Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 51 No. 2 | January 2013 |

MCA ACTIVITIES

Mark your calendars!

Our Winter Meeting will be held at the museum on Sunday, February 10th, 2013, beginning at 1 PM. Dave Barber, President of the American Canal Society, will present "Unusual and Remote Canals." Refreshments will be served.

In 2013, the Association will sponsor two bike tours of the canal, south from Lowell on Sunday, April 7th, and north from Charlestown, likely on Saturday, October 5th.

The Spring Meeting will be held on Sunday, April 28th, 2013, in the museum, beginning at 1 PM. There will be an election of officers, also, bylaw change proposals will be presented and voted on. Following the business meeting, our speaker will be Dr. Patrick Malone, author of "Waterpower in Lowell". Refreshments will be served.

The MCA-AMC Spring Walk will take place in Wilmington on Sunday, May 5th.

See the Calendar, following, for more information on our activities. Also included in the calendar are meetings and tours, sponsored by other canal related organizations, in which you may want to participate. Please also check our web site now-and-then, at the URL noted in the nameplate, above, which also lists canal-related events and topics of potential interest, sometimes including those that don't make it into Towpath Topics.

PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE

by J. Jeremiah Breen, jj@middlesexcanal.org

The Boston Marathon is 26.2 miles. From the Merrimack River to the Charles, the Middlesex Canal is 27 miles, 18 chains, and 66 links (27.2 mi) as surveyed in 1829. Eureka, the Middlesex Canal should be a marathon, a new benefit for our generation, following on Baldwin's prayer at the 1794 groundbreaking, "May the Eye of Wisdom and the Eternal Mind aid this work designed for the benefit of the present & all Future Generations."

With Boston already famous for a foot race, and not enough watered canal remaining for an ice skate or boat race, a Middlesex Canal race at marathon distance would be for bicycles. Racing from Lowell's Hadley Field to Charlestown's Bunker Hill Community College would take, say, an hour, based on a Tour de France time trial record over 34 miles at 34 mph. The course could be as simple as Stedman St, route 129, route 38. The problem with the course is the hazardousness of routes 129 and 38, two lanes without shoulders and 40 mph traffic for miles. A mountain bike race using the towpath was a possibility to reduce the road miles, but mountain bikers are not interested in flat racing. To reduce the hazard from speeding cars, rather than starting at 10 am like the Boston Marathon, the Middlesex Marathon Bike Race would start at 7 am on a Sunday.

A seven o'clock start at Hadley Field would also make a return from Boston on the Lowell Line's 10 am train convenient for cyclists who are not Tour de France professionals.

The financial sponsor for the race could be John Hancock Financial Services, the same company sponsoring the Boston Marathon, for which more than a million dollars in prizes and bonuses are to be awarded in 2013. A Middlesex Marathon would have an historical basis for Hancock sponsorship. Governor John Hancock signed the act incorporating the Middlesex Canal Company. He was the first proprietor of the corporation, a signal recognition given when share certificates were printed in the year after his death and he was posthumously issued share certificate No. 1. The Middlesex Marathon should have sponsorship from John Hancock Financial Services in less than the 89 years the Boston Marathon was run before sponsorship given Gov. John Hancock's sponsorship in 1793.

In 2013, the Association will sponsor two bike tours of the canal, south from Lowell on Sunday, April 7th, and north from Charlestown tentatively on Saturday, October 5th. In 2012, the Spring tour had 33 cyclists and Fall had 17. One cyclist joined the spring tour at Billerica after racing in the morning. Notice of the tours is published in the Yahoo! group email of the Charles River Wheelmen which has over 1500 members, but many do not subscribe to the Yahoo! group. The monthly newsletter is a better way to reach more of the Wheelmen even though it is only available as a PDF download. A volunteer is needed to write an article for the newsletter describing the two tours and a future Middlesex marathon.

Note on Canal Length.

While the 1829 survey of 27.23 miles is the length of the canal, the Boston and Maine culvert at the northern end of the canal is identified by mileage post 27.39. At the southern end of the canal, the distance between canal 0+00, Rutherford Av at A St, and railroad 0.00, the North Station buffer stop, is one mile, thus the railroad measurement comparable to the the canal is 26.39. The 1836 plan of the railroad, (http://tinyurl.com/au7xqme), which shows the canal also, shows the 0.9 mile greater length of the canal compared to the railroad is due to the canal having more curves. The railroad plan included a detailed map of the canal because the engineer of the railroad, James Baldwin, was canal superintendent, 1821-24, and his 16-years-younger brother George also worked for the railroad and did an 1829 survey of the canal.

J. Jeremiah Breen

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MCA Activities

President's Message (J.J. Breen)

Calendar of Events

For Future Planning

Fifty Years of ... Towpath Topics

More on the Baldwin Dry Docks

Historical Middlesex Canal Document

Bylaws - An Early Alert

Fiftieth Anniversary Tour (Silva, Breen, & others)

The Baldwin Shovel (Gerber)

What Could It Have Been Used For? (Gerber)

Toll House Facelift (Gerber)

The Middlesex Canal (Lorin L. Dame)

Miscellany

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

Middlesex Canal Association (MCA) and related organizations

First Wednesday - MCA Board of Directors' Meetings - The Board meets at the Museum, from 3:30 to 5:30pm, the first Wednesday of every month, except July and August. Members are always welcome to attend.

Directions to the Museum/Visitors Center: Telephone: 978-670-2740.

By Car:

From Rte. 128/95, take Route 3 toward Nashua, to Exit 28 "Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle". At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at a fork. After another ¾ mile, at a traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A. Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road, Talbot Street, which will put St. Andrew's Church on your left. Go about ¼ mile and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the falls, where Old Elm becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the falls.

From I-495, take exit 37, N. Billerica, south to the road's end at a "T" intersection, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700' and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street.

By Train: The Lowell Commuter Line runs between Boston's North Station and Lowell's Gallagher Terminal. Get off at the North Billerica station, which is one stop south of Lowell. From the station side of the tracks, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station and Faulkner Streets on the right side.

Jan 15 to Apr 20, 2013 - The West End Museum 150 Staniford Street, Boston, MA 02114, will present a free exhibit Connections North: Bridges of the West End. Spanning 300 years, the exhibit tells a story about the bridges that changed the entire face of Boston: the Charles River Bridge, West Boston Bridge, Canal Bridge and Warren Bridge, along with their design and construction, and the political intrigues they stirred up! The museum is open Tues. to Fri. from 12 to 5pm, and Sat 11am to 4pm. There will be a reception on Tues, Jan. 22, from 6:30pm - 8:00pm. See http://www.thewestendmuseum.org/whatson.html for more information.

Sun, Feb 10th, 2013 - The MCA Winter Meeting will be held at the museum beginning at 1 PM. Our speaker will be Dave Barber, long time proprietor and past board member of MCA, president of American Canal Society and the Blackstone Canal Conservancy, and author of guides to the Lehigh Canal and the Delaware & Hudson Canal. Dave will present "Unusual and Remote Canals" a sampling of canal sites, most still in use, scattered throughout the Northeast and Midwest. Refreshments will be served.

Thurs, Feb 21, 2013 - BoD member Bill Gerber will give a presentation on the Canals of the Merrimack at the Chelmsford Library on at 7 PM. See http://www.chelmsfordlibrary.org/programs/programs/bill_gerber.html for details.

March 2, 2013 - Canal Society of NY State Symposium and Winter Meeting at Monroe Community College, Rochester. Follow this link for "Call for Papers," www.newyorkcanals.org/explore_symposium.htm

Thurs, Mar 21, 2013 - Annual Meeting of the Middlesex Canal Commission at 3:15 PM, at the Museum. MCC meetings are open to the public.

Sat, Mar 30, 2013 - Lock Tender Training, conducted by Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust, supporting Concord River Whitewater Rafting. To be held at 10 AM at the UMass Lowell Inn & Conference Center, 50 Warren Street, Lowell MA. Learn to operate a "real" lock! Training is conducted at Warren Locks on the Pawtucket Canal (aka Lower Locks and Concord Locks). Volunteer lock tending shifts are Saturdays and Sundays thru April and May and last from 10:30 AM to 12:00 PM and 2:30 PM to 4:00 PM. Proper training and a signed release form are required for all lock tenders. For further information - Gwen Kozlowski, Stewardship & Education Manager (gwen@lowelllandtrust.org), Mon. to Thurs., 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM.

Sun, April 7, 2013 - Spring Middlesex Canal Bicycle Ride. Meet 9:30 AM at North Station (commuter rail) and take our bicycles on the 10 AM train to Lowell. (Riders can also board at West Medford at 10:11 or meet the Train when it arrives in Lowell at 10:43). Route visits the Pawtucket and other Lowell canals, the river walk, Francis Gate, and then Middlesex Canal remnants in Chelmsford. Lunch at Route 3A mini-mall in Billerica. Quick visit to Canal Museum, then on to Boston. Long day, but sunset is late. Riders needing to leave early can get the train to Boston at 1:07 at North Billerica or at 3:14 at Wilmington. Participants are responsible for one-way train fare [$6.75 from Boston to Lowell]. Complete Lowell line schedules can be downloaded at http://www.mbcr.net for anyone who wishes to plan a rail travel itinerary specific to their needs. For any changes or updates, see http://middlesexcanal.org. Leaders Bill Kuttner (617-241-9383) & Dick Bauer (857-540-6293).

April 5-7, 2013 - The Canal Society of Indiana's spring tour of the Wabash & Erie Canal, Attica to Montezuma, Indiana. HQ: Sleep Inn, Danville, Illinois. See canal remains, murals, a covered bridge, a war memorial museum, a waterfall, and much more on this three-day adventure. More information to follow. 260-432-0279.

April 26-28, 2013 - Canal Society of NY State's spring tour of the Delaware and Hudson Canal Northern End, Kingston to Port Hyxson. In addition to exciting 19th century canal sites, including a Roebling canal aqueduct remnant, we will see the Hudson River port at Roundout where it meets the river and the historic Rosendale cement industry, a canal museum, and a maritime museum. A boat trip to a Hudson lighthouse and up the Round-out is possible as well. See http://www.newyorkcanals.org.

Sun, April 28, 2012 - MCA's Annual Spring Meeting will take place in the museum, at 1:00 PM. Proposed changes to our Bylaws will be presented and voted on and election of officers for the forthcoming year will occur at that time. Following a short business meeting, our speaker will be industrial archaeologist and historian of technology Dr. Patrick Malone, Professor Emeritus of American Civilization and Urban Studies and former Director of the Urban Studies Program at Brown University. His topic, Waterpower In Lowell is the subject of a book he recently published. Refreshments will be served.

Sun, May 5, 2013 – Joint MCA-AMC Spring Middlesex Canal Walk. Meet at 1:30pm; Wilmington, MA. Walk a rural section of the canal from near the Wilmington Town Park to Patch's Pond, once a canal basin. Examine grooves worn in a boulder by towropes as boats wound around the Ox Bow; also the remains of Maple Meadow Brook Aqueduct, and a quarry used in its construction. Directions: From Route 128/95 take exit 35 in Woburn. Follow Route 38 (Main St.) north 2.4 miles to the Wilmington Town Park on the left just prior to the railroad overpass. For more information see our web site - http://middlesexcanal.org or contact: Roger Hagopian (781-861-7868) or Robert Winters (617-661-9230, robert@middlesexcanal.org).

Sept 16 to 19, 2013 - World Canals Conference in Toulouse, France, along the Canal du Midi, with accompanying excursions prior to and following. See http://www.wcc13.com/en/ for details.

Sept. 20-22, 2013 - The Canal Societies of Indiana and Ohio will sponsor a trip to Delphi, Indiana. 2014 - World Canals Conference, Navigli Lombardi, Milan, Italy

FOR FUTURE PLANNING

Tentative Dates for Fall MCA activities are as follows:

October 5, 2013 - 11th Annual Bike Tour North, starting at 9:00am

October 20, 2013 - MCA-AMC Fall Walk in Woburn

October 27, 2013 - Fall Meeting, 1:00pm at the Museum . These dates may change slightly based upon the personal schedules of trip leaders and speakers.

A REMINDER

Fifty years of back issues of Towpath Topics, together with an index to the content of all issues, are available to you on-line at http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath/. These are an excellent resource for anyone who wishes to learn more about the canal and should be a goldmine for historic research.

MORE ON THE BALDWIN DRY DOCKS

For those of you who may have a continuing interest, there is an excellent short history of the Baldwin Dry Docks, written by Stephen P. Carlson, Preservation Specialist at the Boston National Historical Park, at http://www.hnsa.org/conf2004/papers/carlson.htm. The paper is an expanded excerpt from a draft historic resource study of the Charlestown Navy Yard.

IMPORTANT HISTORICAL MIDDLESEX CANAL DOCUMENT

Caleb Eddy's 1843 Historical Sketch of the Middlesex Canal is now available through http://books.google.com.

BYLAWS - AN EARLY ALERT

At the Annual Meeting of the MCA, in the spring, recommended changes to the Association's Bylaws will be presented. A copy of the current Bylaws can be found at http://middlesexcanal.org/bylaws.htm.

50TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR OF THE CANAL

by Russ Silva, J. J. Breen & others

On Sunday, November 4th, the Association sponsored a bus tour of the Middlesex Canal to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the MCA's founding. The weather was a bit windy and cool, but sunny and clear, pretty good for mid-autumn.

The tour followed the entire length of the canal, proceeding north from the museum in Billerica to "Middlesex Village" in Lowell, then to the southern section of the canal's route from Charlestown and Boston to Woburn and return.

Among the participants in the photo above are: J. Jeremiah Breen, current MCA President; Fred Lawson, a founder and honorary

director of the Association; Tom Raphael, a director of the Association and chairman of the Middlesex Canal Commission; Neil

Devins, membership secretary; Russ Silva, corresponding secretary; Bill Gerber, editor of Towpath Topics, a director and former president.

Stops on the northern segment included: the site at the edge of the Billerica Mill Pond where the construction began and where the floating towpath crossed the pond; the glass workers' house, ca 1802, at Middlesex Village; and on the bank of the Merrimack opposite the location of the canal's northern end. Here, Bill Gerber spoke to the group about the northern end of the canal and the river navigation that extended north to Concord, NH.

The bus then took us down routes 3 and I-93 to Charlestown and Boston. Passing through Sullivan Square, we stopped at Bunker Hill Community College near A St, the southern end of the canal, aside a tumulus, so-called, the former site of the Charles River tide lock.

The bus then took us down routes 3 and I-93 to Charlestown and Boston. Passing through Sullivan Square, we stopped at Bunker Hill Community College near A St, the southern end of the canal, aside a tumulus, so-called, the former site of the Charles River tide lock.

Continuing briefly into Boston, we viewed the sidewalk marked to show the location of the Mill Creek Canal. Turning north again, we followed the canal route through Medford's Brooks Estate and along the Middlesex Fells Parkway past the area of the Mystic Lakes Aqueduct in Winchester. In Woburn, there was a brief stop at Horn Pond where Tom Raphael remarked upon life at the canal's secondary water source. Two hundred years ago, Horn Pond was also a tourist destination, as city dwellers rode the canal there "to take the county air" free from the city's summer crop of horse flies.

Passing the former location of the Horn Pond Locks to the still watered and soon to be improved section in Woburn we arrived for lunch at Col. Baldwin's mansion, now the Sichuan Garden II restaurant. Joining us here, was Len Harmon,an honorary director of the Association and first chairman of the Middlesex Canal Commission (established by the Commonwealth in 1977); Jean Potter, recording secretary; and Howard Winkler, MCA treasurer for the past 24 years.

Having other afternoon commitments. a few of the group left us here and returned directly to the museum. The plan was to have an half hour of talk after arrival at the mansion, giving time also for the chef to finish the cooking. Len Harmon, who in 1971 spearheaded the effort to save the mansion from demolition by moving it across Route 38 to aside the canal, was well prepared with photos of the move, and drawings of the changing shape of the mansion over the centuries.

Following the banquet, we returned to the bus and continued north along the canal's route through Wilmington and Billerica where we passed the remains of the Shawsheen Aqueduct, and then the Allen Tavern at King's Corner. Our last stop was in front of the Rogers House by the canal at the south end of the mill pond.

The land before the Rogers House, built in 1807 and the last stop on the tour, was a gift of the owners of the Faulkner Mill in 1962. The tow path and the land for a half-mile upstream was a gift, in 2011, of Leggett & Platt, Inc., former owner of the Talbot Mill. A portion of this is shown in the painting below, The Floating Tow Path, 1810, by Thomas Dahill, and a gift by him to the Association.

We returned to the museum for cake and ice cream just before sunset. We were joined at the Canal Visitor Center and Museum by Traci Jansen, vice president; Tom Dahill, a director; and Alan Seaburg, author with Carl Seaburg and Tom Dahill of The Incredible Ditch: A Bicentennial History of the Middlesex Canal. The extraordinary cake was from La Cascia's Bakery, Burlington, and was the gift of Betty Bigwood, a director of the Association and treasurer of the Commission.

The Association's thanks go to Trombly Motor Coach's driver, Jackie, who put in a long day and repeatedly demonstrated that she can turn a school bus around in astonishingly tight spaces.

Thanks also go to MCA president J. Breen who's considerable efforts to plan, organize, and direct the tour, the lunch, and the museum activities to their successful conclusions were recognized by unanimous vote of the directors at their meeting the following Wednesday.

And thanks to the thirty members and friends who joined us for part or all of the tour.

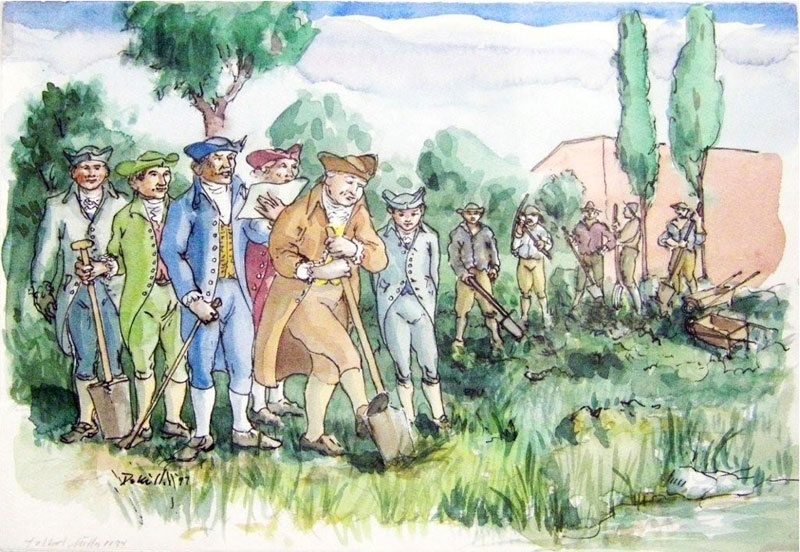

THE BALDWIN SHOVEL -- IT'S BACK!

By Bill Gerber

The shovel, which, on September 10th, 1794, Loammi Baldwin used to turn the first shovelful of earth, initiating construction of the Middlesex Canal, is back on display in our museum. When first used, Baldwin was quoted as praying, "May the Eye of Wisdom and the Eternal Mind aid this work designed for the benefit of this and all Future Generations." He was followed by James Winthrop and Samuel Jaques, each offering a short prayer as they each turned a shovel of earth. Tom Dahill captured the event in the scene he painted for the book "The Incredible Ditch", seen below.

Many years ago, perhaps soon after it was founded, two shovels that had been used during the construction of the canal were donated to the MCA by different parties. I don't know the origin of the shovel we've had on display in our own museum, Fred Lawson thinks it may have been one that had been displayed in a case in the Woburn post office. (If anyone knows about this, please tell me so that we can reconstruct the provenance of it, too.)

Many years ago, perhaps soon after it was founded, two shovels that had been used during the construction of the canal were donated to the MCA by different parties. I don't know the origin of the shovel we've had on display in our own museum, Fred Lawson thinks it may have been one that had been displayed in a case in the Woburn post office. (If anyone knows about this, please tell me so that we can reconstruct the provenance of it, too.)

But, the other shovel, Loammi's own, was donated to the Association by Baldwin descendants. One of the early 20th century canal historians, Leon Cutler, photographed this shovel propped against the front door of the Baldwin mansion; see the photo right.

Likely, both of these shovels were exhibited in an earlier MC museum; but after that closed they spent several years in the home of Bert and Fran VerPlanck, two avid MCA officers and BoD members. After Bert and Fran passed away, another responsible member took charge of them; but somewhere along the way, knowledge of the provenance of the two shovels was lost.

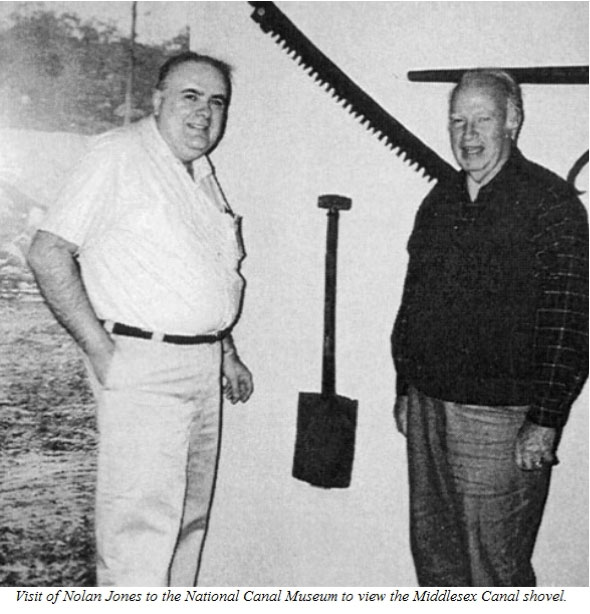

In May, 1997, the speaker for our annual meeting was Lance Metz, historian for the National Canal Museum (NCM) in Easton, PA, who gave a "pictorial tour" of the NCM and some of its new exhibits. Near the end of the meeting, then MCA President, Nolan Jones, gave Lance one of our two shovels, on an indefinite loan basis, to be exhibited among the NCM's displays. And that's where it's been for the last 15 years. This meeting, the presentation of the shovel and a photograph of the event, were published in the September 1997 issue of Towpath Topics, available at http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath/.

Sometime later, Nolan gave a talk at the NCM and Lance showed him where the shovel was displayed. This event was captured in the photo below. As of this summer (2012), the shovel was still on display, though it had long since been moved to a large display case, along with several other vintage canal construction objects.

Most recently, Howard Winkler wrote an article about the dry docks that Loammi Baldwin (Jr.) built for the Navy Yards in Boston and Norfolk; this appeared in the January, 2012, issue of Towpath Topics. This, in turn, elicited another offer from Baldwin descendants – would we care to display the models that were built as part of the dry dock design process and the selling of it to the US Navy? (We would, and the models are currently on display in our museum.) But with the models also came a question - what had we done with the shovel that the family had donated many years before. Examination of the shovel on display in our museum at that time revealed that it was not the same one that the Baldwins had donated – and it was then we realized, the Baldwin shovel was the one we loaned to the NCM; oh my!

Most recently, Howard Winkler wrote an article about the dry docks that Loammi Baldwin (Jr.) built for the Navy Yards in Boston and Norfolk; this appeared in the January, 2012, issue of Towpath Topics. This, in turn, elicited another offer from Baldwin descendants – would we care to display the models that were built as part of the dry dock design process and the selling of it to the US Navy? (We would, and the models are currently on display in our museum.) But with the models also came a question - what had we done with the shovel that the family had donated many years before. Examination of the shovel on display in our museum at that time revealed that it was not the same one that the Baldwins had donated – and it was then we realized, the Baldwin shovel was the one we loaned to the NCM; oh my!

Lance Metz has since separated from the NCM but still maintains an active interest in it. Tom Stoneback is now the Director there. When the situation was explained to them, both were gracious and cooperative with our proposal to swap shovels. The deed was done during Thanksgiving week, this year (2012), and the Baldwin shovel is now back in our own museum. Also, the provenance for it has now been reconstructed and recorded.

Since we are on the subject of the shovel, this seems like a good teaching opportunity. Our own Tom Raphael "reverse engineered" the construction of an 18th century shovel, to determine the process by which it was made. It would, of course, have been hand-made by blacksmiths of that time. Tom notes: Back in 2004, when the VerPlank's were moving out of Winchester, they had a shovel [the Baldwin shovel, as we now know]. I drew the details of its construction as Figure 5 in the diagram opposite. I then "disassembled" it, on paper, to see how it was made.

Going backwards to Fig 4 it shows it was made from a single sheet of formed iron, folded in half , and with a semicircular hollow on each side to surround the base of the handle, which had two "rivets" holding it.

Since, in those days, iron only came in blocks or rods, like Fig 1, I assumed a blacksmith heated and hammered out the sheet, as in Fig 2, shaped it as in Fig 3 folded it as in Fig 4, and finished it as in Fig 5. The face of the blade was hammered to a sharp point for digging.

I showed this before, and I feel sure it is one of the shovels we have. I don't know where the VerPlank's got it. (We now know where that shovel came from.)

A few other observations about the two shovels, since they suggest something of an evolution in technology; call them the Baldwin shovel and the Work shovel. At the time of the exchange, the two shovels were sideby-side on a table in the NCM archives at the Emrich Center in Easton, PA.

It appears to me that the Baldwin shovel was a "oneoff", whereas the Work shovel appeared to be much more of a production item, likely at least partially mass produced.

It appears to me that the Baldwin shovel was a "oneoff", whereas the Work shovel appeared to be much more of a production item, likely at least partially mass produced.

Tom Raphael's observation about the construction of the shovel blade holds for the Work shovel as well, but the latter blade (to the right in the adjacent photo) is somewhat shorter, thinner, and considerably lighter than that of the Baldwin shovel, it is also more "cupped", i.e., the side edges are turned up to a considerably greater extent.

The letters "MC" are stamped into the blade of the Baldwin, whereas "Mid Canal" is cut into the back of the handle of the Work shovel.

The handle of the Baldwin exhibits a slight natural bend near the top; it was likely carved from a tree branch, perhaps shaped using a draw-knife or spokeshave or similar tool, whereas the handle of the Work shovel is uniformly round and thus was likely turned on a lathe.

The handle of the Work shovel is slightly longer than that of the Baldwin; though both handles would be considered much too short by modern standards. (One needs to lean over too far to comfortably use either of them.)

At the end of the handle, the Baldwin has a "T" attached by a dowel through a mortise and tenon joint, whereas the Work shovel has no "T"; it's not clear if it's been lost or if it never had one.

WHAT COULD IT HAVE BEEN USED FOR?

WHAT COULD IT HAVE BEEN USED FOR?

by Bill Gerber

Long ago, when I began researching the canals, Fred Lawson served as my mentor for all things related to the Middlesex, and Chuck Mower served similarly for my research into the canals of the Merrimack. Surprisingly the two of them had never met; but, late this summer, I had an opportunity to introduce them to each other.

Very soon after the introductions, Chuck invited us to his shop in his barn (where he hand-builds Windsor chairs) with a 'let me show you something'. From the barn loft he retrieved a "pole", about seven feet long, and posed the question 'what could this have been used for'? He explained why he thought the pole was once used in some capacity associated with the canal, but what purpose did it serve?

Shown at the left, propped against the door frame of the Toll House on Chelmsford Common, the pole is probably fir, slightly taller than the door, i.e., 82-1/2" (~6-7/8') long. What one might assume is its base is 2-1/2" square for a length of 11-1/2", above which all of the remaining length is turned round to a diameter of 2-1/2".

Shown at the left, propped against the door frame of the Toll House on Chelmsford Common, the pole is probably fir, slightly taller than the door, i.e., 82-1/2" (~6-7/8') long. What one might assume is its base is 2-1/2" square for a length of 11-1/2", above which all of the remaining length is turned round to a diameter of 2-1/2".

As can be seen at right, about half the volume of the base appears to be dry-rotted for about 3/4 of its length. At a distance of 13" to 18" above the bottom of the base there is very slight evidence of wood compression on one side, which does not extend very far around. Within the distance of 53-1/2" to 66", from the bottom of the base, there is clear evidence that something was tied very tightly to the pole, perhaps various things at various times, resulting in significant and varying circumferential wear and compression of the wood at multiple places between those dimensions. The remains of a small nail, now flush with the the outer surface, was driven into the pole at a distance of 66-1/2" above the base.

So where did this pole come from? Chuck's home was once the home of the Agent who ran the canal-era Landing (cargo exchange point) in upper Merrimack, NH, i.e., at the river end of Depot Street in Reed's Ferry. Next to his property, many years ago (where a gas station now stands) there was a small warehouse that also belonged to the Landing, and from which the steering oar and the pike pole, now on display in the M'sex Canal Museum, were obtained This 'pole' came from the same building, thus the suspicion that it too was used for some purpose on the canal.

Chuck, Fred and I discussed a number of things that the pole might have been used for, some of them rather "farout"; then thought about our ideas, did some research, deliberated, corresponded a bit, and finally it was Fred who came up with the most rational hypothesis.

Rather than announce our hypothesis, I played "show and tell" with the pole at a recent meeting of the MCA BoD to solicit the thoughts of the members. Two BoD members decided that the pole was some sort of mast, but they were confused because it was not tall enough to carry a sail. So, could it have been a mast? And if so, how was it used?

Would you care to venture a guess? When you've thought about it and think you might know, you can compare your thoughts with ours, near the back page of this issue! If you had a different idea, I'd really like to hear from you because we really don't actually KNOW what the pole is either.

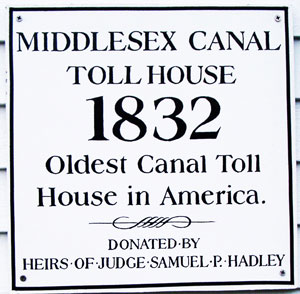

A FACELIFT FOR THE TOLL HOUSE

by Bill Gerber

In the photo above, all decked out for Christmas, is the 1832 Middlesex Canal Toll House, said to be the oldest such toll house in the country. It's sited opposite the central fire station along North Road, at the northeast corner of Chelmsford Common.

The good news is that the town is taking pretty good care of it. The bad news is that not very many people know what it is, how it was used, or about the ambitious enterprise that it once was part of. In recent times, in one local newspaper, I've even seen it referred to as the Middlesex Turnpike's toll house. Ouch, that hurts! In the meantime, Chelmsford is pretty much using it for a garden shed, and sight of it from the road is partially blocked by utility cabinets, park benches and a trash compactor.

The good news is that the town is taking pretty good care of it. The bad news is that not very many people know what it is, how it was used, or about the ambitious enterprise that it once was part of. In recent times, in one local newspaper, I've even seen it referred to as the Middlesex Turnpike's toll house. Ouch, that hurts! In the meantime, Chelmsford is pretty much using it for a garden shed, and sight of it from the road is partially blocked by utility cabinets, park benches and a trash compactor.

In the March 2002, issue of Towpath Topics (http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath/), Jane Drury wrote about an earlier 'facelift'. At that time Jane included quite a lot of information about the history of the building and how it found its way to Chelmsford Common. She noted that it had been moved five times since it was built, but delightfully, it's still in the same location today; perhaps it has finally found a permanent home.

The Toll House originally stood near the top of the Merrimack flight of locks, on the West side of the canal and just to the north of Chelmsford Landing.

This flight was a three-lock staircase that lifted or lowered boats between the Merrimack River and the Concord River level of the canal.

One of the reasons the Toll House may still be in the same place is that it seems to be tethered to the earth around it by modern functions. The cluster of photos below show connections to buried electrical, communications and plumbing fixtures on three of its four sides.

The photos below sample the interior of the Toll House as it appeared this summer. It was pretty unkempt and badly in need of painting. The painting has yet to be completed, but a recent peek through the window suggests that the contents have been "tidied up" considerably; it looks a lot neater inside. Nevertheless, the Toll House is still being used much like a garden shed - to store Christmas decorations and, in the summer, accoutrements of the Chelmsford Band.

Surely we can do better with it than this. Couldn't we find some way for the Toll House to fulfill some sort of educational purpose, consistent with the history of the Middlesex Canal and particularly the role of the toll house in the operation thereof?

THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

by Lorin L. Dame A. M. 1884

[This is one of the more comprehensive articles by an early historian, describing the Middlesex Canal that I've found. The article is quite good, if you haven't read it, I recommend it to you. I've included it here principally to place it among our own archives. The author's original spelling has been retained throughout. - BG]

The curious traveller may still trace with little difficulty the line of the old Middlesex canal, with here and there a break, from the basin at Charlestown to its junction with the Merrimac at Middlesex village. Like an accusing ghost, it never strays far from the Boston & Lowell Railroad, to which it owes its untimely end.

At Medford, the Woburn sewer runs along one portion of its bed, the Spot pond water-pipes another. The tow-path, at one point, marks the course of the defunct Mystic Valley Railroad; at others, it has been metamorphosed into sections of the highway; at others, it survives as a cow-path or woodland lane; at Wilmington, the stone sides of a lock have become the lateral walls of a dwelling-house cellar.

Judging the canal by the pecuniary recompense it brought its projectors, it must be admitted a dismal failure; yet its inception was none the less a comprehensive, far-reaching scheme, which seemed to assure a future of ample profits and great public usefulness. Inconsiderable as this work may appear compared with the modern achievements of engineering, it was, for the times, a gigantic undertaking, beset with difficulties scarcely conceivable to-day. Boston was a small town of about twenty thousand inhabitants; Medford, Woburn, and Chelmsford were insignificant villages; and Lowell was as yet unborn, while the valley of the Merrimac, northward into New Hampshire, supported a sparse agricultural population. But the outlook was encouraging. It was a period of rapid growth and marked improvements.

The subject of closer communication with the interior early became a vital question. Turnpikes, controlled by corporations, were the principal avenues over which country produce, lumber, firewood, and building-stone found their way to the little metropolis. The cost of entertainment at the various country inns, the frequent tolls, and the inevitable wear and tear of teaming, enhanced very materially the price of all these articles. The Middlesex canal was the first step towards the solution of the problem of cheap transportation. The plan with the Hon. James Sullivan, who was for six years a judge of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, attorney general from 1790 to 1807, and governor in 1807 and 1808, dying while holding the latter office.

A brief glance at the map of the New England States will bring out in bold relief the full significance of Sullivan's scheme. It will be seen that the Merrimac river, after pursuing a southerly course as far as Middlesex village, turns abruptly to the north-east. A canal from Charlestown mill-pond to this bend of the river, a distance of 27-1/4 miles, would open a continuous water-route of eighty miles to Concord, N.H. From this point, taking advantage of Lake Sunapee, a canal could easily be run in a northwesterly direction to the Connecticut [River] at Windsor, Vt.; and thence, making use of intermediate streams, communication could be opened with the St. Lawrence.

The speculative mind of Sullivan dwelt upon the pregnant results that must follow the connection of Boston with New Hampshire and possibly Vermont and Canada. He consulted his friend, Col. Baldwin, sheriff of Middlesex, who had a natural taste for engineering, and they came to the conclusion that the plan was feasible. Should the undertaking succeed between Concord and Boston, the gradual increase in population and traffic would in time warrant the completion of the programme [sic]. Even should communication never be established beyond Concord, the commercial advantages of opening to the market the undeveloped resources of upper New Hampshire would be a sufficient justification.

Accordingly, James Sullivan, Loammi Baldwin, Jonathan Porter, Samuel Swan, and five members of the Hall family at Medford, petitioned the General Court for an act of incorporation. A charter was granted, bearing date of June 22, 1793, "incorporating James Sullivan, Esq., and others, by the name of the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal," and on the same day was signed by His Excellency John Hancock, Governor of the Commonwealth. By this charter the proprietors were authorized to lay such assessments from time to time as might be required for the construction of the canal.

At their first meeting the proprietors intrusted the management of the corporation to a board of thirteen members, who were to choose a president and vice-presidents from their own number, the entire board subject to annual election. Boston capitalists subscribed freely, and Russell, Gore, Barrell, Craigie, and Brooks appear among the earliest directors. This board organized on the 11th of October by the choice of James Sullivan as president, and Col. Baldwin and John Brooks (afterwards Gov. Brooks) as vice-presidents.

The first step was to make the necessary surveys between the Charlestown basin and the Merrimac at Chelmsford; but the science of engineering was in its infancy, and it was difficult to find a competent person to undertake the task. At length Samuel Thompson, of Woburn, was engaged to make a preliminary survey.

Not wholly satisfied with [Thompson's] report, the directors afterwards secured the services of [William] Weston, an eminent English engineer, then employed in Pennsylvania on the [Schuylkill and Union] canals. His report, made Aug. 2, 1794, was favorable; and it is interesting to compare his figures with those of Mr. Thompson. As calculated by Thompson, the ascent from Medford bridge to the Concord river, at Billerica, was found to be 68-1/2 ft.; the actual difference in level, as found by Weston, was 104 ft. By Thompson's survey there was a further ascent of 16-1/2 ft. to the Merrimac; when, in fact, the water at Billerica bridge is almost 25 ft. above the Merrimac at Chelmsford.

Col. Baldwin, who superintended the construction of the canal, removed the first turf, Sept. 10, 1794. The progress was slow and attended with many embarrassments. The purchase of land from more than one hundred proprietors demanded skilful diplomacy. Most of the lands used for the canal were acquired by voluntary sale, and conveyed in fee-simple to the corporation. Sixteen lots were taken under authority of the Court of Sessions; while for thirteen neither deed nor record could be found when the corporation came to an end. Some of the land was never paid for, as the owner refused to accept the sum awarded. The compensation ranged from about $150 an acre in Medford to $25 in Billerica. The numerous conveyances are all in Sullivan's handwriting.

Labor was not easily procured, probably from the scarcity of laborers, as the wages paid, $10 a month and board, were presumably as much as could be earned in manual labor elsewhere. "An order was sent to England for a levelling instrument made by [Troughton], of London, and this was the only instrument used for engineering purposes after the first survey by Weston." Two routes were considered; forty years later, the rejected route was selected for the Lowell Railroad.

The canal, 30 ft. wide, [3.5] ft. deep, with 20 locks, [8] aqueducts, and crossed by 50 bridges, was, in [1803], sufficiently completed for the admission of water, and the following year was opened to public navigation from the Merrimac to the Charles. Its cost, about $500,000, of which one third was for land damages, was but little more than the estimate.

Commencing at Charlestown mill-pond, it passed through Medford, crossing the Mystic by a wooden aqueduct of 100 ft., to Horn pond in Woburn. Traversing Woburn and Wilmington it crossed the Shawshine by an aqueduct of 137 ft., and struck the Concord, from which it receives its water, at Billerica Mills. Entering the Concord by a stone guard-lock, it crossed, with a floating tow-path, and passed out on the northern side through another stone guard-lock; thence it descended 27 ft., in a course of 5-1/4 miles, through Chelmsford to the Merrimac, making its entire length 27-1/4 m. [Correction: The canal remained level over the 5-1/4 miles from the Concord River to Middlesex Village, where it descended the 27 feet to the Merrimack River via a three-lock staircase. - Ed]

The proprietors made Charlestown bridge the eastern terminus for their boats, but ultimately communication was opened with the markets and wharves upon the harbor, through Mill Creek, over a section of which Blackstone street now extends.

As the enterprise had the confidence of the business community, money for prosecuting the work had been procured with comparative ease. The stock was divided into 800 shares, and among the original stockholders appear the names of Ebenezer and Dudley Hall, Oliver Wendall, John Adams of Quincy, Peter C. Brooks of Medford, and Andrew Craigie of Cambridge. The stock had steadily advanced from $25 a share in the autumn of 1794 to $473 in 1803, the year the canal was opened, touching $500 in 1804. Then a decline set in, a few dollars at a time, till 1816, when its market value was $300 with few takers, although the canal was in successful operation, and, in 1814, the obstructions in the Merrimac had been surmounted, so that canal boats, locking into the river at Chelmsford, had been poled up stream as far as Concord.

Firewood and lumber always formed a very considerable item in the business of the canal. The navy-yard at Charlestown and the shipyards on the Mystic for many years relied upon the canal for the greater part of the timber used in shipbuilding; and work was sometimes seriously retarded by low water in the Merrimac, which interfered with transportation. The supply of oak and pine about Lake Winnipiseogee, and along the Merrimac and its tributaries, was thought to be practically inexhaustible. In the opinion of Daniel Webster, the value of this timber had been increased $5,000,000 by the canal. Granite from Tyngsborough, and agricultural products from a great extent of fertile country, found their way along this channel to Boston; while the return boats supplied taverns and country stores with their annual stock of goods. The receipts from tolls, rents, etc. were steadily increasing, amounting,

in 1812 to $12,600 " 1813 " 16,800 " 1814 " 25,700 " 1815 " 29,200 " 1816 " 32,600

Yet, valuable, useful, and productive as the canal had proved itself, it had lost the confidence of the public, and, with a few exceptions, of the proprietors themselves. The reason for this state of sentiment can easily be shown. The general depression of business on account of the embargo and the war of 1812 had its effect upon the canal. In the deaths of Gov. Sullivan and Col. Baldwin, in the same year, 1808, the enterprise was deprived of the wise and energetic counsellors to whom it owed its existence.

The aqueducts and most of the locks, being built of wood, required large sums for annual repairs; the expenses arising from imperfections in the banks, and from the erection of toll-houses and public houses for the accommodation of the boatmen, were considerable; but the heaviest expenses were incurred in opening the Merrimac for navigation. From Concord, N.H., to the head of the canal the river has a fall of 123 ft., necessitating various locks and canals. The Middlesex Canal Corporation contributed to the building of the Wiccasee locks and canals, $12,000; Union locks and canals, $49,932; Hookset canal, $6,750; Bow canal and locks, $14,115, making a sum total of $82,797 to be paid from the income of the Middlesex canal.

The constant demand for money in excess of the incomes had proved demoralizing. Funds had been raised from time to time by lotteries. In the Columbian "Centinel & Massachusetts Federalist" of Aug. 15, 1804, appears an advertisement of the Amoskeag Canal Lottery, 6,000 tickets at $5, with an enumeration of prizes. The committee, consisting of Phillips Payson, Samuel Swan, Jr., and Loammi Baldwin, Jr., appealed to the public for support, assuring the subscribers that all who did not draw prizes would get the full value of their money in the reduced price of fuel.

In 1816 the Legislature of Massachusetts granted the proprietors of the canal, in consideration of its usefulness to the public, two townships of land in the district of Maine, near Moosehead lake. This State aid, however, proved of no immediate service, as purchasers could not be found for several years for property so remote. Appeals to capitalists, lotteries, and State aid proved insufficient; the main burden fell upon the stockholders. In accordance with the provisions of the charter, assessments had been levied, as occasion required, up to 1816, 99 in number, amounting to $670 per share; and the corporation was still staggering under a debt of $64,000. Of course, during all this time, no dividends could be declared.

Under these unpromising conditions a committee, consisting of Josiah Quincy, Joseph Hall, and Joseph Coolidge, Jr., was appointed to devise the appropriate remedy. "In the opinion of your committee," the report reads, "the real value of the property, at this moment, greatly exceeds the market value, and many years will not elapse before it will be considered among the best of all practicable monied investments. The Directors contemplate no further extension of the canal. The work is done, both the original and subsidiary canals.... Let the actual incomes of the canal be as great as they may, so long as they are consumed in payment of debts and interest on loans, the aspect of the whole is that of embarrassment and mortgage. The present rates of income, if continued, and there is every rational prospect, not only of its continuance, but of its great and rapid increase, will enable the corporation—when relieved of its present liabilities,—at once to commence a series of certain, regular, and satisfactory dividends." They accordingly recommended a final assessment of $80 per share, completely to extinguish all liabilities. This assessment, the 100th since the commencement, was levied in 1817, making a sum total of $600,000, extorted from the long-suffering stockholders. If to this sum the interest of the various assessments be added, computed to Feb. 1, 1819, the date of the first dividend, the actual cost of each share is found to have been $1,455.25.

The prosperity of the canal property now seemed fully assured. The first dividend, though only $15, was the promise of golden showers in the near future, and the stock once more took an upward flight. From 1819 to 1836 were the palmy days of the canal, unvexed with debts, and subject to very moderate expenses for annual repairs and management.

It is difficult to ascertain the whole number of boats employed at any one time. Many were owned and run by the proprietors of the canal; and many were constructed and run by private parties who paid the regular tolls for whatever merchandise they transported. Boats belonging to the same parties were conspicuously numbered, like railway cars to-day. From "Regulations relative to the Navigation of the Middlesex Canal," a pamphlet published in 1830, it appears that boats were required to be not less than 40 ft. nor more than 75 ft. in length and not less than 9 ft. nor more than 9-1/2 ft. in width. Two men, a driver and steersman, usually made up the working force; the boats, however, that went up the Merrimac required three men, one to steer, and two to pole. The Lowell boats carried 20 tons of coal; 15 tons were sufficient freight for Concord; when the water in the Merrimac was low, not more than 6 or 7 tons could be taken up the river. About 1830 the boatmen received $15 per month.

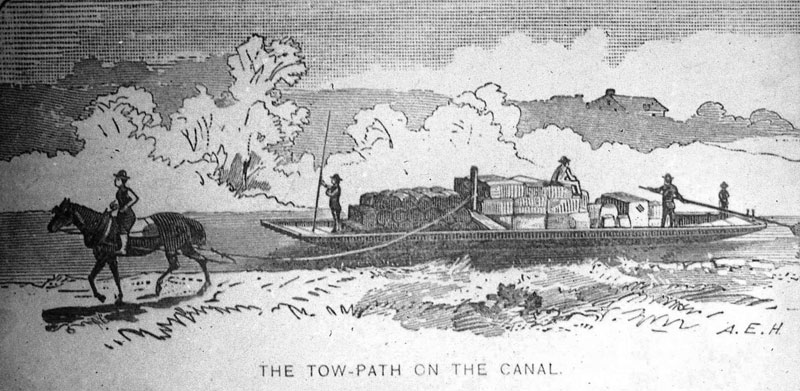

Lumber was transported in rafts of about 75 ft. long and 9 ft. wide; and these rafts, not exceeding ten in number, were often united in "bands." A band of seven to ten rafts required the services of five men, including the driver. Boats were drawn by horses, and lumber by oxen; and "luggage boats" were required to make two and a half miles an hour, while "passage boats" attained a speed of four miles. Boats of the same class, and going the same way, were not allowed to pass each other, thus making "racing" impossible on the staid waters of the old canal. Whenever a boat approached a lock, the conductor sounded his horn to secure the prompt attention of the lock-tender; but due regard was paid to the religious sentiment of New England. Travelling in the canal being permitted on Sundays, "in consideration of the distance from home at which those persons using it generally are, it may be reasonably expected that they should not disturb those places of public worship near which they pass, nor occasion any noise to interrupt the tranquillity of the day. Therefore, it is established that no Signal-Horn shall be used or blown on Sundays."

The tariff varied greatly from year to year. In 1827 the rate from Lowell to Boston was $2.00 the gross ton; but many articles were carried on much lower terms.

On account of liability of damage to the banks of the canal, all navigation ceased at dark; hence a tavern was established at every lock, or series of locks. These were all owned by the corporation, and were often let to the lock-tender, who eked out his income by the accommodation of boatmen and horses. The Bunker Hill Tavern, in Charlestown, situated so as to accommodate both county and canal travel, was leased, in 1830, for $350; in 1838, it let for $500. The Horn Pond House, at Woburn, in 1838, was leased for $700. In 1825, a two-story dwelling-house, 36 X 18, built at a cost of $1,400, for the accommodation of boatmen and raftsmen, at Charlestown, rented, with stable attached, for $140. In all these cases, the real estate was supposed to pay ten per cent.

Some of these canal-taverns established a wide reputation for good cheer, and boatmen contrived to be overtaken by night in their vicinity. Sometimes fifteen or twenty boats would be detained at one of these favorite resorts, and a jolly crowd fraternized in the primitive bar-room. The temperance sentiment had not yet taken a firm hold in New England. "Flip" was the high-toned beverage of those days; but "black-strap," a compound of rum and molasses, sold at three cents a glass, was the particular "vanity" of the boatmen. In the smaller taverns, a barrel of old Medford, surmounted by a pitcher of molasses, scorning the flimsy subterfuges of modern times, boldly invited its patrons to draw and mix at their own sweet will. "Plenty of drunkenness, Uncle Joe, in those days?" we queried of an ancient boatman who was dilating upon the good old times. "Bless your heart, no!" was the answer. "Mr. Eddy didn't put up with no drunkards on the canal. They could drink all night, sir, and be steady as an eight-day clock in the morning."

When the feverish haste born of the locomotive and telegraph had not yet infected society, a trip over the canal in the passenger-packet, the "Governor Sullivan," must have been an enjoyable experience. Protected by iron rules from the dangers of collision; undaunted by squalls of wind, realizing, should the craft be capsized, that he had nothing to do but walk ashore, the traveller, speeding along at the leisurely pace of four miles per hour, had ample time for observation and reflection. Seated, in summer, under a capacious awning, he traversed the valley of the Mystic skirting the picturesque shores of Mystic pond. Instead of a foreground of blurred landscape, vanishing, ghostlike, ere its features could be fairly distinguished, soft bits of characteristic New England scenery, clear cut as cameos, lingered caressingly on his vision; green meadows, fields riotous with blossomed clover, fragrant orchards, and quaint old farmhouses, with a background of low hills wooded to their summits.

Passing under bridges, over rivers, between high embankments, and through deep cuttings, floated up hill by a series of locks, he marvelled at this triumph of engineering, and, if he were a director, pictured the manufactories that were to spring up along this great thoroughfare, swelling its revenues for all time.

The tow-path of the canal was a famous promenade. Upon Sunday afternoons, especially, numerous pedestrians from the dusty city strolled along the canal for a breath of fresh air and a glimpse of the open country, through the Royal estate in Medford, past the substantial old-fashioned mansion-house of Peter C. Brooks, as far, perhaps, as the Baldwin estate, and the birthplace of Count Rumford, in Woburn. "I love that old tow-path," said Uncle Joe. "'Twas there I courted my wife; and every time the boat went by she came tripping out to walk a piece with me! Bless you, sir the horses knew her step, and it wan't so heavy, nuther."

Meanwhile, under the direction of Caleb Eddy, who assumed the agency of the corporation in 1825, bringing great business ability and unquenchable zeal to his task, the perishable wooden locks were gradually replaced with stone, a new stone dam was built at Billerica, and the service brought to a high state of efficiency. The new dam was the occasion of a lawsuit brought by the proprietors of the Sudbury meadows, claiming damages to the extent of $10,000 for flooding their meadows. The defendants secured the services of Samuel Hoar, Esq., of Concord, assisted by the Hon. Daniel Webster, who accepted a retaining fee of $100 to "manage and argue the case in conjunction with Mr. Hoar. The cause was to have been tried November, 1833. Mr. Webster was called on by me and promised to examine the evidence and hold himself in readiness for the trial, but for some time before he was not to be found in Boston, at one time at New York, at another in Philadelphia, and so on from place to place so that I am satisfied no dependance can be placed with certainty upon his assistance, and," plaintively concludes the agent, "our $100 has gone to profit and loss account."

On the other side was the Hon. Jeremiah Mason, assisted by Franklin Dexter, Esq. This case was decided the following year adversely to the plaintiffs.

With the accession of business brought by the corporations at Lowell, the prospect for increased dividends in the future was extremely encouraging. The golden age of the canal appeared close at hand; but the fond hopes of the proprietors were once more destined to disappointment. Even the genius of James Sullivan had not foreseen the railway locomotive. In 1829 a petition was presented to the Legislature for the survey of a railroad from Boston to Lowell. The interests of the canal were seriously involved. A committee was promptly chosen to draw up for presentation to the General Court "a remonstrance of the Proprietors of Middlesex Canal, against the grant of a charter to build a railroad from Boston to Lowell." This remonstrance, signed by William Sullivan, Joseph Coolidge, and George Hallett, bears date of Boston, Feb. 12, 1830, and conclusively shows how little the business men of fifty years ago anticipated the enormous development of our resources consequent upon the application of steam to transportation:—

The remonstrants take pleasure in declaring, that they join in the common sentiment of surprise and commendation, that any intelligence and enterprise should have raised so rapidly and so permanently, such establishments as are seen at Lowell. The proprietors of these works have availed themselves of the canal, for their transportation for all articles, except in the winter months ... and every effort has been made by this corporation to afford every facility, it was hoped and believed, to the entire satisfaction of the Lowell proprietors. The average annual amount of tolls paid by these proprietors has been only about four thousand dollars. It is believed no safer or cheaper mode of conveyance can ever be established, nor any so well adapted for carrying heavy and bulky articles. To establish therefore a substitute for the canal alongside of it, and in many places within a few rods of it, and to do that which the canal was made to do, seems to be a measure not called for by any exigency, nor one which the Legislature can permit, without implicitly declaring that all investments of money in public enterprises must be subjected to the will of any applicants who think that they may benefit themselves without regard to older enterprises, which have a claim to protection from public authority. With regard, then, to transportation of tonnage goods, the means exist for all but the winter months, as effectually as any that can be provided.

There is a supposed source of revenue to a railroad, from carrying passengers. As to this, the remonstrants venture no opinion, except to say, that passengers are now carried, at all hours, as rapidly and safely as they are anywhere else in the world.... To this, the remonstrants would add, that the use of a railroad, for passengers only, has been tested by experience, nowhere, hitherto; and that it remains to be known, whether this is a mode which will command general confidence and approbation, and that, therefore, no facts are now before the public, which furnish the conclusion, that the grant of a railroad is a public exigency even for such a purpose. The Remonstrants would also add, that so far as they know and believe, "there never can be a sufficient inducement to extend a railroad from Lowell westwardly and northwestwardly, to the Connecticut, so as to make it the great avenue to and from the interior, but that its termination must be at Lowell" (italics our own), "and, consequently that it is to be a substitute for the modes of transportation now in use between that place and Boston, and cannot deserve patronage from the supposition that it is to be more extensively useful...."

The Remonstrants, therefore, respectfully submit: First, that there be no such exigency as will warrant the granting of the prayer for a railroad to and from Lowell.

Secondly, that, if that prayer be granted, provision should be made as a condition for granting it, that the Remonstrants shall be indemnified for the losses which will be thereby occasioned to them.

This may seem the wilful blindness of self-interest; but the utterances of the press and the legislative debates of the period are similar in tone. In relation to another railroad, the "Boston Transcript" of Sept. 1, 1830, remarks: "It is not astonishing that so much reluctance exists against plunging into doubtful speculations.... The public itself is divided as to the practicability of the Rail Road. If they expect the assistance of capitalists, they must stand ready to guarantee the percentum per annum; without this, all hopes of Rail Roads are visionary and chimerical." In a report of legislative proceedings published in the "Boston Courier," of Jan. 25, 1830, Mr. Cogswell, of Ipswich, remarked: "Railways, Mr. Speaker, may do well enough in old countries, but will never be the thing for so young a country as this. When you can make the rivers run back, it will be time enough to make a railway." Notwithstanding the pathetic remonstrances and strange vaticinations of the canal proprietors, the Legislature incorporated the road and refused compensation to the canal. Even while the railroad was in process of construction, the canal directors do not seem to have realized the full gravity of the situation. They continued the policy of replacing wood with stone, and made every effort to perfect the service in all its details; as late as 1836 the agent recommended improvements. The amount of tonnage continued to increase—the very sleepers used in the construction of the railway were boated, it is said, to points convenient for the workmen. In 1832 the canal declared a dividend of $22 per share; from 1834 to 1837, inclusive, a yearly dividend of $30.

The disastrous competition of the Lowell Railroad was now beginning to be felt. In 1835 the Lowell goods conveyed by canal paid tonnage dues of $11,975.51; in 1836 the income from this source had dwindled to $6,195.77. The canal dividends had been kept up to their highest mark by the sale of its townships in Maine and other real estate: but now they began to drop. The year the Lowell road went into full operation the receipts of the canal were reduced one-third; and when the Nashua & Lowell road went into full operation, in 1840, they were reduced another third. The board of directors waged a plucky warfare with the railroads, reducing the tariff on all articles, and almost abolishing it on some, till the expenditures of the canal outran its income; but steam came out triumphant. Even sanguine Caleb Eddy became satisfied that longer competition was vain, and set himself to the difficult task of saving fragments from the inevitable wreck.

At this time (1843) Boston numbered about 100,000 inhabitants, and was dependent for water upon cisterns and wells. The supply of water in the wells had been steadily diminishing for years, and what remained was necessarily subject to contamination from numberless sources. "One specimen which I analyzed," said Dr. Jackson, "which gave three per cent, of animal and vegetable putrescent matter, was publicly sold as a mineral water; it was believed that water having such a remarkable fetid odor and nauseous taste, could be no other than that of a sulphur spring; but its medicinal powers vanished with the discovery that the spring arose from a neighboring drain." Here was a golden opportunity. Eddy proposed to abandon the canal as a means of transportation, and convert it into an aqueduct for supplying the City of Boston with wholesome water. The sections between the Merrimac and Concord at one extremity, and Charlestown mill-pond and Woburn at the other, were to be wholly discontinued. Flowing along the open channel of the canal from the Concord river to Horn-pond locks in Woburn, from thence it was to be conducted in iron pipes to a reservoir upon Mount Benedict in Charlestown, a hill eighty feet above the sea-level.

The good quality of the Concord-river water was vouched for by the "analysis of four able and practical chemists, Dr. Charles T. Jackson, of Boston; John W. Webster, of Cambridge University; S.L. Dana, of Lowell, and A.A. Hayes, Esq., of the chemical works at Roxbury." The various legal questions involved were submitted to the Hon. Jeremiah Mason, who gave an opinion, dated Dec. 21, 1842, favorable to the project. The form for an act of incorporation was drawn up; and a pamphlet was published, in 1843, by Caleb Eddy, entitled an "Historical sketch of the Middlesex Canal, with remarks for the consideration of the Proprietors," setting forth the new scheme in glowing colors.

But despite the feasibility of the plan proposed, and the energy with which it was pushed, the agitation came to naught; and Eddy, despairing of the future, resigned his position as agent in 1845. Among the directors during these later years were Ebenezer Chadwick, Wm. Appleton, Wm. Sturgis, Charles F. Adams, A.A. Lawrence, and Abbott Lawrence; but no business ability could long avert the catastrophe. Stock fell to $150, and finally the canal was discontinued, according to Amory's Life of Sullivan, in 1846. It would seem, however, that a revival of business was deemed within the range of possibilities, for in conveyances made in 1852 the company reserved the right to use the land "for canalling purposes"; and the directors annually went through with the form of electing an agent and collector as late as 1853.

"Its vocation gone, and valueless for any other service," says Amory, "the canal property was sold for $130,000. After the final dividends, little more than the original assessments had been returned to the stockholders." Oct. 3, 1859, the Supreme Court issued a decree, declaring that the proprietors had "forfeited all their franchises and privileges, by reason of non-feasance, non-user, misfeasance and neglect." Thus was the corporation forever extinguished.

WHAT COULD IT HAVE BEEN USED FOR?

(continued from earlier in this issue)

None of us had anything overt to tell us what the pole was or how it was used, and thus several possibilities were considered. One of the more likely lines of thinking was that it could have been a 'spoke' for some sort of capstan; but we have no indication of the use of any such device, also, we couldn't come up with any mode of usage that would account for the wear and deterioration patterns on the pole.

An 'educated guess' converged on by Fred Lawson, Chuck Mower, myself, and later by Tom Raphael and Tom Dahill, is that, most likely, the pole is some sort of mast, but, confusingly, it was way-too-short to carry a sail. Eventually Fred realized, and has pretty well convinced the rest of us, that it may well have been a towing mast such as would have been used for towing a freight boat up and down the Middlesex Canal, and possibly whenever the boat was assisted through any of the river canals.

So, how did Fred come to this conclusion? Judge Samuel Hadley was intimately familiar with the canal - when he was a child he played along it, when a young man he was employed by it, and late in his life he wrote an extensive paper about growing up in M'sex Village. At some time in his youth, Judge Hadley built a model of a freight boat, which still existed in the 1930s when Leon Cutler took the picture shown above. (Where is it now, I wonder?) In the photo, the towing mast can be seen near the center of Hadley's model, i.e., the mast to which the towline was attached, and it's tied at a point just high enough to clear the load.

Though I don't know the sources of his information, Alan Evans (A.E.) Herrick, who's illustrations of canal boats appear in McClintock's History of New Hampshire (published in 1889), as well as in publications of Lowell's Old Residents' Historical Association, shows detail similar to that provided by Judge Hadley. His drawing "The Towpath on the Canal" is shown above. In it Herrick also shows a mast, supported by a thwart, to which the towline is attached.

On all such freight boats (aka luggage boats) the foot of the mast would have passed through a square hole in a mast-thwart at gunwale (aka "gunnel") level and been seated into a step, i.e., a receptacle on the inside of the hull, well anchored to the hull and probably to a reinforced rib. This assembly would have been located slightly forward of the fore-aft center of the boat to ease steering while under tow.

Given that the bottom of the boat, and the step, was often wet, and therefore the post/mast was subjected to repeated wet-dry cycles, this likely accounts for the dry-rot at the square end, i.e., at the foot of the mast.

It's not likely that there was ever a great amount of tension on the mast, enough to have caused it to bow - perhaps a bit when the boat started moving but thereafter a steady but not great tension, only enough to sustain speed. This might account for the very slight compression of the wood above the foot of the mast, likely at the level of the mast thwart through which it passed.

That there were multiple tie points on the post/mast might simply reflect the various heights at which the towline was attached, typically at a point chosen to clear the height of the loads carried, whatever they may have been.

But why use a mast? Why not just attach the towline to a cleat or similar fixture on either side of the boat?

On the luggage boats, it would have been more convenient to use the towing mast for several reasons. As noted, the mast would have allowed the towline to be attached at whatever height was necessary to clear the height of the load carried. Also, it would have allowed the line of the towline to vary widely in angle, as when the line was slacked and sunk to enable passage by other boats, as well as to change when the towpath shifted from one side of the channel to the other. (See "Which side … " in the March 2008 issue of Towpath Topics, available at http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath/.) With the towline free to swing, unobstructed, from one side of the boat to the other, there would have been little need to detach it, perhaps only when passing through a lock, and even this being less likely when downward-bound. (Why would this be so?)

The towline may well have been attached to cleats on either side of Packet Boat hulls, simply to keep the upper deck (where people sometimes sat) clear of any obstructions, and it would not have been desirable to have a mast hole perforating the roof. But this practice would have increased the risk that the line might be dropped when it was necessary to switch it from one side to the other. Since Packets usually had priority on the canal, there would have been less frequent need to slack the line to allow passage by another boat.

That our pole/mast was, in fact, a towing mast seems a most likely and defendable conclusion. It's for this reason that Chuck Mower is making it available to us on an indefinite loan, and it will be added to the artifacts on display in our museum.

MISCELLANY

Estate Planning - To those of you who are making your final arrangements, please remember the Middlesex Canal Association. Your help is vital to our future. Thank you for considering us.

Web Site - As you may have noted in the nameplate, www.middlesexcanal.org is the URL for the Middlesex Canal Association's web site. Our webmaster, Robert Winters, keeps the site up to date, thus events and sometimes articles and other information will sometimes appear there before we can get it to you through Towpath Topics. Please do check the site from time to time for new entries. Also, the site now contains a valuable repository of historical information, all of the back issues of TT, and an index to all of the articles contained therein, can now be found there at http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath/.

Museum & Reardon Room Rental - The facility is available at very reasonable rates for private affairs, and for non-profit organizations' meetings. The conference room holds up to 60 people and includes access to a kitchen and rest rooms. For details and additional information please contact the museum at 978-670-2740.

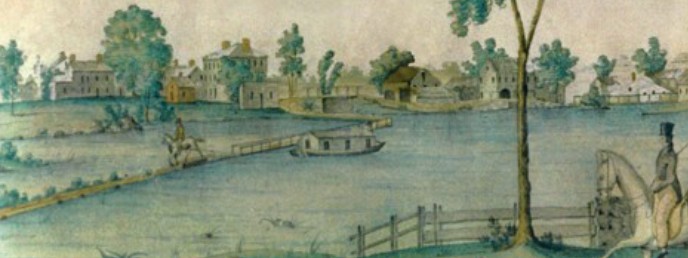

Nameplate - Excerpt from a watercolor painted by Jabez Ward Barton, ca. 1825, entitled "View from William Rogers House". Shown, looking west, may be the packet boat George Washington being towed across the Concord River from the Floating Towpath at North Billerica.

Back Page - Excerpt from an August,1818, drawing (artist unknown) of the Steam Towboat Merrimack crossing the original (pre-1829) Medford Aqueduct.

Canal Game and Puzzle - The National Canal Museum has made a canal related game and a puzzle available on their web site www.canals.org/funandgames/. These include: a Boat Captain's Game - Can you run a canal shipping business successfully? And a Canal Lock Puzzle - would you know how to construct a canal lock and make it work? Give them a try.

Towpath Topics is edited and published by Bill Gerber and Robert Winters.

Corrections, contributions, and ideas for future issues are always welcome.