensure a reliable flume.

• Perhaps unique to the Merrimack, an anchor point, probably of heavy timber crib construction (also fish scale glyphs within black-borders at the top of the figure, along side the letter references), was built 100 yards or so upstream of the top of the rapids. To this, a long, stout rope, i.e., a "warp line", was attached. This rope would be long enough to reach - to the rapid, down the rapid, and into the quieter water beyond.

• Finally, a float (the "barrel-shaped" glyphs) would be attached to the loose end of this line.

Descending through the flume within a rapid simply required a crew to maneuver a boat, or raft, or "band of rafts", so that it aligned with the channel center, before allowing it to pass down through.

But when traveling upstream, i.e., ascending up through the flume within the falls or rapid could be quite difficult The heavy rope, noted above, enabled boats to warp their way up; that is to draw themselves up along this line, which was firmly anchored above the falls or rapids.

To warp the steam towboat up the rapids, the procedure would have been as follows, starting at (b).

• The towboat would "steam" up to the float where the end of the warp line would be grappled, hauled aboard, wrapped a few times around the windlass, and pulled tight, thereby stretching the entire line taut all the way to the anchor point.

• With the towboat now safely tethered by this line to the anchor point above the rapids, as shown in (c), the power of its steam engine would be cut and mechanically shifted from the chain-floats drives to the windlass.

• By then applying the power of its steam engine to the towboat's "warping windlass", as shown in (d), the boat would be pulled along this line, i.e., the boat would warp itself up the rapid.

• When the boat neared the anchor point, still firmly attached to it by the warp line, as shown in (e), the engine power would again be cut, and mechanically shifted back from the windlass to the chain-floats drives.

• Once power was applied and the boat began moving forward, as shown in (f), the warp line would be slacked; at which time it would be cast off from the windlass and the boat would proceed up river to the next rapid. This procedure would be repeated at each improved rapid.

Sullivan must have spent 1813 refining this boat, having the river structures built and/or strengthened from which to anchor the warp lines, and working out the procedures to safely and reliably accomplish the maneuvers described above.

In 1814 Sullivan was able to get his freight boats all the way up river to Concord, New Hampshire, though not with scheduled reliability. By late 1815, however, he was able to establish regularly scheduled service between Boston (MA) and Concord (NH).

Since construction of the last of the canals was not completed until late that same year, and two rapids (Hill's and Taylor's) never were canalized, it appears that the warping windlass enabled Sullivan to begin long distance shipping about two years sooner than he would have been able to if he had waited for all of the canals to open.

The First Towboat Patent -

The towboat patent was the object of a dispute between Sullivan and Robert Fulton, who attempted to lay claim to Sullivan's concept and development work as his own.25

Through an intermediary, Swan (possibly Samuel Swan, clerk for the MCC), Fulton solicited information about Sullivan's concept for a steam towboat, i.e., a powered boat able to tow other unpowered vessels. Swan told Sullivan of Fulton's interest and Sullivan answered Fulton directly, providing the information he requested. Fulton, in turn, prepared and submitted a patent application based upon the information he obtained from Sullivan.

A short time later, Sullivan also submitted a patent application for the same concept. By law, an arbitration was conducted to resolve the dispute.26

James Munroe, then Secretary of State, appointed the Honorable James Hillhouse, Esq., as chairman. The two parties named Eli Whitney (Fulton) and Theodore Dwight (Sullivan), Esqs., as arbitrators. Initially, they met in Hartford, Connecticut, on November 30, 1813. Several months later, they met again in New Haven and, at that meeting, unanimously voted to award the towboat patent to Sullivan. No copy of the patent has been found, but the title read "Steam Tow Boat and Warping Windlass", It was dated April 2, 1814.

The deciding factors in that decision were that:

"after many experiments and much expense [Sullivan] succeeded in adapting steam engines, of a peculiar construction, to boats of the small burden used on our canals and rivers, so as to enable a steam boat of this size to contain a power of twenty or thirty horses, and to tow a number of luggage boats, and to overcome rapids by the same power applied to a windlass connected with the engine. -- Your petitioner now owns such a boat, and put the same in operation on the Merrimack river the last year;"27

— and that he had sold a similar boat to the US Navy.

Boston Navy Yard Towboat -

There is an oral tradition that the date on a bill of sale for a similar boat sold to the Boston Navy Yard influenced the decision of the arbitrators in the award of the 1814 towboat patent to Sullivan, as described above. This is somewhat reinforced by evidence that Sullivan purchased at least two engines from Oliver Evans, and the fate of the second engine is not otherwise known.

But beyond sketchy evidence that it existed and likely used an Evans' engine, no information has yet been found to describe the configuration of this boat or to confirm its role in the dispute with Robert Fulton. It seems likely that it would have been a near replica of the river tow boat, likely also using chain-floats drives. If it, too, had the warping windlass, very likely the ship yard would have used it quite differently than it was used on the river.

FOURTH GENERATION TOWBOAT -

1816 Information about this boat is sparse. The descriptions to follow are pieced together from multiple vague sources.

A Major Revision -

Several historical papers claim that, in 1816, a side-wheel steamer began operating on the Merrimack River.28 It was described as "having a sharp bow, similar to but not so sharp as steamers at present [1877], and a stern slanting up from the water like the river boats of the present day, with two paddle wheels, one on each side". Likely this was a new hull fitted out with extensively modified components of Evan's engine from the 1812 boat, to alter the action of the engine from vertical to horizontal, and equipped with simpler paddle wheels in place of the chain floats drive (though possibly at the cost of paying a royalty to the estate of Robert Fulton, who would have held Fulton's patent on side-mounted paddle wheels).

In an 1818 letter, Sullivan offered only a few words to describe the 1816 boat: "I was from these circumstances obliged to suspend my operations on the Merrimack [in 1815] until I should contrive or procure a horizontal action of the engine. In this I have succeeded."29

The improvement may not have come without difficulty. In a letter to Samuel Morey, Sullivan told of a steam engine model that was ready for trial the previous month. He stated: "The steam rose rapidly and high. The engine made about thirty strokes while unattached to any appliance. The 2nd day it carried the paddle wheel & machinery, but too feebly for work, the boat was not in the water. It worked so feebly that I was unwilling to risk its reputation without some improvements."30

Sullivan was preparing an air pump and condenser, and he hoped, by the end of the month, his communication might be more agreeable. The engineer had not yet finished the plate of the wheel but it would soon be done. ".... everything in this world takes time," he wrote.

It seems undeniable that the new engine worked horizontally, but how was it configured and what did it look like?

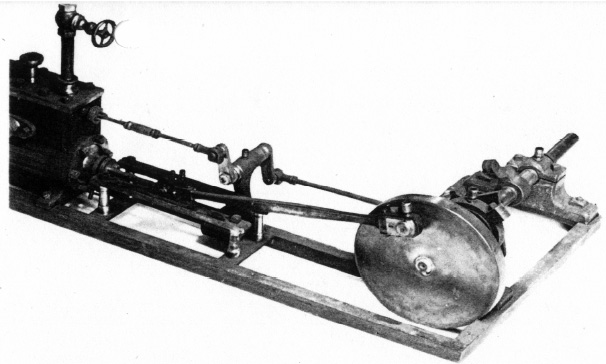

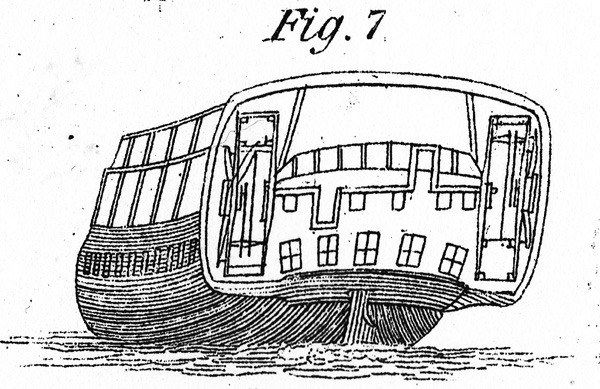

By 1815, Samuel Morey and Sullivan were collaborating. Among Morey's surviving memorabilia, there is an 1826 patent model of the horizontal steam engine shown in Figure 7.31

Figure 7. Patent Model - Horizontal Engine of Morey's Design

The configuration of this engine is very similar to what became standard on railroad steam locomotives decades later and, scaled up to a larger size, something of this nature is certainly a candidate for the type of engine Sullivan described.

In the same 1818 statement, noted several paragraphs above, Sullivan went on to say: "- yet I am better satisfied with the rotary engine invented by Samuel Morey, Esq., whose patent I have purchased for navigation. An engine of this kind has lately been erected at the navy yard in Charlestown, which carries a saw 120 strokes a minute."32

The rotary engine is what Sullivan intended to use to power a future towboat, but he was not yet ready to do so in 1816, at the time that he relaunched his greatly modified 1812 boat.

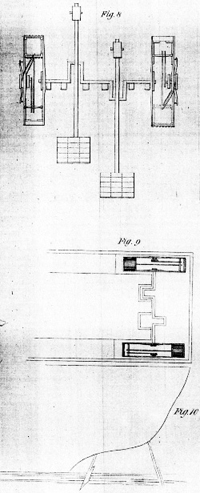

Regarding the paddle wheels that were employed, there is an additional clue that might possibly relate. In the 1930s, Leon Cutler photographed most of the remains of the Middlesex Canal. Among his collection of glass slides is the photo shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Paddle Wheel, Steering Oar and Related Items from a Merrimack River Steamboat.

The oral tradition is that this wheel came from a canal related steamboat. Well before the mid-1800s the supporting structure of most paddle wheels was made of iron, but this wheel is of wood. And, as will shortly be apparent, this is not the configuration Sullivan used on his later boats.

Clearly, this is not a flywheel. Notice the four "ears", outboard of the rim at the ends of each of the spokes. These appear to be component parts of the wheel and may have been the support structure for the individual "floats" ("paddles" as we'd now call them).

Could this be a paddle wheel from the 1816 boat? No other candidates have been identified, nor have any other uses for a wheel of this configuration been suggested.

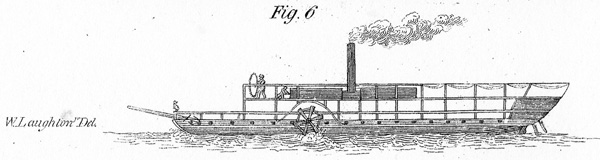

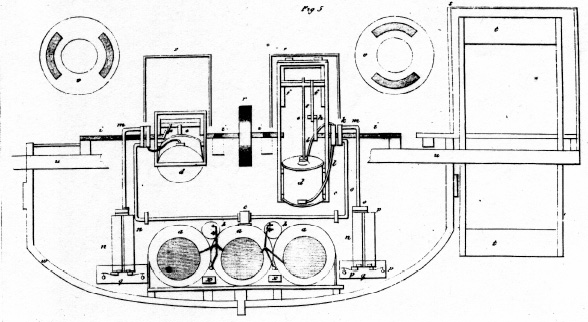

FIFTH GENERATION TOWBOAT - 1818

The Merrimack -

If the 1812 boat was Sullivan's most interesting, this 1818 boat was, clearly, the most powerful, technologically advanced and successful. It was 65 feet long, 9 feet wide at the bow and 7 feet at the stern. It had two boilers, each consisting of two cylinders, one within the other, the outer about 3½ feet in diameter and 15 feet long; the inner cylinder being about half the diameter of the outer and inside of which the burners were placed. The boiler was fired using an alternative fuel, likely tar (from trees, not petroleum), but possibly also rosin or turpentine.

Designed by Samuel Morey, the engine was a rotary type, hung on two journals.33 The cylinder, piston, cross-head, and the frame enclosing them, all rotated around a stationary crankshaft. The rotating components were connected by a drive-shaft that ran to a wheel at the stern, bevel gears uniting it to the shaft of the stern wheel.34 It was simple to operate and significantly reduced internal power losses.

|

| Photo by the author Access to the Model compliments of the Vermont Historical Society |

| Figure 9. Morey's Rotary Engine Design, sequence of rotation |

The Vermont Historical Society's museum owns the "feasibility demonstrator" for Morey's rotary (or rotating) engine. Essentially it is a rudimentary single-cylinder engine mounted on a large tea kettle size boiler, with a rotary steam valve in between. This model was something that Morey could place on his cook stove to verify his concept for its operation. Figure 9 shows eight successive views of this engine, with the engine rotated 1/8th of a turn from each preceding photo.

The boat employed a large double stern-wheel (the subject of a December 1818 patent), gear-driven by the drive-shaft connected directly to the rotary engine.35

|

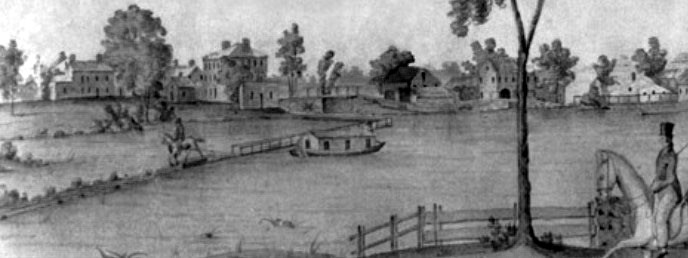

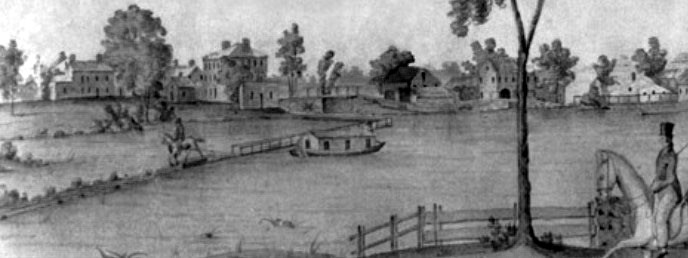

| Plate compliments of the Medford Historical Society |

| Figure 10. Canal Aqueduct at Medford, and Steamboat Merrimack, 1818 |

In a historical research paper prepared for the Medford (MA) Historical Society, historian Moses Wichter Mann included a sketch of a boat in a plate that accompanied his article.36 The sketch is shown in Figure 10. The configuration of this boat corresponds very closely, with the drawings shown in Figure 11; almost certainly they all refer to the same boat. Mann indicated that this boat began operation in 1818, and an inscription on a glass slide of the original sketch bears the date "August, 1818".

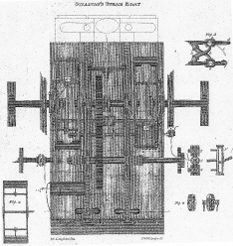

Figure 11. the Merrimack, Side and Top Views

This boat provided a significant improvement in performance. Sullivan stated "that the same boilers which once carried a twenty horse engine of Evans' in my first steam tow-boat, that could not be made to tow more than one boat, now applied to a small single revolving engine, can tow four boats faster than the one was carried and consume not half so much fuel."37

Unlike the earlier boats, information about this one has survived. Figure 11 is a (not quite to scale) line drawing of its side and top views.

Regarding this figure, the forward structure appears to be a reservoir or tank, likely a fuel tank for the storage of the tar or whatever other fuel the boat used. This assumes that water for steam was drawn directly from the river, a fairly standard practice with boats operating on fresh water rivers. Both the port and line for drawing water from the river can be seen between the boiler and the engine, to the left of the stack ducts.

The boiler is located immediately to the right of the fuel tank/reservoir. The boat used two boilers, side by side, to produce the steam to power the engine. These were fueled from the front and the heat of combustion was conveyed through the boiler in one or more tubes; Morey patented the concept of a three-tube boiler at about this time, and this boat may have employed this innovation.

Though not shown, the exhaust stack was mounted to the rear of the boiler, the rectangles with ovals may be ducts to the stack. Likely a water pump, and possibly a condenser pump, are also located close by.

Notice the small box above and near the front of the boilers. This is the main component of Samuel Morey's patented "American Water Burner". Alternative fuel (tar?) and exhaust steam were both fed into the box. The box contained a maze of baffles that forced the fuel and the exhaust steam back and forth as it progressed forward from the stern end. Along the way the fuel combined with the steam, was "gassified" and dissociated, and the resulting hydrocarbon was fed into the boiler to be burned.38 Claims were made that this resulted in very clean burns, with little visible smoke emitting from the stack.

The engine is mounted immediately behind the boiler. Unique to this boat, the engine is a single-cylinder Morey rotary (all other known Morey rotaries were of two orthogonal cylinder configurations).

In this engine, the crankshaft is fixed to the boat, and it is the complete piston and cylinder assembly that rotates around it. This arrangement allowed the connecting rod to be kept rigid, thereby transferring the maximum of engine power while minimizing internal engine losses.

One end of a drive shaft is connected directly to the engine. A bevel-gear, attached to the opposite end, mates with another bevel gear attached to the common shaft on which the two stern wheels are attached. (This is the subject of the Dec 1818 patent for the Double Stern Wheel).

Twisting History -

Sullivan was proud of this boat. He christened it the Merrimack and, in July 1819, he took it up river to Concord New Hampshire. For two weeks, he demonstrated it to townsfolk and dignitaries alike. The Merrimack towed several other boats, decked out with canopies and bunting, with at least one carrying a brass band. Anyone who wanted a ride, got one, along with the best entertainment available.

But Sullivan never took the boat back to Concord again, leading early New Hampshire historians to conclude that the use of steam on the Merrimack River, and this boat in particular, were failures.

Of further historical interest, locally, this boat is rarely referred to as Sullivan's finest achievement or as the Merrimack Boating Company's towboat. In a Lowell newspaper article, and several other historical papers, it is identified as the Boston and Concord Boating Company's (B&CBC) steam boat.39 At this, one must ask - how long would the B&CBC have had to operate this boat for it to be noticed and written up by the news media of a city that didn't yet exist in 1823, the year the B&CBC company acquired the boat?

Clearly, steam was not abandoned in 1820. But why are these boats so little known? Examination of Figure 12, a map of the Merrimack River, and a plot of the locations of the canals along it, suggests a possible answer.

Figure 12. Plot: Merrimack River Canals & Improved Falls

In the first 25 miles north from the head of the Middlesex Canal, there are only two single-lock canals, at least one of which did not charge a locking fee for passing an empty boat through. Would the Merrimack have been considered an empty boat? Definitely "yes" for the Wicasee Canal and probably "yes" at Cromwell's too. But, in the 10 miles north from the base of Moor's Falls, in upper Litchfield, New Hampshire, there are seven canals with a total of 14 locks (initially 16, until 1816 when the Amoskeig Canal replaced Blodgett's Canal). In the last 15 miles there are two canals with a total of seven locks. All of these charged to lock an empty boat through.

Consider that when operating with a towboat, it and each of the "luggage boats" in tow would have been locked through individually, with each paying a lockage fee. Thus, there would have been "high payoff, low cost" in operating over the first 25 miles; then "high cost, low payoff" over the next 10 miles; and finally, "moderate payoff, moderate cost" to operate over the final 15 miles.

All of this suggests that Sullivan may well have operated his towboats over the first 25 miles of the river, only, and allowed his "luggage boat" (freighter) crews to proceed on - poling, rowing and/or sailing - as all other boatmen did, over the final 25 miles. He may also have operated the freight boats over the first 25 miles using a reduced crew, i.e., picking up (or dropping) crew at the base of Moor's Falls Canal for the remainder of the trip north.

That these boats were towboats, not passenger carrying "packets", and that they only towed freight boats, not packets, further insured that they operated over the years in relative obscurity.

The Coastal Steamer Experiment -

In July, 1818, the Hartford Courant announced: "We have the pleasure to announce, that the Hartford Steam Boat, with the revolving engine, built by the Connecticut Company, made her first movement on Friday last -- and went at the rate of six miles an hour, notwithstanding the wood used was not seasoned. The gas fire made from tar, was found a very useful auxiliary. We understand she will shortly be in readiness to take passengers to the sea coast".

In the same year, in November 1818, Sullivan and his associates launched a new boat on the lower Connecticut River. A Hartford newspaper stated: "Last week was launched from the ship-yard in this City, the first steam-boat ever built on Connecticut River. It is designed for a tow boat to ply between this City and the mouth of the River."40

(Thus, it is not entirely clear if the foregoing refer to one steamboat or two. Until proven otherwise, the assumption is that both articles refer to the same boat.)

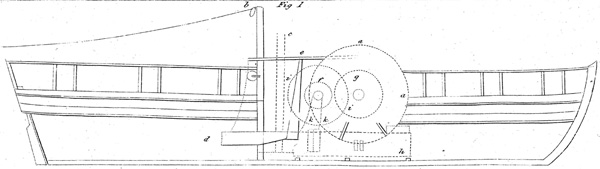

Figure 13. possibly the Coastal Steamer Experiment

Named the Experiment, this boat was actually an ambitious attempt to build a coastal steamer capable of operating between Connecticut and New York Harbor,41 thus it would have been considerably larger than the boats built for the Merrimack.

Figure 13, which appears in Professor Silliman's Journal …, may be a top-level drawing of this boat, though Sullivan never specifically identified it as such. If so, the boat was a side-wheeler, with the paddle wheels placed forward of the center of the hull. Note that the boiler is located at a deck-level above that of the boat's main deck.

Likewise, the drawings shown in Figure 14 may be of the engine used in this boat, though they too are never so identified. But that one of Sullivan's comments about this engine was that it "should be turned on its head" further reinforces its association with the boat in figure 13.

Figure 14. Large Morey Rotary Steam Engine, Boilers and Control Provisions;

Front & Top Views; possibly for the Coastal Steamer Experiment

Regrettably there is no scale on the plate, nor is this engine discussed in any correspondence yet discovered; and so there is no way to tell just how much larger this engine may have been, only that it was more refined and complex. It also seems to be more heavily built than any others yet seen.

It seems plausible, even probable, that this engine was destined for a large boat, perhaps of the size Sullivan envisioned for coastal travel.

In late 1822 and early 1823, this boat was tauntingly cited in a particularly scathing public exchange between Sullivan and Cadwallader Colden, Robert Fulton's apologist and defender of Fulton and Livingston's monopoly for the use of Fire and Steam on New York waters. Colden acerbically stated:

"About the year 1819 you constructed a steam boat on Connecticut River. We may presume she had all the advantage of your sixteen patented improvements, yet she was perfectly innavigable. Why was she a dead loss to all who your representations had induced to take a concern in her. After some attempts to run between Hartford and Saybrook this patented towing vessel was found incapable of moving even herself against the slight current of the Connecticut River, she was towed to New York where she was sold, with all your patented improvements, for no more than the value of her hull. She was purchased by Captain Bunker. Every part of your new invented machinery was sold for old iron. Such machinery as is in use in boats of Fulton and Livingston was put in her, and she now, with a success equal to that of any other boat, navigates the waters of this state under the name Enterprise."42

Sullivan acknowledged that the Experiment never exceeded six knots, but claimed that it needed only an increase in boiler capacity for it to do so.

Regrettably, Sullivan and his proprietors were unable to obtain authorization from the New York Legislature to operate in New York waters, though a favorable resolution was passed by that state's Senate to allow them to do so. As a consequence of poor performance and legal obstructions, the proprietors became discouraged. After a season of plying the Connecticut River, between Saybrook and Hartford, the boat was laid up and the decision was made to sell it. Before doing so, however, Sullivan repurchased the principal part of the rights to the engine from his partners. (Did he then have the engine removed?)

The embarrassment of failure may account for Sullivan's reticence to say much about this boat in his correspondence with Professor Silliman, while pride in what he had almost accomplished may have compelled him to at least insert basic drawings associated with the effort.

Sullivan's Enterprise -

The following year, in 1819, Sullivan launched a second steam towboat on the Connecticut River. Built at Hartford and (also) named Enterprise, this boat was also a "side-wheeler" intended for use as a tow boat in tidal waters. This boat was of Sullivan's intermediate size, larger than the Merrimack but considerably smaller than that required for coastal travel. It employed a 100 hp Morey rotary engine.

And a week later, in the Hartford Times: "The Steam Boat Enterprise, of Hartford, on Friday last, made a trip to Middletown. The machinery of this boat is the patented revolving engine - the first that has been made on a large scale. It works admirably, with a steady equable motion; without any jarring effect, and with as little noise as is possible, in a machine of this magnitude."43

In correspondence with Professor Silliman, published by him in the Journal of American Science and Art in 1820, Sullivan included a guide to the plates he had provided the preceding year. In it he stated that this boat was "seventy-seven feet long, twenty-one feet wide, and measures one hundred and thirty-six tons. The engine, with its boilers, ... occupy sixteen feet by twelve, or one-eighth only of the boat; the cylinders being hung on the timbers of the deck over the boilers. She is principally intended to tow vessels up the river to Hartford."44

A side view of the Enterprise is shown in Figure 15. In the drawing, the larger circles represents the size and location of the side-mounted paddle wheels. The smaller circles show the location of the engine. Note that, as Sullivan described, the boilers are at the bottom of the hull, positioned under the engine and drive assembly.

Figure 15. Side View of the Towboat Enterprise

Also shown in this drawing is a structure mounted externally, immediately behind the starboard paddle wheel and no doubt replicated on the port side as well. This is a mid-ship rudder most likely the subject of the Dec. 1818 patent for "Steam Boat Side Rudders".45 In the 1819 correspondence with Silliman, Sullivan went on to explain the purpose of these "… as the boat herself, at the moment of commencing the operation, may have no steerage-way, by placing two blade rudders at the side, behind the water-wheel, where a current is occasioned by them, the boat is kept in her relative position."46

The configuration of this boat's engine is shown in Figure 16. In this figure, only one paddle wheel is shown, the one on the left is implied.

Figure 16. Front View, Morey Rotary Engine for Towboat Enterprise

The engine is a two cylinder rotary of Samuel Morey's design. Note that the two cylinders are mounted orthogonally, so that one cylinder provides full power while the other exhausts and recharges steam.

For this boat, Sullivan used three boilers with interconnecting distribution pipes to equalize the steam pressure among the three. Also shown, mounted above and between the boilers, are two smaller diameter cylinders. These are referred to as "tar vessles", appear to be a variant on Morey's "American Water Burner" and thus perform tar (fuel) "gassification". The vertical cylinders, to the left and right of the boilers are the condensers, which "collapse" exhaust steam and thus create a vacuum on the back side of the pistons, thereby adding to the power of the engine.

The two unconnected disks, at the top of the drawing, show the arrangement of the rotary valves that were used to admit steam into the cylinder to begin a power stroke and, simultaneously, to exhaust steam from the opposite side of the piston. That the slots are left and right in the left disk, and top and bottom in the right disk, correspond to the orthogonal layout of the cylinders.

Where did it go? -

This boat appeared on the Connecticut River for only a very short time, perhaps a month or so, then it disappeared. But around the time of its disappearance, a boat of the same name appeared in Georgia.

Evidence suggests that this is the boat that Sullivan took to Georgia, to be used in a successful effort to establish a shipping company to operate on the Savannah River and its tributaries.

Sullivan sold his interest in this company for $5000, and returned to Boston.

THE BOSTON STEAMBOAT COMPANY

On June 15, 1821, The Massachusetts Legislature incorporated the Boston Steam Boat Company "… for the purpose of constructing steam boats, and the machinery appertaining to them, in the towns of Medford and Boston, and of vending or using the same; and for this purpose shall have all the powers and privileges, and be subject to all the duties and restrictions … ."47

Sullivan bought a half interest in the old Symmes mill privilege on the Aberjona River. With his partner, Captain John Symmes, they built a second mill across the river to grind corn. As Captain Symmes was a wheelwright, the old mill contained a lathe and a trip hammer. This was the scene for Sullivan's development and production of Morey-designed steam engines. Sullivan later bought out Symmes interest, but in about 1823 misfortunes with his various enterprises bankrupted him and he sold the mills.48

The Patent -

At least the Patent's hull, and perhaps the entire boat, was built in Medford, Massachusetts, by Thatcher Magoun's shipbuilding company. It was listed as a steamer of 98 tons displacement and its owners were J. S. [sic] Sullivan and Richard D. Tucker.49 (This is the only one of Sullivan's river tow boats for which the builder is currently known.)

Sullivan stated, "late in 1821, we sailed from Boston to Charleston, South Carolina, in the little steamer Patent, to form a company for the navigation by tugboats of the Santee River." We "… arrived, ascended [the Santee River, and] fulfilled expectations practically…. The "engine" towed loads of merchandise up the Santee against heavy freshets, bringing down cotton on the return trip."50

But this enterprise suffered a serious setback.51 A lock fell in on the Cooper and Santee Canal, blocking the canal and forcing the Patent to make a circuit of the seacoast to get from the river's mouth to the port of Charleston. This stroke of misfortune was followed by the bursting of a boiler when the boat grounded on a sandbar in the Santee River.

A human tragedy may have accompanied this event. According to southern records, mechanic Daniel Dod died May 9, 1823, having been severely burned in the explosion of a boiler on the Patent, machinery he had been repairing while making a trial trip on the East River.

This enterprise was closed at a loss and Sullivan returned north.

Aside from its displacement, no documentation has been found to describe the size and configuration of this boat. But, if the collapse of a lock forced a change in routing, then the Patent must have been using the locks of the Cooper and Santee Canal. Typically, these locks were 10' x 60', about the same width as those on the Merrimack River, though shorter by a quarter. This suggests that the Patent may well have been a near replica of the steam towboat Merrimack in both size and configuration.

Other Innovations - a Submarine - ??

Among Sullivan's patents there are two that are unexplained in any documentation or correspondence found thus far. But taken together, they open an intriguing question.

These were both issued in March of 1817 and are, respectively, "Propelling Boats By Compressed Air" and "Submarine Propeller".

There is an oral tradition that Sullivan sold a towboat to the Boston Navy Yard in about 1813. If so, he likely had some constructive intercourse with the Navy. So, was Sullivan working on the design for a submarine? The patent titles suggest this possibility!

Figure 17. Stern of a Ship Propelled by Paddles |

Figure 18. Patent Concept, Using Paddles to Propel Ships |

Propelling Boats with Paddles -

In the boat in figure 17, the cylinders of the Morey Rotary Engine are arrayed on opposite sides of the stern, and connected by something that appears to be a crankshaft. Likely, this was the graphic component of Sullivan's April 1818 patent application entitled "Paddles for Propelling Ships". Another plate, shown in Figure 18, provides related detail.

In the sketch following, the two piston-cylinder assemblies of a Morey Rotary Engine are separated the same as is shown in the stern of the boat. But here, the interconnecting crank shaft is shown to operate on two vertically hung paddles. (This is not the engine's crankshaft, it corresponds, instead, to the Merrimack's drive shaft.)

Each of the paddles moves within a retainer (not shown) at the top that allows them to both pivot through an arc and slide vertically. The action of the engine, therefore will lower the blade of the paddle, sweep it through an arc to propel the boat forward, and then raise and recycle it, as shown in the lower sketch.

This appears to have been yet another concept to avoid the use of side wheels, and thereby to avoid paying a royalty to Robert Fulton. Sullivan's intent may also have been to contain the engine and drive system within the dimensions of the boat's hull, thereby eliminating sidewheels that typically extended out on both sides of the boat.

Research Notes52

Research into Sullivan's shipping and towboat development efforts have long been hampered by a dearth of corporate records. Only the records of the Middlesex Canal Company have survived; no records of the Merrimack, Union or Boston and Concord Boating Companies, or the Boston Steamboat Company, have yet been found. Thus, histories to date have presented a Middlesex Canal-centric view of all related activities.