Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 60 No. 3 | May 2022 |

“May the Eye of Wisdom and the Eternal Mind aid this work designed for the benefit of the present & Future Generations.”

Prayer: Loammi Baldwin, September 10, 1794, Billerica Massachusetts

This image represents the design for the façade of the new MCA museum building

at 2 Old Elm St, Billerica MA, site of the groundbreaking 228 years ago.

Photo courtesy of Christina McMahon, AIA, Caveney Architectural Collaborative

MCA Sponsored Events – 2022 Schedule

Spring Meeting, 1:00pm, Sunday, May 15, 2022

Speaker: Eric Hutchins, fisheries biologist, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Topic: Talbot/Billerica Falls Dam

Riverfest, MCA Museum in North Billerica – June 18-19, 2022

10:00am – Walk the Thoreau Path

Noon-4:00pm – Tentative Oxen Exhibit

For more details check the SuAsCo Riverfest 2022 Calendar for updates

20th Annual Fall Bicycle Tour North, 9:00 am, Saturday, October 1, 2022

Meet at the Middlesex Canal Plaque right of the entrance to the Sullivan Square T Station, 1 Cambridge Street, Charlestown, MA 02129

Leaders: Dick Bauer and Bill Kuttner Helmets Required

Fall Walk, 1:30pm, Sunday, October 16, 2022

Meet at the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center, 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862

for a three mile walk south along the canal to the smallpox cemetery, a round trip of less than three miles

Fall Meeting, 1:00pm, October 23, 2022

Lecture: TBA

The Visitors Center/ Museum is open Saturday and Sunday, Noon – 4:00pm, except on a holiday (April 17, 2022, Easter).

The Board of Directors meets the 1st Wednesday of each month, 3:30-5:30pm, except July and August.

Check the MCA website for updated information during the COVID-19 pandemic.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MCA Sponsored Events and Directions to the MCA Museum and Visitors’ Center

President’s Message: “Enchanted Land, NPS Lowell” - by J. Jeremiah Breen

2022 Winter Meeting of the MCA Report

Spring Walk Report - by Robert Winters

Gift of a Bench - by Betty M. Bigwood

Sunday, April 24 Canal Bike Ride Report - by Bill Kuttner

A Comparison of the Blackstone and Middlesex Canals … by B. H. Dickson

(reprinted from Towpath Topics #6-1) with a brief biography of the author by Alec Ingraham

Editors’ Letter

Dear Readers,

The return of spring is such a welcome time of the year. Flowers, bushes, trees blooming always seem brighter than the year before, but maybe they aren’t, but at least it is a liberation from the brown and snow!

This issue starts off with President Breen’s message and reports of the Winter Meeting and Spring Walk. Betty Bigwood has written about the Memorial Bench for long-time Association member, Carolyn Osterberg.

The main article is something promised in previous issues, a reprinting from a past Towpath Topics issue. This one is a lively back-and-forth account of the Middlesex and Blackstone Canals. To add to this story, Alec Ingraham has done his own research on the life of the author, B. H. Dickson and is asking for comments on Mr. Dickson from readers who might remember him.

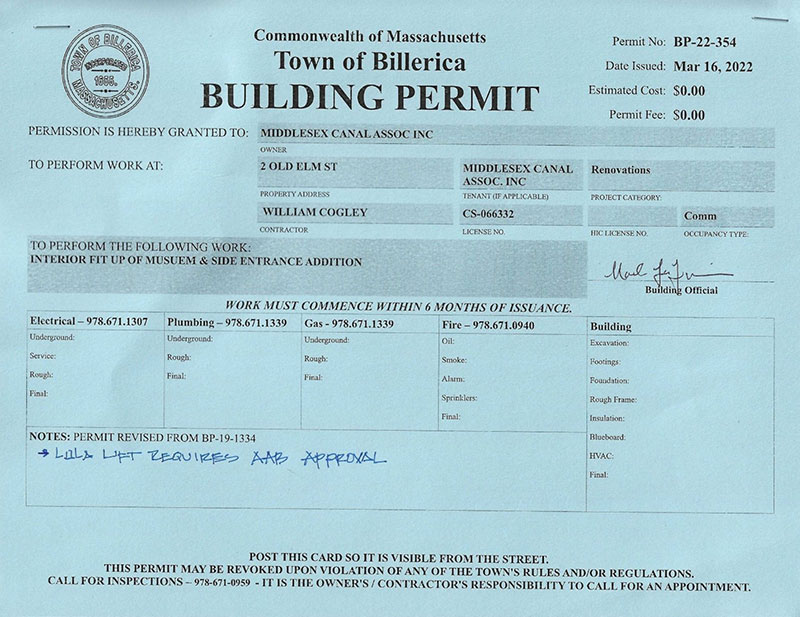

Lastly, some may say the highlight of the issue is a photo of the SIGNED building permit for 2 Old Elm Street. Let the future begin!

Enjoy! — The Editors (Deb, Alec, and Robert)

MCA Sponsored Events

Spring Meeting: 1:00pm, Sunday, May 15, 2022. Eric Hutchins will provide an update on the status of the Talbot Mill/Billerica Falls Dam since the publication of the December 2016 Fish Restoration Study, https://rb.gy/3mbvqd. For more information on the meeting and as to the method of communication (ZOOM and/or live), please access the MCA website a week before the scheduled date of the meeting.

Walks and Bicycle Tours: For more detailed information please access the MCA website at www.middlesexcanal.org about a week prior to the scheduled event.

Directions to Museum: 71 Faulkner Street in North Billerica, MA

By Car

From Rte. 128/95

Take Route 3 (Northwest Expressway) toward Nashua, to Exit 78 (formerly Exit 28) “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at the fork. After another ¼ mile, at the traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A (Boston Road). Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road (Talbot Avenue) which will put St. Andrew’s Church on your left. Go ¼ mile to a stop sign and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the bridge over the Concord River, where Old Elm Street becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the bridge. Watch out crossing the street!

From I-495

Take Exit 91 (formerly Exit 37) North Billerica, then south roughly 2 plus miles to the stop sign at Mt. Pleasant Street, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700’ and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street (Faulkner Street). To get to the Visitor Center/Museum enter through the center door of the Faulkner Mill and proceed to the end of the hall.

By Train

The Lowell Commuter line runs between Lowell and Boston’s North Station. From the station side of the tracks at North Billerica, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station Street and Faulkner Street on the right side.

President’s Message – “Enchanted Land, NPS Lowell”

by J. Breen

A yolk of oxen pictured with a young child |

The National Park Service at Lowell National Historical Park presented a program. “Irish Canal Builders”, this spring. The Association president gave a talk April 3, 2022 as a part of the program on two subjects, This Enchanted Land: Middlesex Village, a tragic novel by Wayne Peters, published in 1984, and the necessity of water transportation for the success of Lowell cotton factories.

This Enchanted Land describes Middlesex Village and the canal in 1823 and 1833. The plot is an homage to Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome, published in 1911. The talk April 3rd had a filmed enactment of tragic climaxes by Billerica Access Television (BATV), directed by Tara Splingaerd, of the three protagonists with the Middlesex Canal, the latter very much a part of the mise en scène, 880 megabytes, available at www.middlesexcanal.org/photos, [https://rb.gy/daz7dc], until BATV uploads the April 3 talk to the Internet Archive.

The necessity of water transportation, the Middlesex Canal, to the economics of Lowell was that other cotton mills had water transportation with its ten-to-one advantage compared to wagons hauling 400 lb. bales of cotton on rutted, hilly, dirt roads. Dover NH for example had competing mill supplied by gundalows on the Piscataqua River.

The president was part of the discussion panel April 10 at the NPS Lowell Visitor Center. Lowell had a system of boarding houses to attract workers. The Middlesex Canal had barracks. The duties of an appointed steward were to provide food and lodging for employees. Lodging was straw beds and bunks. Food was beef, fish, rum and sugar, vegetables, chocolate, Bohea tea. See “Duties of the Steward” from the Old Middlesex Canal, Mary Stetson Clarke, p. 36. When the Irish canal builders went to work in 1822, they built shanties and cooked their own food. The National Park Service offered $150 as an honorarium for the Association’s participation in the canal builders’ program.

The Massachusetts Cultural Council has granted the Association $1,500 for tow animals, a petting zoo?, to be part of Concord Riverfest 2022. Plan is to have a pair of oxen on display near the canal at 2 Old Elm St, June 18, noon - 4pm.

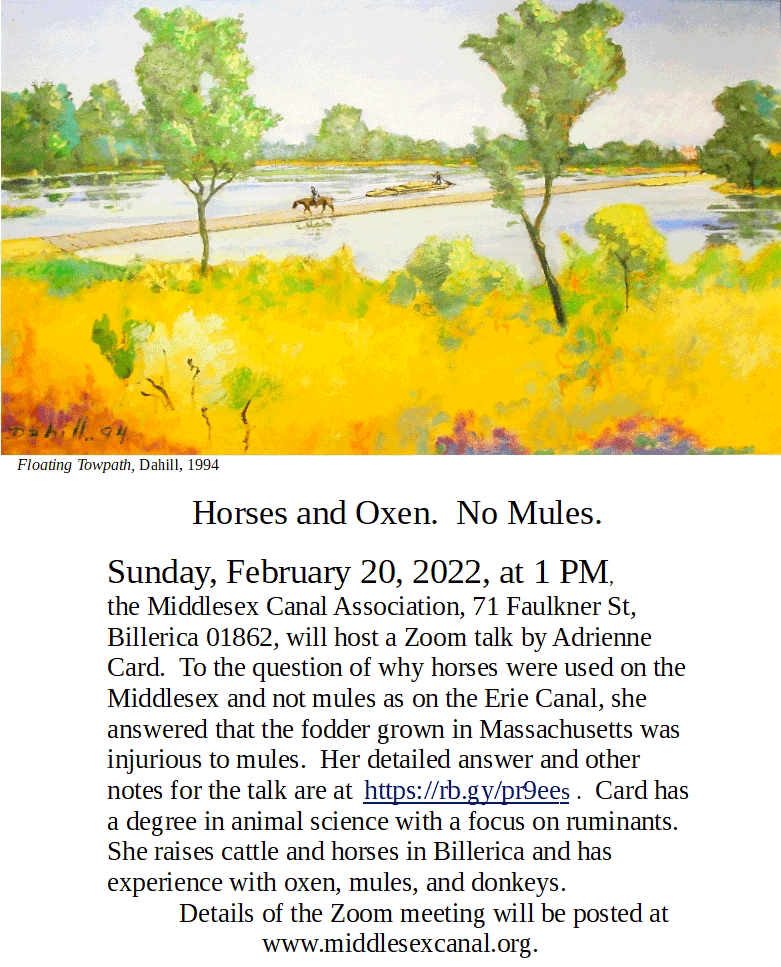

February 20, 2022 Winter Meeting Middlesex Canal Association Report

Door to Lenore & Howard Winkler’s Zoom meeting room opened at 12:30pm. J. Breen, Chair ex officio, called the Zoom meeting to order at 1:00pm. No member of the Association raised a hand to speak or ask a question of the directors.

Adrienne Card gave a talk on “Horses and Oxen. No Mules” and answered questions for more than an hour.

A video of the meeting is online at http://www.middlesexcanal.org/photos/ in J Breen’s folder, or directly at https://rb.gy/cqfbbc.

Spring Walk Report

by Robert Winters

On March 20, 2022, about 26 participants (and a dog) joined walk leader Robert Winters for our Spring Walk in Billerica/Chelmsford starting at our Museum in North Billerica. After introductions we were able to check out the interior of our new museum - and the new deck overlooking the Concord River and the anchor stone that was once upon a time held the northern end of the floating towpath across the river. The interior of the building still has a way to go before it can be occupied, all the permits are now in place and it’s just a matter of time.

We next gathered around the lock remnants across the street from the new museum before scrambling along the canal route to where the Red Lock once allowed boats to transfer between the Middlesex Canal and Concord River below the falls. We then walked along the canal segment that runs along Lowell Street to Boston Rd (Route 3A). Though we would normally proceed next along McLennan Way, the work of the beavers made this impossible, but we were able to use a workaround via Alpine Street to get back to the canal and followed that to beyond Brick Kiln Rd. Once again, those pesky beavers made further passage impossible through the Chelmsford Water District and along Canal Street to what would have been our turnaround point at Riverneck Road. Perhaps in the future there can be made some accommodation through the often-flooded relatively short segment so that our walkers and others could better enjoy the full walk. Our route back was along Alpine Street, Lowell Street, and Old Elm Street back to our starting point at the Museum.

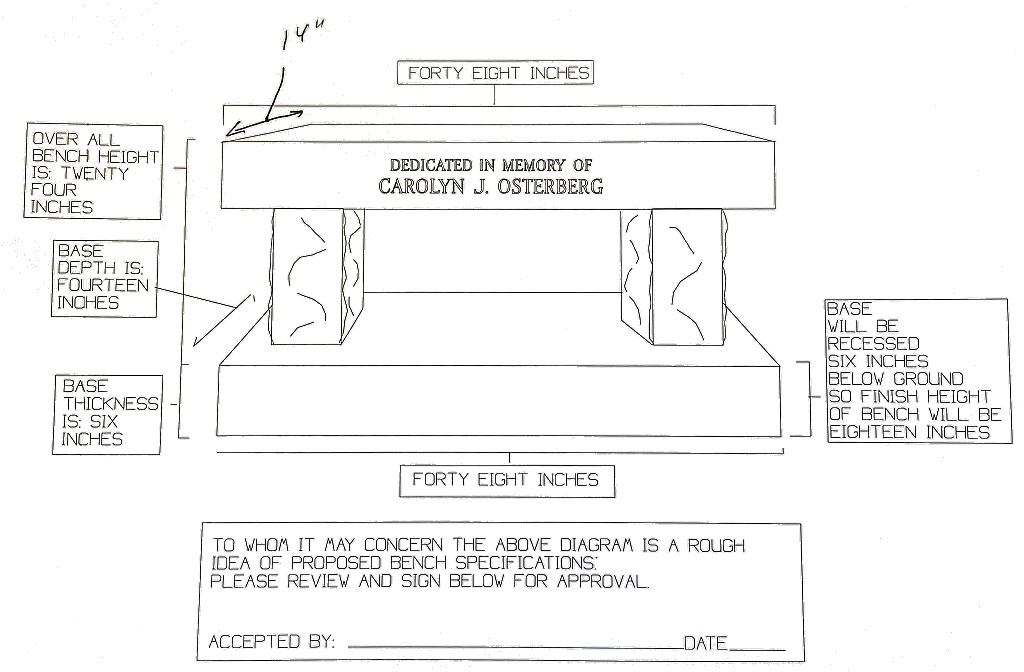

Gift of a Granite Bench

by Betty M. Bigwood

Neil Devins and Karol Bisbee, April, 2022 Picture courtesy of Betty Bigwood |

Carolyn Osterberg was a long-time member of the MCA. She was fortunate to own four acres of land which had a long stretch of canal running along its border. I had long wished to have a walk along the berm which would connect Lake Street with her property on Nichols Street. We spoke about it on numerous occasions but Carolyn was hesitant to make a formal deed restriction. I had already completed the first half of the connective walkway with Developer Stuart and he agreed to name his driveway Jaques Lane, in honor of Samuel Jaques who--- was a Wilmington resident and replaced Loammi Baldwin as the second Superintendent of the Middlesex Canal Corporation for one year.

Carolyn has lived in a nursing home since her dementia began about five years ago. Her home was sold and I have worked with the Town Conservation Agent, Valerie Gingrich, to continue the walkway. Unfortunately, the developer backed out and the process will start again. I would have preferred to have the bench on her property but with the development in limbo that was not possible.

Carolyn has been very fortunate in having an Attorney, Karol Bisbee, who specializes in Eldercare. Karol and Julie Pomodoro, a nursing aide, have made sure that Carolyn has been treated well. They have become very interested in having a memorial bench made in honor of Carolyn and approached us to share their plan. As you walk along the canal it will be delightful to have a place to rest. Neil Devins, Karol and I decided that the best place would be off Butters Row and midway on land that we own to put the bench. It will be installed the end of May.

Sunday, April 24 Canal Bike Ride Report

by Bill Kuttner

Riding the MBTA’s Lowell commuter rail line has always been a practical, fun, and educational element of the spring and fall bicycle canal explorations. Spring rides begin in Lowell, with riders from Boston arriving by one of the morning trains. The ride goes all the way to Boston, but riders wishing to leave early for any reason can meet one of the Lowell Line trains at an intermediate station.

The rail line itself is historical, having been surveyed by George Whistler (father of painter James Whistler) in 1835 while he was chief engineer for the Proprietors of Locks and Canals in Lowell. This historic corridor is undergoing a major improvement as a pair of Green Line tracks are being constructed next to the two commuter rail tracks between east Somerville and Tufts University.

Prominent sandwich-style signboards in North Station had announced that buses would replace weekend train service at North Station on the Lowell Line for several weeks up to Sunday, April 17. Good. Our April 24 ride, marked on our schedules for many months, was a go as planned. On Thursday, April 21, the MBTA website now noted that buses would replace trains at North Station on April 23 and 24. Had I misread the signs? A quick visit to North Station saw the numbers “23” and “24” taped over the ending dates on the weekend service signboards. The signs also ominously warned that the buses “cannot accommodate bicycles.” The fine print on the signs still showed April 17 as the last day of suspended train service.

A new ride notice was quickly sent out announcing a new ride starting point: Anderson Station in Woburn. Jimmy Anderson was the 12-year-old boy who died of leukemia in 1981, subject of a famous environmental liability case made famous by the book and film A Civil Action. The toxic waste was from local tanneries, one of history’s dirtiest industrial processes.

Eight riders board the 10:51 train at Anderson Station. Seven have arrived at Anderson by car and one rider rode from Somerville. Three additional riders drove or rode to Lowell meet the train from Anderson at 11:15. Your author had mentioned to some people verbally that they might join him on the 8:30 train from North Station, so he was there to meet them just in case. Seemingly on his own, Paul Revere Transportation was perfectly happy to allow use of the standard bike rack affixed to the front of their bus. So much of official pronouncements. (There was a Plan B.)

Our group of twelve headed directly to the National Park Service reconstructed Pawtucket locks. The three canal types visited in the ride were previewed:

1. A navigation canal used by river-borne traffic to bypass rapids.

2. Power canals, or millraces, that bring water to operate water turbines.

3. A navigation canal that connects two watersheds, the Middlesex Canal.

The Pawtucket Canal was contemporary with the Middlesex Canal and eliminated a cumbersome portage around the Pawtucket Falls, improving navigation between Newburyport and New Hampshire. The ride then proceeded through the historic mill district to the Merrimack River, viewing several power canals on the way. Riding on the path next to the river we reached the base of the Pawtucket Falls. Climbing the power “head” (the number of feet of drop for waterpower) we viewed the large Northern Canal and the electrical generating station it still powers.

One more element of the Lowell canal system remained before reaching the Middlesex Canal corridor: Francis Gate. Completed in 1850, this gate paid for itself many times over in 1852 when it was dropped to protect Lowell and the mills from the rising Merrimack. It was dropped again in 1936. Roosevelt was president. The river still powered the mills, Francis Gate again protected the city, and WPA commissioned engineers to conserve elements of the Middlesex Canal that we would later view.

A mile of two up the Merrimack and we were at Old Middlesex Village, the location of the flight of three locks that dropped the Middlesex Canal to allow entry into the Merrimack River. The logic of the original canal alignment was explained: Lowell did not exist except as a mere portage point. The economic imperative was to connect Boston with New Hampshire, and this was the best point to bet canal boats onto the river for the next leg of their journey.

From this point forward we were tracking the canal route as best we could given the extensive infrastructure that has since overlayed the route. Our next stop was a vantage point above the Mount Pleasant Golf Club. An elongated water trap forms a gentle arc through the fairways. Of course, this was the Middlesex Canal.

President Jay Breen shared an intricate path that used the Bruce Freeman rail trail to reach a canal remnant adjacent the former Wang Towers, veritable coking furnaces of the Computer Age. From here it was almost direct to the museum in North Billerica. Thanks to the beaver population, the scenic route through the Chelmsford Water District is not passable. The tow path from brick Kiln Road to Route 3A is . . .barely.

The museum is worth a visit all its own, but we mostly rested a bit and planned the next move. Three riders left the group: one by train to Lowell, one by bike to home nearby, and the third had a prearranged pickup. The remaining nine left, zigging and zagging across the Billerica-Tewksbury boundary until we reached Route 129. Then it’s a race to the Shawsheen Aqueduct, still the high point of any ride. This is a fine example of the WPA historic preservation efforts.

The group then split with a group of seven riders pushing to the oxbow at the Wilmington Town Park, and the other two riders opting for a slower pace. After the oxbow the next stop was Loammi Baldwin’s statue across the street from his mansion near Route 128. Four riders needed to find Anderson Station, but two riders simply rode on to Somerville. Your author guided the group to the Anderson lot where their cars were parked, and then rode back to Charlestown rather than wait for a bus. Maybe this time they would have refused to carry a bicycle.

A Comparison of the Blackstone and Middlesex Canals

[Reprinted from Towpath Topics Vol 6: #1]

by B.H. Dickson

By the 1790’s, inland waterways had proved their merits in industrial England and Americans were beginning to recognize them as an important means of transportation. About this time two major projects were conceived - the Middlesex Canal from Boston to Lowell and the Blackstone Canal from Worcester to Providence. The Middlesex began operating in 1803 but the Blackstone didn’t get going until 25 years later – a delay that proved disastrous. The reason for the delay was lack of cooperation on the part of the Massachusetts Legislature in granting the Blackstone its charter. The idea of a canal connecting Boston with the Merrimack River and diverting the great natural resources of New Hampshire away from Newburyport and into Boston met with wholehearted approval in the capital city; however, the idea of the landlocked treasures of Worcester County making their way to market through Rhode Island, and seeing Providence benefit from business that rightly belonged to Boston, was unthinkable. When the Blackstone Canal finally got its charter in 1823, Bostonians dreaded more than ever the evil effects of such a waterway. A few months before it was completed, the Boston Centinal issued a stern warning: “If the canal is not counteracted by some similar enterprise in this town, Boston will be, in a very few years, reduced to a fishing village.”

The situation was somewhat alleviated, three years after the canal went into operation, by the Boston and Worcester Railroad getting its charter. The president of the House of Representatives who signed the enacted bills was a gentleman by the name of Leverett Saltonstall.

During the first twenty years of the nineteenth century a number of canals were proposed to keep Boston from becoming commercially stagnant, among them one from Boston to Worcester to counteract the Blackstone, another from Boston to the Connecticut River to divert traffic away from the Farmington and another from Boston to Troy, New York, to get a share of the Erie Canal business for Massachusetts. It is interesting to note that the route surveyed for this last project is very much the same as the route of the Boston and Albany Railroad. The surveyors recognized the necessity of tunneling through the Berkshires. To get over them would require 220 locks. These would not only consume an enormous quantity of water but it would take a boat two days to get through them, while a four mile tunnel would only take an hour and twenty minutes. The location they chose was where the Hoosac Tunnel was bored many years later. The canal surveyors estimated the cost at less than a million dollars; actually, it cost over 10 million, which would have been the financial ruin of any canal company. All sorts of unforeseen obstacles kept cropping up, more and more money had to be raised and each raising was accompanied by the usual legal complications. At one point some frustrated party remarked that he knew a way of finishing that tunnel in no time – just put a group of lawyers at one end and a large fee at the other.

When the Blackstone was finally completed the Middlesex was a well-established institution and enjoying its era of greatest natural prosperity – natural because its biggest money-making days had an unnatural impulse behind them – namely, construction of the Boston and Lowell Railroad. Rails, ties and other building materials were transported to their respective destinations on canal boats – and finally, the British-built locomotive traveled by boat to Lowell to be assembled in the machine shops there. It has been said that the Middlesex Canal, “like an accusing ghost . . . seldom strays far from the Boston and Lowell Railroad to which it owes its untimely end.”

The Middlesex Canal operated nearly 32 years unharassed by railroad competition – the poor Blackstone, only 7. An original investor in the Middlesex Canal, by retaining his interest, would have recovered 75% of his money; a Blackstone investor, $2.75 and the privilege of subscribing to stock in the Blackstone Canal Bank. The canal has been called the “greatest financial fiasco in the history of Providence.”

The Blackstone was beset with other difficulties that didn’t affect the Middlesex. For water it depended on a source that was already earmarked for manufacturing. Many establishments had sprung up along the line during the years of delay and in order to assure an adequate water supply for the canal, reservoirs had to be provided. Unfortunately the increase in supply fell far short of requirements – especially as more and more mills began using the water. The Middlesex, on the other hand, had its own mill pond in North Billerica, formed by a dam in the Concord River. There was no competition with industrial establishments on the sluggish Concord. For 21 miles upstream from the millpond the rise was only 3½ feet. According to Henry Thoreau, the only bridge ever washed away on this section was blown upstream by the wind.

Now compare this head of less than 2 inches per mile with the Blackstone’s 10 feet per mile and you can see why the water power potentials of the latter were early recognized and utilized. Though “a very Tom Thumb of a river, as rivers go in America,” according to the Technical World, the Blackstone is, “the hardest working ... the one most harnessed to the millwheels of labor in the United States, probably the busiest in the world.”

The Middlesex Canal, except for where it crossed the Concord River at its North Billerica reservoir, was confined to its own ditch for its entire length. Except for months when it was frozen over, uninterrupted service could be maintained. The Blackstone used slack water navigation in the river for about one-tenth of its distance. This involved entering and leaving 16 times. During periods of low water the boats would get stranded on the river shoals and during periods of flood the river sections were too swift to be navigated. Clients had to wait for days or even weeks at a time for delivery or pick-up of freight. Worcester warehouses bulged with stranded merchandise. As time went on merchants got more and more disgusted with these interruptions to service and, with the canal being closed 4 or 5 months in winter on account of ice, they naturally sought more reliable means of transportation.

However, none of these difficulties were anticipated. When the canal stock was offered in Providence there was a wild scramble for it and within three hours it was oversubscribed. Messengers were quickly dispatched to Worcester to see if any additional stock could be picked up there, but when they arrived, they found that the Worcester quota had also been oversubscribed. Those who were not allotted any stock little realized, at the time, how fortunate they were!

There was no wild scramble for Middlesex Canal stock. In those days American canalling was in its infancy and the stock had a speculative flavor. But by the Blackstone’s time, canals had proved themselves to be a growing and reliable form of transportation and the shares a promising investment.

The Middlesex was a pioneering enterprise and a courageous undertaking. It penetrated a countryside of sparse population – Medford, Woburn, and Chelmsford small villages – Lowell non-existent while Boston itself was a town of but 20,000. The Santee Canal in South Carolina, the only one to antedate the Middlesex, was still under construction. Pennsylvania canals, for which surveys were being made, were still very much on paper and the Erie only a dream. When the route for the Middlesex was first laid out surveying and leveling instruments were unknown in New England. Loammi Baldwin of Woburn, the chief engineer, and Samuel Thompson of the same town spent a week making elevations by a method Thompson had devised which consisted of squinting along a carpenter’s level and making laborious calculations. His mistakes were amazing, to say the least. For instance, he estimated that the Concord River in Billerica was 161 feet lower than the Merrimack at Middlesex Village where the canal would enter it. Actually, it was 25 feet higher, or an error of 41 feet in 6 miles!

Perhaps the best thing that came out of this original survey was the Baldwin apple. While working in Wilmington the surveyors noticed an unusual number of woodpeckers all apparently flying towards a certain spot. On investigation they found a wild apple tree with unusually good fruit. Baldwin, the engineer, did much to propagate and promote this apple. At first it was called the pecker apple on account of the woodpeckers.

The directors realized that an accurate survey would be necessary before proceeding with the construction of the canal and they sent Baldwin to Pennsylvania to consult an Englishman named Weston who was surveying for canals there. Mr. Weston consented to come to Massachusetts and survey for the Middlesex. Baldwin wrote back that “Mrs. Weston has more than once expressed a passionate desire of visiting Boston and has frequently told me that she longed to be acquainted with ladies and gentlemen of that metropolis. She observed that all English gentlemen and ladies enjoyed themselves better in Boston than any place on the continent. I daresay that in my important business this is a very trifling circumstance to report to you – however, I declare that almost my only hope of securing Mr. Weston’s assistance . . . rests on this circumstance.” It was Mr. Weston’s levels that inspired confidence in the feasibility of the canal.

By the time the Blackstone came along, the art of leveling and surveying was pretty well established here. The company employed a Benjamin Wright who, they said, was “a skillful engineer under whose superintendence and estimates, the middle section of that stupendous work, the Erie Canal was constructed.” His big mistake, as already mentioned, was using slack water in the river. Experience had earlier demonstrated to DeWitt Clinton and others that this sort of thing was not practical. Perhaps it was done for the sake of economy. However, there was no penny-pinching in construction of the locks. With one exception, they were all made of hand cut granite and there were 48 of them. The 28 locks on the Middlesex Canal, with the exception of three, were originally made of wood and they were all eventually replaced with stone. The Blackstone engineers undoubtedly bore this fact in mind in deciding against wood.

Construction of both canals was by hand labor – picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. It took 9 years to build the Middlesex; the Blackstone took only four. Building the Middlesex was a constant succession of trial and error – finding the proper lining to make the ditch watertight, devising a method for making hydraulic cement, etc. The ingenious Baldwin overcame all these obstacles in the end but they all took an abnormal amount of time – at least that was the opinion of the weary stockholders who grew tired of assessment after assessment with no prospect of any immediate return on their money.

In 1797, 6 years before the canal was completed, the management, in an effort to cheer the stockholders, ordered the opening of the 6-mile section between the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Baldwin protested violently but he was over-ruled. The passengers embarked on two horse-drawn barges. As they proceeded along the canal the workmen marched beside them on either bank carrying their tools over their shoulders; they had received instructions from a notice that stated in part, “It is requested that the dress of the workmen be decent and clean, their movements active but regular, their behavior civil and respectful; in short their general conduct such as shall do honor to themselves and those concerned will consider themselves honored thereby.” Once through the locks at Middlesex Village, the passengers disembarked and walked over to Howard’s Tavern for a handsome feast, and as they walked they passed between two rows of workmen still “martially holding their tools.”

Over the next few years excursions were held on this section from time to time to console discouraged stockholders and impress prominent citizens. The boats were decorated “gaudier than a circus wagon” to add cheer to an otherwise drab situation.

No such junkets were necessary on the Blackstone. By now the technology of canal building was established and hopeful stockholders saw no delays other than those caused by the whims of the weather – or perhaps an occasional personnel problem. A few months before completion the following appeared in the paper, “The unusual supply of rain descending in continual showers, has been particularly unfavorable to the progress of the work. The contractors have been delayed in their operations by the fountains and streams bursting from the earth shadowed by constant clouds, and poured down from every hillside.”

The first excursion, a ten mile trip from Providence, took place 3 months before the canal was opened for its entire length. Passengers embarked on the “Lady Carrington,” a very grand and beautiful vessel. She had a “palatial cabin running most of the length of her body, which was “conveniently and neatly arranged.” She was painted white and had red curtains in her windows and left Providence July 1, 1828 amid “a salute of artillery ... seconded by the cheers of those on board and the shouts of hundreds of spectators who crowded the banks and surrounding eminences.” There was a band of music aboard of 8 or 10 pieces. The trip was most successful.

On a second excursion 3 days later, a man was sitting on the railing telling a story when suddenly the boat struck the canal bank and he went overboard. After being pulled back in, all wet through, he shook himself off and resumed his place on the railing and said “as I was saying,” and continued with the story as if nothing had happened.

With the opening of the canal the “Lady Carrington” took passengers from Worcester to Providence or towns along the way but it was never a successful competitor with the stage coach. The trip took 14 hours with sometimes an overnight stop, either spending the night at a canal tavern or using sleeping accommodations aboard the boat, while the stagecoach left at 8 in the morning and arrived at 5 in the afternoon. However, the boat was considered “a pleasant conveyance for invalids who desire to travel or to take the sea air.”

The Middlesex Canal did a more successful passenger business. The trip to Middlesex Village took 7 hours and it connected with a ferry to Boston on the Charlestown end and a stage to Lowell on the upper end – that is, after Lowell became a place of some consequence. When the canal was dug there was no Lowell - just a small settlement known as East “Chumsford” (translated: Chelmsford). Lowell didn’t become a great textile center until several years later. The most pretentious of the passenger liners was the `Governor Sullivan’ sometimes referred to as the `General Sullivan.’ It had a carpeted cabin and upholstered seats and was considered a model of comfort and elegance. It was towed by two horses at a trot and had right of way over all other craft. The passenger on the Governor Sullivan was “protected by iron rules from the dangers of collision; undaunted by squalls of wind, realizing, should the craft be capsized he had nothing to do but walk ashore . . . (he) . . . had plenty of time for observation and reflection.

When the textile mills were built on the Merrimack, large quantities of coal and raw materials were shipped to them from Boston and finished goods returned, using canal transportation in both directions. But at first, cargos were represented primarily by granite, lumber and agricultural products from the Merrimack Valley and vicinity. For many years, the shipyards on the Mystic River and the Navy Yard at Charlestown relied on the canal for the greater part of the lumber they used in shipbuilding. With locks around the various falls on the Merrimack, a vast area was opened up, Plymouth, N. H. being the upper limit of river navigation.

On the Blackstone Canal, cargos shipped to Worcester included such commodities as salt, lime, coal and lumber. Soon after it opened a local paper announced that, “a quantity of cherry plank and joists was landed in this town ... which grew in Michigan or Ohio at the head of Lake Erie, from which it was shipped down the lake to Buffalo thence by the Erie Canal to Albany, from that place to Providence by sloop navigation and from Providence to this place by the Blackstone Canal – a distance ... of at least 900 miles, four hundred of which is artificial navigation. It is thus that articles are made valuable in one section of the country where otherwise there would be no market for them, and another section is supplied at a fair rate with that which it must otherwise do without or buy at . . . exorbitant prices.”

Cargos that came overland to the Port of Worcester to be shipped out by canal included dairy products, agricultural products, chairs and coal from the Worcester coal mine. When the canal was built it was expected that this coal would contribute substantially to profits. Professor Hitchcock in his Geology of Massachusetts said of the coal, “it will be considered by posterity, if not by the present generation, as a treasure of great value.” It was considered “suitable for furnaces where intense heat and great fires are required.” It received much publicity in the local papers. For instance, “Captain Thomas has fitted up a stove for burning it in his bar room where for about a week past, he has not used a particle of any other fuel, and has had as handsome and as good a fire as we have ever witnessed of either the Lehigh or Schuylkil coal.” It’s possible that these opinions were influenced by a touch of what Capt’n Thomas served in his bar room.

In developing the mine a shaft was driven 300 feet into the hill and at one time 20 men were employed there. However, when Col. Amos Binney, its chief promoter, died it was closed and the mineral “which might be made to give motion to the wheels of manufacturing . . . has been permitted to rest undisturbed in its bed.” People who used the coal, the publicity notwithstanding, were inclined to feel it vastly overrated. One user caustically remarked that the residual ash weighed more than the coal itself!

The Blackstone had not been operating many months when boatmen discovered that short hauls were the most profitable – especially in stretches with fewer locks. Worcester people felt neglected. The inhabitants, the newspaper said, “have derived but little benefit from the canal during . . . the last fortnight, although they had hundreds of tons of freight which they were anxious to get up. The reason is that all the boats now on the canal can be more profitably employed in doing the business of the lower end of the route. We hope our citizens will take measures to have a regular line of boats from this place early in the spring.”

On the pleasanter side, there were excursion boats that took passengers on holiday jaunts. One of the better remembered was a picnic in Waterford where the Congregational Society of that town played host to the Uxbridge Congregational Society. “So together with many from North Uxbridge they made a goodly number. They went by canal. The boat was decorated with festoons and evergreens and . . . a kind of bannerette . . . called Gideon’s Lamp.” The trip took three hours and progress was so slow that many of the passengers got out and walked. At one sharp turn the boat nearly upset. When they got to the picnic spot there was a scarcity of lunch. “The Uxbridge guests expected the Waterford people to furnish the repast so went without any food. The Waterford people evidently did not so intend their invitation, so when lunch time came the Uxbridge people were not invited to partake with them.” One of the passengers came to the rescue and bought a barrel of crackers and a quantity of cheese out of which the Uxbridge people made their lunch.

On the Middlesex Canal, Horn Pond in Woburn was a favorite place to go on a holiday, being readily accessible from Boston by boat. Pleasure barges took passengers on scenic trips around the lake while “Kendall’s Brass Band and the Brigade Band of Boston rendered sweet harmony and the crowds wandered from the groves to the lake and back to the canal where shots of lumber, rafts and canal boats were continually passing through the locks.”

One young lady, writing in her diary about a trip to Horn Pond, mentions stopping near some water lilies. Some of the ladies expressed a desire for them and Daniel Webster, who happened to be aboard, remarked “If I was a young man, I should not let a young lady ask for those flowers in vain.” Whereupon two gallant men “dashed into the lake and wading about gathered a number of lilies, brought them to shore and distributed them at the great risk of their health as they were obliged to wear their wet clothes the rest of the afternoon. Fortunately, they were attired in black silk or stuff pantaloons which were not injured in appearance.” The diary also states that the young lady’s mother considered it very thoughtless of Mr. Webster to say what he did and to encourage the young men to run the risk of pneumonia.

The Blackstone had one thorn in its side that the Middlesex managed to avoid – sabotage. There were constant disputes between boatmen and millowners. The millowners said that the canal was using too much water – the boatmen maintained, and correctly, that there wouldn’t be all that water there except for the reservoirs built by the canal company. As early as 1829, the second year of operation, the embankment of a canal feeder near Millbury was destroyed by some laborers in the employ of a manufacturing establishment. The event received much adverse publicity and the embarrassed millowner, who had ordered the work done, made reparation. As time went on, sabotage became less and less of a transgression and millowners openly indulged in it. In order to conserve their dwindling water supply they sometimes dumped large stones into the locks by night, rendering them inoperative; the boatmen retaliated by threatening to burn the mills and armed guards had to be hired to prevent any such disaster.

Tolls on the Blackstone reached their peak in 1832 – 3 years before completion of the Boston and Worcester Railroad. That year nearly $19,000 in tolls was collected – rather a puny figure when you consider that the canal cost $750,000. They also paid the first and biggest dividend that year – $1.00. Receipts slumped badly with the advent of the railroad and continued downward during the remainder of the canal’s existence. The last toll was collected in 1848, a year after the canal was dealt a fatal blow by the advent of the Worcester and Providence Railroad. Passengers could now make the trip in 2 hours instead of 14 by boat or 9 by stagecoach. The canal could operate from an hour before sunrise until an hour after sunset; the railroad could run at night. When the Boston and Worcester Railroad went into operation 13 years earlier, night railroading was not permitted except when unavoidable. Locomotives were not equipped with headlights. Once a train got delayed outside Worcester and had to complete its journey after dark. The engineer reported, “ran into some cattle at 9 P. M. and killed two of them. It was so dark, could not see.”

Tolls on the Middlesex reached a peak in 1833. The figure reflected business stimulated by construction of the Boston and Lowell Railroad. That year a dividend of $30.00 a share was paid but with it came this note of warning, “In a short time a large part of the tolls will be paid to another corporation.” Three years later, in 1836, the canal lost its Lowell tonnage to the railroad, but continued to operate reasonably profitably for another 6 years by which time the railroad had been extended to Concord, N. H.; and after that tolls rapidly faded out until 1853 when the last one was collected.

When abandonment appeared inevitable a scheme was proposed for using the ditch as an aqueduct to bolster Boston’s diminishing water supply. “If the canal cannot put out the fire of the locomotive,” Caleb Eddy, the manager wrote, “it may be made to stop the ravages of that element in the city of Boston.” Boston wells were going dry and the water in them was becoming contaminated. “One specimen,” Eddy wrote, “which gave 3% animal and vegetable putrescent matter, was publicly sold as a mineral water; it was believed that water having such a remarkable fetid odor and nauseous taste could be no other than that of a sulfur spring; but its medicinal powers vanished with the discovery that the spring arose from a neighboring drain.”

The Concord river water had been analyzed by “four of the most distinguished and able chemists in the country, all of whom agree that it is in every respect of the requisite purity for drinking and for culinary and for all other purposes.” One of these distinguished chemists became even more distinguished later – his name was Professor Webster and he murdered Dr. Parkman in his Cambridge laboratory and disposed of the body in his incinerator.

Not only would Boston benefit from this project; also, vast tracts of meadowland in Wayland and Sudbury could be restored, if the flashboards on the Billerica dam were removed. This dam had been enlarged during a modernization program in 1830, causing water to back up over the Sudbury meadows and ruining, according to one authority, 10,000 acres of the most valuable meadowland in the state. This figure increased substantially over the years with silting from the sluggish stream. Considerable litigation had brought no benefit to the proprietors of the Sudbury meadows as there was a clause in the Middlesex Canal charter that couldn’t be surmounted. When the aqueduct proposition failed the canal faced abandonment. It had been, as one of its original proprietors put it, “A magnanimous enterprise.”

Today portions of canal and towpath can still be seen, especially in Billerica and Wilmington but each year a little more becomes obliterated by the bulldozer as it levels the ground for real estate development. Two aqueducts, one in Billerica and the other in Wilmington have been spared destruction.

Parts of the Blackstone can also be seen. In Pawtucket, several miles of canal and towpath are being preserved as a recreational park. One lock still remains almost intact – a fine example of the labor and skill that went into hand cut granite. When the canal was abandoned, the other locks were dismantled and sold for building stones.

The Blackstone has been spoken of as a “magnificent enterprise.” “To the Providence and Worcester Railroad it was a sort of forerunner, hinting at the grades, furnishing a path, and opening an avenue for the transportation of heavy freight . . . every town along the whole line is deeply indebted to it for the present growth and prosperity.”

Had it been built 25 years earlier and confined to its own ditch it probably would have been a very lucrative enterprise even after the advent of the railroad. By controlling water rights on the river and selling power to the mills it could have continued prosperous even though the form of transportation it offered had become outmoded.

Upon completion of the Providence and Worcester Railroad a toast was given at a meeting in Worcester, hinting at the relative importance of the two methods of transportation – “The two unions between Worcester and Providence. The first was weak as water, the last as strong as iron.”

_______________________________________________

Editors’ Note

Brenton H. Dickson III

by Alec Ingraham

Brenton Halliburton Dickson III was born in Weston, MA on November 10, 1903, the son of Brenton H. Dickson, Jr. and Ruth Bennett Dickson. Following his course of study at the Noble & Greenough School in Dedham, he graduated from Harvard University in 1927. A year later he married Helen Sumner Paine (1904-2003) of Weston. He subsequently received a Master’s Degree in Chemistry from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His WW II draft card indicates that in 1941 he was working as a chemist for the Nazon Laboratories in Cambridge. The couple for many years lived on Love Lane in Weston, MA and had three daughters and one son.

As a life-long resident of Weston, Brenton was involved in many civic organizations. He was a founding member and board historian of the Weston Historical Society until his death. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Weston Historical Commission, a member of the Weston Centennial Commission, and a trustee of the Golden Ball Tavern.

Aside from chemistry his interests included music, history and the arts. He wrote many articles and books many of which are still available online. Some of his major works include “Our Town in the American Revolution: Weston,” “Massachusetts and Random Recollections,” “Of Pungs and People,” and “Early Automobile.”

Brenton was a pianist and composer. He wrote the music and lyrics for several plays which were produced by the First Parish Family Society of Weston. He even participated as an actor. A copy of the program for one of his musicals can be found online, even today. If this were not enough to occupy his time, he was an amateur geologist and owned several mines in New England and maintained a vast collection of minerals. Brenton was an accomplished artist as well. He painted water colors, many of rural New England. His paintings were displayed in a variety of shows and exhibits even as late as the year 2000, at an exhibit at the Weston Library.

He was a gifted and popular speaker particularly on the topic of the 19th century industrial revolution in Massachusetts. Although his primary residence was in Weston, Brenton owned a summer home on Manchester -by-the-Sea. He owned several yachts and was a member of the Manchester Yacht Club. During the winter he was an avid skier and was a charter of the White Mountain Ski Runners. Later in life he and his wife took up birdwatching. He took pictures of the birds and both were members of the Massachusetts Audubon Society and the National Audubon Society. Other memberships included the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Sierra Club, the Boston Symphony, the Somerset Club and the St. Botolph Club. After a productive, useful, and well lived life Brenton passed away on August 29, 1988.

The Middlesex Canal did not escape his attention. Brenton wrote an article entitled “The Middlesex Canal” which is included in Vol. 40 of the Cambridge Historical Society’s 1964-1966 collection on pages 43-58. During the early years of the MCA’s existence as an organization Brenton was member at the proprietor level. In addition to writing the article “Comparison of the Blackstone and Middlesex Canals” which is reprinted in this edition of Towpath Topics, (The article also appeared in the Old-Time New England, Bulletin of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Vol.58, #4 April/June, 1968) he also was the primary guest speaker on two occasions. On March 12, 1967, he gave an illustrated talk on his recent trip along the English Canals and at the Winter Meeting on February 2, 1969 he spoke and showed pictures of a second overseas trip to the canals of the English Midlands.

Bibliography:

Weston Historical Society Bulletin: Vol. XXII; #1 December, 1988.

Boston Globe, August 31, 1988, Page #47.

Towpath Topics Vol. 5; #1 March, 1967, Vol. 6; #2 September, 1968, Vol. 7; #1 January, 1969 and Vol. 8; #2 April, 1970.

Middlesex Canal Bibliography from Middlesex Canal Phase IV Report, 2007

The editors would appreciate receiving any information from the membership concerning Brenton or the topic of his essay. Does anyone recall attending his lectures? Were they interesting? It has been over half a century since Brenton wrote his comparison of the Blackstone and Middlesex Canals. Much has changed since 1968, if anyone is interested in commenting or updating the article, please contact the editors.

MISCELLANY

Back Issues - More than 50 years of back issues of Towpath Topics, together with an index to the content of all issues, are also available from our website http://middlesexcanal.org/towpath. These are an excellent resource for anyone who wishes to learn more about the canal and should be particularly useful for historic researchers.

Estate Planning - To those of you who are making your final arrangements, please remember the Middlesex Canal Association. Your help is vital to our future. Thank you for considering us.

Membership and Dues – There are two categories of membership: Proprietor (voting) and Member (non-voting). Annual dues for “Proprietor” are $25 and for “Member” just $15. Additional contributions are always welcome and gratefully accepted. If interested in becoming a “Proprietor” or a “Member” of the MCA, please mail membership checks to Neil Devins, 28 Burlington Avenue, Wilmington, MA 01887.

Museum & Reardon Room Rental - The facility is available at very reasonable rates for private affairs, and for non-profit organizations to hold meetings. The conference room holds up to 60 people and includes access to a kitchen and restrooms. For details and additional information please contact the museum at 978-670-2740.

Museum Shop - Looking for that perfect gift for a Middlesex Canal aficionado? Don’t forget to check out the inventory of canal related books, maps, and other items of general interest available at the museum shop. The store is open weekends from noon to 4:00pm except during holidays.

Nameplate - Excerpt from an acrylic reproduction of a watercolor painted by Jabez Ward Barton, ca. 1825, entitled “View from William Rogers House”. Shown, looking west, may be the packet boat George Washington being towed across the Concord River from the Floating Towpath at North Billerica.

Web Site – The URL for the Middlesex Canal Association’s web site is www.middlesexcanal.org. Our webmaster, Robert Winters, keeps the site up to date. Events, articles and other information will sometimes appear there before it can get to you through Towpath Topics. Please check the site from time to time for new entries.

The Canal the Bisected Boston: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3yvlBAPGmg

The Middlesex Canal (1793-1860), dug by hand from the Merrimack River at Middlesex Village in Chelmsford to the Charles River at Charlestown during the second term of George Washington’s presidency, played a major role in the development of Boston. Boats were drawn by horse to the Charles River. There they were pulled by chain across the Charles River and down Mill Creek, which bisected the city, to the long wharfs of Boston Harbor. Written and narrated by David Dettinger, author of the definitive study of the Canal extension in Boston from 1810-1830. — Videotaped and edited by Roger Hagopian

The first issue of the Middlesex Canal Association newsletter was published in October, 1963.

Originally named “Canal News”, the first issue featured a contest to name the newsletter. A year later, the newsletter was renamed “Towpath Topics.”

Towpath Topics is edited and published by Debra Fox, Alec Ingraham, and Robert Winters.

Corrections, contributions and ideas for future issues are always welcome.

We end this edition with good news!

At long last the building permit necessary to complete the construction of the new

MCA Museum in the repurposed Talbot Mill cloth warehouse has been obtained.

Congratulations to the Building Committee: Betty, Dick, Tom and J.