Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 63 No. 2 | February 2025 |

The Summit Pond on the Concord River in North Billerica is shown here in a 2023 photograph by Marlies Henderson.

To the left can be seen the former Talbot Mill warehouse which when completed will be the site of the MCA’s Middlesex Canal Museum.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MCA Sponsored Events and Directions to the MCA Museum and Visitors’ Center

President’s Message: “Summit Pond of the Middlesex Canal” – by J. Breen

What’s happening at our New Museum on the Summit Pond? – by Betty Bigwood

A Note of Thanks – by Russ Silva, Treasurer

“Troubadour Paul Wiggin” – by Betty Bigwood

“River in the Sky” by Douglas P. Adams (reprinted)

Editors’ Letter

Hello Readers!

Welcome to 2025, the Year of the Snake, and hopefully the year the Middlesex Canal Museum opens at the new location visible on the cover photograph.

The highlight of this issue is the continuation of Douglas Adams’ history “River in the Sky.” We hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

Betty Bigwood has submitted a tribute to Paul Wiggin, a much-loved member of the MCA and part of the quartet that sang Dave Dettinger’s wonderful canal song. Pictures are included.

Lastly, the President’s Letter about the mill pond and dam, the schedule of events through to October, and the directions and disclaimers round out the issue.

Please remember that we are always looking for new submissions to Towpath Topics from members and friends.

Your Editors

MCA Sponsored Events – 2025 Schedule

Winter Meeting: 1:00pm, Sunday, April 6, 2025

“The Concord River: Life of a River Herring”

Speaker: Ben Gahagan

Location: Reardon Room, Middlesex Canal Museum,

71Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862

Ben Gahagan at the Centennial Dam fish passage on the Concord River in Lowell, MA

Middlesex Canal Commission Annual Meeting:

3:15pm, Thursday, March 20, 2025

Location to be Announced, Date Tentative

Spring Walk: 1:30pm, Sunday, March 23, 2025

Billerica South to the Smallpox Cemetery

Meet at Billerica Falls, 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica

Winter Meeting: The (delayed) MCA Winter Meeting will be held on Sunday, April 6, 2025 at 1:00pm in The Reardon Room of the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor’s Center at 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862. The talk will examine the importance of alewife and blueback herring, including life history, food web dynamics, and fisheries. In addition, the speaker will focus on restoration strategies and lessons learned over the past 30 years.

Ben Gahagan, the speaker, is a biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. He has twenty years of experience and is an expert in the biology and ecology of the river herring and American shad.

The talk will be preceded by a five-minute MCA business meeting. The free museum will be open from noon until 4:00pm.

Bike Tour South: 11:15am, Saturday, April 19, 2025

Meet at the Lowell Train Station. Leaders: Dick Bauer and Bill Kuttner.

The 11:15am time will change with the MBTA Lowell Line Schedule

Annual Meeting: 1:00pm, Sunday, May 18, 2025

Speaker and Location TBA

23rd Fall Bike Tour: 9:00am, Sunday, October 5, 2025

Meet at the Middlesex Canal plaque right at the entrance to the

Sullivan Square T Station, 1 Cambridge Street, Charlestown, MA 02129.

Leaders: Dick Bauer and Bill Kuttner.

Fall Walk: 1:30pm, Sunday, October 19, 2025

Maple Meadow Aqueduct.

Meet at kiosk, 35 Towpath Drive, Wilmington, MA 01887.

Fall Meeting: 1:30pm, Sunday, October 26, 2025

Speaker and location TBA.

For more information on the Spring and Fall Walks, our Bike Tours, and our meetings, please access the MCA website, www.middlesexcanal.org.

The Visitors Center/Museum is open Saturday and Sunday, Noon – 4:00pm, except on a holiday.

The Board of Directors meets the 1st Wednesday of each month, 3:30-5:30pm, except July and August.

Check the MCA website for updated information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Directions to Museum: 71 Faulkner Street in North Billerica, MA

By Car

From Rte. 128/95

Take Route 3 (Northwest Expressway) toward Nashua, to Exit 78 (formerly Exit 28) “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at the fork. After another ¼ mile, at the traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A (Boston Road). Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road (Talbot Avenue) which will put St. Andrew’s Church on your left. Go ¼ mile to a stop sign and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the bridge over the Concord River, where Old Elm Street becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park just beyond the bridge in the lot on your right. Watch out crossing the street!

From I-495

Take Exit 91 (formerly Exit 37) North Billerica, then south roughly 2 plus miles to the stop sign at Mt. Pleasant Street, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700’ and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street (Faulkner Street). To get to the Visitor Center/Museum enter through the center door of the Faulkner Mill and proceed to the end of the hall.

By Train

The Lowell Commuter line runs between Lowell and Boston’s North Station. From the station side of the tracks at North Billerica, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station Street and Faulkner Street on the right side.

President’s Message, “Summit Pond of the Middlesex Canal”

by J. Breen

Many towns in New England have a mill pond. Billerica has a summit pond. The agreement between the Middlesex Canal Company and Francis Faulkner, the mill owner, recorded May 5, 1825 in the now Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, book 260, pp. 48-53, authorizes Faulkner to draw the pond down to the top of the flash boards, but if he draws down from the top 3/4” or more, he will pay a fine.

The summit pond and dam are on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Middlesex Canal. “The Middlesex canal, uniting the waters of [the Merrimack River] with the harbor of Boston, is however the greatest work of the kind which has been completed in the United States.” Report on Public Roads and Canals by the US Secretary of the Treasury to Congress, April 4, 1808. Retrieved from the internet, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2046. The National Oceanography and Aeronautics Administration (NOAA) has suggested that a plaque be used in place of the dam as was done in Exeter, NH.

More significantly, the summit pond and dam are part of the Town’s Billerica Mills Historic District. The bylaw for the Historic Districts Commission states that “no demolition permit for demolition or removal of a building or structure within an historic district shall be issued by any Town department until the certificate required by this section has been issued by the Commission.

Section 7, https://www.town.billerica.ma.us/DocumentCenter/View/8358/historic_districts_by-laws_201403071038124105.

The bylaw authorizes three certificates as follows:

(1) Appropriateness. At the most recent inspection of the dam, the engineers summarized their report, a 121-page PDF, “In general, the Talbot Mills Dam was found to be in fair condition primarily due to the lack of any operation or maintenance plan. Executive Summary, page 1 (2-121pdf), Geotechnical Consultants, Inc, Talbot Mills Dam Inspection, April 30, 2021. No reason to demolish the dam. What is appropriate is a modern hybrid fishway using the rock ramp and the concrete blocked entrance to the fishway in the 1828 dam.

(2) Non-Applicability. The summit pond and dam are historic structures.

(3) Hardship. The owner of the dam is CRT Development Realty, a limited liability company, whose only asset appears to be the dam, in other words, zero liability. “Given the minimal rise in flood water downstream in the event of a dam failure, the risk of loss of life and damage to homes, industrial or commercial facilities, secondary highways or railroads is considered to be low. Additionally, flooding as a result of a dam breach to the Talbot Mills Dam is unlikely to cause interruption of use or service of relatively important facilities located downstream of the dam.” Page 9 (13-121pdf), ibid.

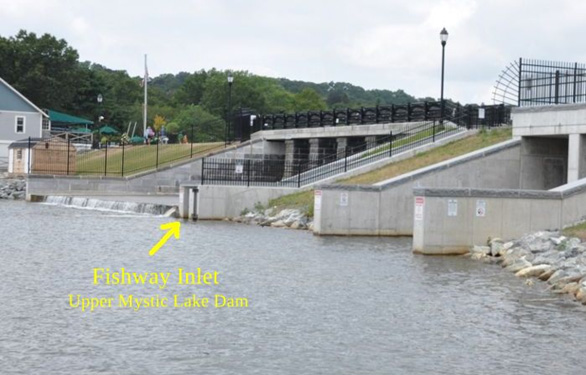

The Upper Mystic Lake Dam in Medford was renovated in 2010 with a modern fishway.

“More than 640,000 river herring passed through the fish ladder at the Mystic Lakes Dam in Medford in 2024.”

What’s happening at our New Museum on the Summit Pond?

by Betty Bigwood

It’s a cold winter day with snow on the ground and the temperature in single digits. We shut down work there as the added costs of working in inclement weather is not a frugal thing to do. Once again, beyond our control, we are delayed. Never did we ever consider that 11 years later we would still be trying to finish.

At the present time we have all the parts for the bridge construction in two blue tarp covered parcels in the parking lot. The concrete ends are complete and awaiting good weather to put it all together.

At the NW end of the museum there will be a galvanized structure upon which will sit the exterior heating apparatus. It is much more complicated than originally anticipated as there will be walkways to service the apparatus. Getting it there will require a large crane to carry it from the parking lot over the roof. Anticipated cost is $5,000. The structure designed by Rick Shaw of Shaw Welding costs $107,000. Heating will be by gas.

Along the north side will be the structure required for air exchange to operate a commercial kitchen. Fresh air must be carried into the kitchen to counter any air that is sucked out. Without a commercial kitchen label, we would not be allowed to rent out our space. We anticipate the rental income to assist paying our expenses.

Inside the building it is finally coming together. We are waiting for the platform lift to be delivered and then some final plaster work to be completed. Flooring is being discussed. The grand staircase and kitchen are being planned. The plumbing fixtures will be installed after the flooring is completed.

Meanwhile we all need a break.

A Note of Thanks

The Middlesex Canal Association’s thanks go out to the forty-five individuals who, as of Wednesday, February 5, have donated $4,485 to the 2024 Annual Appeal. This includes $1830 to the Building Fund and $145 to the Endowment Fund. The rest will be applied to Current Expenses.

The number of donors is a couple more than last year and the total amount given to the appeal is a few dollars less. But this does not include two generous donations from “Donor Advised Funds” totaling $5,500 which also arrived during the month of December.

And again, throughout the past year, one of our largest contributors donated a significant amount to the 2 Old Elm Street Museum Building renovation project directly instead of through the Appeal. Thanks to them, once more for their generosity.

If anyone else wishes to send a contribution in any amount at any time for the benefit of the Endowment Fund, The New Museum/Building Fund or the Fund for Current Expenses, please do, and thank you.

Russ Silva, treasurer

Troubadour Paul Wiggin

by Betty Bigwood

I learned of Paul Wiggin’s passing when I received an annual Appeal Letter from his daughter Margaret Wiggin for MUSE, a group of singers which Paul founded. Paul lived at the Carleton-Willard Village in Bedford, Massachusetts, with his wife who predeceased him. He died on January 16, 2024 at the age of 95.

Paul founded this group for shut in elders when it came to his attention how much their lives improved when song gave them a new lift on life.

Paul Wiggin is on the left and David Dettinger is on the far right. The partially eaten cake looks delicious!

Director David Dettinger belonged to this group of volunteer singers. David had written the five verse ballad “Haulin’ Down to Boston” as part of a ten-year program of events leading up to the anniversary of the founding of the Middlesex Canal Association. David asked Paul to sing and record the ballad which Paul did. Robert Winters put it on our website where it continues today for all to hear to brighten up their day.

Paul made several visits to our museum; to celebrate David’s Birthday and first showing of the video by Roger Hagopian on the “Canal that Bisected Boston” and to brighten up subsequent lectures. He was a kind and thoughtful gentleman who will be missed.

A copy of Paul Wiggin’s obituary from the John C. Bryant Funeral Home website, January of 2024, follows:

Paul Warren Wiggin 1/4/29 - 1/16/24 of Newton (Waban) passed away peacefully at the age of 95 in Bedford, MA. Paul and wife, Phyllis, (1/29/33 - 5/26/20) were married in 1955 and had 4 children, Margaret, Emily, Susan, and Tom, 11 grandchildren, and 1 great-granddaughter.

In the early 1950s, Paul was a paratrooper and chaplain’s assistant in the 82nd Airborne at Fort Bragg. Paul graduated from Tufts College in 1953, where he was a member of Delta Tau Delta Fraternity. He also attended Oberlin College, Longy School of Music, Andover Newton Theological School, and NE Conservatory of Music. Paul earned his Master’s in Speech Ed at Emerson College in 1969.

Paul worked in real estate, life insurance, and taught in local private schools, at Rhode Island College, at Rhode Island School of Design, and at RI Urban Ed Center.

Gifted with a beautiful tenor voice and love of singing, Paul was tenor soloist at many Greater Boston area churches, synagogues, and notable choral ensembles, most recently 25 years with The Boston Men’s Saengerfest Chorus from 1992 - 2017, performing until the age of 88.

In 1974, Paul founded MUSE Inc., a non-profit whose mission is song and friendship for shut-in elders. MUSE is celebrating its 50th anniversary, and continues its work across Eastern Massachusetts.

A second picture of the quartet, Paul Wiggin is on the left and Dave Dettinger is on the far right.

Pictures courtesy of Betty Bigwood

Editors’ Note: If you care to listen to Paul Wiggin’s rendition of the Middlesex Canal Association’s Anthem, Haulin’ Down to Boston, it can be heard at the following link:

http://middlesexcanal.org/media/HaulinDownToBoston.mp3

Editors’ Note: In the last issue we asked if any current members of the MCA recalled Douglas P. Adams, who was the President of the MCA a half-century ago. MCA Treasurer Emeritus and board member, Howard Winkler, shared his recollection of Adams’ Middlesex Canal related book entitled “River in the Sky.” In the last issue of Towpath Topics (#63-1) we published the first half of Adams’ fifty-page essay. In this issue of Towpath Topics we are pleased to publish the second and final half.

RIVER IN THE SKY: The Story of the Middlesex Canal

by Douglas P. Adams, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, M.I.T.,

President, Bay State Historical League,

Vice-President, Middlesex Canal Association

FOREIGN CANALS. SOME OTHER NEW ENGLAND CANALS - OLD AND NEW

The task of canal construction had early been mastered by King Menes, 3000 B.C., for Egyptian irrigation ditches. Tarquinius repeated the feat, draining the Roman marshes in 500 B.C. with the Cloaca Maxima. The Moors came along and built their own canals. The euphonious roster rolled on. The Chinese under Sui Yang Tee constructed the Sui Grand Canal in 609 A.D. – Kubla Khan’s grand canal in the 13th and 14th centuries – nearly 1,000 miles long. It was in fact a series of canalized rivers such as we develop today. All these flowed at constant level. Leonardo DaVinci presented designs for six locks in the canals of Milan at the end of the 15th century, while John True built the first lock canal in England in 1563. By 1680, Baron Pierre Paul Riquet de Bonrepos finished the stupendous Languedoc Canal (Canal du Midi) cleanly halving southwestern France with an unbroken silver thread from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. France eventually boasted 3,000 miles of canals.

The full potentiality of canals as a transportation device fired the imaginations of vigorous men throughout the world. Curiously, however, the English did not build canals extensively until toward the middle of the 18th century. Then, prodded and rewarded by the Industrial Revolution, they canalized the country with a vengeance. Many of these exist today, extensively used for pleasure by tourists and natives and carefully, tenderly protected from encroachment or retrenchment by an ever-growing legion of amphibians. Three different levels are occasionally to be found crisscrossing the same spot in that country. For the writer, an unforgettable English scene would always be the late afternoon shadow on the plain below of a lonely “canaler” working his way across a very long, tiny aqueduct scores of feet in the air, connecting intermountain canal levels.

The Yankee mind was addicted early and late to making moving water serve human needs. Fifteen miles up the twisting Charles River, at Dedham, the traveler is still only seven miles from salt water at the mouth of the Neponset but more important, only two miles from the nearest point on that stream. In the early 1600’s, Yankee curiosity prompted a joining canal that established conclusively a drop of six feet from the Charles to the Neponset. It diverted a flow (still running today and known as Mother Brook) potent enough to power a stout wheel but did not furnish any transportation.

Another Canal, the Fox River Canal, was intended to provide transportation from Ipswich to the shipbuilding town of Essex avoiding the killer riptides at the confluence of the Ipswich and Plum Island Rivers. A grant was made for this in 1652, another in 1682, again in 1694. Whether it fell into disuse is not too clear, but Mrs. Irene Dodge, Executive Secretary of the Wenham Historical Society, notes also that in 1820 a company was incorporated for the same half-mile canal. It then cost $1,100, on which the company continuously paid six per cent. It appears on a map published as late as 1910. It could thus serve as an “inside route” for lumber and such things bound down from the Merrimack for Essex, a good shipbuilding town. There were many other small “poling” canals.

The Blackstone Canal, connecting Worcester and Providence and presumably diverting the wealth of inner Massachusetts toward the Providence area was a traction canal chartered in 1823 and took some four years to build. The fears of professional pessimists that Boston would be reduced by this drain to a weir fishing village were diluted to some extent by the chartering of the Boston and Worcester Railroad. Still at the time the thought of a canal from Boston across the state, right through the Worcester area, was the only solution. We shall consider it later.

Unfortunately for the Blackstone Canal, it entered the race too late. It survived only seven years and was generally agreed to be the greatest debacle in the history of Providence. One of the products intended to give it great volume was coal from a certain Worcester mine that unfortunately came to be regarded as weighing less than its own ash.

The Blackstone Canal depended for water largely on sources already committed to other requirements for manufacturing. Sabotage from such competition damaged it very badly and eventually the Worcester and Providence Railroad dealt it its death blow. To this day sections of this canal continue to crop up in embarrassing places where the drainage properties of its buried course play havoc with road building operations. The Farmington Canal started at New Haven and headed for Hadley and Holyoke. Its avowed aim was to cut Hartford out of the picture of trade up and down the Connecticut by by-passing the main barrier to through transportation along that tremendous artery – the Enfield Rapids. The Hartford-New Haven rivalry was one of very long standing, stemming from the early days of their respective royal charters, and that exceeded in bitterness by none in the United States.

The early stretches of this Canal, passing through Farmington, could drain one of the richest agrarian and manufacturing regions then in existence in the United States and it profited enormously from this opportunity. When, however, it struck the long northerly reaches paralleling the Connecticut these were much less productive until the Canal tapped into the Connecticut again far across the Massachusetts line above the Hadley Falls. One interesting feature ultimately was a fast packet service that continued through the night (probably the first in the country to do this) and finally achieved the unheard-of feat of providing one-day service between New Haven and Springfield. The later Windsor Locks at Enfield and the inescapable nearby railroad eventually brought a sudden and complete demise to this picturesque undertaking.

For the public and the politicians, the appeal of the canal as a device to develop great areas can scarcely be overrated. The success of the early Middlesex spawned scheme after scheme of such magnitude as to challenge the credulity of the modern reader until he considers how far advanced canal making was in Europe at this time.

In this light, the first great Federal survey aimed at subsidizing a monumental traction canal to end all traction canals, does not seem quite so ridiculous. This was an extension of the New Haven-Hadley (Farmington) Canal all the way to the Saint Lawrence River. It planned to follow the Connecticut most of the way, assuring an abundance of water and guaranteeing navigability for the greater part of its length. It was planned eventually to enter Lake Memphremagog and fall from there to its destination in the Saint Lawrence River. The maps and plans for this colossus are strangely prophetic of Federal subsidizing a century and a half later. Fortunately, no part of this upper Canal ever got off the boards to mock the estimators of its cost.

Of more immediate urgency in the minds of Bostonians, and to many of them seemingly less speculative, was the gargantuan canal planned to cross Massachusetts that was supposed to make Boston the chief outlet for the great west in preference to New York. No less a personage than Loammi Baldwin II, of sacred lineage and proven achievement, estimated that this work would cost a mere $2,000,000. (If, however, his scheme for a northern route should not find favor, there was always that other plan advanced for a southern canal route across the state).

The northern route required no less than 220 locks for its fulfillment to the Hudson. Even at this, the spectacle of topping the Berkshires by such a continuous waterway was too much. Baldwin argued for a tunnel through them, which could not be too low down, or it would be too long. Having optimized its placement, it turned out to be almost exactly where the Hoosac tunnel is today, except that it was a couple of hundred feet lower.

The Hoosac tunnel eventually cost $10,000,000. The tunnel and canal planned by Baldwin II, would have bankrupted with lightning speed any canal company of those or considerably later years.

But the contest between canal and railroad did end easily. It swayed in the balance as new equipment became available at any one time to make one or the other victorious. With the advent of earth-moving, dredging and ditch-digging equipment, the appeal of the canal whose tonnages could be so enormous, again bargained its way into popularity. One fabulous later notion, “the inside passage,” which envisaged a waterway continuous from Boston to Corpus Christi with a ribbon of external land protection was largely realized. Much of this, as in the magnificent Carolina Sounds, has always been and presently stands available for such purposes.

The Cape Cod Canal was part of such thinking slated for this New England area. Further protection was envisaged in still another watercourse that should start from Boston, or rather Hingham, and move entirely inland to Fall River. It was alleged that this plan would not compete with the Cape Cod Canal, though the point seems tenuous. From Hingham the proposed Canal was to pass through Cohasset and Scituate heading toward the North River, whose direction of flow it reversed as it worked toward the headwaters of the Taunton River. This followed through Taunton, Berkeley, Dighton, and Somerset to Fall River, Narragansett Bay and Long Island Sound. There was a branch over to Plymouth, just in case. This waterway needed a few locks and never rose more than 60 feet above sea level. Fortunately, at the height of its popularity as an idea as late as 1907, it also failed to win sufficient support to survive.

THE BOSTON TERMINUS

The designers of the Middlesex Canal had never originally conceived that it could have a convenient Boston outlet. At the outset it was their goal that it should terminate in Medford, on the Mystic, arriving at and flowing into that river by coming down the Aberjona River and the Mystic Lakes. As it became clearer that the Canal was to become a roaring actuality, their ambitions quickened to meet the pace, and they decided they could get the water to flow all the way to Charlestown Neck. This would require running it past the Mystic Lakes higher than their level by some ten or twelve feet as well as carrying it in an aqueduct over the Mystic River above the reach of the tides. This occurred at the site of the Boston Avenue Bridge, which was later laid along the bed of the old Canal. The stone abutments and piers for that aqueduct were visible for years after the Canal closed and they supported the new bridge. After crossing the river, before entering Somerville from Medford, the Canal had a branch off to the north toward the river with a lock and a substantial terminal pool somewhat, like that at the Merrimack River end, where huge shots of timber of unrivalled quality fresh from the White Mountain fastnesses and unavailable, in volume from other parts of Massachusetts or for that matter the world, were unchained. This was the foundation of the “Medford built” ship, which pridefully bobbed in every harbor of the world.

The Medford Branch Canal was about a quarter of a mile long and lower than the general level of the Middlesex Canal, requiring a double lock entering the Mystic River (a tidal stream of varying height). Tidal locks had to point both ways, like those admitting the Mill Pond to the tidal Charles, due to the varying height of the tide and the fact that a lock gate must always point toward higher water. This Branch Canal was a separate corporation, apparently until the very end, though sharing the common demise in 1853.

On looking at the tiny Mystic River today, it is inconceivable that anything called a ship could ever have been launched there, but it should be realized that Thatcher Magoun’s first ship, Mount Aetna, was only 188 tons burden. His yards on Riverside Avenue (the north side of the stream), on the conspicuous loop of the meandering stream, are then somewhat more comprehensible as the birthplace of major ocean carriers of the times. In 33 years, he built 83 vessels whose performances in and between every port of the world were enviable indeed. Ten major American shipyards were less than a mile sway.

After Medford, the canal meandered through Somerville avoiding low places as we have seen passed directly under the present Sullivan Square terminal and immediately entered the ancient tidal mill pond created between Cambridge and Charlestown by a dam extending from the end of Mill Street, Charlestown, southwesterly to Cambridge. It was his dam that in 1775 had prevented the British sloop Falcon from covering Charlestown Neck more closely as Colonial forces moved men and supplies to Charlestown from Cambridge during the Battle of Bunker Hill. A double-gated, two-way lock in this dam permitted lockage in either direction so that canal boats could get through regardless of the relative level of tide or pond. We have observed that the Bunker Hill Tavern stood near here also, many passengers arriving by carriage from Boston (over the new bridge) at the hour appointed in the newspaper for packet departure.

There was still the problem of freighting the produce to Boston, which was the only logical market center once one had come as far as Charlestown. This involved a stretch of open water, the mouth of the Charles today but more open then, that could be very rough in bad weather. There could be no floating tow path here. A sort of floating towline was arranged, however, whereby the crew could pull and work the barge across, but which could apparently slip easily under the hulls of sailing craft. No records have been found indicating that this was not a highly satisfactory arrangement. The Boston end was at Almshouse Wharf, near the northeast corner of the North Market building at Commercial Street — at that time the water’s very edge.

This was worked in the following manner: a series of heavy anchor stones were sunk along the desired route to Boston across the open water of the Charles River and a stout cable supported by a substantial float extended upward from each one of them. Each cable had on it a strong iron ring, the rings of successive cables being joined by a chain segment to form one continuous chain from Charlestown to Boston. Apparently, each ring had a light line attaching it to the float above enabling it to be pulled upward and retrieved at any time. Thus, the main chain could be “picked up” from any cable station float if it had been lost. By pulling on the chain, the barge could be worked across the open water. Surprisingly few accounts of this procedure have survived. Under tension the rings occupied varying heights along their vertical cables, those nearest the barge riding highest and falling back to the bottom with increasing distance from it.

On the Boston side, the genius of Charles Bulfinch had just placed a stunningly beautiful new capitol building on top of Beacon Hill, or rather 150 feet from the old, top. This had raised the problem of what to do first with all the earth that had to be removed from that former towering and obdurate summit. It was decided to fill in the North (tidal power) Cove with it, whereupon the old causeway became Causeway Street, so familiar today. The pattern of the new streets was laid out by Bulfinch himself, radiating from the former head of the cove, which now became Haymarket Square. One look at the map shows the regularity of these streets and belies cow path origin.

By keeping open a lane, stoutly lined with heavy stone through this new fill and by preserving the course of the former Town Creek, a way could be had right through the heart of the city which would permit the heavily laden boats to bring their cargoes directly to the busiest part of the waterfront on the harbor at Wentworth’s Wharf. This route was by what is now known as Canal Street and Blackstone Street and ended beyond the Dock Square area at a center of shipping at that time. Slowly, however, the dock line receded still further from the shore as the eternal filling process so characteristic of the endless energies of the Bostonians. The larger ships no longer could reach the small barges, and the somewhat short-lived scheme dried up. This cut, moreover, through the heart of the city was bridged more and more extensively, then in part covered up and finally was filled in. Portions are occasionally uncovered today in digging.

However, the stretch down Canal Street was the last to succumb, being lined with heavy stone and used as a docking facility for the canal boats. Eventually, however, the Boston and Main built its tracks right over this area and hid its station in Haymarket Square, until its later withdrawal to the present Causeway Street position. Whereto from there – who knows?

Cambridge could have gotten in onto the canal scene, with its own local canals hooked into the Middlesex system. These canals, beehives of activity themselves, at that time were salt-water tidal estuaries surrounding East Cambridge with great glass works and other industries on their banks. The first Bridge had been opened connecting Boston with Charlestown in 1786. The second one, from West Boston to Cambridge, was opened in 1793. The third, the Canal Bridge (Craigie’s Bridge) was opened in 1809. The enabling act permitted Loammi Baldwin and others “the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal northwestwardly from Leverett Street in Boston to Lechmere’s point for conducting boats, rafts, floats . . . by the sides of such bridge end causeway and “could make a towing path across the land at Lechmere’s point to connect with their other towing paths.” This Cambridge system was never effectuated, but the cable and chain system described above was solely used.

THE BALDWINS AND THEIR HOME

Loammi Baldwin was a self-made engineer, a careful, persistent student, a conscientious indefatigable planner, a relentless producer. His homemade tables of trigonometric functions bear patient witness to all these qualities. His broad perspectives on engineering matters were firmly based, his penetrating details superbly documented. He had been an original conceiver of the Canal in all its generalities, vagueness and broadly assumed altitudes [attitudes?] as well as the intuitive feasibility of fingering the headwaters of the saucer like stream basins, for a practicable passage across, the several waters earlier described. He could work with contingencies and probabilities, yet accept, absorb and be bound by facts and precisions when they were revealed in all finality and stood starkly irrevocable.

Baldwin had sufficient talent for eminently sensible companionship with the mysterious mind of Count Rumford (before he boasted his title). They often walked the sixteen miles to Boston together when Rumford was attending classes at Harvard. A handsome house (still standing) was built opposite Baldwin’s for the intended use of his friend, but Rumford died expatriate.

The records of the Middlesex Canal are endless in detail and superbly documented. Its last physical trace could vanish today, and it could still be reproduced to the foot from these plans (largely because, in its later stages when ultimate success seemed certain its plans were redone by the numbered mile). Baldwin’s plans of the property takings (frequently rendered in color) were exact almost beyond need. These careful procedures minimized (to a degree unparalled in later canals) complaints that land takings were improperly done. It was unfortunate that in 1808 his differences of opinion with the other stockholders caused his permanent withdrawal from the enterprise. His death followed shortly thereafter.

In the early days of beating the bushes on behalf of better canal techniques, Baldwin had come across an apple locally called, “the peckerwood.” He liked its taste and used to serve it to assembled notables at canal occasions. It came to be given his name and the Baldwin apple to this day is a major New England winter apple. In a corner of Wilmington, atop a seven-foot square shaft, sits the only granite apple ever fashioned by man – a tribute to the one man of the race who knew a good fruit when he saw and tasted it. Local youth affectionately distributed a suitable maidenly blush on the granite to enliven its native austerity.

Baldwin sired a set of stout lads, each of whom did well in his field. Loammi Baldwin II mastered his father’s art of engineering to a degree that would have met even the high standards of that forbear. He was a primary contributor to the foundation work of the Bunker Hill Monument. He was the Chief Engineer of the first dry dock in the United States, located in the Boston Naval Shipyard at Charlestown (where it is still in use after nominal enlargement). The magnitude of this undertaking, considering the facilities of its times, is overpowering and it is one of the great American contributions to engineering and worth the trouble to visit that attend security requirements. First to be cradled was the CONSTITUTION.

While employing his skills on Charlestown projects, Loammi Baldwin II lived on School Street in a lovely mansion only recently fallen to the hands of progress. To Loammi II there also fell by good or ill fortune the survey task for the proposed canal across Massachusetts. His estimate of a cost of $2,000,000 was much too low, although an honest mistake. It will go down in history as the type of ludicrous error that a brilliant, honest man could make in those days.

The other sons of the famous sire, George, Edward, etc., all distinguished themselves in various ways. They were influential railroad builders – in fact of the Boston and Lowell Railroad that put the Middlesex Canal out of business, as earlier described.

On driving south over Route 128, as one approaches North Woburn and the overpass for Route 38 (Exit 39) a highway marker announces the Middlesex Canal and sure enough, there are sizeable puddles, in the ditch north and south of the massive highway. Close by appears a gigantic shopping center. Just east of that on the right stands a house that is commanding even today. Its lines, fenestration and trim speak in no un-certain terms of former grandeur. This was the ancestral home that Loammi Baldwin enlarged and beautified, by chance so close to his beloved canal.

Facing the massive super-highway, down beside Route 38 is a small, grassed triangle with an excellent statue of this good public servant. It is flanked by two handsome arbor vitae trees planted by a hand that had no mind for their eventual size, since they now envelop and largely obscure the statue. A canon stands in front of the statue that can have no meaning except as a symbol of this figure’s friendship for the stellar Count Rumford, whose basic discovery of the mechanical equivalent of heat was prompted, as is well known, by the fact that when canon was bored by his men, he found them too hot to handle. Unfortunately, the surrounding carpet of beer cans (annually removed) can in no way be related to the commanding figure of the statue.

This little ensemble stands on what used to be a great sweep of luxuriant lawn, landscaped and flower-bedded, rolling from the mansion above to the placid stream below. Down there in silent majesty the wealth of the North, mute and mighty in barge and boom, slipped noiselessly past, half glimpsed through the canopy of hanging branches. Occasionally, as if to break the spell of silent service, a brightly painted barge with well-dressed, gay and noisy people would glide rapidly past and sometimes even tie up at this particular landing. Then the small human figures would troop gaily up toward the great mansion. There would be gracious wining and dining in the lower stories throughout the day. In the evening, the top floor ballroom would resound to the glitter and music of the liveliest and most tasteful entertainment society could provide. Most of the time the lovely green estate was rather quiet except for the sound of the myriad birds in the thick forest trees and the gardeners at their eternal clipping, while the great lawns rolled in respectful silence from the house above to the stream below.

Today that lawn is a desert of bare sand and gravel. The lower stories and the great ballroom of the house are cut up into small apartments. The stream below is now a puddle draining in the wrong direction. It is still there, however, with plans afoot for its rejuvenation.

WATERBORNE PROCEDURES, PROCESSES AND CARGOES

Great canals already existed in England and in France when the Middlesex Canal was still a dream. The experienced British engineer Rennie wrote in a letter of advice, “Very few machines for lessening labor in canals have been found to answer the purpose.” This disadvantage the engineers of the vast Erie Canal largely overcame, especially in stump-pulling, but it was the unenviable task of the Middlesex Canal to show that a canal could be built at all. Thus, it was that wheelbarrows, man-carts, single-horse carts, wagons, and boats were the only listed conveyances. Also, railways are mentioned, meaning a double line of planks as a bed for wagons. These wagons were lowered some by Sullivan so that a workman could dig under a hummock, back the cart in under it, and pry the hummock forward into it without a shovel. He could properly write, “The cart can be discharged of the loading as quickly as a wheelbarrow.” Stones and rocks could not easily be “blown” since black powder was a highly defective and actually a dangerous agency. A sizeable rock in the bed of the canal could be removed by floating a boat up to it, draining the canal, loading the rock onto the boat and then floating it off inside the boat after refilling the canal.

Continuous use of pumps had to be made, sometimes twenty-four hours a day, when laying stone foundations for the deep locks in the Merrimack River. These were simple bored logs, sometimes twenty feet in length with leather-flanged plungers. A large model might be run by a horse. The engineers contrived a “boring machine” for preparing such long holes.

A common question about the canal was about the need for lining the canal ditch. When it ran high above the level of the countryside, a special effort had to be made to keep the water from draining out of it. A “puddle gutter” could be formed for this purpose, meaning that sifted earth was used as a lining for the banks and pounded down. Layers of well-worked loam or clay would have done the trick, but this was never really done properly. The full thickness of such a set of layers might be two to three feet. The average quality of earth throughout the canal was not so porous as to require the best of puddling nearly everywhere with the result that this art was not perfected much of anywhere, along the Canal. The water leaked to some extent in many places, particularly at aqueducts, which really some time looked as though they were made of cheese.

Farmers did complain, sometimes with violence, of their damage from seepage of water into their fields, but it finally came to be the legal view that seepage was inevitably associated with canals and could not be regarded as the fault of the company. Devices accordingly had to be developed to counteract it, since continued seepage could turn into a washout, especially when aided by the lowly muskrat who found the banks of the canal, as we’ve observed, the perfect answer to his perennial housing shortage. As soon as several bad breaks had occurred, however, causing the canal to become for miles a roaring, scouring flood, the precaution was taken of installing stop gates at convenient places to prevent flooding. Overflow weirs were also developed to prevent undue height of water giving rise to high pressure at embarrassing locations.

The infant state of industry, those days, is hard to conceive today. It can be gained from the difficulty afforded all attempts to do things that seem so simple today, such as making those basic mechanisms of the gate valves or shutters that must rise to let water into a lock. In this design, cogged bars or rails about three feet long with doublet-staggered rows of teeth were necessary, as well as small cogwheels and, other parts. It was almost impossible to get these to specifications in this country. Industry could neither cast nor machine them.

Then came the question of hydraulic cement concerning which nothing was known except what the truly ancient authorities had alleged to be true. Portland cement did not come in until 1860. However, by vast experimenting, sending ships to foreign parts for special substances, Baldwin finally emerged with a cement that stood up. Thus, there was thrust upon the Middlesex Canal a continual pioneering effort in difficult and ultimately very valuable fields of technological knowledge. Many a canal company in the years ahead would bless Middlesex Canal industry, skill and perseverance.

On reflection, some have wondered, although seldom for long, what the hinterland could offer in whose behalf this seemingly stupendous canal-building effort was made. Perhaps for sheer indispensability, the great timber booms we have discussed were the richest and most unique haul. Without them it is difficult to imagine the struggling young nation as a maritime power to be taken seriously — one that would indeed fight Britannia to her knees upon the very waves she purported to rule. For truly, what Cedar of Lebanon would not have traded its tap root to have sired or even have dwelt among a grove of such sylvan dignitaries as could be seen daily floating in silent majesty down this silver stream.

Athwart every road forking out from the canal freight terminals of the Upper Merrimack, for mile upon country mile, was the true gold mine of the Canal – the thousands of humble homes self-sufficient enough to endure the rigors of New England winters and the obduracy of its soil but yearning in this life for just one touch of softness of refinement, gentleness, learning and even of occasional frivolity. Perhaps a dozen eggs a week would bring such a bonus once a year; several tons of corn might bring it in abundance. Always the cities must be fed, so, if necessary, the pet calf could go or the old bull. The latter especially might show up in the Charlestown or eventually in the North Cambridge stockyards, (below where the Porter Square Railroad Station is today), ending perhaps as a Porterhouse steak in the Porter House Hotel up above on the hill in the present Porter Square. But there was no home, however humble but what could accumulate and save its fireplace ashes for periodic collection by the itinerant drummer. This odd product, unfamiliar because mined today, was the major source of potash so necessary for lye for soaps and other byproducts. It appeared on a great many bills of lading as potash, or fire ash, the hallmark of the little fellow and his ticket to a glimpse of better things. To him, indeed, the Middlesex Canal was a river in the sky.

SOFT, SWEET LIFE ON THE CANAL

The number of taverns grew to accommodate passengers from Charlestown to Boston and from Middlesex Village to newborn Lowell. The long trip is variously described, the packets being “protected by iron rules (described earlier) from the dangers of collision; undaunted by squalls of wind, realizing, should the craft be capsized one had nothing to do but walk ashore. He had plenty of time for reflection and observation. Seated in summer under a capacious awning, he traveled the valley of the Mystic .... where soft bits of New England scenery, clear cut as cameos, lingered caressingly in his vision; green meadows, fields riotous with blossomed clover, fragrant orchards and quaint old farmhouses with a background of low hills wooded to their summits.”

Brenton Dickson relates, “On the Middlesex Canal, Horn Pond in Woburn was a favorite place to go to on a holiday, being readily accessible by boat. Pleasure barges took passengers on scenic trips around the lake while “Kendall’s Brass Band” and the “Brigade Band of Boston” rendered sweet harmony, and the crowds wandered from the groves to the lake and back to the Canal.”

Horn Pond had the great advantage that there were three double locks in its vicinity – which could keep the very young and the very old captivated all day. Also, the pond was neither too swampy nor large to walk around, nor so small that a spooning couple could get back too soon. Chiefly, however, it had an island (then and now) in the middle with a sizable eminence on it and lastly, as observed, it was a mere nine miles from the great city. A more natural all-day picnic place could scarcely be imagined, nor need be, for Bostonians flocked to it in hundreds.

The Company built a small tavern on the east side of the stream at the upper locks with a bar room for men. By 1824, a second, larger tavern was built similarly at the middle locks where sizable events, such as Masonic installations, were held. By 1827, an enlarged tavern was flourishing there. Then a still larger tavern with two wings just south of the first was built to sleep about twenty and board several more. There was a large pavilion house on the hill near the wharf for dancing parties, and another one near the hotel. In the pines near the wharf were two open air bowling alleys. On the island down near the pond was a large building with a restaurant and bowling alleys. Many boats, some with as many as a dozen people, scurried around constantly. A boat used as a ferry ran continually back and forth to the island. Here was a fun town in the early 1800’s.

The proliferation of taverns and overnight accommodations occurred at nearly every major locking; so that good fare could be counted and calculated on, timewise. In addition to the various taverns at lock locations, many existed even before the Canal’s successful operation. Thus, the names of Page, Lewis, Pollard, Marshall, Durin and Manning were well known as Blanchard’s at Medford, Dean’s at Wilmington, Richardson’s at Woburn, Allen’s near the Shawsheen, Frye’s at Lowell and ultimately the Columbia at Medford. Finally, was The Bunker Hill in Charlestown.

The American birth rate was rising. National population soared at unheard of rates during these years — this was the one country in the world where there was plenty of food grown — more than was needed. If you could pay for your liquor, you could often have your meal free. Much of the man and muscle power of those days was seemingly fueled directly on the internal combustion of alcohol.

In “Bright Promise,” by Jan Nickerson, Funk & Wagnall - 1965, the author spins an early tale of New England in the early parts of the 19th century, when bright, strong-visioned women were striving to get out of the kitchen by picking up money through mill work. She weaves the Canal in and out of the picture like the pattern of a tapestry, as her heroine makes use of it quite naturally for her transportation to Lowell, the essential funding-lodge of her dreams. It is, if brief, a handsome, satisfying picture.

In 1967, Mary Stetson Clarke published “The Limner’s Daughter”, an interesting tale of living entirely dependent in numerous places upon the tiny silver ribbon of that fistful of water, the Middlesex Canal.

More than spirited, imaginative authoresses launched their lot upon the sinews of this well-designed stream. Space limits mention them all, but the Harvard Doctoral thesis of Christopher Roberts is outstanding for reams of factual, applicable material often in captivating style “The Middlesex Canal”, Harvard University Press, 1938.

There followed another “Middlesex Canal”, by Louis M. Laurence in 1942 with an immense amount of additional information and many invaluable records, a thoroughly well documented chronicle.

The Canal became a comfortable appurtenance of the ways of living and of thinking of those times. It did not plunge its users by intricate and mysterious devices into an age far ahead of their times but moved them literally and figuratively through the forests and cities of their day with an elementary dignity, purposefulness, efficiency and success that strengthened. their peace of mind and catered to their appreciation of actual beauty. It was a nice thing to have around.

Moses Whitcher Mann, writing in 1908, fifty years after the last boat had passed through, laments the passage of the Canal. He says, “At Middlesex Village, where the entrance was into the Merrimack, is the ‘Hadley Pasture’, once a scene of activity, as the boats went up. and down the three steps of the fine locks. All these are gone, but the little office of the collectors remains on the hill beside the lock site, and cows graze quietly under the trees which have grown up in the excavation. Far different is the change near its old south terminal from the quiet canal travel to the strenuous “rush hours” of the Elevated trains near Sullivan Station”.

What indeed would Mann say to learn today of the imminent removal of that hideous structure; that the Elevated had run its full circle and was itself earmarked for immediate removal along with the Terminal Building that has stood for some 3/4 of a century as mausoleum for the buried body of the Canal. Still mightier structures now span the one-time Neck and have physically severed the corpus of the old canal to provide for depressed automobile transportation at speeds of 50 miles per hour.

Little remains for us today except to speculate on what some reader at the turn of the century may, with a wry smile, have to say should his eye alight on these mid-century pages of ours.

BETWEEN THE LADIES – A TRIP ON THE CANAL

Miss Fanny Searle wrote to Mrs. Margaret Curzon a letter describing a brilliant socialite picnic on the canal that includes references to the ever-romantic figure of Daniel Webster. The canal as a fun spot for young and old, rich and poor, was never more eloquently described. Their words were flowery, but their joys today seem so simple.

“. . .We entered the boat in Charlestown and set off at 1/2 past nine; the water gave coolness to the air and the boat (the packet “Governor Sullivan”) being covered, gave shelter from the sun, and the party was too large to have any stiffness; indeed, there was utmost ease and good humor without sadness throughout the day. The shores of the Canal for most of the distance are beautiful. We proceeded at the rate of 3 miles an hour, drawn by 2 horses, to the most romantic spot (Horn Pond) (about nine miles from Boston) that I ever beheld; you have not, I believe seen, though I dare say you have had a description of this spot. Mr. J. L. Sullivan (son of Governor Sullivan) has erected a little building on the banks of a lake most beautifully surrounded by woods and occasional openings into a fertile country. The lake is about twice the size of Jamaica Pond or larger and has a small wood-covered island in the centre. On the island a band of music was placed which began playing as soon as we landed. It seemed like a scene of enchantment. Cousin Kate (daughter of Samuel Eliot) who was by my side seemed too affected to speak. Kate happened to be at Mrs. Quincy’s on a visit of a week and went as one of her family. Oliva Buckminster was with us, her sisters declined. I was truly sorry not to have Eliza there. We had Mr. Webster (Daniel), Savage: (President, Massachusetts Historical Society), Callender (Clerk of the Supreme Judicial Court), Tudor (William, founder of the North American Review and the Boston Athenaeum), H. Gray, P. Mason (Reporter of the United States Circuit Court), Russell Sullivan (Rev. Thomas R., son of John Langdon Sullivan), and two of his college friends, - Emerson and Sam May (Rev. Samuel), with whom I was very much pleased. Besides the Mr. Sullivans (were) Mr. Quincy (later President of Harvard) and Mr. Amory, making in all a pretty large number. Having so many wits at the party, there was no lack of bon mots ….The ascent of the Canal was altogether new to me and very interesting; we passed 3 or 4 locks, and it was all the pleasanter for having so many children to whom it was like-wise a novelty, After we landed and had ranged about a little, the children danced on the green under a tent or awning and we had seats around them. I never saw more pretty or happy faces than the little group presented ….We again collected and re-entered the boat; tables were placed the whole length of it on which were arranged fruit, wine, ice and glasses, and we had very good room on each side of them. Mr. Sullivan made this arrangement thinking it would delay us too long if we had dessert in the pavilion, for Mrs. Quincy who had so great a distance to go; however, it seemed to be the general opinion that we had set out too soon, therefore we landed again at another delightful spot about two miles further down, where we stopped about an hour. It was a fine grove sloping down to another large pond (Upper Mystic Lake) beyond which was seen in the distance the little village and spire of Menotomy (Arlington) - a pretty termination of the view. This was as pleasant an hour as any in the day, and it was here that I was particularly struck with May. We were standing on the edge of the water and observed some pond lilies a little distance in the water, too far to be reached however without going into the water Some lady expressed a wish to have one.”

“Is there no gentleman spirited enough to come forward and get them?” asked Mr. Webster, “is no one gallant enough!” - strange! it is very strange!” May stood it so far and then darted forward urged on by Mr. W., who said he was glad the days of chivalry were not over, - “very glad to see you have, so much courage, Mr. May.” “It would have required more courage not to have done it after the challenge I received,” said May, “I claim no merit, Sir”. “A little farther, Sir,” said Mr. Webster, “there is another on your right; one on the other side,” &c. May went on till he was up to his middle, and I besought Mr. Webster not to urge him farther. “Oh,” said he, “it does not hurt a young man to wet his feet; I would have gone myself if it were not for the ladies.” May presently came back with his hands full of flowers, which he gave to Mr. Webster, and from him the ladies near each received one. Mr. Sullivan came up just then and asked May what had induced him to it. “Mr. Webster’s eloquence, Sir,” said he. “It has never procured me a lily before”, said the Orator. “Though it has many laurels”, replied May. Mr. W. bowed and thus ended this little affair, which I thought your interest in the Col. (Col. May, the young man’s father) might lead you to listen with pleasure …. I have not done justice to Mr. Webster’s words and his look and manner, (which) if you have not seen, no words of mine can point to you. It always delights me to see him, and I was never so charmed as this day. To all (the) wit and power of mind of all the other gentlemen he super-adds a tenderness and unaffected feeling that is seldom seen in his sex and especially at his time of life or in his pursuits…. Well, we entered the boat again and gently pursued our course a few miles farther when we again stopped near a house (tavern, Boston Avenue and Mystic Valley Parkway) where coffee had been prepared for us; we did not, however, enter the house, but the coffee and necessary apparatus were deposited in the boat. The children then had another cotillion while the boat was descending one of the locks, which was not so pleasant as the ascent. We then walked a short distance on the shore, got into the boat again, took coffee, listened again to sweet trains, and saw the sun descend and the moon rise in a sky beautifully bedecked by light clouds, and reached our place of debarkation just after the last tints of daylight had faded.”

LATER DAYS OF THE CANAL - THE PROPOSED PEABODY WATER SYSTEM

A work as magnificently natural as we have observed the Canal to be could well be destined to lasting usefulness years after the outmoding of its original physical frame. Long did the piercing eyes of entrepreneurs, engineers and just plain imaginers dwell on its course through farm and fen, and fertile minds speculate on potentialities. Caleb Eddy, a later capable manager, had already tried out the scheme of a Boston water supply, but changing times were to supply a theater of vaster dimensions and more startling opportunities than fate would ever permit him to imagine.

Since those days of the good Caleb Eddy, the town of Peabody has acquired a stout industrial base. Originally a substantial tanning center, the departure of this industry had been accompanied with typical Yankee ingenuity by the influx of others of a more diversified nature, such as plastics of various forms requiring considerable amounts of water in their processes. The Ipswich River, a salt-water stream running upwards from Cape Ann southwesterly to West Peabody and then creeping up westerly as far as Wilmington, is fed there by Lubber Brook and Maple Meadow Brook. In this latter stretch above West Peabody it has a sizeable basin bounded on the north by that of the Shawsheen River and on the south by that of the Saugus River. We have already heard of the marsh-like character of the Lubber and Maple Meadow Brooks and their apparently infinite capacity to absorb earth poured in to form the bed of the Canal (some sixty vertical feet of earth fill having been poured into it before stability was achieved).

In recent years it has dawned upon still vibrant Yankee minds that this infinitely sponge-like property could be used in some general sort of way (although it has never before actually been tried in this part of the country.) It was that water put into the basin cannot escape except through evaporation. Hence a modern plan has emerged to take the flood waters of the Concord River in the spring and transport them along the route of the old canal to the basin, partly in the open over the old bed and partly in conduits following that same course. The spongy basin of the two brooks would thus be filled to capacity, from which water for the Ipswich River could be milked through the summer months much more constantly than was heretofore possible except in a year of a very wet spring. By some this plan has been taken quite seriously and is presently under study by Whitman and Howard, engineers for the state. It is now in the hands of the Commonwealth Water Commission.

The notion that the canal route, once so fully operative, could presently be used again has continued to haunt numerous other business firms and glint-eyed entrepreneurs from the cities on the Merrimack. A mere fifty years ago, James O’Sullivan of Lowell urged the digging of a “Lowell Canal” under the news caption LOCAL MEN WANT CANAL TO BOSTON.

“The feasibility of a waterway suitable for transportation between this city and tidewater in Boston is a subject that has been treated with some consideration by several prominent businessmen here of late. What was once successful is feasible again, is their contention and with this in mind, agitation has sprung up that promises, according to those actively interested, to bring results later. A member of the local board of trade and a man prominent in the business life of the city expressed the belief of recent date that to his mind, a waterway from here to the Hub was practicable and would come sooner or later.”

SPAWN OF THE MIDDLESEX. CONTRIBUTORS AND BENEFICIARIES. The American Revolution lifted the ceiling on ambition and inspiration. There followed the Santee Canal in South Carolina by Christian Snef and the Potomac Canals across the obstreperous rapids and falls of that otherwise majestic, penetrating artery of transportation. For their utilization, manpower poling alone was available. The picture of a horse’s powerful shoulder muscles at work, so vividly etched in the minds of every practical man of those days, danced by the hour tantalizingly through their heads. Thus, New England’s restless, driving spirits wandered its hills and dales seeking the answer of transportation for their latent wealth until there came a feel for the lay of the land across the upper waters of the Mystic, Saugus, Ipswich, Shawsheen and Concord Rivers for providing practical traction for the barges that they pictured floating along.

The Middlesex Canal was the first canal to use power traction in the country. It proved instantly that the vehicle best adapted to the needs and potentialities of the growing country was indeed the traction canal. On this, basis, the mighty Erie quickly followed, ten times as long, half again as deep, twice as wide, with double and triple the barge capacity. No less than 3000 barges at 100 tons apiece were commonly in dogged, purposeful motion upon it. Within a half century more than 25,000 miles of canal were built to accommodate the commerce of this burgeoning country while untold thousands more were not attempted, mercifully confined to the brains of the overly ambitious.

It is interesting to note that the early American canals were trenches for barges, dug along the side of the river and nourished from it. The trench notion then developed into the more decisive purpose of cutting canals for ships through isthmus formation like Panama, Suez and Soo Saint Marie (which surpasses the total tonnage of the other two).

The thoroughly modern notion finally evolved of damning a river with some frequency, thereby making the entire stream its own smooth-surfaced ship canal with locks at the dams. Witness today’s splendid Illinois River Canal, not to mention 52-foot lifts and 12-foot square raceways in lock after lock of the stupendous Tennessee and Cumberland. Today a single small tug can push ten one-thousand ton barges up such a stream at one time. But the dreamers are not finished, mention was early made of canals to bring Arctic melt water to parched countries and a liquid ribbon from the Great Lakes to the Pacific. If today is an age when dreams come true, so also was the opening of the 19th century. Our tale has been one of these unique and triumphant realizations.

Many events of those early Boston years were closely associated with the development of the Canal. The most important adjunct, though antedating the Canal by some 17 years, was the building of the Charlestown Bridge. Suitable savants had pronounced a permanent structure from Boston to Charlestown impossible, but private enterprise put a toll bridge across the tide-ripped channel, even including a draw. The opening was scheduled for and held on June 17, 1786, only three years after the end of the war and was attended by a vast “multitude”.

All heads turned now to the north of Boston as a more direct and simpler source of living and trade. It transformed the entire north end of the peninsula from a backwater, residential suburb to a “roaring traffic mart.” It unquestionably accelerated thinking about the Canal as a potential contributor to and beneficiary of bridge traffic.

The freight volume of the Canal could never have been handled by the Boston terminus alone. It required and employed distribution points, particularly as it neared the more densely settled areas near Boston. Thus, the great lumber booms were shunted off at Medford. Much food and produce were transshipped from Charlestown, in fact all of it in later years after the filling of the east cove in Boston and the abandonment of that terminus. Much needed produce and wares which were unloaded in Charlestown came to Boston over the Great Bridge. All passenger traffic came this way and boarded the packet; or debarked at one of two major stopping places, such as the Bunker Hill Tavern at the corner of Mill and Main Streets in Charlestown right at the dam of the Mill Pond, or just beyond the neck in what is now Somerville.

In 1813, a lean year by any standards, we find in the Sentinel, “The large Hotel and Tavern in Charlestown (now Somerville) for several years occupied by Colonel Page and known by the name of Page’s Tavern, will be vacant and to be let in a few months. This establishment is advantageously situated at the meeting of several great roads and near the outlet of the Middlesex Canal, one mile and a half from Charlestown Bridge. It is at a convenient distance from Boston for the accommodation of travelers who desire an airy and tranquil lodging in the vicinity of the Metropolis, and especially for those who wish to leave their horses at pasture while transacting business in town. The yards for droves of cattle which are eventually destined for the Boston market have lately been increased by the addition of three enclosures, each seventy-five feet square, the fences of which are of suitable height and strength. There are also pens for droves of sheep and hogs. The House and Outbuildings are spacious, - the garden is large and there are seventeen acres of pasture attached to the homestead. The whole establishment is on a large scale, and well calculated for a Pleasure House, Tavern and Cattle Fair. Apply to Richard J. Sullivan, (progenitor of Sullivan Square).

An especially important adjunct of sizeable cities was early the cattle-pen area or stockyard facility. We’ve watched this move steadily West in our own day until now it is certainly as far west as Omaha, with little left at Chicago of those once-famous yards. With the advent of the Charlestown Bridge, sizeable portions of this industry, as seen from the ad above, apparently began to form and moved out to the very edge of the mainland where the first available abundance of space lay. Later when the Cambridge bridges were also established, quite sizeable pens were in North Cambridge at Porter Square, encouraging the Porter Hotel where loud, red-faced drovers and other hearty eaters could choose the best cuts from their own stock. This hotel gave rise to the famous Porter House steak whose euphonious syllables still suffice to make gourmet mouths water.

Such establishments were numerous along the canal and in turn fed on the Canal, helping it prosper and grow. They used very directly its cordwood, lumber, produce, building material, passenger transportation and turned elsewhere only with great inconvenience. True it is that the Canal never paid back wealth-bringing dividends to its investors but in such ways, it strengthened and developed the entire countryside through which it ran. In such respects it was a roaring success, a real “river in the sky,” fitting progenitor of the Great Erie.

MISCELLANY

Back Issues – More than 60 years of back issues of Towpath Topics, together with an index to the content of all issues, are also available from our website http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath. These are an excellent resource for anyone who wishes to learn more about the canal and should be particularly useful for historic researchers.

Estate Planning – To those of you who are making your final arrangements, please remember the Middlesex Canal Association. Your help is vital to our future. Thank you for considering us.

Membership and Dues – There are two categories of membership: Proprietor (voting) and Member (non-voting). Annual dues for “Proprietor” are $25 and for “Member” just $15. Additional contributions are always welcome and gratefully accepted. If interested in becoming a “Proprietor” or a “Member” of the MCA, please mail membership checks to Neil Devins, 28 Burlington Avenue, Wilmington, MA 01887.

Middlesex Canal Association Officers and Directors: http://www.middlesexcanal.org/directors.htm

Museum & Reardon Room Rental – The facility is available at very reasonable rates for private affairs, and for non-profit organizations to hold meetings. The conference room holds up to 60 people and includes access to a kitchen and restrooms. For details and additional information please contact the museum at 978-670-2740.

Museum Shop – Looking for that perfect gift for a Middlesex Canal aficionado? Don’t forget to check out the inventory of canal related books, maps, and other items of general interest available at the museum shop. The store is open weekends from noon to 4:00pm except during holidays.

Web Site – The URL for the Middlesex Canal Association’s web site is www.middlesexcanal.org. Our webmaster, Robert Winters, keeps the site up to date. Events, articles and other information will sometimes appear there before it can get to you through Towpath Topics. Please check the site from time to time for new entries.

The first issue of the Middlesex Canal Association newsletter was published in October, 1963.

Originally named “Canal News”, the first issue featured a contest to name the newsletter. A year later, the newsletter was renamed “Towpath Topics.”

Towpath Topics is edited and published by Debra Fox, Alec Ingraham, and Robert Winters.

Corrections, contributions and ideas for future issues are always welcome.

Bill Kuttner, Andrew Jennings, Doug Chandler, Marlies Henderson, J. Breen (Jan 26, 2025) Missing - Phil Belanger.

The Friends of Regional Trails and Towpaths, or FORTT, explorers of the Thoreau Towpath between the Freeman Rail Trail tunnel under Rte. 3

at Cross Point Towers, Lowell, and the Bellegarde Boathouse, Lowell, on the left bank of the Merrimack River near where Thoreau and his brother John

had lunch in 1839 at the end of their voyage on the Middlesex Canal as related in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

FORTT has the goal of making the towpath part of a regional trail.