Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 57 No. 3 | May 2019 |

Please mark your calendars

MCA Sponsored Events

2019 Schedule

Spring Meeting

1:00pm, Sunday, May 5, 2019

Annual Meeting

Earl Taylor, President of the Dorchester Historical Society,

His presentation will be on the topic of “Tide Mills”

17th Annual Bicycle Tour North

9:00am, Saturday, October 5, 2019

Fall Walk

1:30pm, Sunday, October 20, 2019

Billerica-Chelmsford

Fall Meeting

1:00pm, Sunday, October 27, 2019

Speaker TBA

The Visitor/Center Museum is open Saturday and Sunday, noon – 4pm, except on holidays. The Board of Directors meets the 1st Wednesday of each month, 3:30-5:30pm, except July and August.

Visit www.middlesexcanal.org for up-to-date listings of MCA events and other events of interest to canallers!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

President’s Message by J. Breen

‘The son of the Middlesex Canal, “The Other Canal” i.e. The Erie Canal’ by Howard Winkler

“The Boston and Lowell Railroad in 1835” by Larz F. Neilson

“Presentation about Tide Mills from Revere to Quincy, 2019” by Earl Taylor

Miscellany

MCA Officers & Directors: 2018-2019

Editors’ Letter

Dear Readers,

This issue finds us waiting for spring, after a not-too-bad winter, with daffodils and forsythia leading the way, as they always do in April. Good reading material will keep you busy on the rainy days, and there are many articles here that should hold your attention.

Our feature article was written by Earl Taylor from the Dorchester Historical Society. Earl will be the featured speaker at the MCA Spring Meeting on May 5th at the MCA Museum and Visitors’ Center Reardon Room. He is a new voice to Towpath Topics and his article and presentation on tide mills will offer a wider view perspective to our knowledge of canals.

Two other articles also give us a look at the world outside the Middlesex Canal. The first, by Treasurer Emeritus Howard Winkler, is on the organization of the Erie Canal song and his introduction to it, and the second is by Larz Neilson on the Boston and Lowell Railroad. All the articles fill-in the history going on “around the canal.”

Under “business as usual” we have a photograph from the MCA Winter Meeting, the President’s Message, and a heads-up on events through the fall. Enjoy!

Deb, Alec, and Robert

MCA Sponsored Events and Directions to Museum

Spring Meeting: On May 5, 2019 at 1:00pm the MCA will hold a public meeting in the at the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center’s Reardon Room located at 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862. Earl Taylor, has been the President of the Dorchester Historical Society since 2002. He earned his Master’s Degree in Library Science from Simmons College and served as a rare book cataloguer at the Boston Public Library and later the American Antiquarian Society. In 1983 he became the Assistant Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library, then Director of Library Systems at Boston College. In 1987 he switched careers to real estate and mortgages.

Earl has been a Dorchester resident since 1979. He was invited to join the Dorchester Historical Society in 2000, and the following year he became President. Faced with the huge collections at the Dorchester Historical Society including manuscripts, photographs, books, and more, Earl found it was not enough to store information in file cabinets for future reference, he needed a way to find information when desired. To that end he created and still maintains the website www.DorchesterAtheneum.org. devoted to Dorchester history.

Under his leadership the Dorchester Historical Society has raised over $1,000,000 for property repairs, plus another $250,000 toward the endowment. Faced with five buildings in depreciating condition --- which include the James Blake House (ca. 1661 --- Boston’s oldest surviving house), the Lemuel Clap House (1767), the William Clapp House (1806), and various outbuildings --- Earl suggested in 2005 that the Society should engage consultants to create a long-term plan for governance, activities, and property repairs. The result has been an overwhelming response from Dorchester stakeholders far and wide who contributed the money to complete the exterior renovations of all five of the Society’s buildings. So far, these projects have been recognized by two preservation awards from the Massachusetts Historical Commission and two from the Boston Preservation Alliance.

17th Annual Bicycle Tour North: On Saturday, October 5, 2019 riders are encouraged to meet at 9:00am at the Middlesex Canal plaque, Sullivan Square MBTA Station (1 Cambridge Street, Charlestown, MA 02019). The ride will follow the canal route for 38 miles to Lowell. There will be a stops for snacks at the Kiwanis Park across from the Baldwin Mansion (2 Alfred Street, Woburn, MA 01801 ~ 12:30pm) and for a visit to the Middlesex Canal Museum (71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862 ~ 3:00pm). The tour will arrive in Lowell in time for the 5:00pm train back to Boston. Riders are able to choose their own time to join or leave the tour by using the Lowell line which parallels the canal. The ride is easy for most cyclists. The route is pretty flat and the tour group will average about 5 mph. Steady rain cancels; helmets are required. For changes and update see www.middlesexcanal.org. It is anticipated that the tour will be led by Bill Kuttner and Dick Bauer.

Fall Walk: The Fall Walk will take place on Sunday, October 20, 2019. Participants are encouraged to meet at the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center (71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862) at 1:30 P.M. The 2½ hour walk will cover part of the Merrimack River branch of the canal in Billerica and Chelmsford, over about 3 to 4 miles of generally wooded terrain. Sites visited on the tour will include the recently restored guard lock, the anchor stone for the floating towpath that bridged the Concord River, and many stretches of the watered canal. The walk is jointly listed as a local walk of the Boston Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club and the MCA. It is anticipated that the walk will be co-led by Robert Winters and Marlies Henderson. For the latest information please refer to the MCA website, www.middlesexcanal.org.

Fall Meeting: On October 27, 2019 at 1:00pm. the MCA will hold a public meeting at the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center’s Reardon Room located at 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862. At the time of this publication a speaker has not been chosen. Please refer to the MCA website, www.middlesexcanal.org, for the latest information

Directions to Museum: 71 Faulkner Street in North Billerica MA.

By Car

From Rte. 128/95

Take Route 3 toward Nashua, to Exit 28 “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at the fork. After another ¼ mile, at the traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A (Boston Road). Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road (Talbot Avenue) which will put St. Andrew’s Church on your left. Go ¼ mile to a stop sign and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the bridge over the Concord River, where Old Elm Street becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond bridge. Watch out crossing the street!

From I-495

Take Exit 37, North Billerica, then south roughly 2 plus miles to the stop sign at Mt. Pleasant Street, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700’ and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street (Faulkner Street).

By Train

The Lowell Commuter line runs between Lowell and Boston’s North Station. From the station side of the tracks at North Billerica, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station Street and Faulkner Street on the right side.

President’s Message

by J. Breen

In April 2012, the Middlesex Canal Commission (Tom Raphael, executive chairman), asked Cummings One World for $100,000 in support of a park on the towpath and berm of a half mile of canal between Alfred and School Streets in Woburn. In May, One World granted the Commission $100,000. In Dec 2014, the Commission returned $80,000 to Cummings, what was unspent upto the time the Woburn Conservation Commission denied permission to build the park.

Every year since ConCom’s 2014 denial, the Middlesex Canal Association has applied for a $100,000 Cummings grant for work at 2 Old Elm Street, thinking $80,000 was already a given. Each year 100 grants of $100,000 are awarded. In 2017, the applicants in the first round numbered 597 with 223 invited to compete in the next round. Four times, 2015 - 2018, the Association has been rejected in the first round.

The Cummings Foundation awards $10 million each year through its $100K for 100 grant program. This place-based philanthropic initiative primarily supports nonprofits in the Massachusetts counties where the Foundation and its founders originally derived their funds and where staff and clients of the Cummings organization live – Middlesex, Essex, and Suffolk County. The foregoing is from the Foundation’s web page, emphasis added.

Puzzling that the Commonwealth’s Middlesex Canal Heritage Park between Boston and Lowell has not been supported by the location based grant program of the Cummings Foundation. The Middlesex Canal is the spine of Middlesex County, the highway on which its prosperity began.

John Hancock in 1793 signed the act incorporating the Middlesex Canal Company. He was the first proprietor of the Middlesex Canal. The canal was “the greatest work of the kind that has been completed in the United States.” So wrote Albert Gallatin, US Secretary of Treasury, in his 1808 report to Congress. The canal by connecting Boston with the Merrimack River would make possible by ease of transportation as far as Concord NH similar prosperity as New York City derived from the Hudson and Philadelphia from the Delaware. (The execrable roads had nothing of the slitheriness of a canal highway: a horse and wagon could haul two tons, a horse and canal boat twenty tons.)

As soon as the digging was completed in 1803, a glass factory was operating where the canal entered the Merrimack with boats bringing sand from New Jersey to be melted at 2,400 degrees by burning the forests of New Hampshire, floated to the factory as rafts on the river. Window glass was shipped for use at Monticello. The head of the canal at the Merrimack River became Lowell’s Middlesex Village.

Medford ship building, which built 400 ocean-going ships, and Medford’s rum distilleries used the canal for lumber and fuel from New Hampshire. Somerville’s brick kilns burned the forests of New Hampshire. Woburn’s tanneries were based where tanbark from New Hampshire was delivered by canal. Woburn’s Horn Pond developed as a playground for Boston with comfortable, convenient travel on the canal. Wilmington was a hop garden for the East Coast. Lowell was founded where tons of cotton could be transported inexpensively by canal, making Lowell the eighteenth largest city in the United States in 1840. In sum, the canal was the highway by which Middlesex County prospered.

The Middlesex Canal Association was founded in 1962 as the result of a rousing talk on the canal at an October 1961 meeting of the Billerica Historical Society. Since then the Middlesex Canal has been added to the National Register of Historic Places, Massachusetts has established a Middlesex Canal Commission with the goal of a Middlesex Canal Heritage Park, a link between Boston and Lowell National Historic Parks. The association has a 4400 sq. ft. visitor center at the summit pond of the canal at the Billerica Falls of the Concord River, open 100 days/year. The association has walks, co-sponsored by the Appalachian Mountain Club, talks, and bike tours of the canal each year. The J.M.R. Barker Foundation has supported the association with a $10,000 grant for a children’s educational program.

The Middlesex Canal Association celebrated in 2003 the bicentennial of completion of the Middlesex Canal, fourteen years before the Erie celebrated its beginning. For the 55 years since its founding, the Association volunteers have worked as prayed by the proprietors of the canal at the groundbreaking on the banks of the Concord River summit pond to “benefit present and all Future Generations.” Towpath Topics, the journal of the association, now at volume 57, is a record of the accomplishments of the volunteers of the association.

The Cummings Foundation should make a grant to the Middlesex Canal Association because the canal (1) made possible the prosperity of Middlesex County from John Hancock in 1793 up to the arrival of the iron horse in 1835; (2) the canal is in fact a place-based Middlesex County heritage park; (3) because the association should be honored for 57 years of walks, talks, and education for the public; and (4) to support its next half century of volunteers.

The Cummings Foundation favors grants to organizations serving limited groups within its place-based philanthropy. The Middlesex Canal Association serves all.

The Son of the Middlesex Canal, or the “Other Canal,” i.e The Erie Canal

by Howard Winkler

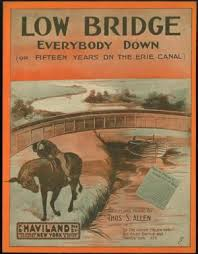

I had long thought that the Low Bridge, Everybody Down song about the Erie Canal was of indigenous origin, written by a backwoods troubadour who adapted an old English or Welsh tune. This thinking was dispelled when I searched the Internet and found that the words and music were written in 1913 by Thomas S. Allen, an early Tin Pan Alley composer.

I had long thought that the Low Bridge, Everybody Down song about the Erie Canal was of indigenous origin, written by a backwoods troubadour who adapted an old English or Welsh tune. This thinking was dispelled when I searched the Internet and found that the words and music were written in 1913 by Thomas S. Allen, an early Tin Pan Alley composer.

It was in 1944 or ‘45 when I first learned the Low Bridge song. We sang it in music appreciation class led by Miss O’Mara and Miss Secor at the Joseph H. Wade Junior High School in the Borough of the Bronx, New York. It was a great hit, as I recall, among the kids.

The words to the first stanza of the Erie Canal song are

I’ve got an old mule and her name is Sal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She’s a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

We’ve hauled some barges in our day

Filled with lumber, coal, and hay

And every inch of the way we know

From Albany to Buffalo

By the late 19th century, with the development of compact and reliable steam engines, mules which pulled canal boats were replaced by self-propelled canal boats and boats that were pulled by tugs.

Sal was made obsolete, and was put out to pasture, I hope. Since Sal was no longer needed, the towpath was also made obsolete, and so ended a romantic time when viewed from afar.

When the music appreciation class got to the chorus, we girls and boys belted out, as I recall

Low bridge, ev’rybody down,

Low bridge, we must be getting near a town

You can always tell your neighbor, You can always tell your pal

If he’s ever navigated on the Erie Canal

You can listen to a 1913 recording of the Erie Canal Song by Edward Meeker at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ep1hi6VBaWg.

If we think of the Erie Canal as the child of Middlesex Canal, then the child was overdosed from birth with growth hormone. The Erie Canal when first built was 363 miles long and ran from where Albany meets the Hudson River to where Buffalo meets Lake Erie. Construction began in 1817 and was completed in 1825. It had 84 locks and 18 aqueducts, and was four feet deep and 40 feet wide. The canal was built by the State of New York. It cost about $7 million, and the tolls collected paid back its cost in about seven years.

The Middlesex Canal was 27¼ miles long with 20 locks and eight aqueducts, and was 3½ feet deep and 30 feet wide. It opened in 1803 after ten years of construction, at a cost of $540,000. The Massachusetts legislature granted the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal a charter of incorporation that allowed them to raise money from private investors, and granted them power of eminent domain. The Middlesex was a financial loss for its investors.

The Middlesex may have been small and a financial failure, but I took heart after I read what Christopher Roberts wrote on p.100 of his book, The Middlesex Canal:

“These years of struggle with methods [used in the construction of the Middlesex canal] were a gain to American engineering. To the Middlesex as the most extensive work of its kind in the United States, the canal commissioners of the state of New York turned, in 1817, for example; and to the agent of the corporation, for precept [a principle governing actions or procedures].” Roberts found this in Official Reports of the Canal Commissioners of the State of New York (1817). (The brackets are those of the author of this article.)

As many members of the Association know, we have our own song, Haulin’ Down to Boston on the Middlesex Canal with the words and music written by Dave Dettinger. Go to middlesexcanal.org and as you scroll down on the home page, look on the left side for our song, sung by our troubadour, Paul Wiggen.

Boston & Lowell Railroad opened in 1835

by Larz F. Neilson

Two hundred years ago, there were only a few houses where the city of Lowell now stands. While it was the water power of the Merrimack River that powered the mills of Lowell, it was the railroad that built the city. [See end note.]

That was the Boston & Lowell Railroad, now the oldest operating rail line in the United States. The line runs through Wilmington, roughly parallel to Main Street.

It was also parallel to the Middlesex Canal, and it was the railroad that put the canal out of business. The canal opened in 1802. Twenty years later, Locks & Canals Corp. turned its first water wheel on the Merrimack. Raw cotton was shipped to Lowell on canal boats, and finished cotton was shipped to Boston. But the canal would freeze in the winter, limiting the transport of goods. Road transport was very difficult, often disrupted by snow or mud.

The concept of railroads came from England. The first railroad in the U.S. was built to move granite in Quincy in 1826, powered by horses. The same year, a line was built in Pennsylvania for hauling coal.

Lowell manufacturers sought to build a rail line in the late 1820s, but the Massachusetts legislature was slow to approve the idea. The railroad received a charter on June 5, 1830 giving it exclusive rights to provide rail service between Boston and Lowell.

The line was built on a carefully laid out 26 mile route through Charlestown, Cambridge, Medford, Winchester, Woburn, Wilmington, Tewksbury, Billerica to Lowell. No grade was greater than 10 feet per mile. Bridges were constructed to carry wagon traffic over the railroad.

The cost of construction was $1,600,000.

The railroad was built on a bed of granite at least four feet deep. In swamps such as in Wilmington, the stone base was much deeper. The ties were granite blocks, which turned out to give a very rough ride. They were eventually replaced with wooden ties.

Some of the work on the Boston & Lowell line was done by Asa Sheldon of Wilmington. He built the section north of the Wilmington depot through the Eldad Carter farm. James F. Baldwin, who engineered the project, told him it was the best piece of road between Boston and Lowell. The train engineer said that if he were blindfolded, he could tell when he struck that piece of way. Sheldon wrote about it in a book he called Wilmington Farmer. He was more like a contractor than a farmer. The book has been republished under the title Yankee Drover.

The first train on the Boston & Lowell ran on June 24, 1835, making the trip in one hour, 15 minutes. The fare was $1 for the trip. The locomotive was built in England in 1832 by Robert Stephenson. It was named Stephenson, but was commonly known as “John Bull.” It was first sent to Lowell on a canal barge.

Other early locomotives on the B&L were built at the Lowell Machine Shops. One was named Patrick, in honor of Patrick Jackson, president of the B&L. Others were Lowell, Boston, Merrimack, Concord and Nashua. They were all wood-burning steam engines. The early locomotives had no cabs, and the engineers had to stand in the open.

Even before the first train ran, another railroad had been granted a charter. The Wilmington & Andover Railroad connected to the B&L at Wilmington, running its trains over the B&L tracks to reach Boston. Sheldon hauled the iron for eight miles of the W&A. Eventually, that railroad was renamed the Boston & Maine, taking over the B&L. The Wilmington depot of the W&A is still standing, having been moved to Church Street by Mrs. Dr. France Hiller in the 1890s. In 1851, locomotive races were held on a nine mile stretch from Wilmington to Lowell. There were six engines entered, all using a particular kind of wood, drawing a load of 70 tons and maintaining the same steam pressure. The “Addison Gilmore” of the Boston & Albany RR turned in the best time, 11 minutes, 29 seconds. The “Nathan Hale” from the Boston & Worcester 12 minutes, 56 seconds. “Addison Gilmore of the Passumpsic RR 13 minutes, 26 seconds. The “Union” of the Fitchburg RR, 14 minutes. The “Neponsett” of the Boston & Providence RR 14 minutes, 35 seconds. And the “Essex” of the Boston and Lowell, 14 minutes, 48 seconds.

[Note. Lowell was chartered as a town in 1826, population 2,500. In the 1830 census, Chelmsford had a population of 1,387, a decline of 148 from 1820 due to Lowell’ separation. In the 1830 census, Lowell 6,474. The center of Lowell before the railroad in 1835 was the intersection of Central and Market Streets where the City Landing for the canal boats was. Narrowly true that the railroad built the city, chartered in 1836, as it grew to 20,796 in 1840, three times the size of Worcester. But when waterpower was replaced by steam boilers and with cheap water transportation available for coal and cotton, not an expensive railroad, Fall River and New Bedford surpassed Lowell by 1900. See Cotton Was King by Arthur L. Eno, Jr., editor, 1976, p. 145. Note by J. Breen.]

Presentation about Tide Mills from Revere to Quincy. 2019

by Earl Taylor

Introduction

Tide mills and tide mill buildings have largely disappeared from the North American coast. The buildings were constructed for a utilitarian purpose without much concern for architectural style. The fact that they are not visually picturesque may be part of the reason for their loss.

Two known tide mills and their internal equipment survive -- one on Long Island and one in Virginia. Even with surviving buildings, the structure is not original. Mills suffered fires, flooding and other damage, and they were constantly being rebuilt.

In urban areas, tide mill ponds have been filled in, and the sites of tide mills have been covered over for new development for industrial parks, highways and playgrounds. We know there must be remains of former mills buried underneath these developments, remains that can be found only through archaeological investigation. We are able to see artifacts only in less developed landscapes, where the physical evidence is not yet covered over. In our urban areas it is nevertheless possible to occasionally find evidence of what came before. Sometimes it is a road that forces us to go in a certain direction although it would seem natural to turn another way. Sometimes an old tide mill pond encompasses a whole newer neighborhood or a site has been incorporated into a “new” green space.

Definition of a Tide Mill

“A tide mill is a water mill that derives its power, at least in part, from the rise and fall of the tides. What counts is that the water behind a mill dam can be put to work only after the water level outside of the dam has dropped sufficiently during the ebb tide.” 1

One of the unusual features of a tide mill had to do with its hours of operation. The fact that the miller must wait for the tide to ebb before operating the mill is the determining factor in the definition of a tide mill. Although it is a stretch of the imagination, one can imagine a mill within the tidal zone that has a mill pond fed solely from a fresh water stream, but even if there is no salt water in the pond, the mill cannot operate as long as the level of the tide is high enough to impede the operation of the water wheel.

Because the time of high tide changes each day by about an hour, workers at these mills had to keep an eye on the height of the water rather than focusing on the clock. The schedule was predictable, but annoying, as high tide occurs at different times of the day, a day being 23 hours and 50 minutes in length, creating some unusual hours of work. The result was that for each 12 hour cycle, the mill was in operation only 6 to 7 hours. The advantage of tide mills that unlike river mills, their mill ponds are unlikely to freeze fully in the winter and not to go dry in the hot summer months.

Tide Mills from Revere to Quincy

Our armchair tour has two tide mill buildings as bookends, one in Revere and one in Quincy. They no longer have their interior equipment, yet we are lucky to have the actual mill buildings within easy distance from the central city.

We will explore the waterways that are adjacent to Boston Harbor. The coastline from North Chelsea (now Revere) in the north to Quincy in the South has many inlets that could have been suitable for tide mills. We will take a look at some of the known tide mill sites.

Revere/Chelsea

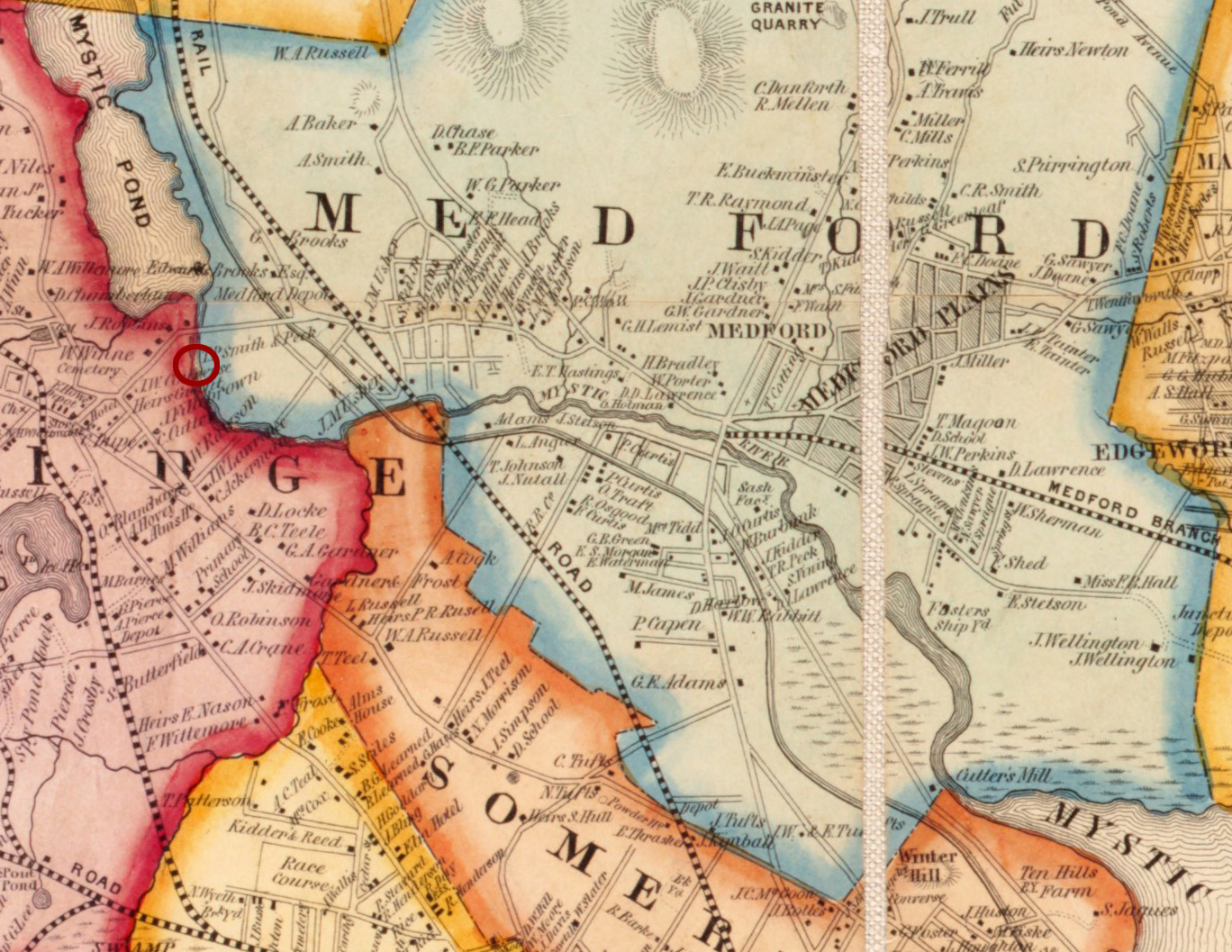

Detail from Map of Boston area and harbor - Map of the City and Vicinity of Boston, Massachusetts. (J. B. Shields, 1853)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

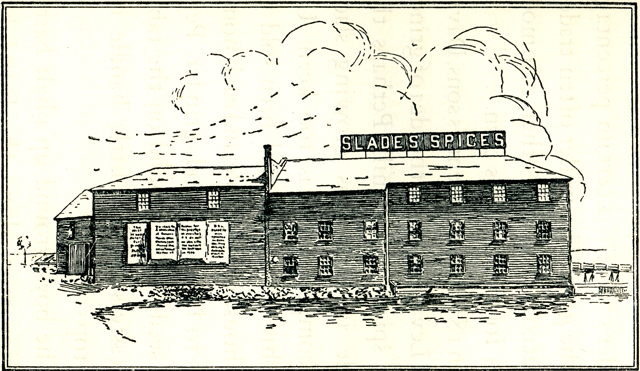

Slade Mill black & white illustration from The Spice Mill on the Marsh. |

Revere was part of Chelsea until March 24, 1871 and had been called North Chelsea, while all of Chelsea was also called Rumney Marsh. In 1721, the people of Rumney Marsh petitioned the selectmen for the right to build a tide mill. The first mill, built 13 years later in 1734 by Thomas Pratt, was originally called “The Mill” but later came to be known as Slade’s Mill.2 From the inventory of the estate of Samuel Watts, Feb. 28, 1771, we know there were two mills at this location.3 In 1816, after what appears to have been a disastrous fire, the town petitioned the General Court for permission to rebuild the dam across the tidewater creek on the site of the old mill. The old owners were bought out for two hundred pounds sterling and a new tide mill was erected on the spot, which was in continuous operation from then until the 1920s.

Cover of Smith, Thomas P. The Spice Mill on the Marsh - "The Colonial Slade Mill – Foundation of a Spice Empire" on http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/ the-colonial-slade-mill-foundation-of-a-spice-empire/ |

|

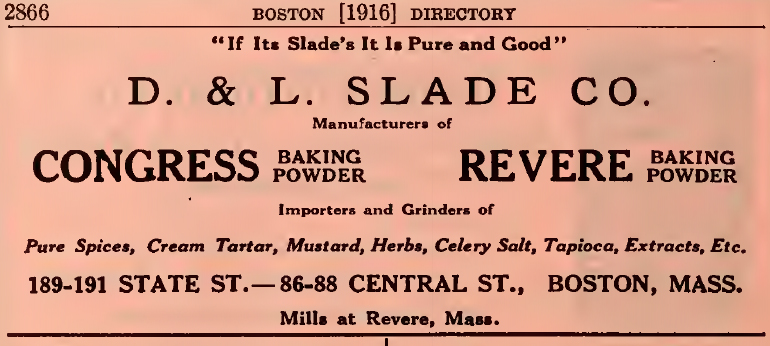

| Slade display advertisement - Boston Directory for 1916 |

In 1827 a share in the mill property passed into the hands of Henry Slade. Under his management the mill began to grind snuff as well as corn. [The farmer] brought grain to be ground, paying for the service a miller’s “dole”--a certain percentage of the grist.4

In 1837 two of Henry’s sons, David and Levi, conceived the idea of grinding spice in the mill. Up to this time spice had been sold to the housewife whole, and each home had to have its hand grinder. The two boys renovated the mill and soon spices such as cinnamon, pepper, and ginger were imported from places such as Sumatra, Ceylon(Sri Lanka), and the East Indies to Slade’s Mill to be ground into products that sold in packages of convenient sizes.5

Originally planned to be a grist mill, the charter stated that the mill must at all times hold itself in readiness to grind corn for any Chelsea as long as the corn is raised in the town. Technically this condition followed the mill throughout its history, but as time progressed, there were fewer Chelsea residents requiring the service of the mill.

The business name was changed to D. & L. Slade for David and Levi, and that is the name found in directories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Tidal power gave way to electricity. “Electricity as a motive power has increased the efficiency at the expense of the romance because the power from tides alone is intermittent, averaging only about six to seven hours in every twelve.” 6

In 1918 Slade would make the investment that keeps its legacy alive. It bought out Bell’s Seasoning Company. In 1867 William Bell had begun selling his blend of poultry seasoning through his market in Boston. Bell expanded his product range, and at his death, Slade purchased the brand, keeping the name and the formula bringing the Bell’s products into the Slade line.7

There is a reference to another tide mill in Revere (North Chelsea). John Cutter of Cutter’s Mill in Winchester and the mill in Medford built a grist mill in 1817 in North Chelsea run by tide water which was occupied by his sons until the year 1830 when they sold.8

Slade Mill photograph of the building converted to residential use, photograph courtesy of John Goff |

Winthrop

Detail from Map of Boston area and harbor - Map of the City and Vicinity of Boston, Massachusetts. (J. B. Shields, 1853)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

Winthrop became part of Boston in 1632. In 1739 what is now Chelsea, Revere and Winthrop withdrew from Boston and formed the town of Chelsea. There is a reference to another tide mill in the documents of the Massachusetts Legislature: An Act for improving and working a newly invented Floating Tide Mill between Chelsea and Deer Island 9 at Shirley Gut. The Gut was the channel between Deer Island and what is now Winthrop before the causeway road was built. The boat mill in the illustration is a Chinese boat mill from the 1930s and is presented to show what a floating tide mill might look like.

Chinese Floating Boat Mill from the internet

East Boston

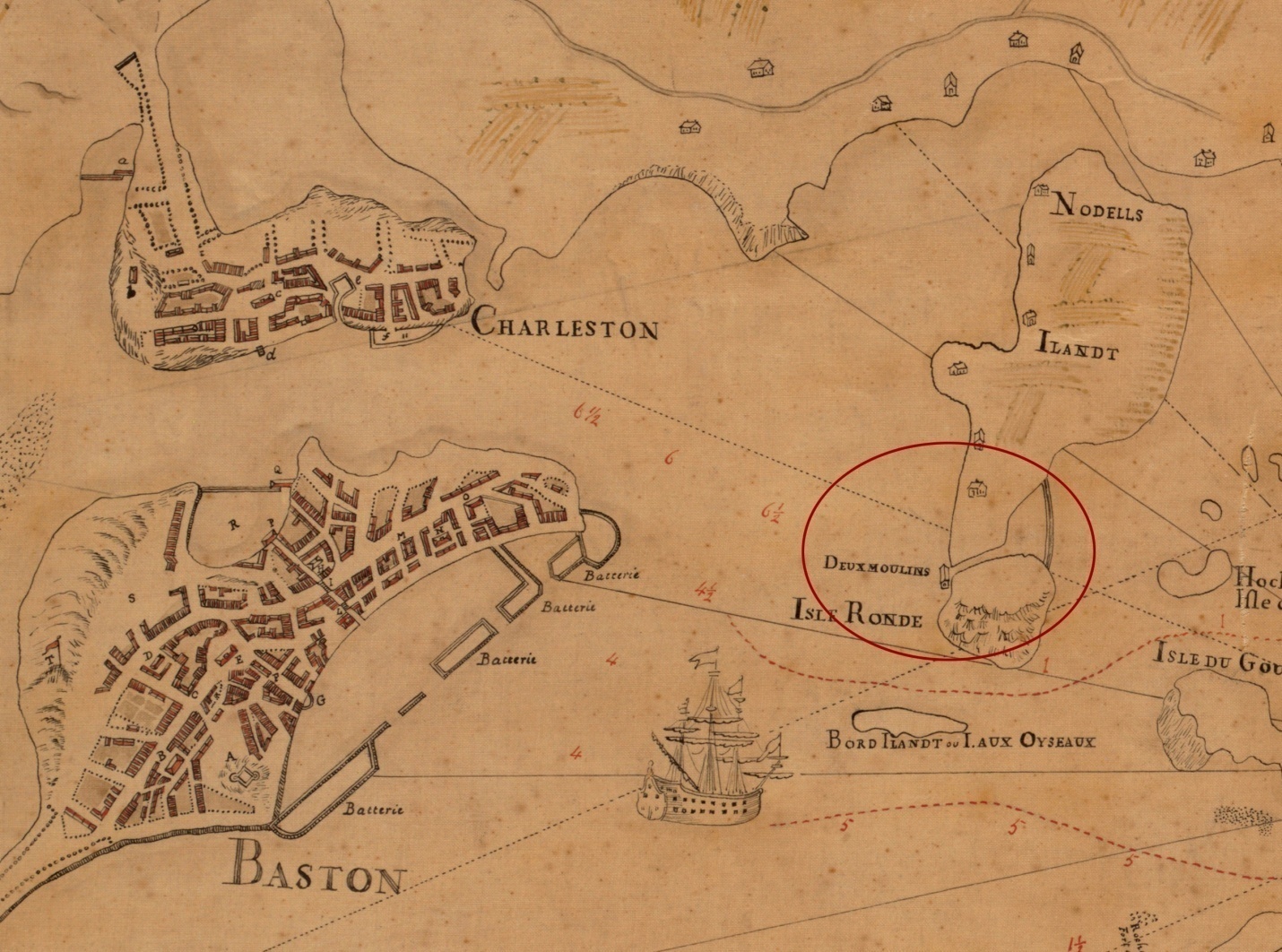

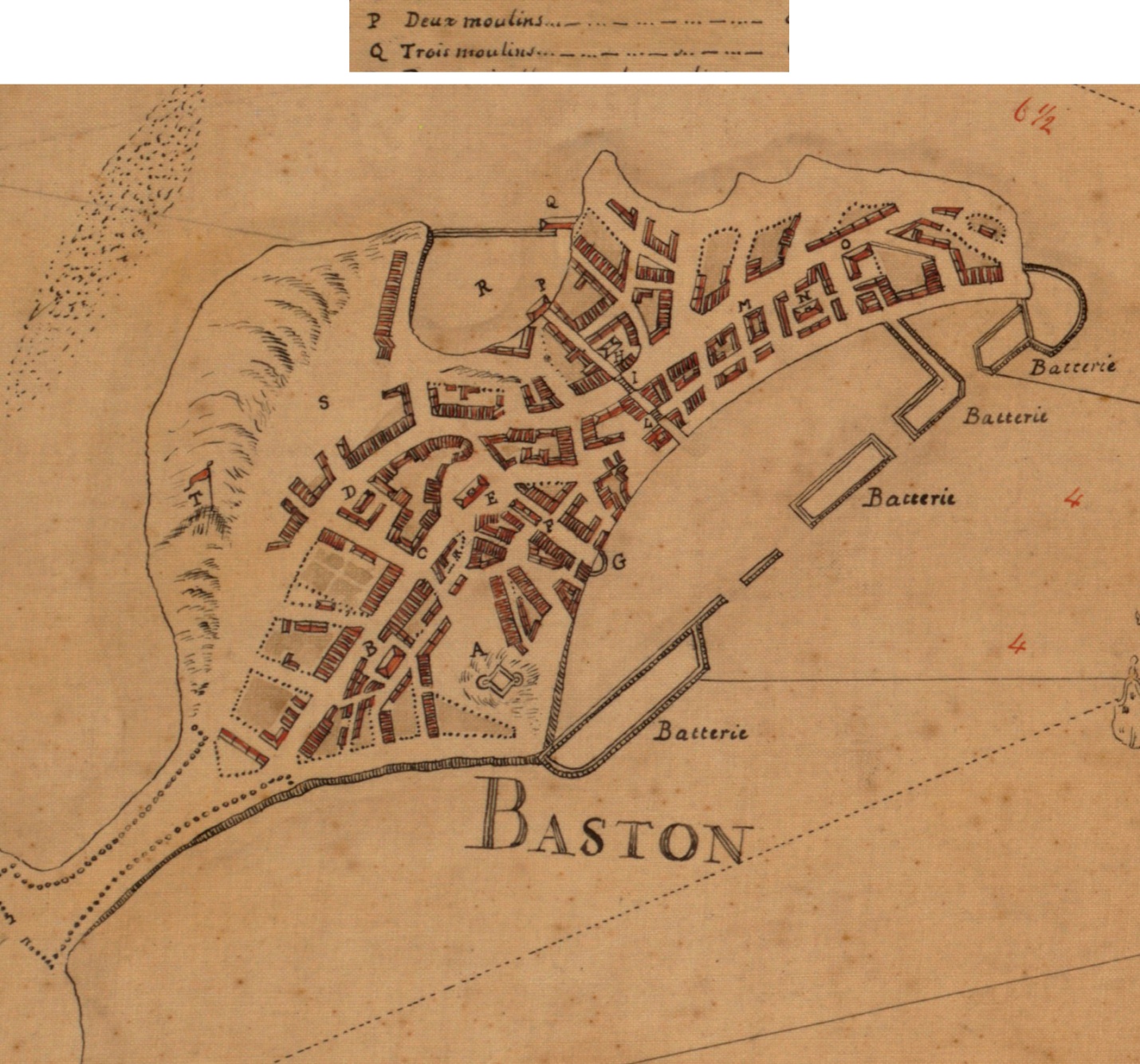

Franquelin, Jean Baptiste Louis. Carte de la Ville, Baye, et Environs de Baston. (1879) "Traced from the original in the Dépôt des Cartes de la Marine at Paris & presented to the Boston Public Library by Alfred Greenough, Architect, June 1879." Original version : 1693. - from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

“Noddles Island had a tide mill of unknown date of origin. ... In 1698 Medford citizens sometimes had to go as far as Noddles Island to have their corn ground. The 1693 map shows the legend of “Deux moulins,” or two mills. ...” 10 There is mention that prior to 1698 Medford families needed to travel to Noddle’s Island to have their grain ground.11

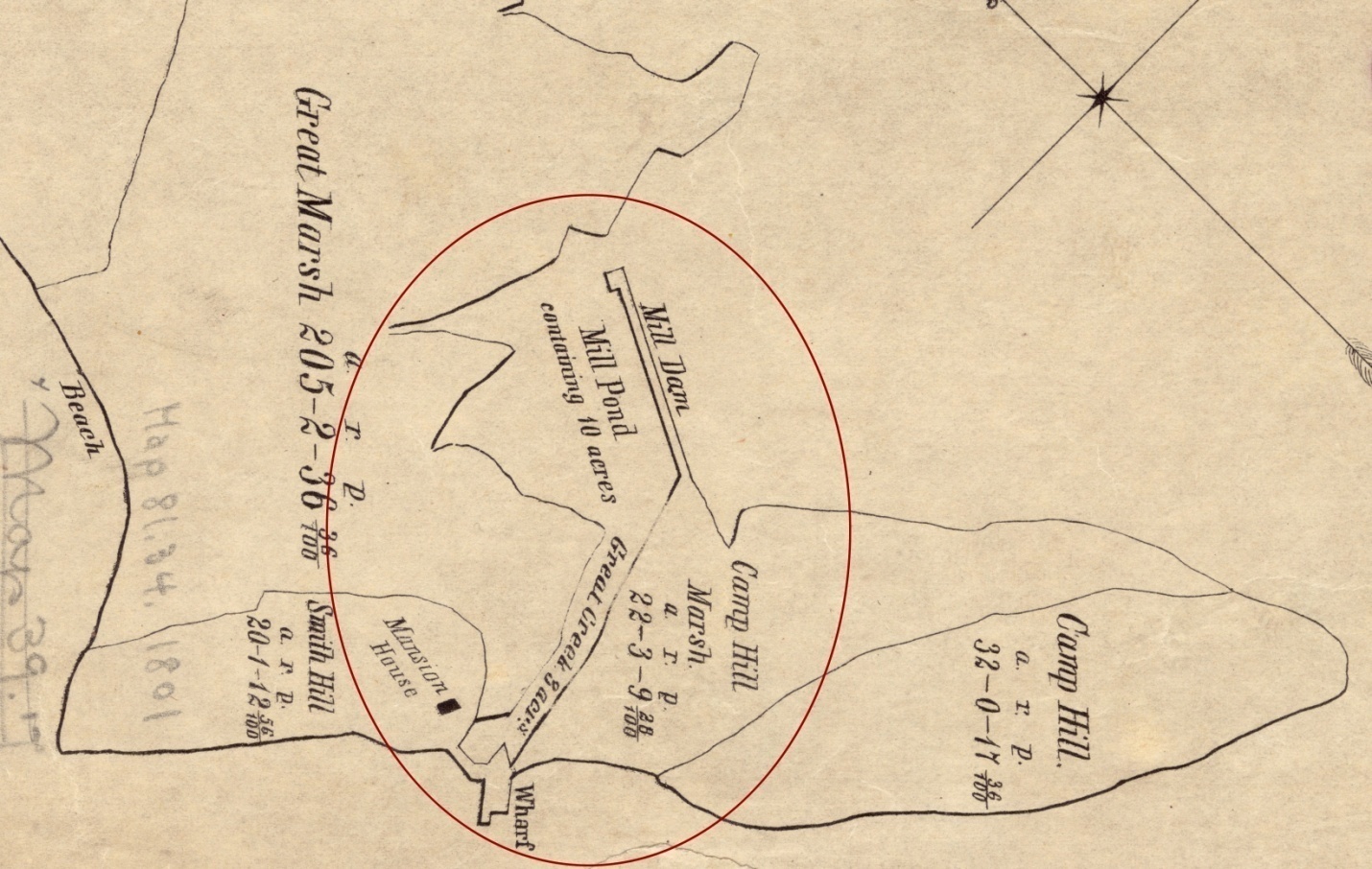

Taylor, William. A Plan of a Survey of Noddles Island. (Boston: J.H. Bradford's Lith., 1801)

The 1801 plan shows a mill dam enclosing a pond of 13 acres. So really all we know is that there was an important tide mill on Noddles Island between 1680 and 1720 that was used by Medford farmers until a grist mill was constructed in that town.

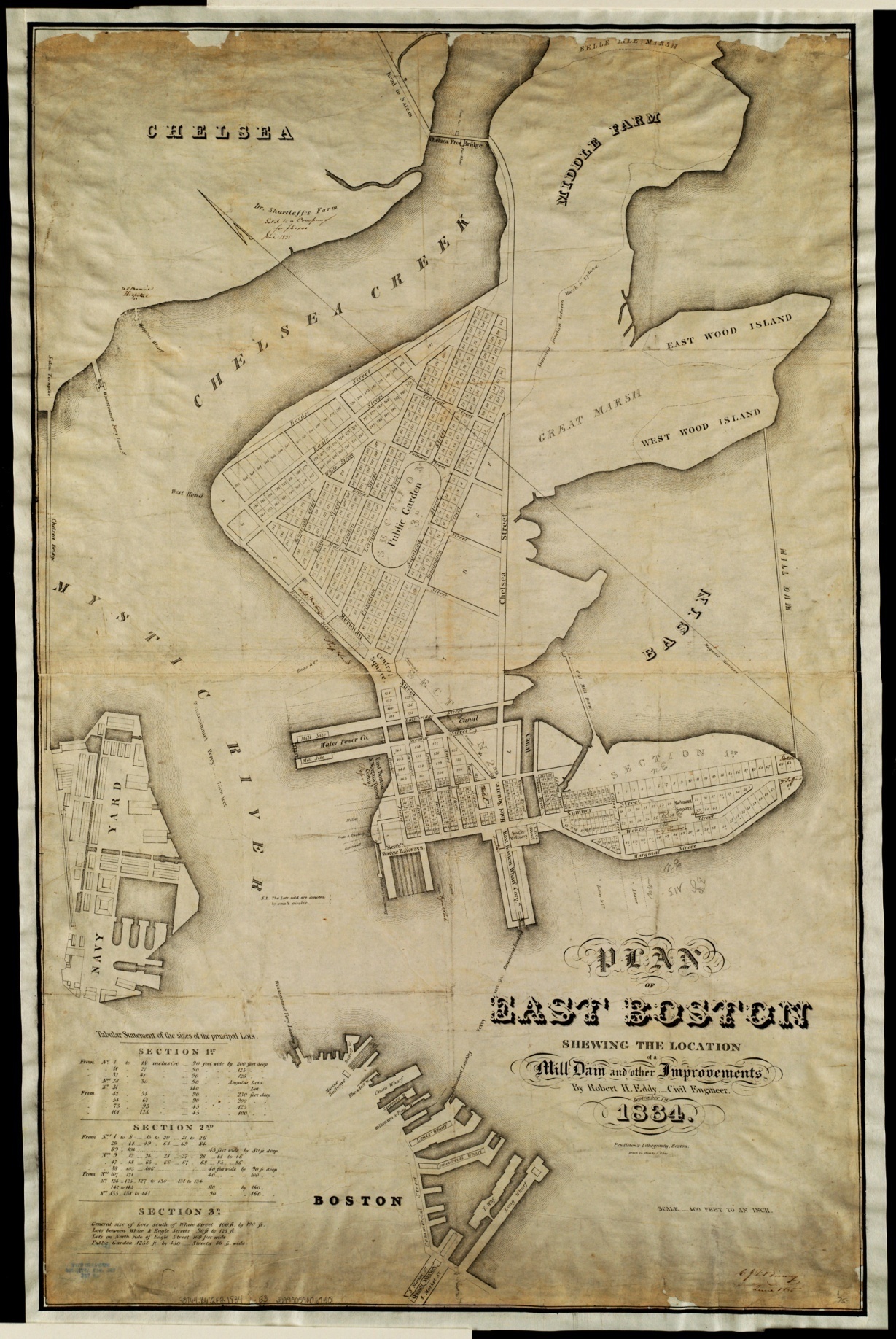

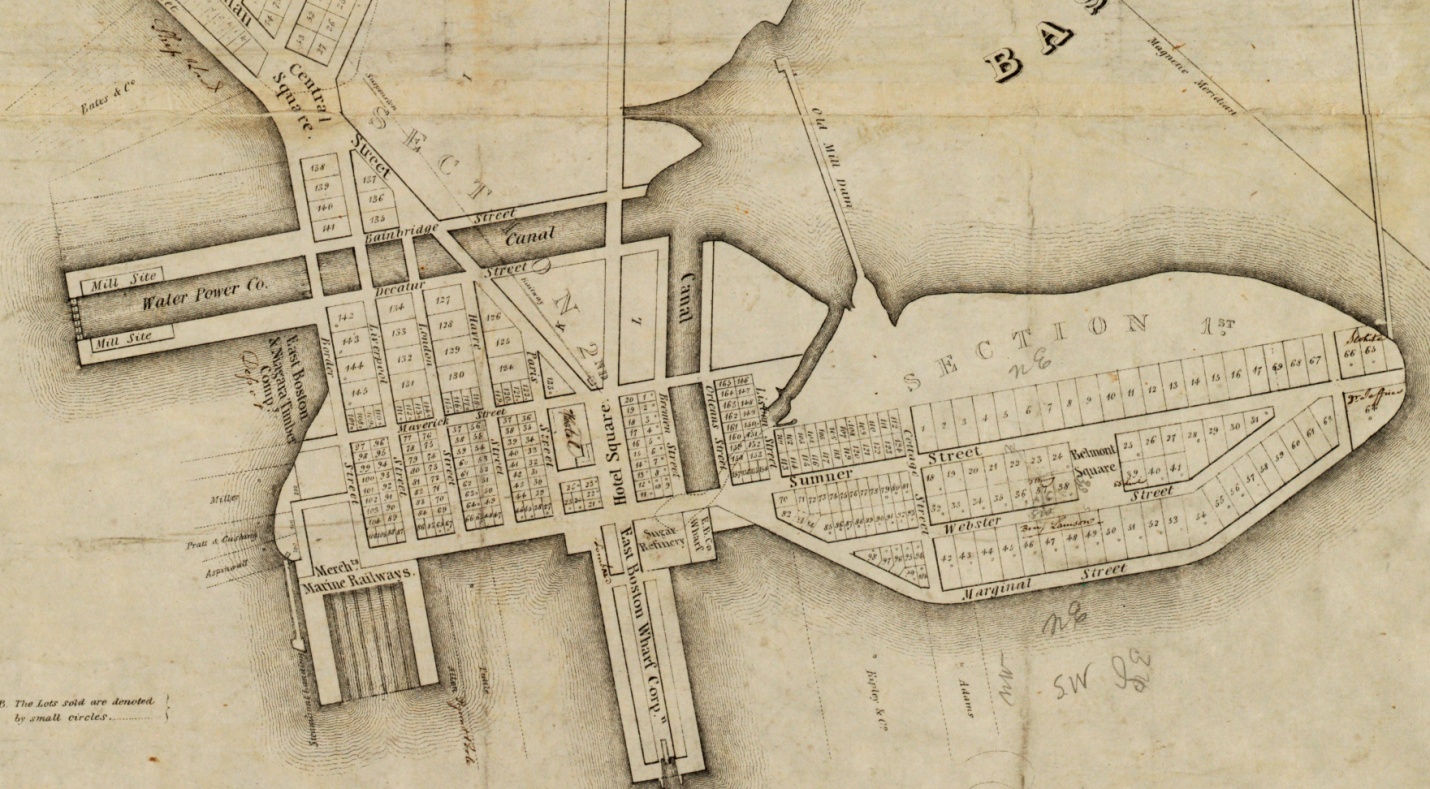

Eddy, R. H. Plan of East Boston Shewing the Location of the Mill Dam and Other Improvements. (Boston: Pendleton's Lithography, 1834).

Detail from Eddy, R. H. Plan of East Boston Shewing the Location of the Mill Dam and Other Improvements. (Boston: Pendleton's Lithography, 1834).

A plan for tide mills was mentioned in the 1830s, although it appears the project never came to anything. The dam for the early tide mill can be seen in the center, and the proposed dam far to the right. In 1836 an application was planned to incorporate The East-Boston Water Power Company with a purpose of “inclosing, by a granite dam, from West Wood Island to the extremity of Section No. 1 as seen on the plan, a space of about 180 acres of water, and thus to create water power for general and manufacturing purposes ... the power thus to be created is reckoned by the Engineer as equal to forty mill powers.” 12 Looking at the map, we can see the old mill dam with an opening at its north end and the new mill dam of 3700 feet, enclosing the flats called the Basin. When the tide was full, the water could be used for a tide mill-pond, with canals. The canal leading westward was 180 feet wide and extended 1,000 feet with corresponding mill sites on each side.

Medford

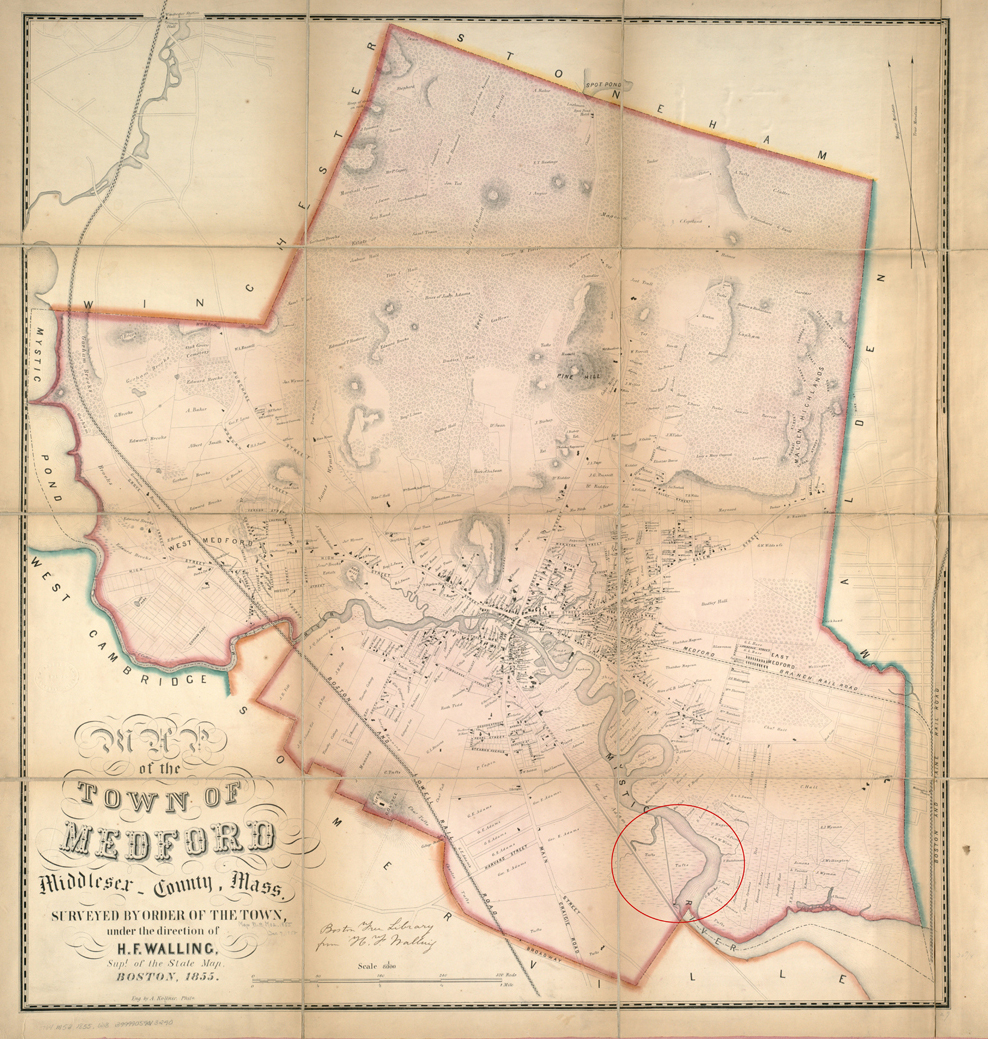

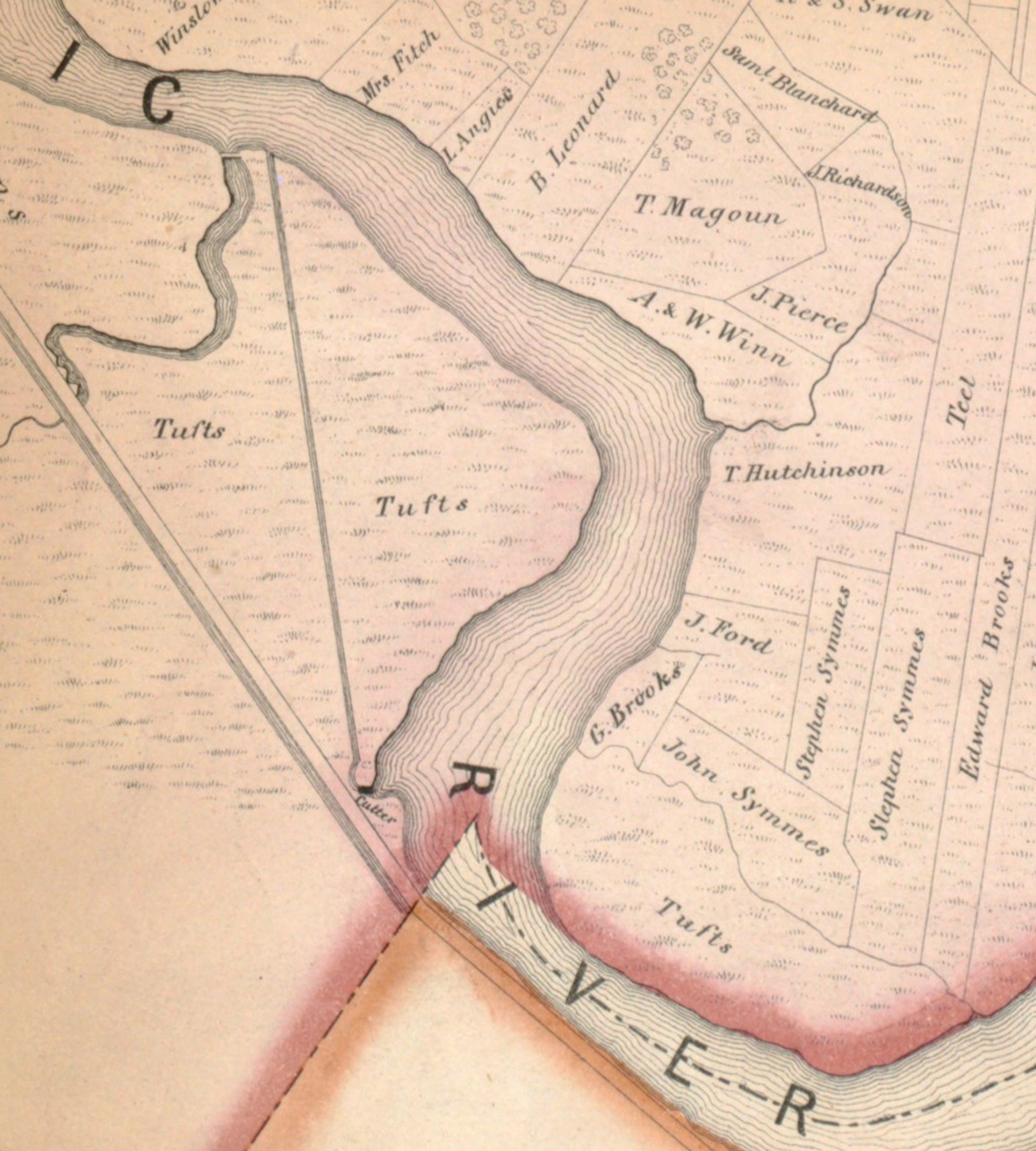

Map of Medford - Walling, Henry Francis. Map of the Town of Medford, Middlesex County, Mass. (1855)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

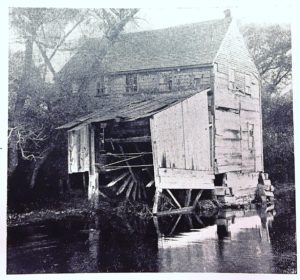

Cutter’s Mill was located on a marsh formerly belonging to Tufts.

Detail Map of Medford - Walling, Henry Francis. Map of the Town of Medford, Middlesex County, Mass. (1855)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

The old Tufts Mill/Cutter Mill stood just within the border of Medford. The marsh on the upper side of the mill collected water both from the incoming tide and from fresh water flowing downstream. The canal together with the marsh constituted the reservoir. A “dike” extending from the mill diagonally across the “meadow” to the river impounded water that furnished power as the tide receded.13 Four successive mills stood on the site.14

Gershom Cutter Jr. came from a family of millers. His great uncle Zachariah or John or both operated the old tide mill in Medford near the Town Square. Gershom sold his family’s old mill business at Town Square and purchased this mill, the Tufts Mill on the Medford Turnpike (now Mystic Avenue) in 1845 and rebuilt it. He was mainly engaged in the sawing of mahogany. The mill was lost to fire in 1872.15

Detail Map of Medford - Walling, Henry Francis. Map of the Town of Medford, Middlesex County, Mass. (1855)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

“In 1746 the tide mill near Sandy Bank was built, the first of its kind in that part of the town. Its origin arose in articles of agreement between a number of citizens, owners of the land, and a number of other citizens who were the undertakers of the enterprise. These articles were dated Feb. 20, 1746. Certain procedure was necessary to complete the undertaking, such as giving lands, and opening a straight road from the market to the mill site, and building a stone bridge over Gravelly creek for the mill’s accommodation, the building of a dam, etc. The mill was to be ready for use before the last day of September, 1746. It was successfully completed and answered well its purpose.” 16

It was successfully completed and answered well its purpose. Timothy Waite, Jr., acquired possession at an early period in its history. Seth Blodget bought it of him on March 9, 1761. Matthew Bridge followed Blodget on Oct. 18, 1780. Mr. Bridge disposed of it to the Bishops —John, Senior, and John, Junior—in 1783 and 1784. John Cutter occupied the mill by 1788.17 John Bishop, probably the junior, sold the whole to Gershom Cutter, who was followed in ownership by Samuel Cutter, George T. Goodwin, and Joseph Manning.18

Detail Map of Medford - Walling, Henry Francis. Map of the Town of Medford, Middlesex County, Mass. (1855)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

The earliest grist mill was soon after 1698 in West Medford near Harvard & Fairfield Streets. The people of the town petitioned the Governor and General Court to authorize setting up a mill on the Mystic River. The petition was approved in December 1698.19

In July, 1911, an old oak frame of a building was discovered in West Medford, near Harvard and Fairfield Streets, which has been suggested was the frame of the mill building.

Also notice the location of this mill in relation to High Street in Medford a little way north. We will see High Street in the illustrations when we look at Arlington.

Arlington

Map of Boston area and harbor - Map of the City and Vicinity of Boston, Massachusetts. (J. B. Shields, 1853)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library. West Cambridge later became Arlington.

The Mystic River is very different today from what it was in the 18th century and even the first half of the 20th. We know from a study of the Mystic River that it was tidal all the way to the southern edge of Mystic Lake.20 There are mentions of various mills on the Mystic River. The site of the Woods Mill was a “short distance below the Wear Bridge, but who built it, and how long it stood, we have not been able to discover. The place is yet occupied.” 21 The old tide mill site was visible from the bridge at High Street.22 The study of the river in 1861 stated, “We find the ordinary limit of the tidal wave to be at or near wood’s Mill, and beyond this point the river ceases to be of value at present as a tidal basin of the harbor.” 23

Deed plans from Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge.

Edited and with Commentary by Richard A. Duffy (Arlington, 1999). Original novel published 1882.

The following is from Richard Duffy’s essay in the re-issue of The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J.R. Trowbridge. Benjamin Woods was the owner of the mill in the mid 19th century. In the record for the birth of his second child, Benjamin’s occupation is listed as a wood turner. The 1865 census of West Cambridge gives his occupation as turning and sawing. Woods placed two classified advertisements in the Arlington Directory of 1867, identifying his wares as Parlor Brackets and Children’s Carriages, i.e., doll carriages. After the Upper Mystic Lake reservoir was complete in 1865, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts ordered the removal of the tidal gates. In the spring of 1867 Woods rebuilt his own dam more simply by driving pilings and inserting flash boards. After complaints from boaters and a lengthy battle in court, the decision came down for the removal of his dam in 1872. He probably converted to steam to continue his business. He continued to make carriages into the 1880s. 24

The mill was described: The mill was a small two-story building ... The river-bank was there quite steep, and entrance was had into the second story from the land adjoining by a connecting bridge. The building projected somewhat over the river, was supported by stones and timber, and the water-wheel was enclosed by the first story. It was of the undershot variety, its paddles dipping into the current, which, as the tide ebbed, ran very swiftly, and was accelerated by the fall of less than two feet caused by the dam. ... The proprietor was B. F. Wood, who lived in a large white house on the level plain nearby, who did wood-turning, jig-sawing and like work, also making baby carriages and curtain fixtures in his mill.25

Wood's mill from Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge.

Edited and with Commentary by Richard A. Duffy (Arlington, 1999). Original novel published 1882.

Wood's mill from Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge.

Edited and with Commentary by Richard A. Duffy (Arlington, 1999). Original novel published 1882.

Advertisement for Children's Carriages from Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill.

Charlestown

Plan of Charlestown 1848 - Barker, Ebenezer. Plan of the City of Charlestown. (Boston: J.J. Bufford's Lith., 1848)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

There was a tide-mill in Charlestown by 1645 and maybe earlier. In 1693 this mill pond had two mills. The dam enclosed a large mill pond of about 30 acres on the south side of Charlestown Neck.

Roger Sedgwick and William Stitson were part owners of this mill and undoubtedly built it. Their agreement stipulated that Sedgwick would receive 1/3 of the profit for the year. By law he could take only “one-sixteenth part of the corn he ground and was obliged to keep ready for use mill weights and scales. The owners of the mill were to allow two ditchfuls of corn every time the mill was dressed, eight gallons of lamp oil, for use of the mill; and provide a house for the miller to reside in, or pay thirty shillings per annum.” 26

The owner of the mill during the Revolution put in a claim for damages after the War, listing a mill-house with two grist mills, a fulling mill with three pairs of stocks, two stores, a barn, a dwelling house, gates to the mill pond, etc., for 800 pounds.27

“In 1803 the Middlesex Canal Corporation bought the entire Charlestown mill property and constructed a floating tow path along the northeastern side of the mill pond from the dam to the beginning of the canal property near the neck. Then in 1826 the company filled in the northeastern side of the pond so that the tow path could be on solid land ...” 28 An 1850 map still shows the mills, although it is unclear if the mill operated after the purchase by the Canal Corporation. The filling of the pond began in earnest after 1868.

The Tufts Mill pond was located on the Mystic River side of the Neck. The city acquired Tufts Mill Pond in 1891 along with an abutting tannery and converted them into a park with filling completed in 1905. This was the Charlestown Playground until 1942 when it was renamed the John J. Ryan, Jr., Playground.29

Boston

As I have mentioned we don’t have visible archaeological remains in the Boston area to remind us of our past, but we can view old tide mill sites as we have been doing, and we certainly follow unwittingly the patterns established hundreds of years ago by the siting and building of tide mills. In the North End and West End we have Causeway Street and the Bulfinch Triangle, and in the Back Bay we have Beacon Street and our knowledge that the buildings of the Back Bay were built on made land.

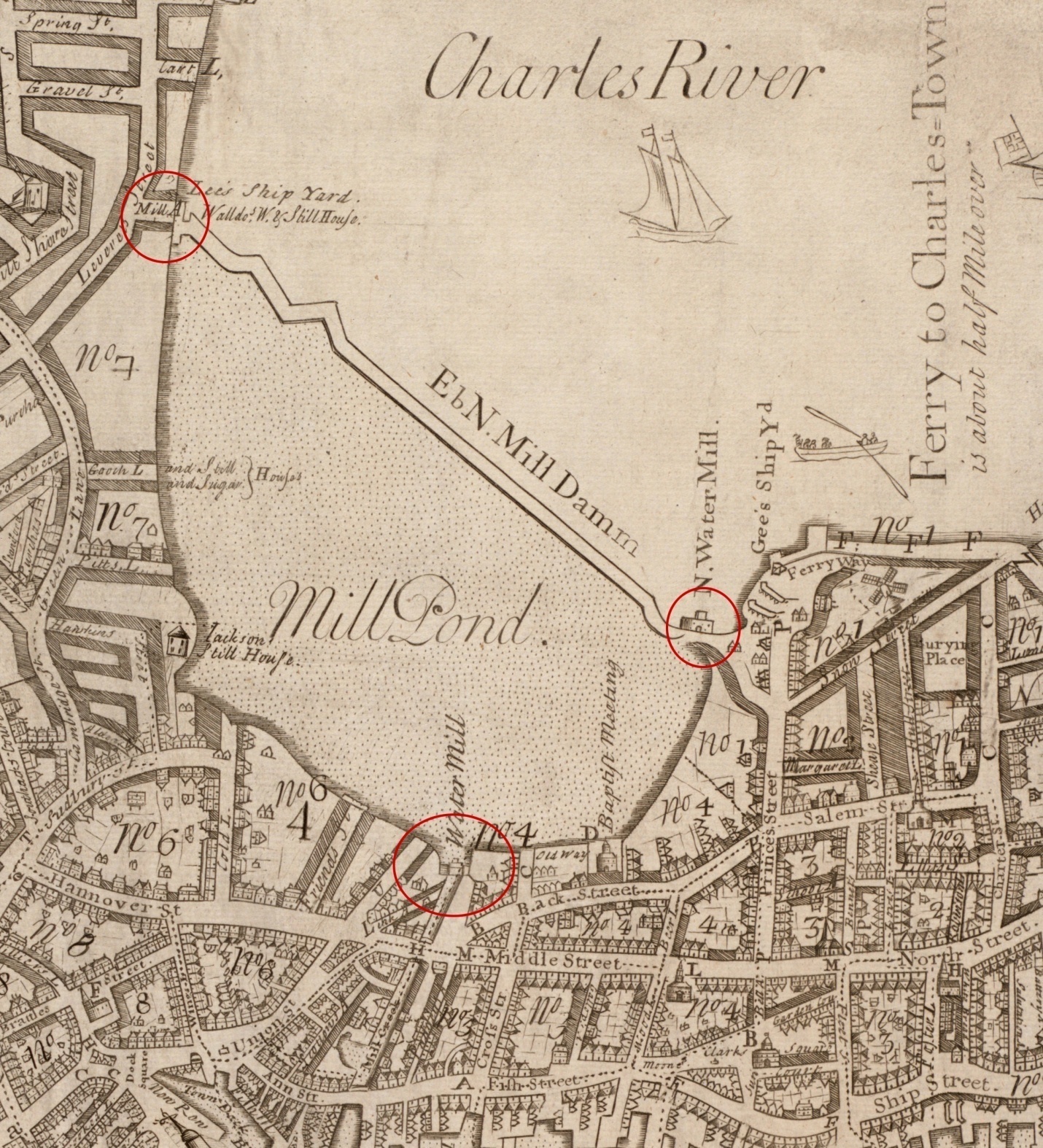

Mill Pond

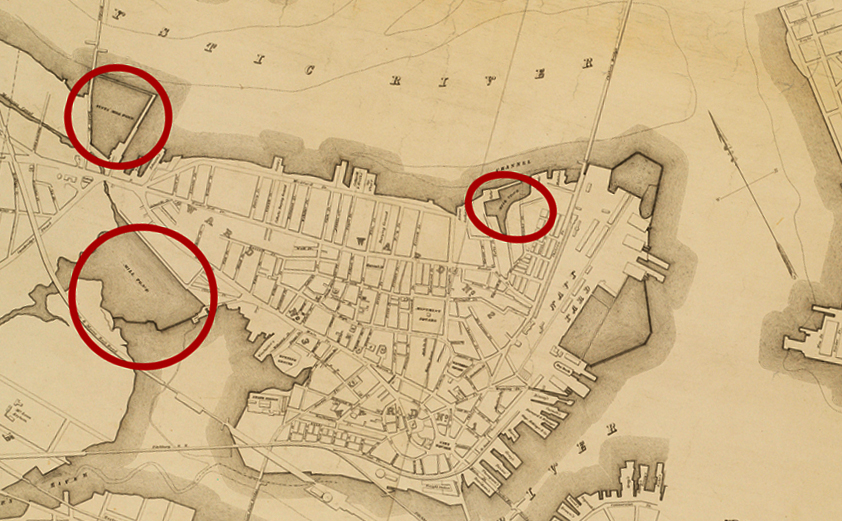

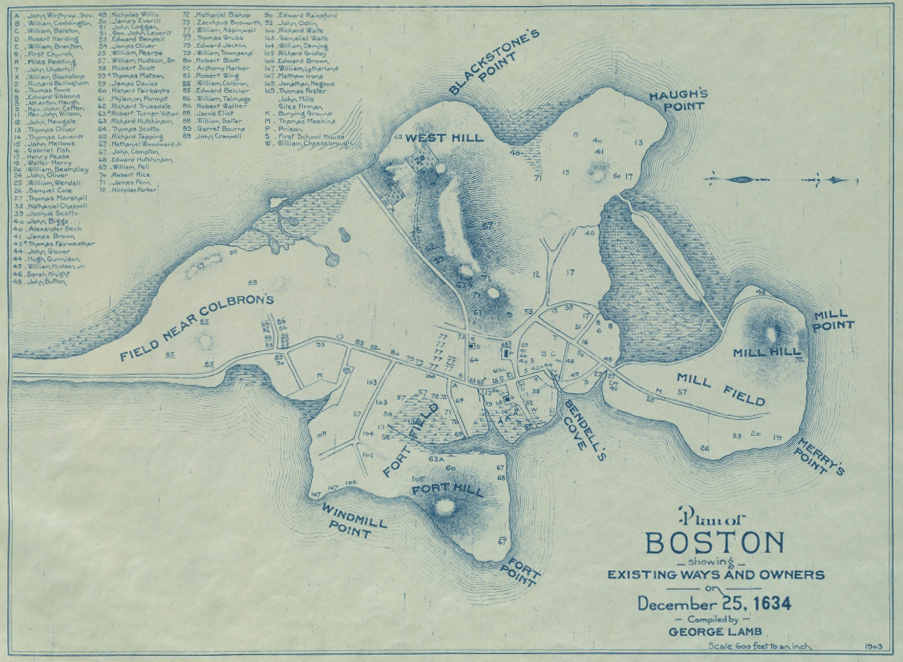

Plan of Boston 1634 - Lamb, George. Plan of Boston Showing Existing Ways and Owners on December 25, 1634. (1903)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

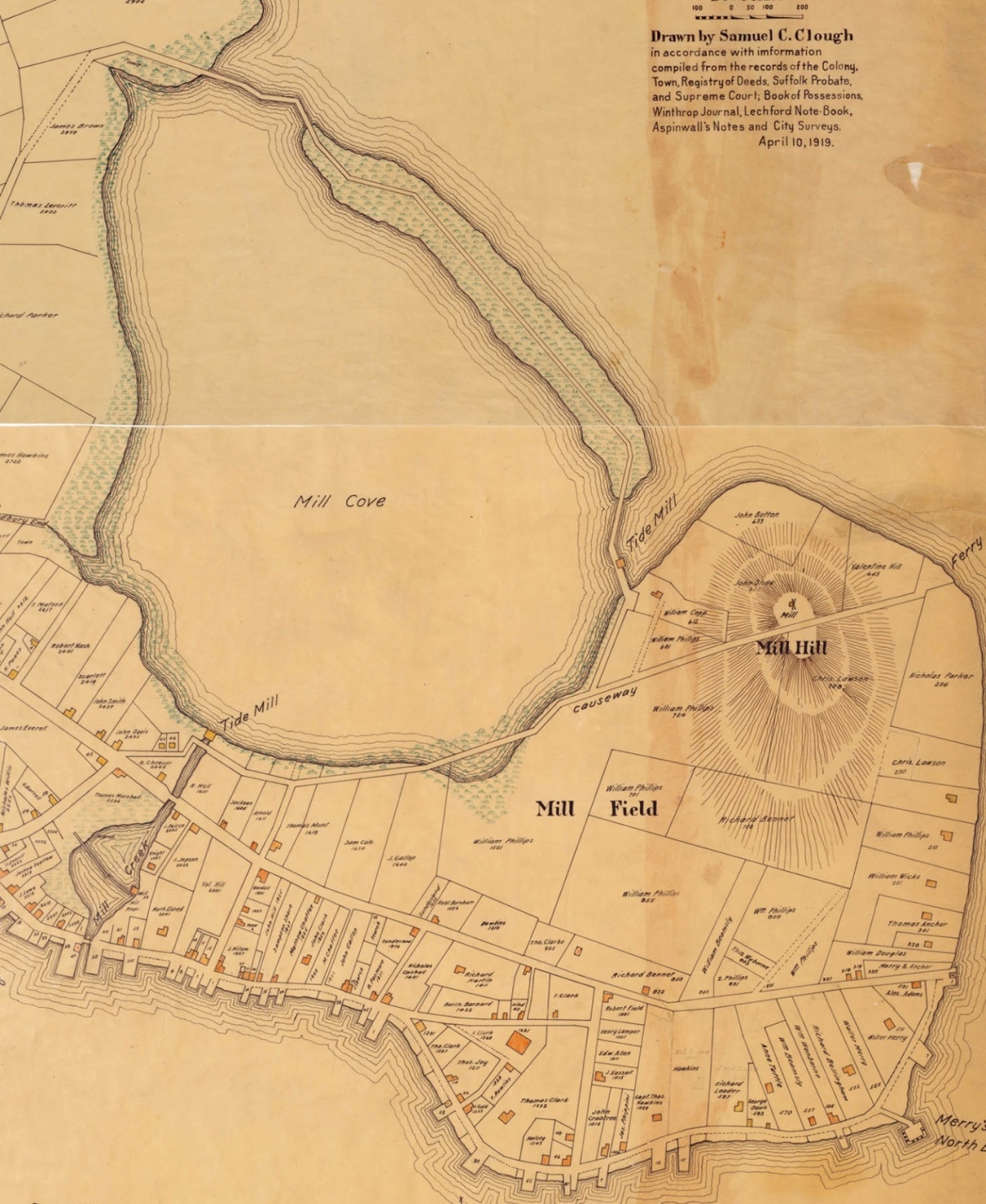

Boston 1648 - Clough, Chester. Map of the Town of Boston 1648.

Drawn by Samuel C. Clough, in Accordance with Information Compiled from the Records of the Colony. (1919).

- from the Massachusetts Historical Society.

In the 17th century, the area between the West End and the North End was a marshy cove with a narrow barrier island between the marsh and Boston Harbor. In 1643, Boston granted a group of investors ownership of the cove and its surrounding marsh on the condition that within three years they erect and maintain one or more corn mills along the shore. They dammed the cove and enlarged a waterway to create a channel called Mill Creek to connect the new pond to Town Cove (adjacent to Long Wharf) and constructed floodgates at the north and south ends of the dam. The dam later became Causeway Street. The mills at the dam were called the North Mills and the mill at Mill Creek was called the South Mill, and they included a “grist mill, a saw mill, and in later years a chocolate mill.30

Boston 1693 - Franquelin, Jean Baptiste Louis. Carte de la Ville, Baye, et Environs de Baston. (1879)

"Traced from the original in the Dépôt des Cartes de la Marine at Paris & presented to the Boston Public Library by Alfred Greenough, Architect, June 1879."

Original version : 1693.- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

Locations P & Q in the map are shown in the legend to have had multiple mills.

Franquelin’s Map of 1693 shows there three mills at the north mill and two mills at the south mill.

Boston 1743 - Price, William and Bonner, John. A New Plan of ye Great Town of Boston n New England in America. (1743)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

In 1807 a town committee reported their conclusion that the pond should be filled for the health of the citizens and the enlargement of the town. Boston authorized filling of the Mill Pond, to be completed within 20 years. The Town would keep one-eighth of the land created.31

In 1928 North Station was built atop the dam area; its address is 126 Causeway St.

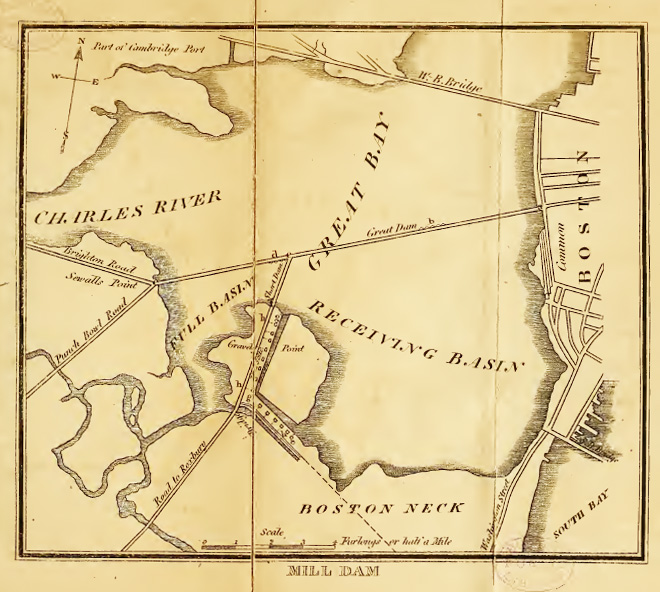

Back Bay

Hales, John G. A Survey of Boston and Its Vicinity. (Boston, 1821).

- from the Lebenthal Map & Education center, Boston Public Library.

“One of the greatest engineering accomplishments of early 19th century Boston was the construction, in the 1818 to 1821 period, of a causeway---the Boston & Roxbury Mill Dam---across the Back Bay.32

Uriah Cotting, merchant, real estate promoter and amateur engineer conceived a plan to harness the water power of the tidal Charles River for manufacturing. “The plan called for the building of two dams, one on either side of the Boston Neck. The first would extend from the foot of Beacon Hill to Sewall’s Point in Brookline (the present Kenmore Square), the other from Boston to South Boston. The resulting basins would be connected by raceways. At high tide, water would be allowed to flow into the Back Bay basin, and through the connecting raceways into the South Boston basin, before emptying into Boston Harbor at low tide.

Boston 1826 showing the Back Bay dam - Fuller, Stephen P. Plan of Boston Comprising a Part of Charlestown and Cambridge. (Boston: Annin & Smith, 1826)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

Cotting, who drafted the 24-page prospectus for the project, contended that the Mill Dam had the potential to provide power for 81 mills, including, 6 grist mills, 6 saw mills, 16 cotton mills, 8 woolen mills, 12 rolling and slitting mills, and also facilities for the manufacture of cannon, anchors, scythes, grindstones, paint, and other manufactured goods. While the Mill Dam would cost $250,000, a huge sum at that time, Cotting estimated that it had a potential to generate about $520,000 in income per year. Here, clearly, was an investment opportunity not to be missed!” 33

The plan as finally carried out eliminated the South Boston basin. The Mill Dam would be confined to the Back Bay, by constructing a cross dam to create a “full basin” and a “receiving basin.”

“First, a mile and a half long and 50 foot wide stone dam was built from the foot of Beacon Hill to Sewell’s Point (now Kenmore Square) in Brookline, enclosing 600 acres of the Back Bay. Then a cross-dam was constructed from Gravelly Point in Roxbury, subdividing the impounded area into two basins, a westerly full basin, of about 100 acres, and an easterly receiving basin of some 500 acres. At high tide the waters of the Charles would enter the westerly basin, pass through sluices into the easterly basin, turning turbines to generate power, before emptying back into the Charles at low tide.” 34 “The mill sites were along Gravelly Point, and each site had a mill race running from the Full Basin to the Empty Basin.” 35

It is perhaps fortunate for Cotting that he died in May of 1819, two years before the completion of the project, so he did not live to see the failure of the project. The failure, however, did improve the city by creating the opportunity for the Back Bay to become home to the handsome elite late Victorian residential district of our day, one of the architectural glories of Boston.36

Map of the Town of Roxbury Surveyed by John G. Hales (1834)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

Only a few mills were constructed. This map shows the City Mills near the intersection of the main dam and the cross dam.

The Mill Dam project failed to provide adequate power for the tide mills, and it also prevented sewage, which collected in the receiving basin from surrounding areas, from being carried off by the tide. By 1849, a city report stated that Back Bay had become “ a great cesspool …” In 1857, it was ordered to be filled. By 1861 one drug mill was the only mill operating in the Back Bay, and by 1882 the filling of Back Bay itself was completed.37

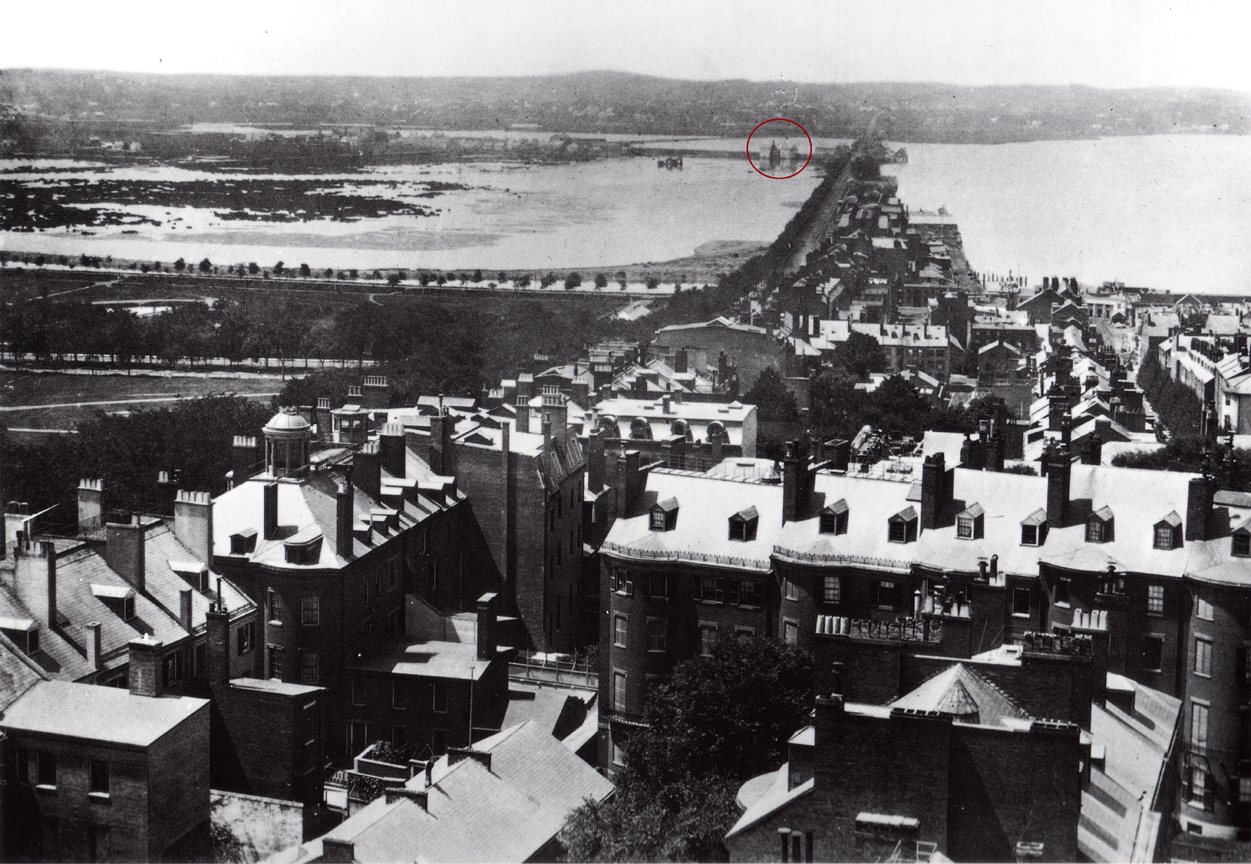

Bird's-eye View of Boston - Bachmann, John. Bird's Eye View of Boston. (New York: Williams & Stevens, 1850).

A small section of the receiving basin can be seen in this bird’s-eye view. Beacon Street and the Charles River are at the left. The eastern edge of the marshy receiving basin appears at the bottom of the view, closest to the viewer.

Photograph 1858 of dam and cross dam of the Back Bay - Seaholes. Gaining Ground.

RE: Back Bay dam – photo taken from State house in 1858

“In this view one can see the Mill Dam, now Beacon Street, stretching across Back Bay toward the Brookline hills in the distance. In the middle distance is the cross dam, on the line of what is now Hemenway Street, which met the main dam at a point now on Beacon street between Hereford Street and Massachusetts Avenue. The two white buildings are the flour mills that were powered by the dam.” 38

Roxbury

Hales, John Groves. Map of Boston and Its Vicinity. (Boston: John G. Hales, 1833)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

The old tide mill or mills of Roxbury pre-dated the damming of the Back Bay. They were located approximately where the Wentworth Institute of Technology is today. There are several mentions of the tide-mill near the landing place in Drake’s history of Roxbury. “The tide-mill at the landing was, in 1650, known as Baker’s Mill. ... In 1655, liberty was granted to John Pierpont and others to ‘sett down a Brest Mill or Vndershott in or near the place where the old mill stood...’” 39 There is a mention in the Heath papers from June 1775 of a tide mill in Roxbury.

Dorchester

Clap’s Mill, Mill Brook Creek, 17th century

Boston Map 1855 showing the South Bay - Colton, J. H. Map of Boston and Adjacent Cities. (New York: J. H. Colton, 1855)

- from the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

The earliest tide mill in Dorchester was the Clap Mill on Mill Brook Creek, a grist mill. It was described as standing nearly north-east of the estate owned and occupied in the beginning of the 19th century by Preserved Baker, not far from where the New York and New England Railroad reached the upland after crossing the waters of the Back Bay.40

Before Boston’s South Bay was filled in, the Bay was connected to the ocean by a passage between Boston and South Boston. The tidal marsh of the South Bay bordered Boston, Roxbury and Dorchester. Roger Clap was among the first to arrive in Dorchester. Mary and John, and some of his siblings and cousins arrived a few years later. They acquired land in the north part of the town fronting on the South Bay and extending to Boston Street, and they owned a tide mill known as Clap’s Mill. It stood on Mill Brook Creek, a creek that separated Roxbury from Dorchester, sometimes called Dorchester Brook or Roxbury Brook depending on one’s perspective. The Clapp Memorial, the family genealogy, says that the mill was built for them by a Mr. Bate. This was probably James Bate or Bates, a millwright who arrived in Dorchester in 1635 and remained there until his death in Dorchester in 1655.41 The Mill was located at the end of Willow Court.

Roger’s will mentions his meadow at the tide mill. Edward Clapp, brother to Roger, owned half of the mill. Following his death in January, 1664, his will passed one quarter each to his sons Nehemiah and Ezra, and the estate inventory describes it as a tidal mill. Half the mill was then valued at 50 pounds.42 Ezra moved to Milton where he had received other lands from his father and built a mill for grinding corn on the Milton side of the Neponset River. He may have sold his quarter of the South Bay mill back to the family since it is not mentioned in his will. Nehemiah stayed in Dorchester and died at age 38. In his will, probated in 1684, he left his quarter of the mill to his son Edward, who is characterized as probably rather a shiftless man who had a good estate left him, which he disposed of before he removed to Sudbury about 1722. Nicholas Clap, a cousin to Roger and Edward left a quarter of the mill in his estate.43

The mill was rebuilt by Jonathan Clap, a 3/4 owner and Humphrey Atherton in 1712. We assume that Humphrey owned the other ¼ of the mill. According to the articles of agreement for rebuilding it, Joseph Parsons, of Northampton, was to build a corn or grist mill at a place called Claps Mill where the former mill stood, for which he was to have 50 pounds, the mill to be finished by Sept. 12, 1712.44

In the second half of the 18th century, Ebenezer Clap owned half an acre where the mill formerly was (it seems the mill was not there at that time.45

The mill house remained on the premises until July 4, 1855, when it was destroyed by fire while the rest of Dorchester celebrated the 225th anniversary of the settlement of the town. Later during the excavation of the South Bay, pieces of old planks, which had been used in the construction of the dam, were taken out.46

Amusingly, the family genealogy says an account from a descendant of that Samuel Clap states that Samuel lived in Northampton, Mass., where he owned a tidemill.

Glover’s Tide Mill, mid- to late-19th century at Glover’s Corner, the intersection of Dorchester Avenue and Hancock and Freeport Streets.

Dorchester 1850 map - Whiting, E. Map of Dorchester, Mass.

Surveyed by Elbridge Whiting for S. Dwight Eaton (Old Colony R. R. Depot, Boston). (Boston, 1850)

Detail from Bradley, W. H. Plan of Neponset River and Part of Dorchester Bay Showing the Harbor Lines. (Boston, 1854)

Detail from Bradley, W. H. Plan of Neponset River and Part of Dorchester Bay Showing the Harbor Lines. (Boston, 1854)

A deed dated in 1831 from one Alexander Glover to another described the property as a wharf, saw mill and bark mill. By the the 1860s it was described as a planing mill. The 1850 Dorchester taxable valuation shows Alexander Glover (estate) had a mill and privilege. Alexander Glover III’s biography says he was a cabinet maker, carpenter and manufacturer of pumps. In 1867 William Glover 2nd and Edwin Jones acquired the property with the tide mill at Glover’s Corner. William Glover of the firm Glover and Jones was listed as a cabinet maker in the 1874 Boston directory.47

Breck Mill/William Robinson/Tileston Mill, 17th century

Dorchester 1850 map - Whiting, E. Map of Dorchester, Mass.

Surveyed by Elbridge Whiting for S. Dwight Eaton

(Old Colony R. R. Depot, Boston. (Boston, 1850)

Dorchester 1850 map - Whiting, E. Map of Dorchester, Mass.

Surveyed by Elbridge Whiting for S. Dwight Eaton (Old Colony R. R. Depot, Boston. (Boston, 1850)

The map has a black circle with a cross in it on the north side of Mill Street (the dam on Tenean Creek). The circle represents the mill that was then owned by the Tileston family. A National Guard armory now sits at the site on Victory Road (formerly Mill Street) on the former Tenean Creek, now all filled in.

The tide-mill at Tenean Creek was built by Edward Breck who probably came to Dorchester in the second migration in 1635, and he purchased land of Mr. Burr in 1642. Breck lived on Adams Street. Town records for December 17, 1645, state “There was given to Edward Breck, by the hands of most of the inhabitants of the town, Smelt Brook Creek, on the condition that he doth set a mill there.” 48 He built the mill, and the street on which it stood was later called Mill Street [renamed Victory Road during the first World War when a bridge was built to Quincy to accommodate workers traveling to the naval air station there]. William Robinson acquired the mill, possibly as early as 1646.49 Robinson sold a half interest in the mill to Timothy Tileston in 1664 for 96 pounds.50 The description at that time was: a “little house” and ten acres of land on “Tide-Mill Creeke, and half a corn water-mill standing on the tide in the creeke, commonly called Salt Creeke or Brooke, near Captaines Neck.” In 1668 Robinson, the second owner, died when he was “drawn through by ye cogwheel of his mill, and was torn in pieces and slain.” 51 Since he died after the sale of the mill, he may have been working at the mill after he sold it, or he may have still owned a partial interest in the mill.

Lease agreements were generally written for a term of seven years. In 1686 an agreement was executed for improving the said mill for the space of seven years next ensuing, stating that “we have mutually agreed to the several articles hereafter expressed first it is agreed and concluded that Timothy Tileston shall himself or by some other miller tend the said mill during the time above said so that customers may be encouraged and not discouraged by ill grinding or otherwise, and that the said Tileston shall and will at his own proper cost and charge bush the mill stool and sharpen the bils, wedge the gugons and mend the water wheels by putting in of staves and rowellboards and ladles when and as need may be and to put in cogs and rounds except when they are to be new set. Timothy Foster having rounds turned and cogs split shall at his cost put them in workman like. 2ndly the said Tileston shall render unto his partner or his assigns or order one fourth part of all the profits of said mill only in mault and in mault three pecks in eight and as to all public charges of rates to be payd three fourth by Timothy Tileston and one fourth by Timothy Foster and finally Timothy Tileston shall and will in case of Timothy Foster’s absence if any breaks shall be made in the dam take all care to stop the same which he shall be paid for according to satisfaction which is mutually agreed to be the one half part of all the charges that shall arise during the said term of seven years either in the mill wheels or stones dams and every other charge that shall arise in or about said mill that is not above expressed and excepted; the above said partners likewise agree that both their corn for them and spendings shall be ground toll free.” 52

Some of the documents mention shares in the mill, and as generations went on, ownership became more and more distributed. The Lease dated July 6, 1772 lease from Elisha Tileston to Nathaniel Tileston includes the wording: it being one half and five sevenths of two thirds of a quarter of ye sd mill. A person who has a greater interest in mathematics than I explained that to figure out the formula, one should start at the end. Take 2/3 of a 1/4, then take 5/7 of the result and then 1/2 of that result. I don’t know if this works, but if you figure it out, please let me know.

Henry N. Blake wrote: “I was born in a one-story building of wood on the southwestern side of Mill Street in Dorchester, (now Boston), Massachusetts, on the fifth day of June, 1838. On the opposite side of the street was a grist mill of the old style, owned by Ebenezer Tileston and my father. A story was added to the building, which is standing in good repair, but the mill and creek flowing into it have been filled recently with rubbish by the city of Boston. This was an ancient privilege, granted by the Massachusetts Colony in 1645; the grantee and his successors were authorized to construct and maintain a dam across an arm of the sea from Massachusetts Bay. The power was furnished by the incoming tide which flowed into the pond and closed the gate when it receded.

My father was the miller and worked in the night or daytime according to the ebb and flow of the tide. The payment for grinding corn and grain was fixed by law and the miller had the right to take for his services a certain portion of each grist called “tolls,” but the parties agreed sometimes upon a sum of money. When I was young I enjoyed many hours playing about the mill, caught fish and learned to swim in the pond and dug clams at low tide in the creek.” 53

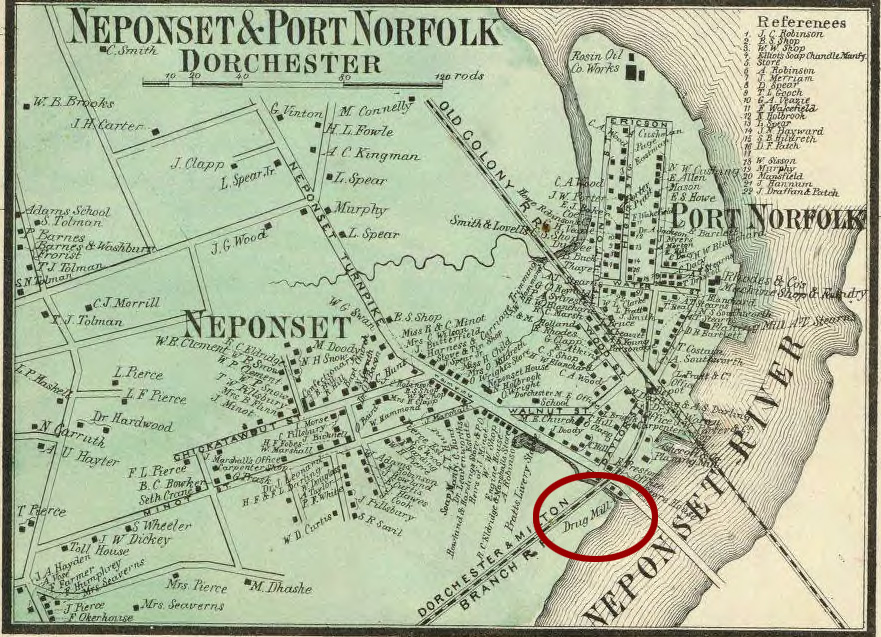

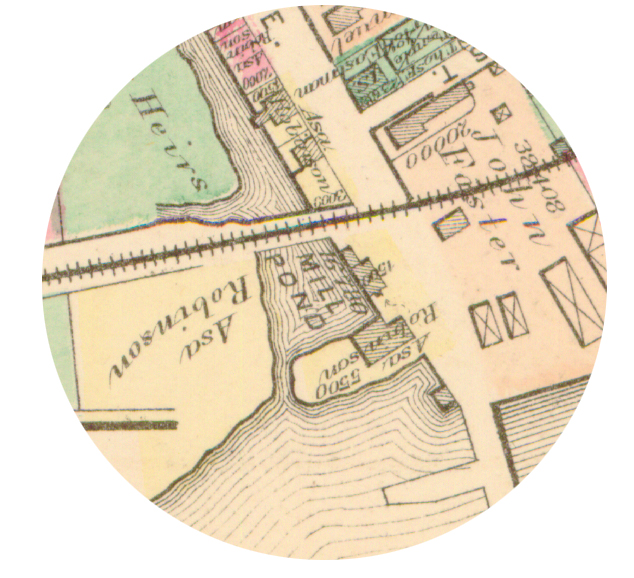

Asa Robinson Tide Mill - Late 19th Century on the Neponset River Estuary

Dorchester 1850 map - Whiting, E. Map of Dorchester, Mass.

Surveyed by Elbridge Whiting for S. Dwight Eaton

(Old Colony R. R. Depot, Boston. (Boston, 1850)

Walling Map of Norfolk County, 1858 from www.DavidRumsey.com

The 1858 Walling Map of Norfolk County indicates that the mill operated by Asa Robinson was a drug mill.

On April 30, 1845, Asa Robinson granted to William Pierce, tallow chandler, half an interest in the salt marsh land at the Neponset Turnpike and the right to cut a ditch and draw water from Davenport’s creek for the use of a mill which Pierce and Robinson proposed to erect near Neponset Bridge.54

Hopkins, Griffith Morgan, Jr. Atlas of the County of Suffolk, v. 3 including Boston and Dorchester. Plate N. (Philadelphia: G. M. Hopkins, 1874)

When Asa Robinson sold a lot of land to John Donovan on Oct. 14, 1884, and another lot to Donovan on March 18, 1885, Robinson specified: The lot hereby conveyed is a portion of the canal leading to Robinson’s Tide Mill and is conveyed subject to the restriction that so long as said tide mill is maintained, no structure shall be erected upon the premises hereby conveyed, except on piles or posts and such manner as not to interrupt and obstruct the free passage and flow of the water to said mill.55

Aerial View of Neponset Circle and Neponset River

- photograph of Neponset Circle, Dec. 18, 1935 by Fairchild Aerial Services. - courtesy of Emy Thomas.

The 1935 photograph shows the remnant of the tide mill site. This location was approximately where the Neponset Drive-In Theatre stood and is now part of Pope John Paul II Park.

Quincy

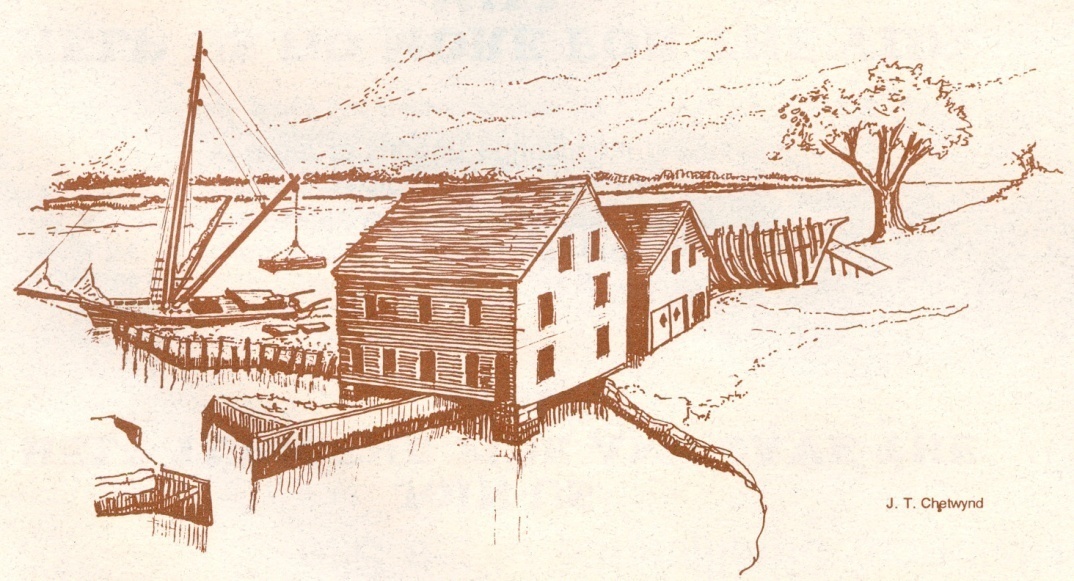

Souther Mill Illustration - courtesy of Joseph Chetwynde

The illlustration by Joe Chetwynde shows the grist mill next to the dam and the saw mill building next to it.

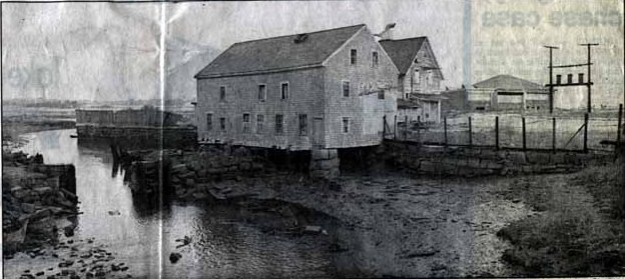

Souther Mill photograph showing both grist mill and saw mill - https://southertidemill.org/

Souther Mill - courtesy Earl Taylor

The following is from John Goff’s Preservation and Management Plan for the Souther Tide Mill.

About 1806 Ebenezer Thayer built a dam on an inlet of the Town River and created a large salt water millpond eight or nine feet deep at each high tide. This tidal grist mill was a major agricultural landmark in the early community because it was used by local farmers to grind a variety of grains into meal, flour and bran.

In 1814 Thayer sold land and the mill to David Stetson, and Stetson sold to John Souther the following year. John owned the mill until 1845, when he conveyed it to his son Henry.56 Prior to the arrival of the railroad, Henry Souther did a good business at the Souther Tide Mills grist mill. Extensive amounts of grain were brought to the mill by ship and cart and were processed to create a wide assortment of flours, meals, and brans. Henry South had bought out his junior partner, Micah Humphrey, and was sole proprietor of the “old stand” Souther’s grain store at the corner of Washington and Coddington Streets. The Souther shipyard did a bustling business, launching schooners, brigs , stone sloops and an occasional full-rigged ship. A saw mill near the grist mill cut logs into plank and boards.

Industry and prosperity halted abruptly in December, 1846. Shortly before Christmas that year, Henry Souther received news that both the tidal grist mill and the tidal saw mill were destroyed by fire. An unidentified “incendiary”—possibly a new urban drunk & disorderly—torched the buildings in the night, and the valuable complex with its contents was proved to be a near-total loss come morning. Henry Souther had been insured adequately for his customers’ lost grain, but he had inadequate coverage to replace the wood industrial buildings.

The project to rebuild the grist mill was further supported by the fact that the fire had not burned the whole mill privilege entirely. The dam, stone wharves, first floor framing, and some of the first floor planking survived in good enough shape to be re-used. Charred evidence of that horrible fire still exists on the underside of the mill in the first floor framing and on the underside of old floorboards, which were flipped and re-used. The pre-1846 tidal saw mill was not rebuilt until some thirty years later.

Around 1875 Joseph Loud & Company became a tenant in the grist mill. Loud owned a feed store operation near the Quincy railroad depot and had earlier been associated with the Southers in helping them import grain and export cornmeal by railroad. Following the Civil War, Loud installed a new steam-powered grist mill in his downtown store. According to Fenno, this single action by Loud effectively ended the Souther tidal grist mill’s long career as an operating grist mill both because the Souther mill could not compete commercially with the new steam power and because Loud was located closer to the Old Colony Railroad. The Southers apparently made the best of the situation by securing Loud as a long-term tenant.57

The Souther Tide Mill is the last of four tide mills known to have been built in Quincy, representing the continuation of a local historical tradition that its roots in the 17th century.

Conclusion

Why have tide mills not survived?

All water mills were unable to compete when other methods of generating power became available. Steam and then electricity were more efficient. A few mills were converted to the new methods of generation. For river mills, water supply was sometimes sketchy in dry summer months, and in winter fresh-water mill ponds can freeze over. For tide mills, the salt water in the tide mill pond seldom froze, but the miller’s schedule of operation was limited to about 6 or 7 hours in every 12-hour period, not to mention the varying schedule of the tides every day. Water-powered mills could not compete.

The reason for the disappearance of tide mill buildings and ponds was their value for new uses. Boston’s need for ever-increasing development resulted in land making along all its shoreline. The architectural style of tide mill buildings was often uninspired, and the modest appearance of tide mill buildings did not recommend them as significant historic sites. The buildings were designed simply for the use of milling. In most cases, construction standards of earlier years could not satisfy evolving building codes, and their re-use was not financially attractive. The dark green area on the map represents the land as it existed in 1630, and the lighter green areas represent made land. The making of land pushed the shoreline way beyond the location of the tide mills. so that the former sites of mills and ponds are now lost in urban areas, nowhere near waterways. Tide mill sites and ponds have been covered over and obliterated by Boston’s need to expand.

The geographical outliers in this presentation are the Slade Mill building in Revere and the Souther Mill building in Quincy, and it is partly their location that has contributed to their survival. By the time the pressure of profit created a desire to redevelop these areas outside the central city, the historic significance of the sites was recognized.

Notes:

1. Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge. Edited and with Commentary by Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge. Edited and with Commentary by Richard A. Duffy (Arlington, 1999). Original novel published 1882. Duffy’s commentary provides a history of the Woods mill.

2. Smith, Thomas P. The Spice Mill on the Marsh. (Norfolk Downs, Mass.: Pneumatic Scale Corporation, 1925), 7.

3. Chamberlain, Mellen. A Documentary History of Chelsea including the Boston Precincts of Winnisimmet, Rumney Marsh, and Pullen Point, 1624-1824. (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1908).

4. Smith, 9-10.

5. Smith, 15-17.

6. Smith, 21.

7. “The Colonial Slade Mill - Foundation of a Spice Empire.”http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-colonial-slade-mill-foundation-of-a-spice-empire/

8. Cutter, William R. “The Cutter Family and Its Connection with a Tide Mill in Medford.” Medford Historical Society Papers, vol. 2.

9. Massachusetts. An Act to Enable Certain Persons to Use the tide Waters Between Chelsea and Deer Island for Certain Purposes. For the purpose of improving ad working a newly invented Floating Tide Mill. 1826. Private and Special Statues of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, from May 1822, to March 1830 v. VI (Boston:, 1837), 560-561.

10. Meigs, Peveril. “Energy in Early Boston.” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 128 (April, 1974), 85.

11. “Medford/s First Gristmill.” The Medford Historical Register, 23 (1920), 58.

12. Sketch of the Recent Improvements at East-Boston. January, 1836. (Boston: J. T. Buckingham, 1836) and Sumner, William H. A History of East Boston; With Biographical Sketches of Its Early Proprietors. (Boston: J. E. Tilton, 1858)

13. “In One Corner of Medford.” Medford Historical Register, 13.4 (October, 1910), 98.

14. “The Mills on the Medford Turnpike.” Medford Historical Register, 23.1 (March, 1920), 21.

15. Ibid, 21.

16. Brooks, Charles. History of the Town of Medford, Middlesex county, Massachusetts, from Its First Settlement in 1630 to 1855. Revised, enlarged, and brought down to 1885, by James M. Usher. (Boston: Rand, Avery U Company. The Franklin Press., 1886), 386.

17. Cutter, William R. “The Cutter Family and Its Connection with a Tide Mill in Medford.” Medford Historical Register, 3.3 (July, 1900), 131.

18. Brooks, 386.

19. “Medford’s First Gristmill.” Medford Historical Register, vol. 23.3 (September, 1920), 54-55.

20. Stevenson, C. L. Report on Tidal Investigations in Mystic River and Pond. (Boston, 1861), 7.

21. Brooks, 393.

22. Medford Historical Register, vol. 21, no. 1, January, 1918 (Medford, 1918), 65.

23. Stevenson, 7.

24. Richard Duffy. The Tinkham Brothers Tide Mill by J. R. Trowbridge. Edited and with Commentary by Richard A. Duffy (Arlington, 1999). Original novel published 1882. Duffy’s commentary provides a history of the Woods mill.

25. Mann, Moses W. “Wood’s Dam and the Mill beyond the Mystic.” Medford Historical Register. XII (January, 1909), 13-20.

26. Frothingham, Richard. The History of Charlestown, Massachusetts. (Boston: Little and Brown, 1845), 115.

27. Meigs, Peveril. “Energy in Early Boston.” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 128 (April, 1974), 84-85. For the Revolutionary War claim Meigs cites James F. Hunnewell. A Century of Town Life: A History of Charlestown, Mass., 1775-1887. (Boston, Little, Brown & Co., 1888), 151.

28. Seasholes, Nancy S. Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003), 392.

29. Seasholes, Nancy S., 403.

30. Winsor, Justin, editor. The Memorial History of Boston, Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts. 1630-1880. Vol. I. (Boston, 1881), 225, 533. Massachusetts Historical Commission Archaeological Exhibits http://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcarchexhibitsonline/millpond.htm

31. Seasholes, 79-80.

32. Marchione, Wiliam P. “Building the Mill Dam.” Brighton Allson Historical Society website. [http://www.bahistory.org/HistoryMillDam.html] This article appeared in the Allston-Brighton Tab or Boston Tab newspapers in the period from July 1988 to late 2001.

33. Marchione.

34. Marchione.

35. Meigs, Peveril. “Energy in Early Boston.” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 128 (April, 1974), p 8.

36. Marchione.

37. Mapping Boston. Edited by Alex Krieger and David Cobb. (1999), 124

38. Mapping Boston, 126.

39. Drake, Francis S. The Town of Roxbury: Its Memorable Persons and Places. (Roxbury, 1878), 325.

40. Clapp, Ebenezer. The Clapp Memorial: Record of the Clapp Family in America. (Boston, 1876), 210.

41. Clapp Memorial 92.

42. Clapp Memorial 92-93.

43. Clapp Memorial, 197.

44. Clapp Memorial, 210-211.

45. Clapp Memorial, 212.

46. “Old Grist Mill at Willow Court.” in Dorchester Beacon? (ca. 1910). History of the Town of Dorchester, Massachusetts. (Boston, 1859), 290-291

47. Biographical Sketches of Representative Citizens of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (Boston, 1901), 1065) re: Alexander Glover; Boston Directory 1874 for William Glover 2d; Dorchester. Taxable Valuation 1850; Goff, John. Our Clapps and their Old Dorchester Mills & Tanneries. Typescript (2008). Alexander listed as a cabinet maker in Dorchester and Milton Business Directory for 1850.

48. Dorchester. Dorchester Town Records. Fourth Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston 1880. Second edition. (Boston, 1883)., 57.

49. Ferris, Mary Walton. Dawes-Gates Ancestral Lines: A Memorial Volume. (1943), 528.

50. History of the Town of Dorchester, Massachusetts. (Boston, 1859), 88, 108, 132-133, 177. Meigs, 85. Harris, Edward Doubleday. William and Anne Robinson of Dorchester, Mass. Their Ancestors and Their Descendants. Boston, 1890), 4.

51. Harris, 4. Harris cites Rev. John Eliot’s Diary, but perhaps he meant the Roxbury Church records mentioned in “Rev. Samuel Danforth’s Records of the First Church in Roxbury, Mass.” New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 34 (July, 1880), 299.

52. Lease owned by Dorchester Historical Society.

53. Blake, Henry Nichols. “Memoirs of a Many-Sided Man: The Personal Record of a Civil War Veteran, Montana Territorial Editor, Attorney, Jurist.” Montana, the Magazine of Western History. (Autumn, 1964). Written in 1916. Edited by Vivian A. Paladi..

54. Norfolk County, Massachusetts. Registry of Deeds, Book 154, p. 172.

55. Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Registry of Deeds, Book 1654, p. 543-544. Book 1670, p. 236.

56. Norfolk County. Massachusetts. Registry of Deeds, Book 47 Page 147; Book 50, Page 93; Book 154, Page 129.

57. Goff, John. The Souther Tide Mill of Quincy, MA: A Brief History & Its Significance. Typescript. (2008). Goff, John. Souther Tide Mills, Quincy, Massachusetts. Preservation and Management Plan. 2 vols. Prepared for the City of Quincy, Massachusets by Historic Preservation & Design. (1995). Other sources include: Historic American Engineering Record for Souther Tide Mill Dam and History of Souther Tide Mill transcribed from, Quincy History, Winter 1981 issue by the late H. Hobart Holly, a publication of the Quincy Historical Society. https://southertidemill.wordpress.com/history/

Tom Dahill and Bill Kuttner at the Winter Meeting of the MCA

MISCELLANY

Back Issues - More than 50 years of back issues of Towpath Topics, together with an index to the content of all issues, are also available from our website http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath. These are an excellent resource for anyone who wishes to learn more about the canal and should be particularly useful for historic researchers.

Back Page - Excerpt from an August,1818, drawing (artist unknown) of the Steam Towboat Merrimack crossing the original (pre-1829) Medford Aqueduct, probably on its way to service on the Merrimack River.

Estate Planning - To those of you who are making your final arrangements, please remember the Middlesex Canal Association. Your help is vital to our future. Thank you for considering us.

Museum & Reardon Room Rental - The facility is available at very reasonable rates for private affairs, and for non-profit organizations to hold meetings. The conference room holds up to 60 people and includes access to a kitchen and restrooms. For details and additional information please contact the museum at 978-670-2740.

Museum Shop - Looking for that perfect gift for a Middlesex Canal aficionado? Don’t forget to check out the inventory of canal related books, maps, and other items of general interest available at the museum shop. The store is open weekends from noon to 4:00pm except during holidays.

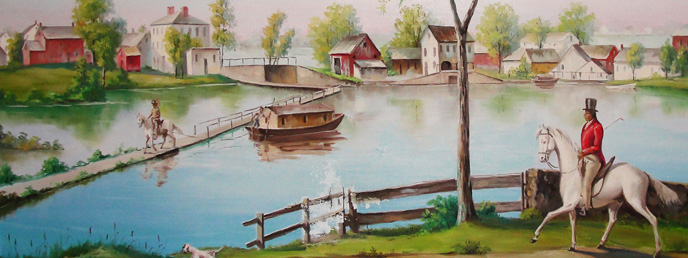

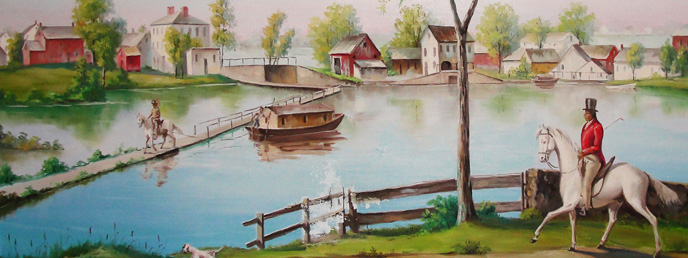

Nameplate - Excerpt from an acrylic reproduction of a watercolor painted by Jabez Ward Barton, ca. 1825, entitled “View from William Rogers House”. Shown, looking west, may be the packet boat George Washington being towed across the Concord River from the Floating Towpath at North Billerica.

Web Site – The URL for the Middlesex Canal Association’s web site is www.middlesexcanal.org. Our webmaster, Robert Winters, keeps the site up to date. Events, articles and other information will sometimes appear there before it can get to you through Towpath Topics. Please check the site from time to time for new entries.

Officers & Directors of the Middlesex Canal Association: 2018-2019

Officers of the Middlesex Canal Association J. Jeremiah Breen, President Traci B. Jansen, Vice-President Russell B. Silva, Treasurer Neil P. Devins, Membership Secretary Howard B. Winkler - Corresponding Secretary |

Directors of the Middlesex Canal Association Betty M. Bigwood Thomas H. Dahill, Jr. Debra Diffin Fox (TT copy co-editor) Roger K. Hagopian - Videographer Alec Ingraham (TT copy co-editor) Alan D. Lefebvre Robert Winters (webmaster, TT publisher) |

Honorary Directors William E. (Bill) Gerber Leonard H. Harmon Fred Lawson, Jr. Jean M. Potter |

MEMBERSHIP

| Proprietor (voting) | $25 per year |

| Member (non-voting) | $15 per year |

Additional contributions are always welcome and gratefully accepted. Please make check out to the: Middlesex Canal Association and mail it to: Neil P. Devins |

The first issue of the Middlesex Canal Association newsletter was published in October, 1963. Originally named “Canal News”, the first issue featured a contest to name the newsletter. A year later, the newsletter was renamed “Towpath Topics.”

Towpath Topics is edited and published by Debra Fox, Alec Ingraham, and Robert Winters.

Corrections, contributions and ideas for future issues are always welcome.