Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

Middlesex Canal Association P.O.

Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 47 No. 1 |

October 2008 |

President’s Message

by Nolan Jones, President

603-672-7051, <ntjones at dragon dot mv dot com>

At our annual meeting in May we were honored to have Lance Metz, Historian from the National Canal Museum in Easton, PA, as our guest speaker. Lance is a remarkable fellow and an entertaining speaker. He presented newly discovered movies of old canal operations.

This is repetitious, but again we think that we are nearing completion of our application for the National Registry of Historic Places recognition. Massachusetts Historic Commission (MHC) approved the application more than a year ago. We have been sorting out small details identified by the MHC staff since then.

Photo by Howard Winkler

Lance

Metz, Historian,

National Canal Museum

We are about to mail letters to our 1400+ “neighbors”, who either own pieces of the canal or abut the route. The program for the fall meeting will be a slide tour of the canal route as it exists today.

In an article that appeared in the September 2007 issue of Towpath Topics, Alan Seaburg reported on the creation of the Middlesex Canal Association’s Endowment Fund. As of this issue, the Fund has received $33,450 in gifts, and all of these funds are invested in Fidelity Balanced Fund. Our thanks to all who have contributed, and may your generosity continue to grow the fund.

We continue to respond to requests for talks to various groups. I will meet with a retired group in Nashua, NH, and the Medford Historical Society. Bill Gerber will be presenting his ‘John L. Sullivan and his Development of the Steam Towboat’ talk to the New England Model Engineering Society during their November 6th meeting at the Charles River Museum of Industry. Bill will make this same presentation at the Canal History and Technology Symposium, to be held at Lafayette College in March 2009.

A portion of Boston’s Big Dig surface beautification effort will include a small park with the story of the Middlesex Canal and its extension into Boston. The park will be at the end of Canal Street, adjacent to the new Hines-Raymond building. Directors Bigwood, Dahill, Dettinger and Raphael are working with the designers of the project which may take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Two education committee members received a grant from the JMR Barker Foundation to develop an educational outreach program. This project will update the current curriculum guide, develop a self guided museum tour using audio technology, purchase classroom materials, design and build an interactive museum exhibit, and build relationships with local schools and teachers. The project hopes to bring a large number of young students to the museum and encourage their interest in local archaeology, history, engineering and business.

Because of light museum attendance during past summers we split the schedule in two. This fall, the museum is open from September 6 through November 23 on Saturdays and Sundays from 12 to 4 p.m. The museum is open at other times and dates by appointment.

If you have not visited the museum we encourage you to do so. If you would like to help, we do need more docents. This is an easy way to learn more about the canal.

-- Nolan

TABLE OF CONTENTS

President’s Message (Nolan Jones)

Calendar of Events

Middlesex Canal Commission - Summary Report (Tom Raphael)

Spring MCA-AMC Canal Walk (Roger Hagopian, Robert Winters)

The Future of Our Museum (Alan Seaburg)

Letters, First Published ... Boston Daily Advertiser (Howard Winkler)

William Weston ... Contribution to Early American Engineering

About Billerica ... Beginning ... Nineteenth Century (Marshall)

Out for a Walk along the Canal with my Dad (Proctor)

The Old Middlesex Canal – 1898 (Houser)

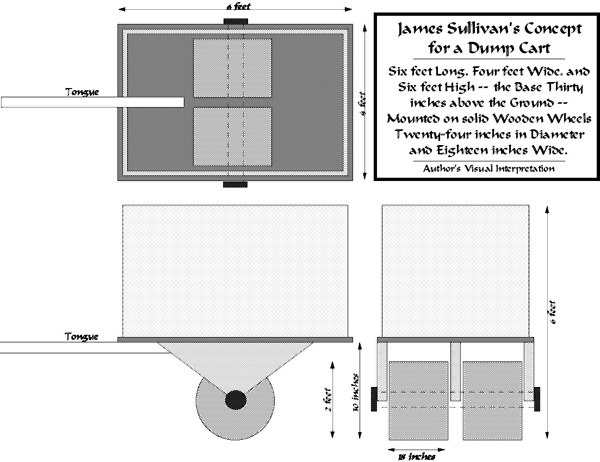

Early Tools for Moving Earth (Bill Gerber)

Photos and Miscellany

Calendar of Events

Middlesex Canal Association and Related Organizations

First Wednesday - MCA Board of Directors’ Meetings - The BoD meets, from 3:30 to 5:30pm, the first Wednesday of each month from September to June. Members are welcome to attend.

Sept 6 to Nov 23 - The Middlesex Canal Museum, 71 Faulkner St., N. Billerica, will open to the Public, Free of Charge, Saturday and Sunday, 12 to 4 PM, between these dates.

Oct 13-18 - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal through bike ride, Cumberland to Georgetown. Contact Tom Perry at 301-223-7010.

Oct 17-19 - Pennsylvania Canal Society, Field Trip to Lower Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. Trip will cover the Monocacy Aqueduct, Whites Ferry, Edwards Ferry, Lock 25, Seneca Aqueduct , Lock 24, Violettes Lock, Pennyfield Lock and a tour of the refurbished Great Falls Tavern Visitors Center. A ride on the mule drawn canal boat will be included in the trip. For information, contact Dave Johnson at 301-530-7473.

Oct 19, Sunday - 47th Annual Old Middlesex Canal Fall Walk. Our Fall Walk will include two watered sections of the Middlesex Canal in Woburn. We will meet at 1:30pm at the parking lot behind the Woburn Cinemas on Middlesex Canal Drive, off Route 38 just south of its intersection with Route 128 (Interstate 95) at Exit 35.

The walk will be conducted in two segments. The first will proceed south along the watered canal from the parking lot to Winn Street and return. After returning to our cars, we will drive to park again for the second segment, north of Route 128.

Leaving the Cinemas parking lot on Middlesex Canal Drive, take a left back onto Route 38 heading north. After passing under Route 128, take a right turn at the lights onto Alfred Street to the Baldwin mansion, a few hundred feet on the left. The second segment of the walk will proceed north from the parking lot behind the mansion, currently a Chinese restaurant.

For more information please call Roger Hagopian (781-861-7868) or e-mail Robert Winters <robert at middlesexcanal dot org>.

Oct 24-26 - CSNYS trip to the Cayuga-Seneca Canal. Michele Beilman, 315-730-4495; <mbeilman at twcny dot rr dot com>.

Oct 25 - Waterloo Heritage Day, Morris Canal, Stanhope, NJ; 11-4. 908-722-9556.

Oct 26, Sunday - Fall Meeting of the Middlesex Canal Association. Time: 2:30pm. Place: Middlesex Canal Museum, N. Billerica - Nolan Jones will present a slide tour of the canal route as it exists today. Refreshments and conversation will follow the lecture.

Directions to the Museum/Visitors Center: Telephone: 1-978-670-2740. From Rte 3 North or South: Take Rte 3 North or South to Exit 28 “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at a fork. After another ¾ mile, by a traffic light, cross straight over Route. Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road, which will put St. Andrew’s Church on your left. Go about ¼ mile; bear right, then turn right onto Faulkner Street. Go about ¼ mile; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the falls.

Nov 15 - Geology hike in the Point of Rocks area, C&O Canal. 703-723-6884 or <nancymadeoy at aol dot com>.

Nov 23 - Continuing hike series, 10:30 am, Goose Creek Navigation System, south of Leesburg, Va. Contact Pat White, 301-977-5628 or <hikemaster at candocanal dot org>.

Dec 13-14 - “Civil War Event 2008” will be held at the Savannah-Ogeechee Canal Museum & Nature Center in Savannah, Georgia. Activities will include a Civil War encampment and reenactment of events that took place at the Canal in 1864 during Sherman’s March to the Sea. There will be period craftsmen, tours of historic Locks 5 & 6, children’s activities and sales of food and gift items. Admission is $2 for adults, $1 for children 4-12. For more information, please call (912) 748-8068 or e-mail <info at savannahogeecheecanal dot com>.

Dec 31 & Jan 1 - New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day hikes along the C&O Canal. Details to be announced. Check the website, www.candocanal.org.

MIDDLESEX CANAL COMMISSION - SUMMARY REPORT

by Tom Raphael, Chairman

August 15, 2008

The nomination of the full route (including the overbuilt areas) of the canal to the National Register is currently waiting on the completion of a special version of the MAP BOOK bring prepared at the request of the Massachusetts Historical Commission. Features being added to the special version will coordinate the Nomination Narrative with the Area Data Survey Matrix. The first draft is being reviewed and when completed will allow the Nomination to be submitted to the National Park Service in Washington.

Unfortunately, the Phase I, Mill Pond/Canal Project in Billerica is delayed due to the uncertainty of ownership of the Cambridge Tool & Manufacturing Company, whose property was formerly that of the Middlesex Canal Company. and encompasses all of the project.

Phase II has been started and has produced a study of all of the approximate 12 mile of extant canal segments. There are 19 segments ranging from 700 ft to 6000 ft in length. Five segments have been rated high for restoration.

Woburn, Segment #5, Alfred to School Streets, has favorable City support and is progressing from Concept to 25% Design.

Wilmington Segment #6, Main Street to Burlington Avenue, and including the Ox Bow and Maple Meadow Aqueduct, has been presented to the Wilmington Town Community Development Technical Review (CDTR) and is awaiting their recommendation to the Selectmen.

The Commission is carrying all three projects along concurrently with the intention that the first to meet all the 25% Design criteria will be submitted to receive the Federal Highway Enhancement funds to proceed to 100% design and construction.

SPRING 2008 MCA-AMC CANAL WALK

by Roger Hagopian and Robert Winters

The Spring 2008 Canal Walk was held on Saturday, April 26th. As traditional, the walk was conducted jointly by the Middlesex Canal Association and the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Local Walks Committee.

Originating at the Wilmington Town Park, about 40-50 people participated. Walk leaders Robert Winters and Roger Hagopian led the assortment of AMC hikers, amateur historians, nature lovers, bird watchers, and fitness enthusiasts. The walk immediately proceeded along a dirt road which merged into the dry bed of the canal. Mary Stetson Clarke’s book - The Old Middlesex Canal - describes this location after rainstorms as still retaining the semblance of a waterway.

This is where the canal formed an ox-bow to avoid a swamp and swung back skirting a hill where a tell-tale boulder reveals the grooves from towropes grinding against it as the barges and packet boats were pulled around the sharp curve. As we passed that very hill a huge recessed section reminds us that stone and fill were quarried here for the construction of the Maple Meadow Brook Aqueduct.

Here also, long earthen embankments, still extant, were required to maintain the level of the canal high above the wetlands. Some of our walkers searched through the remnants of stone and boulders for holes and impressions created by drill bits, used for splitting stone.

The aqueduct employed a wooden trough and narrow towpath to carry canal boats about 10-15 feet above the stream. Trusses supporting the structure were anchored by recesses in the abutments and the central pier. Evidence of these recessed truss footings are visible near the base of one abutment.

Absent the trough and towpath, this brook had to be crossed on a temporary bridge, assembled earlier that day on an extension ladder, provided courtesy of Betty and Gerry Bigwood.

Continuing along the dry bed with banks rising 15-25 feet above the wetlands we crossed Butters Row, where the Wilmington monument of the Middlesex Canal Commission is located. Our walk concluded at Patches Pond, from which the extant canal emerges then disappears into a suburban neighborhood.

Although this walk is conducted every three years, each excursion was unique. New discoveries are made each and every time.

THE FUTURE OF OUR MUSEUM - ONE MEMBER’S VIEW

By Alan Seaburg

Our growing Endowment Fund is the key financial base for the future development of our Middlesex Canal Association’s Museum and Visitor’s Center here in North Billerica. It is also our best hope for its ability to maintain an expanding Permanent Exhibit Collection, to showcase from time to time Special Canal Exhibitions, and to provide a small working staff that will enable all this to take place over the coming decades.

At the present time we are fortunate to have space in the Faulkner Mill and to have the day to day operations of the Museum run by wonderful volunteers. These two facts have enabled the birth of our Museum. But to make it better serve our hopes and dreams we will, sooner than later, need much more exhibit space and a small paid staff of museum professionals to oversee the development and expansion of the educational opportunities that are inherent in our unique Museum.

Of course, the Museum will always need a large enthusiastic core of volunteers with all kinds of experience and knowledge to supplement and enrich the contributions of the permanent staff. And eventually it will also need its own special building, to be situated near the park the Middlesex Canal Commission plans to develop around the Mill Pond here at North Billerica. Fortunately there are two buildings adjacent to the Mill Pond that just might fulfill the needs of the Museum. But such a structure would require essential repairs and renovations - a cost factor that needs to be kept in mind and one that the Endowment Fund could only partially underwrite. Generous help from the on-going business and social community once served by the old canal would be a necessity for the proper building to become reality.

To attract visitors on a regular basis, new ones and those who return yearly, the Museum needs to have special exhibits as appropriate on various canal subjects. One of these will certainly be about the inns and taverns that existed or grew up alongside the canal route to wet the whistle of those canalling, provide them with hearty meals and when needed a bed for an overnight stay. Another will exhibit the various goods and manufacturing items shipped via the canal to the port of Boston or to the several towns along the route. Medford, for example, utilized the canal to obtain fine timber from New Hampshire for its ship building yards while Chelmsford used the canal to convey granite blocks from its quarry to Charlestown for the State prison being built there and to Boston for its new South Meeting House.

A third special exhibit would focus on the kinds of boats and other craft that traveled the canal. Indeed, it would be excellent if the Museum could have a replica of a packet boat for visitors - especially the youngest - to climb and explore such as exists at the London Canal Museum. Other shows could focus on canal art and artists, the social history of canal life, working animals connected with the canal, and lively histories about the towns and cities the canal served. The possibilities are rather endless. Always the Museum should have activities designed for the children who visit with their parents and families.

While the Middlesex Canal will always be the Museum’s chief focus - it can also serve as a showplace for the entire network of canals and waterways of New England. This would in time increase our membership from just a local canal group to being in some ways a canal museum, which served in part as a regional canal museum for New England. One of the by-products of this would be to increase the readership of Towpath Topics thereby allowing the magazine to include articles now out of its more limited scope. As a result, its usefulness as an educational tool would simply blossom in value.

We need to keep in mind too that our programs could expand from just MCA walks to visits to other canals in New England. Indeed, the Museum could sponsor for our members and their friends visits to related museums such as those dealing with all forms of transportation in New England including trains, bikes, and even ocean going ships. A further extension would be to investigate museums devoted to the history of New England’s business endeavors. And finally with more members and funds available we could greatly increase our educational programs for local schools - those served directly by the Middlesex Canal and also for schools in the wider canal region.

We have with our Museum and Endowment Fund a firm hold of a great dream that I believe can and will be built into reality over the decades ahead. But keep in mind that this is but one member’s view - others will have just as exciting and wonderful hopes and ideas. As a member of the Association I hope you will share yours with all of us for the seedbed of the best lies in collective sharing, effort, and dreaming.

Letters, First Published in the Boston Daily Advertiser

(1818), in Answer to Certain Questions, relative to the Middlesex Canal

by John Sullivan, Agent of the Corporation

[The letter was researched, typed and contributed by MCA

BoD member Howard Winkler

from an electronic facsimile found at the Tisch Library, Tufts University.]

Mr. Hale - Having been called upon through the medium of your paper for some elucidation of the affairs of the Middlesex Canal, in its relation especially to the public, I avail myself of the opportunity, of making known to the community on whose commercial prosperity it was originally calculated to have a beneficial influence, something more of its history than is commonly known. And deeming it necessary to go back to its origin to trace it through its progress - to shew the magnitude and difficulty of the enterprise, I hope, in this day of research into the resources of our country, it will be a useful, if not an entertaining inquiry.

Communication by water between distant parts of the interior having in every country been found beneficial - it was natural that the capability if our own, should have engaged the attention of men of comprehensive minds, and patriotic feelings. The person to whom the origin of this enterprise is attributable, whose virtues and talents were honored by the highest confidence of the state, was early in life acquainted with the extensive and improving districts of New Hampshire and Vermont, towards which the canal now leads; and when he became a citizen of Boston, the reciprocal benefits of concentrating their trade here, and of procuring them a great market for the natural growth of the soil, and the products of industry, was perceived, and became a favorite object of his exertions; seconded by a number of gentlemen of great enterprise, wealth and public spirit.

It was in 1793 that the first act incorporating James Sullivan, Esq. and others, by the name of the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal, was passed.

The object of this undertaking will be at once comprehended by observing on a map of New Hampshire the course of Merrimack river, which rising in the Winnipisioke Lakes, pursues a direct course towards this metropolis, till within 27 miles of our harbor; when it suddenly bends to the northeast, and in the distance of forty five miles passing numerous falls, it reaches Newburyport.

The County of Middlesex, in a line from this bend of the river to Charlestown, is uncommonly level and well supplied with streams; and Concord River, running from Sudbury through Billerica, afforded the source from which a canal might be fed.

Rafting had long practiced in the Spring and Autumn to Newbury-and there was reason to expect business of every kind would conform to this new and accommodating rout to a greater mart.

After giving a succinct description of the principal features of the acts and of the works, and the difficulties surmounted, by the perseverance of the Proprietors, I purpose to speak of the system of management, business and prospects of the Canal.

The proprietors did not proceed without due precaution. The first act of Incorporation appears to have been framed by legal precision as well as to protect the private rights, as to guard the proprietors against extortion. - They might appropriate land, but were to pay damages. If the sum tendered was not acceptable, an application to the Court of Sessions for a committee to appraise them was allowed; and the cost fell on the unreasonable party. - Treble damages done the Canal are recoverable, and offenders liable to indictment, imprisonment and fine - It is a perpetuity; its tolls unalterable by law; and it is an exclusive privilege as to the county; and Concord river for twenty miles is granted as an appendage, subject to the same tolls.

Col. Baldwin was sent to the Southward to get information, and view other canals then commenced under Washington’s patronage.

Mr. Weston a celebrated English Engineer, was invited from Philadelphia, to survey different routs, attended by Judge Winthrop and some other gentlemen. His report, with his estimates on record, giving the outlines of the work. He pronounced the country remarkably favorable-and estimated the cost at 100,000l sterling. The streams were found to run across the course of the canal. A short description of the country will not perhaps be found tedious, and seems necessary in this place.

The Merrimack in Chelmsford is about four hundred yards wide. The southern bank is for some distance back, intervale land, from which it rises abruptly 20 feet to a plain. Thence to Concord river in Billerica it is very level land for five miles, except that the rout crosses in this distance a small river and some meadows about ten feet lower than the surface of the canal, -which is carried over them by embankments. At Merrimack river there are three stone locks, the lowest of which is placed in an excavation or basin, below low watermark, which was very difficult to accomplish. Both shores of Concord river were found to be ledge. The canal penetrates them, passes across, a little above a mill dam, which the Corporation purchased and erected mills upon. On leaving Concord river the canal is carried twenty feet deep for a mile, much of the excavation being in rock. Then a level of five miles is preserved. Crossing Shawsheen river by an Aqueduct 130 feet in length and about 30 feet high, with extensive embankments from each end to the higher ground. -Thus continuing South Eastward, several successive levels are formed. That of Wilmington is six miles, and passes over extensive meadows, in one of which the Banks sunk more than 60 feet, till finally the canal stands firm above the morass- in some instances 25 feet, for long distances. It passes through hills and ledges - over seven rivers - descend from Concord river in all with 20 locks above an hundred feet perpendicular measurement.

It is not easy without too much detail for this medium of communication to give an adequate idea of the toil, the board of directors endured in very frequent personal attendance on the line during ten years. - They did not meet with a sincere co-operation from the inhabitants, who were undoubtedly to be benefitted by their proximity to the work. But for most part a difficulty of settlement was met with-many controversies arose, and the liberality and equity of the corporation did not infrequently meet an ungrateful return.

The excavation and embankments were done very often by contracts, by the rod in the length of the canal, and varying in price according to its depth and width.

Many laborers were employed by the month, their wages were 8 dollars - Carpenters 10 to 12, at that period.

The locks and aqueducts were erected of wood, supported by stone. The directors calculating that the saving in the first cost, compared to the cost of stone work would warrant the periodical renewal of them; being but a small part of the whole expense of the canal.

It was first intended to come into Medford Ponds, but it was finally determined to continue the canal seven miles further to Charlestown, which thou’ increasing the expense, will prove to have been best. The whole amounts of assessments, to the time the work reached the tide water was 520,000. The assessment had been paid at the rate of 5 or 10 dollars a share per month. This includes some valuable purchases of real estate.

The variation or extension from the first plan caused the cost to exceed the first estimates; and perhaps controversies had not been expected in many instances. There was difficulty from the leakage on the first filling the canal. Breaches took place, and damage to a considerable amount ensued, not uncommon in new works of this kind that are incautiously filled. It was a great effort especially at that period for a private company-especially as the science and principles of canalling were not experimentally known here. But no great mistakes were made - and the ingenuity of the superintendent, Col Baldwin, guided by the judgment and indefatigable attention of the committee of operations would have terminated in complete and early success, but for causes not inherent in the undertaking, that I shall next mention.

J. L. Sullivan

William Weston and his Contribution to Early American

Engineering

by Richard Shelton Kirby, Member -- Read at the Engineers’ Club, New York, and

at the Iron and Steel Institute, London, April 22nd, 1936

[This article researched and contributed by MCA BoD member Howard Winkler.]

Early in the last decade of the eighteenth century a wave of enthusiasm for better means of communication swept over the United States. The new country was beginning to find itself, to plan vaguely for a closer physical and political coherence. But a far stronger urge, economic and localised, was evidenced by the almost frantic eagerness of the leading commercial centers to secure, each for itself, new trade routes to the west, to reach out toward the fertile lands across the Appalachians. Especially did the longer river valleys invite canals, such as were then being built all over the mother country.

President Washington was a guiding spirit in three canal projects in his native state. Other canal projects were begun in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania. But it was not long before their enthusiastic projectors realized that they could not proceed with confidence without the guidance of trained civil engineers. And there were in the country practically none.1 True there were surveyors like Andrew Ellicott and Simeon De Witt; forward-looking mechanics like James Rumsey; inventive mechanical geniuses like Oliver Evans; scientific men like David Rittenhouse; practical men of affairs like Loammi Baldwin and Philip Schuyler, and former engineer officers of the Continental Army like Thomas Machin.2 But none of these men knew much about canal locks or turnpike roads.

Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation

The Pennsylvania group, led by Robert Morris, was the first to send abroad for a

trained engineer. Early in 1792 one of the group wrote Patrick Colquhoun, a

Scottish-born London magistrate and scholar, who had lived in Virginia as a

youth, asking him to find them an engineer who could design and build canals and

turnpike roads. After trying to get one Dadford, he finally secured William

Weston, the subject of this sketch, who, it seems probable, was then engaged in

building canals in Ireland.

William Weston was born, probably at or near Oxford, in 1753. His early training may have been begun under James Brindley, who died, however, when Weston was only nineteen. Weston doubtless served under other engineers, on canals in central England. The only English work of his of which we have certain knowledge is the three-span stone arch bridge over the River Trent at Gainsborough, built during the years 1787-91. A view of the bridge, drawn by Weston himself, appears in Adam Stark’s The History and Antiquities of Gainsburgh (2nd ed. 1843). In connection with the bridge there was a turnpike road.

In 1792 Weston agreed with Colquhoun, who was acting as London representative of the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company of Pennsylvania, to come to America and serve as engineer and superintendent of two related canal projects which had already been begun. This company was expecting to build a canal to connect the Susquehanna below Harrisburg with the Schuylkill at Reading, while an affiliated company, the Schuylkill and Delaware, expected to canalize the Schuylkill down to Philadelphia. The leader in the combined undertakings was Robert Morris, intimate friend of Washington and one of the ablest men in the public life of his day.

Just how Weston came to be chosen and invited is something of a mystery. Perhaps Benjamin Franklin was the first to suggest the importation of a British engineer, for he had written from London in 1772 to Samuel Rhoads, later Mayor of Philadelphia:

“I think it would be saving money to engage at a handsome Salary an Engineer from here who has been accustomed to such Business. The many canals on foot here under different great Masters, are daily raising a number of Pupils in the Art, some of whom may want Employment hereafter, and a single Mistake thro’ Inexperience in such important Works, may cost much more than the Expense of Salary to an ingenious young man already well acquainted with both Principles and Practice. This the Irish have learnt at a dear rate in the first Attempt of their Great Canal, and are now endeavoring to get Smeaton to come and rectify their Errors.”

Or perhaps James Brindley the younger, who was in this country as early as 1785, may have suggested Weston to the authorities. A reputation as the foremost engineer in Europe (which he certainly was not) seems to have preceded Weston. The following are extracts from the formidable contract of nearly 2,000 words signed by Weston, Nov. 5, 1792. Weston was then of Oxford.

“The said William Weston doth hereby covenant and agree that he will take his passage in the Packet for New York or Philadelphia and on his arrival take upon himself the management, superintendence and direction of an inland navigation in the State of Pennsylvania, further covenants and agrees that being furnished with the usual assistance which Engineers receive he will take the necessary levels, direct the surveys and execute and furnish proper plans and sections and will devote so much of his attention to the said undertaking not exceeding more than seven months in any one year for the space of five years In case the canal is completed before the end of five years Weston shall be at the disposal of the said Robert Morris with power to direct Weston to any other object of improvement in his professional line in the States of Pennsylvania or New York. Provided always that the salary hereinafter mentioned shall not be disturbed or diminished (sickness or absolute disqualification by imbecility or otherways excepted).”

“in consideration of the above mentioned stipulations the said committee will allow the sum of eight hundred pounds sterling money of Great Britain yearly and each year commencing from and after his departure from England the said departure to be ascertained by a certificate signed by the commander or chief officer of the ship in which he shall take his passage. Provided always that the said salary shall be paid to the said William Weston no longer than he shall continue to execute his professional duties it being always understood that in the event of continued bad health, bad habits or any unconquerable malady or any other imbecility or weakness either of body or mind which may render the said William Weston incapable of executing his duties with propriety and effect for the space of seven months together the salary shall be no longer payable.”

The minute book containing a copy of the original contract is in possession of the Reading Company, Philadelphia. This railroad secured control of the canal in 1891.

Weston sailed on the Carteret packet from Falmouth, November 23, 1792, for New York; his salary began the day he sailed.

Up to the time that Weston arrived in the United States, there were no canals worthy of the name here. Two narrow and shallow canal ditches were being dug, the two-mile Carondolet canal at New Orleans and the equally tiny but longer Dismal Swamp Canal which was to connect Norfolk with Albemarle Sound. More interesting was the short South Hadley Canal, with its inclined plane up which boats were to be hauled by cables. All three of these projects came into use, in part, during 1794. One should perhaps mention also the “Patomack” locks and the James River Canal, although neither of these was progressing satisfactorily. The Santee Canal in South Carolina had been chartered, but construction work had not yet commenced.

It is interesting to note also that, at the time of Weston’s coming, while surveyors’ compasses were common in the States, engineers’ levels were almost, if not quite, non-existent. (David Rittenhouse doubtless could have made one, but it is quite certain that he had not). In fact Weston may have brought with him the first leveling instrument used on this side of the Atlantic. It was, according to Weston’s own description, a Y-level with achromatic glasses, and had been made for him by Mr. Troughton, mathematical instrument maker of Fleet Street, London.3

Weston arrived in Philadelphia, via New York, early in January, 1793, and reported at a meeting of The President and Managers of the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company on January 14. The Board almost immediately endeavored to alter their contract with him, to the end that he should be “at the entire disposal of the Company for the said five years to be employed at any place or places within the States of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and Delaware,” at a salary of £1,500 per annum. It is not clear whether such a change was made in the actual contract. Neither is it clear whether or not Weston at this time served the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company, although this company was very anxious to borrow his services almost as soon as he arrived.

Weston seems to have begun work in the field early in February, for it was reported to the Board “that he hath taken measures for sending up a level by the Harrisburg stage.” The committee also reported “… that it is impossible at present to say what time it may require before Mr. Weston can determine on the propriety of the work at present performing by the labourers.”

The original scheme contemplated building a canal up the Schuylkill valley to Norristown, and improving the river from there to Reading; while from Reading a canal was to extend to the Susquehanna, via Lebanon. Weston early convinced the company of the folly of attempting to improve the Schuylkill, advising rather a canal the whole distance of about 82 miles.

Work had already begun before Weston arrived, apparently under the direction either of Doctor William Smith,4 one of the managers of the company, or of David Rittenhouse, for we read in An Historical Account of the Rise, Progress and Present State of the Canal Navigation in Pennsylvania, 1795: “He found more than six hundred men at work, viz. upwards of two hundred at Norristown and about four hundred at the summit or middle ground, between Lebanon and Myerstown.”

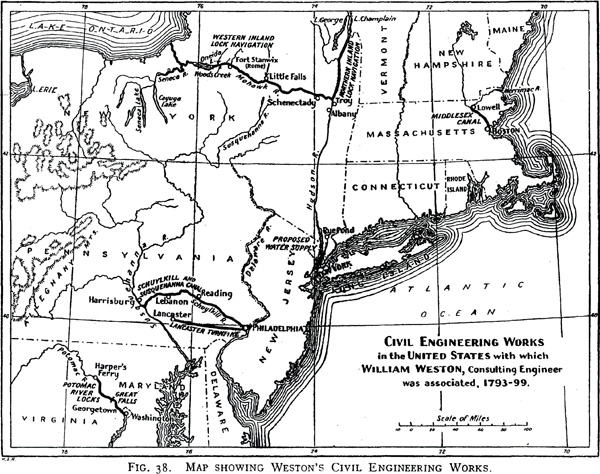

After his examination of the work, Weston made his first report, in which he suggested slight changes in dimensions and hinted that the canal might serve also to supply Philadelphia with water. In Weston’s capacity as engineer and superintendent he was obliged to hire labourers and even to supervise the manufacture of the bricks for the locks. How long Weston continued with this canal company is not certainly known. Probably about two years, for we have his report to the company for 1794 (written from Lebanon, Dec. 16), from which it is easy to infer that the financial condition of the company was fast becoming precarious.5 After he left it suspended operations. Work was resumed in 1811 by its successor the Union Canal. The canal finally completed about 1826 under Canvass White was a smaller affair than Weston had originally planned. Very soon, even though means of communication here were slow, Weston’s Fame had spread; it was realized that the canal company in Pennsylvania had a real engineer and that their work was doubtless therefore progressing along the most approved lines. During his stay in the United States he served as engineer or consultant on six canals, a turnpike road, a public water supply and a bridge (see Fig. 38 above). In other words he was associated with practically all of our earliest engineering construction projects of any importance. The projects overlap somewhat chronologically; the first has already been described, while the others will now be noted somewhat in chronological sequence.

Middlesex Canal

At the urgent request of Loammi Baldwin (the elder), Weston stole away from

Philadelphia in the summer of 1794 to survey and level the Middlesex Canal in

Massachusetts. One of its chief financial backers, a competent executive with

much native engineering ability, who had begun the project almost single-handed,

had made a special trip to urge Weston to come up. He found him engaged, he

said, on the two canals and the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike. Weston was

then apparently on a full-time basis at £1,500 per annum. Permission was

obtained from the Schuylkill and Susquehanna authorities and Weston left

Philadelphia early in the summer and spent several weeks during July and August

in laying out the Middlesex Canal, connecting the Merrimack River near the

present site of Lowell, with tide water at Boston, some twenty-seven miles. For

this he received nearly $2200, apparently, and he certainly earned this money,

for before he came up the directors had depended on a survey made by one Samuel

Thompson of Woburn, according to which the canal would have to ascend 16½ feet

between the Concord River at Billerica and the Merrimack. Weston found that

instead it must descend nearly 25 feet; the first leveling was therefore some 41

feet in error in a matter of 5 miles. And there was incidentally an error of 35

feet on the Charlestown end, which was perhaps not quite so serious, for

everyone knew that Boston was lower than Billerica.

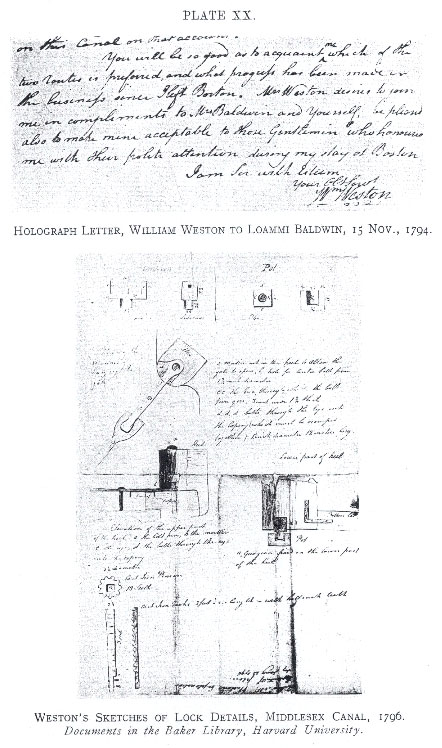

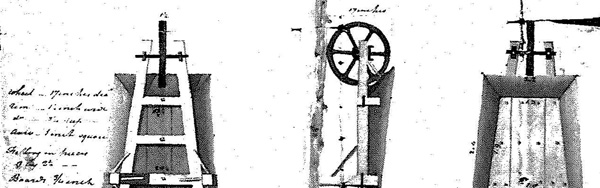

Weston continued his contract with the Middlesex Canal proprietors for some years after he made his original survey in 1794. A number of letters from him to Loammi Baldwin are extant.6 (See Plate XX, above). Apparently the latter wrote to his friend Weston for advice whenever a new problem arose, and Weston replied sometimes from Philadelphia (where his permanent address seems to have been c/o Richard Welles, Esq., North Third Street); sometimes from Lebanon, Pa., and later (1796 and 1797) from Fort Stanwix (now Rome), N.Y. The letters have to do with canal and lock cross-sections, with the troublesome question of watertight masonry walls and with gate-operating mechanism.

The proprietors in 1798, sent to John Rennie, in Edinburgh, certain plans of Weston’s for the extension of the Middlesex Canal up the valley of the Merrimack, asking for his advice. He returned them in September of that year with a letter in which he avoided committing himself, because, he said, the information was insufficient.

Transcribed text of the letter in the plate, above.

Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike

How much Weston had to do with the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, the

first of any importance in the United States, is problematical. The company was

incorporated in 1792, with the aged astronomer David Rittenhouse, who was

interested in the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal, as one of its first “managers”

or directors. Rittenhouse apparently had had general charge of the original

surveys. The 62-mile road was already, then, well under way when Weston arrived,

although I have thus far not been able to find that any engineer except

Rittenhouse was in charge. Loammi Baldwin, on his visit to Philadelphia in 1794,

when the turnpike was nearing completion, wrote of Weston’s connection with it

“tho this is not directly in his profession, yet he appears competent to the

undertaking.”

Potomac River Locks

In the latter part of 1794 President Washington seems to have had some

interviews with Weston concerning the improvement of the Potomac River above the

site of the projected federal city. The “Patomack Company” had been

incorporated in 1785, with Washington as its president. James Rumsey

(1743-1792), better known for his not too successful attempts at steam

navigation, was at first superintendent of construction. The company aimed at

canalization of the river from Harpers Ferry to Georgetown, some sixty miles. In

all there were five rapids or falls to overcome, of which the most serious were

the Great Falls, ten miles above Georgetown, where the river drops seventy-six

feet nine inches in twelve hundred yards, and then passes through towering

perpendicular cliffs. The canal, still traceable, passed around the falls with a

series of five locks.

The locks at the Great Falls presented the greatest challenge to the skill of the promoters and Washington was anxious to secure the best advice possible as to their location and construction. In all probability he had never seen canal locks, and was not unwilling to listen to those who advocated alternative means, such as inclined planes. It is quite possible that Weston showed Washington a model of canal locks in Philadelphia. At any rate Weston came to the Great Falls in March, 1795, and made an examination and report of the work then in progress there. He seems to have commended the layout and to have made a particularly favorable impression on Washington, a supremely good judge of, men, for in the President’s letters are frequent complimentary references to Weston’s skill and judgment.

Apparently James Brindley, a son or nephew of the builder of the Bridgewater Canal, had given his advice previously, in fact as early as 1786. Brindley had also some connection with the Pennsylvania Canals. And there were other engineers, or men who posed as such, anxious to give advice to the Patomack Company, for Washington wrote in 1795 to his secretary, Tobias Lear, who was then president of the company: “Mr. Claiborne’s Engineers [for it seems he has two for different purposes] are fixed in this City; either of which according to the use for which you want one might be had at any time; but as I am not strongly impressed with a belief that men of eminence would come to this Country in the manner and under the circumstances they have done (but this I say without having any knowledge of the real characters of these Gentlemen - and without desire to injure them) might it not be politic to obtain the opinion of the most competent of them, before Mr. Weston (who is known to be a scientific and experienced engineer) gives his? He will not adopt their opinions contrary to his experience and judgment; but if his opinion is first taken, and transpires, it may be given into by them, from the want of these in themselves, endeavoring thereby to erect a character on his foundation.”

Who these so-called engineers were is problematical. Perhaps they were young men, and French. May they not have been Marc I. Brunei, then a precocious young man of 25, and his friend Pharoux.

Weston seems to have received for his visit a fee of £370 sterling. He made at least one other visit, professional or otherwise, to the Great Falls, for he wrote Loammi Baldwin in April, 1796, that he had just returned from Virginia. The Patomack Company’s affairs did not prosper after Washington’s death. Its charter was from time to time renewed and eventually the works became part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which reached out toward the Ohio, but never got beyond Cumberland, Md.

Western Inland Lock Navigation Company

As early as April, 1793, Weston’s fame had spread to New York State, for

Philip Schuyler wrote from Albany to Robert Morris7 asking the

Schuylkill and Susquehanna people to loan him and promising that he would not be

detained longer than necessary to make surveys and give directions on the

canalization work then being pushed in the Mohawk Valley and westward, in the

effort to connect Albany, or at least Schenectady, by way of the Mohawk River,

with Oneida Lake, and the latter with Seneca and Cayuga Lakes and also with Lake

Ontario. The letter apparently did not bear fruit for some two years and the

company proceeded temporarily without Weston. In the spring of 1795 Weston made

an extensive examination of the New York State project8 and made his

first formal report to the directors of the Western Inland Lock Navigation

Company, which, together with the Northern Inland Lock Navigation Company had

been incorporated three years earlier. More than a year after his first visit,

that is in 1797, he seems to have left Philadelphia and assumed charge of this

work, with several local surveyors more or less under him, among them Benjamin

Wright, who eventually became chief engineer of the Erie Canal. Apparently he

spent parts of two years in this region, making his headquarters at Fort Stanwix,

(now Rome). During this time he built, or rather rebuilt, the elaborate masonry

locks at Little Falls.

The Lock Navigation Company was only moderately successful in what it attempted, for the western country was developing so rapidly that men’s ideas were constantly enlarging. In 1798 the Erie Canal was only a dream in the minds of a few visionaries. By 1812 it had taken such form that the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company was taken over by the State and surveys for the Erie Canal began. By 1811 the surveys were apparently complete9 and were sent over to Weston, who although residing in England, seems to have been considered here as a sort of consulting engineer in perpetuity. He wrote the Erie Canal Commissioners at this time: “Should your noble but stupendous plan of uniting Lake Erie with the Hudson, be carried into effect, you have to fear no rivalry. The commerce of the immense extent of country, bordering on the upper lakes, is yours forever, and to such an incalculable amount as would baffle all conjecture to conceive. Its execution would confer immortal honour on the projectors and supporters, and would in its eventual consequences, render New-York the greatest commercial emporium in the world, with perhaps the exception at some distant day of New-Orleans, or some other depot at the mouth of the majestic Mississippi. From your perspicuous topographical description and neat plan and profile of the route of the contemplated canal, I entertain little doubt of the practicability of the measure.”

One of the best informed, not to say patriotic, of the early writers on the Erie Canal observed that: “In 1813 the commissioners entered into correspondence with an American gentleman at that time in London, authorizing him to engage William Weston, Esq., then considered the most accomplished engineer in Europe, to come over and survey the route of the canal and proposed as a maximum salary seven thousand dollars per year. Fortunately Mr. Weston’s engagements were such that he thought proper to decline. . . It may be considered a fortunate circumstance that Mr. Weston did not accept the offer of the canal commissioners.10 Because from the ostentation usually displayed by foreign engineers and the great expense attending their movements the people of this frugal and republican country would have been discouraged, and it is more than probable the work would have been abandoned or at least indefinitely deferred.” 11

Schuylkill River Bridge

In 1798 or 1799 Weston played an important part in designing the piers of the

monumental “Permanent Bridge” spanning the Schuylkill at Market Street,

Philadelphia. The superstructure consisted of three covered wooden trusses,

designed and erected by the carpenter-engineer Timothy Palmer of Newburyport,

Mass.

Of its two piers, the westerly one gave especial trouble, for the water was deep and bedrock was more than 41 feet below its surface. Weston had designed the piers, it would seem, before he left for England. In fact he had at first furnished plans for a stone arch bridge and later had planned a cast-iron structure. The following extract is from Richard Peters’ A Statistical Account of the Schuylkill Permanent Bridge.12 “The general Wish of the Stockholders, at the Commencement of the Project, was strongly in Favour of a Stone Bridge. A Draft of a Stone structure, elegant, plain, practicable and adapted to the Site, with very minute and important Instructions for its Execution, was furnished to the President gratuitously, by William Weston, Esq. of Gainsborough in England; a very able and scientific Hydraulic Engineer, who was then here, and from friendly and disinterested Motives, most liberally contributed his professional Knowledge and Information to promote the Success of the Company. The Foundations of the present Piers and abutments were laid nearly according to his Plan, tho’ the Circumstances compelled a considerable departure from it, as the work advanced. His communications were attended to with great advantage, wheresoever they could be applied. Having viewed the Inefficiency of the Eastern Coffer-Dam, in the same spirit of Liberality he furnished to the President a Draft for the western Coffer-Dam, before his Departure for England. This plan was original and calculated for the Spot on which it was to be placed. It was faithfully and exactly executed under the Care of Mr. Samuel Robinson, who was then Superintendant of the Company’s Work in Wood. Mr. Weston foresaw great Risques and Difficulties arising from the peculiar character of the River, and the Nature of its Bottom, in so great a Depth of Water. He declared that he should hesitate to risque his professional Character on the Event, tho’ he was convinced that the whole Success of the Enterprise depended upon, and required, the Attempt. Some Idea of the Magnitude may be formed, when it is known that 800,000 Feet (Board Measure) of timber were employed in its execution and the accommodations attached to it, Sufficient in Quantities for a Ship of the Line.”

But it was soon discovered that the expense of erecting a stone bridge, would far exceed any sum, the revenue likely to be produced would justify. For this reason alone, no farther progress was made in the stone bridge plan. And though some other drafts, among them a very elegant one by Mr. Latrobe13 were presented, the board of Directors were under the necessity of returning them, as being objects, however desirable, too expensive to be executed with private funds. It was therefore concluded to procure plans of a bridge, to be composed of stone piers and abutments, and a superstructure of either wood or iron. Mr. Weston, at the request of the President and Directors, sent from England (after viewing most of the celebrated bridges there, and adding great Improvements of his own), a draft of an iron superstructure, in a very superior stile; yet with his usual attention to utility, strength and economy, accompanied by models and instructions. Although highly approved it was not deemed prudent to attempt its execution. All our workmen here, are unacquainted with such operations; and it was thought too hazardous to risque the first experiment. “The castings can be done cheaper here, than in England, and with metal of a better quality, though the amount of the erection would in the whole, far exceed one of wood. Mr. Weston’s draft14 is preserved, and may yet be executed in some part of the United States; and it would do honour to those who could accomplish it.”

The building committee of the bridge reported on December 31, 1802: “Our particular duty, as a committee, was to superintend the execution of the plan. But as members of the board, we cannot avoid lamenting that the dangerous character of the river, its extraordinary depth and rocky bottom, forbad any other mode, to ensure the stability of the piers, than that which necessity compelled us to take. Every substitute we could devise, or were informed of, even though some were only plausible, or palpably visionary, were stated to Mr. Weston, more competent to judge. He decidedly advised us to the mode we have adopted; warning us of the difficulties we had to encounter. He disinterestedly gave instructions, and furnished the plan of the coffer dam, which is a pattern worthy the imitation of all who engage in such enterprises.”

Weston wrote from Gainsborough, England, to Peters on May 4, 1803, his enthusiastic congratulations on the completion of the western pier: “I most sincerely rejoice at the final success that has crowned your persevering efforts, in the erection of the western pier; it will accord you matter of well founded triumph, when I tell you, that you have accomplished an undertaking unrivaled by anything of the kind that Europe can boast of. I have never in the course of my experience, or reading, heard of a pier founded in such a depth of water, on an irregular rock, affording little or no support to the piles. That the work should be expensive - expensive beyond your ideas - I had no doubt; the amount thereof, with all the advantages derived from experience, I could not pretend to determine; and if known, would only have tended to produce hesitation arid irresolution in a business, where nothing but the most determined, unceasing perseverance, could enable you to succeed. However, now ‘all your toils and dangers o’er’ I heartily congratulate you on the result: not doubting but the completion will prove as honourable to you as beneficial to the stockholders.”

The “Permanent Bridge” no longer spans the Schuylkill. Connecting as it did with the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, it served well, however, for some fifty years, when it was considerably altered; in 1875 it was burned down.

New York City Water Supply

Apparently Weston’s last engagement in America before he returned to England

was an examination and report on New York City’s water supply. The city of

some 50,000 persons, occupying a square mile of area at the tip of Manhattan

Island, was altogether dependent on wells for its water. And the city fathers

were in a quandary whether to use the Collect Pond (near the present Canal

Street) as many people urged, or to look elsewhere. In December, 1798, the City

Council voted to send for Weston and get his advice. He arrived about Feb. 1,

1799, and proceeded to make an investigation. His “Report on the

Practicability of Introducing the Water of the River Bronx into the City of New

York” was presented to the Council on March 16 and ordered to be printed. On

April 22 he was paid $799.67 for “Services and Expences. . . .”

This report of Weston’s is worthy of more than passing notice. After very properly disposing of the Collect Pond as a source of supply he proposes that the city tap the Bronx River just above Lorrillard’s Snuff Mill,15 about half a mile upstream from the little village of West Farms, then in Westchester County. He proposed to equalize the flow in the Bronx by raising the level of its principal source, Rye Pond, six feet. He would also build a six-foot dam near the Snuff Mill, and bring the water in an open conduit some 14 miles to a reservoir in or near the Park (City Hall Park). The total fall would be only 23 feet. For crossing the Harlem Valley he suggested 24-inch cast-iron pipe. No cast-iron mains had previously been used in this country,16 and very few abroad. In the Park Weston planned a “grand reservoir” of three compartments, for reception, filtration, and distribution respectively; the third one covered. In this he was far in advance of European practice. He expected his system to supply three million gallons daily by means of a dual distribution system. Any surplus was to be used for dry docks.

It is only proper to add that the suggestion that the city should use water from the Bronx was made to the city fathers by Doctor Joseph Brown in 1798, and that Weston, called in as an expert, adviser, elaborated on Brown’s scheme. Weston’s recommendations were not accepted. The first outside water came from the Croton River forty years later. Rye Pond, mentioned in his report and now part of Kensico Lake, has furnished a small fraction of the city’s supply since about 1884.

Conclusion

When Weston returned to England is not certainly known, probably in 1799 or

perhaps in 1800. His later career there is equally obscure. He was living in

Gainsborough in 1811, and when he died is not certainly known, possibly in 1833.

Some of his descendants are living near the ancestral home in Oxford.

One could quote almost indefinitely from comments on Weston’s ability made by those who came in contact with him in America. Apparently he easily inspired confidence in his skill. His reports indicate that this confidence was not misplaced, for they show a judicial temperament, careful analysis and excellent powers of expression. Without doubt he had a considerable influence on American engineering, and was a source of inspiration to the young canal engineers who were just reaching maturity during the years he was active in this country, such men as Benjamin Wright, James Geddes and Nathan S. Roberts, to name only three.

Among the writings of the men in public life to whom Weston was responsible I have found nothing but praise for his work. Only one word of criticism appears in a letter of De Witt Clinton, written in 1821 under the pseudonym of “Tacitus.” Clinton, while he praised Weston, made the comment that he was totally ignorant of the country and the people, that he had at one point at least on the Western canal involved the company in great expense by some unnecessarily heavy construction, and that he had neglected to make use of the local stone quarries. Unfortunately, Weston probably never had opportunity to present his side of the case. He planned and built substantially, as the English always have. Furthermore, it doubtless is true that Weston and the proprietors of these early canals did not always give sufficient consideration to sound economics, and did not realize the impending competition from turnpikes.

I feel that I should add here the long list of those persons on both sides of the Atlantic, who, during the past four years, have contributed bits of information or suggested leads which I have followed; space forbids, but I must mention my friend, Mr. H. W. Dickinson, of this Society; Messrs. Clark Dillenbeck and Gordon Chambers, officials of the Reading Railroad; Miss Edna J. Jacobsen, of the New York State Library, and the officials of the Baker Library, Harvard University.

The paper was illustrated by a map of the United States, showing the works cited in the paper, and by photographs of sketches and letters of Weston. From these Fig. 38 and Plate XX have been made.

Some Source Material on William Weston

Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation

Middlesex Canal

New York State Canals

Potomac River Locks

Permanent Bridge

New York City Water Supply

Discussion

MR. REX WAILES suggested that the fact that nothing definite was heard of Weston

after his return from America would be explained if he had retired from the

profession. He might well have done so, having regard to the salary he had

received in America.

MR. F. O. BECKETT observed that, judging by the illustration and his personal knowledge of the place, Weston’s bridge at Gainsborough was still in existence.

A VISITOR, referring to the New York water supply surplus that was to be used for dry docks, said that this plan was followed at Sebastopol, but he could not recall any other dock that was designed to be filled in that way.

MR. DlCKINSON, in reply to questions, said that the author had been unable to find either the date of the birth or of the death of Weston. The William Weston who died in 1833, judging by his will at Somerset House, was not our William Weston. The name was not uncommon.

Correspondence

MR. DlCKINSON wrote that Weston’s death must have occurred about 1833, because

Adam Stark, writing in 1842, states that he died “about nine years ago.”

Weston’s marriage (or second marriage) took place in 1792, to judge by the

following: “At Gainsborough co. Lincoln, Mr. Wm. Weston, engineer, to Miss

Charlotte Whitehouse, dau. of Mr. Whitehouse, an eminent brewer.” 17

Stark, however, says his wife’s name was Nettleship, presumably a previous

marriage. Weston sailed for America shortly after this marriage with Miss

Whitehouse and she it was, presumably, who was with him there as shown by the

letter on Plate XX.

SIR ALEXANDER GIBB made the interesting suggestion that Weston, after returning to England, might have engaged in contracting. There was a firm of Weston and Fletcher, contractors on the Ellesmere Canal, who in 1805 were granted a certificate of £32,670 5s. 5d. for work done; a sum which in those days it took a considerable amount of work to reach.

Footnotes:

1. However there were Christopher Colles of New York and John Christian Senf of South Carolina, neither of whom seems to have commanded the confidence of many of the leading men of the day. One should mention also L’Enfant and Marc I. Brunei. The elder Latrobe, primarily an architect, came to America a little later.

2. Machin was English-born and had worked as a young man under Brindley on the Bridgewater Canal. So perhaps had the younger James Brindley.

3. Letter from Loammi Baldwin to James Scott, June, 1794. Baker Library, Harvard University. Lorin L. Dame in a paper on the Canal (Old Residents’ Hist. Assoc., Lowell, Vol. III, 1884) quotes someone who describes the instrument as one made by S. and W. Jones of London.

4. Who was in charge of the school which later became the University of Pennsylvania.

5. The minutes of Apr. 25, 1796 record what appears like a formal release, with, payment : salary and interest to date, from, the Delaware and Schuylkill company.

6. Baker Library, Harvard University School of Business Administration.

7. “The directors of the inland navigation companies in this State labour under a very disagreeable dilemma,” wrote Schuyler. “They have engaged a large number of men to begin their operations on the 15th of next month and they have not been able to procure any person of the least practicable experience to conduct their operations. This has induced me to take the temporary superintendence of the business until an adequate person can be found may I enreat your interference on the occasion, and your recommendation of the directors to permit Mr. Weston to repair to this place, as early as possible, to avoid the errors we shall otherwise in probability commit. . .” General Schuyler had already begun to realize, said De Witt Clinton later, that the work was too mighty for his grasp.

8. Among the young surveyors who were more or less responsible to Weston at this time was Benjamin Wright, an American in his early twenties, who afterward became the leading American canal engineer. It is also possible that Marc I. Brunei, a self-exiled French royalist,afterward to win fame in England, should be included. At any rate young Brunei made surveys for the Northern Inland Lock Navigation (which later became the Champlain Canal) during the years immediately following his arrival in New York in 1793. He sailed to England in 1799.

9. These were made by James Geddes, afterward engineer of the western section of the canal.

10. It is on record that Weston, in declining the offer of chief engineer, added that he considered it the greatest compliment of his life.

11. Joshua V. A. dark, Onondaga, Vol. II (Syracuse, N.Y. 1849). At that time (1813) to name only three, Telford was 56, Rennie 52 and Marc I. Brunei 44 years of age.

12. Communicated in 1806 to the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, and published in Vol. I of the Memoirs of the Society (Philadelphia, 1808). A plan and elevation of this bridge may be found in Owen Biddle’s Young Carpenter’s Assistant (Philadelphia, 1805).

13. The elder Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), at this time engineer of the first Philadelphia waterworks.

14. This draft has doubtless long since disappeared. No cast-iron bridge was built in the United States until 1836. Thomas Paine had urged his cast-iron arch, with a rib for each of the 13 states, for this same location as early as 1786.

15. Within the present limits of Bronx Park, just south of the Bronx and Pelbam Parkway.

16. Latrobe was the first in America to use cast-iron pipe; this was on the Philadelphia Waterworks, in 1804.

17. Gent. Mag. October 1792, p. 1054, under “Marriages, lately.”

About Billerica at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century

Excerpted from the book The Peabody Sisters by Megan Marshall, copyright ©

2005. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

All rights reserved. [contributed by Howard Winkler]

Eliza’s spirits rose with her expectation that her own teaching days would end once Nathaniel completed his [medical] training. She looked forward to writing poetry again, and as she nursed the infant Elizabeth, she made plans for a small, select boarding school that she could run in a spare room of the farm-house - a “family school.” She hired a young woman to cook and mind the baby during school hours in exchange for board and lessons. Eager to give her namesake a more official welcome into the world than she had received, Eliza had her first daughter baptized when she was four days old in the First Church of Billerica. There her name - Elizabeth Palmer Peabody - was duly entered in the church records on May 20,1804.

That year the town of Billerica itself was alive with new hopes. Thirty miles inland of the great port towns of Boston and Salem, Billerica was embarked on what then seemed a steady progress from farm village to commercial center. Billerica lacked the settled aristocracy of nearby Andover, and the Peabodys might well have worried about how they would find enough “young ladies” to fill Eliza’s school. But in the past ten years the town had grown in population from almost 1,200 to nearly 1,400, swelling with a new class of residents lured by novel business prospects. In 1803, the ambitious Middlesex Canal project had just been completed, and now this twenty-five-mile-long man-made waterway - the first traction canal in the nation - promised to speed farm goods and lumber from upper New England to the port of Boston, avoiding the rocky seacoast and passing straight through Billerica. Then, shortly after the Peabodys arrived, the Middlesex Turnpike received its charter; early plans called for this first direct wagon and stage route from the north to pass through the center of Billerica on its way to Cambridge, attracting business to the town along with the new canal. Billerica, indeed all of New England, was beginning to feel that prosperity had arrived with the new century to chase away memories of the war and its chaotic aftermath. [Eliza & Nathaniel were the parents of the sisters - Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia.]

Out for a Walk along the Canal with my Dad

by Thomas (Tom) Clifton Proctor, Associate Museum Director, Mayborn Museum

Complex,

Baylor University, Waco, Texas - <tc_proctor at yahoo dot com>

[Tom completed the Finding Aid/Index to the records of the Middlesex Canal Corporation for the University of Massachusetts, Center of Lowell History, in April 1984. His master’s thesis is titled: “The Middlesex Canal, Republican Ideology and the Process of Emulation: a Study of the Impact of Beliefs and Models on Technological Development in Late Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts”. Tom has been a Certified Archivist since 1991.]

Middlesex Canal during one of our walks in the late 1960s

Father’s Day 2008 has just past and my thoughts are inevitably drawn back to the walks that my dad and I had together along the Middlesex Canal. Although my dad died more than a decade ago, those memories and the lessons learned from lingering along the canal remain fresh and inspiring.

The Middlesex Canal has had a magical and engaging quality since its inception, that makes one appreciate Loammi Baldwin’s final words to his children to promote the public good and cherish the Middlesex Canal (Loammi Baldwin Jr. to James F. Baldwin, December 14, 1807, Baldwin Family Papers, Essex Institute, Salem, MA).

My dad (Maurice Clifton Proctor, Jr.), Clif, as he liked people to call him, had an infectious sense of the dynamism, texture, and feel of real history-objects, architecture, archives, people and places. For dad good history, like good food, was meant to be relished and taken in so as to become part of one’s life today and to energize one with new hopes for tomorrow.

Throughout my childhood my dad made it a habit to take my brother and me to the buildings and places in the greater Boston area where both the great and ordinary events of American history had transpired. Through these marvelous time-traveling journeys with my dad, I felt connected and inspired with the reality of what other people had done who had gone before me. As a result, my curiosity was peaked to explore further. Hence, my life-long habit of visiting museums, archives, libraries, and historic sites throughout the United States and my 25+ year career in museums and archives that currently finds me mentoring the next generation of museum professionals at Baylor University.

Now what of those transformative walks along the route of the Middlesex Canal? Certainly they were special times with dad and me venturing out from our 1750s center-chimney colonial house where we lived in Reading to trek the canal’s path from Boston to Lowell in the 1960s and 1970s. It was special to me because he cared enough to make the time to be with me. Dad frequently used to say to anyone who would listen, “Enjoy your children while they are young because before you know it they’ll grow up and you won’t get that time back.” Great advice that he lived! And he was so right. My own son, who was it seems to me born moments ago, while we lived in Montana, has just graduated from high school here in Texas-where did the time go?

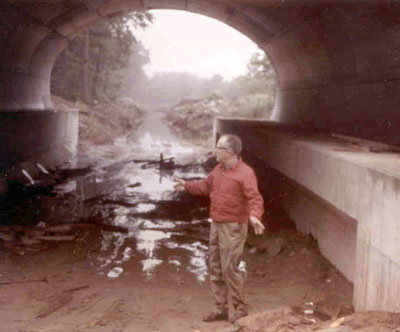

Clif Proctor in the Middlesex Canal, Route 129 overpass, Wilmington

Dad made these journeys along the Middlesex Canal special by the attention and time he gave to me, the power of his words and imagination that he shared with me and the genuine substance of seeing actual locations where the canal was built, operated and ultimately pushed aside by the technological progress that it had made possible. We made journeys throughout the four seasons over a period of years and under all sorts of weather conditions. After a while I could sense and feel the wonder of traveling along the canal and really appreciate the natural environment and how it was ultimately fighting against the very existence of the canal. We even journeyed along the Merrimack River and into New Hampshire. At such times I imagined that I could feel the pulse of raw goods journeying towards Boston and manufactured products returning northward.

Sometimes dad and I would walk quietly along the sections of the Middlesex Canal that still held water in Woburn, Willington, Billerica and Lowell. We’d admire the architecture of the Baldwin Mansion, Count Rumford House, the two Toothaker Taverns and the canal tollhouse from Middlesex Village in Lowell (relocated to Chelmsford Center) and talk about the stories these structures could tell. Of course, there were those technological marvels of canal locks and even the footprints of aqueducts in Wilmington (Maple Meadow) and Billerica (Shawsheen River)!

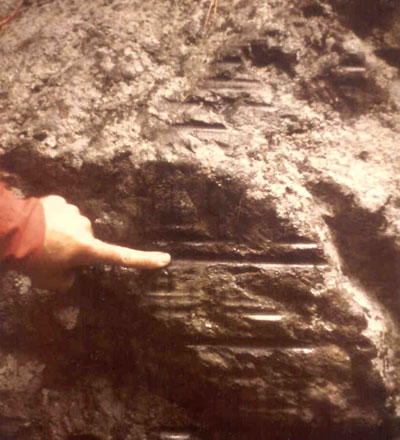

Clif

Proctor points to the canal's lasting impact on the environment - towline

grooves in boulder on the S-curve near Maple Meadow, Wilmington

Anyone who remembers my dad knows that those quiet times were brief and that he was passionately assertive, outgoing and gregarious. Clif certainly accepted without reservation the Texas maxim: “If you don’t blow you own horn, someone else will use it as a spittoon!” He loved history and the natural world, serving on both the Reading Antiquarian Society and the Reading Conservation Commission. He was delighted when highway funds were spent to include the preservation of the Middlesex Canal in the Route 129 bridge overpass in Wilmington. I can still see and hear him talking about the virtues of preserving our heritage while standing in the center of the canal! It is as Professor Elting E. Morison often used to say:”…if we are to control the technological world we are building, we must first command ourselves, and that command rests upon our understanding of, and respect for, the fundamental organization of our being….some feeling for what was done before may help in deciding what to do next.” (Elting E. Morison, From Know-How to Nowhere: The Development of American Technology, New York: Basic Books, 1974, pp. 4-5.)

Clif, my dad, definitely instilled in me a respect for the inspiration and direction that can be found in the human element of our lives, which realizes that what we are able to do today and tomorrow is possible because we stand on the shoulders of people that have gone before us. He made this lesson real for me by pointing to the grooves left by the long towlines in the boulders along the canal at the S-Curve to avoid the Maple Meadow in Wilmington.

Dad was right: we can discover lessons from past generations that will make our world just a little bit better. I think the real question to us is whether we care enough to make the time for quiet and not-so-quiet journeys of discovery along the banks of the old Middlesex Canal. The canal is a feat of human ingenuity - an old friend - with many lessons yet to teach.

THE OLD MIDDLESEX CANAL – 1898

[The following article was contributed by Andrea Houser a member of the Association. Daniel Gowing, her great grandfather, was lock tender at the Gillis Lock. He was featured in a newspaper article found in Mary Gowing Swain’s, Wilmington scrapbook (Wilmington Public Library, call no. W 974.444 Wil).]

Daniel Gowing of Wilmington, midway between Boston and Lowell, on the line of the Southern division of the Boston & Maine, is one of the few living employees of the old Middlesex Canal Company, which before the days of railroads was an artery of great importance from the sea to Lowell and the north.

Mr. Gowing was associated with the scenes of more than a half century ago, when canal boats plied a waterway designed for them in Massachusetts with much of the regularity expected of coastwise packets. But times have changed to a remarkable degree since this venerable gentleman was a lock tender in Wilmington. He knew the canal and witnessed the competition between canal boats and steam cars, which eventually sent the canallers out of commission.

The history of this competition is very interesting. For miles the steam railroad skirted the banks of the canal in fact the big ditch was never out of hearing of the shrill screech of the locomotive whistle.

At the Gillis lock in Wilmington where for 10 years Mr. Gowing was employed, the railroad was separated from the canal by not more than 50 feet of embankment, and the two enterprises as they continued through Woburn and Winchester to Boston were almost shoulder to shoulder.

In 1808, the Middlesex canal was opened for business. Prior to that time the transportation of freight from the seaboard was accomplished by baggage wagons and caravans. Perhaps the greatest engineering difficulty of the canal, which connected the Merrimac at Chelmsford with the Charles River in Boston, was the series of locks at Horn pond in Woburn.

Three double locks were necessary to accomplish the purpose. The first was wood, near the corner of Canal and Sturgis Streets, below which was a basin; the second of wood, about 1000 feet southerly of the first while the third of stone was near the foot of Pond Street.

Jonathan Clough for a long time was in charge of this particular lock system. Another lock, toward Lowell was built at Wright estate on Kirby Street and still further toward Lowell was the Gillis lock where Mr. Gowing was in charge.

The old gentleman delights to tell of the historic waterway and its traditions. It was during the regime of Richard Frothingham the historian, that he assisted in the unique method of transportation. The Gillis lock was not so important as the Horn pond series some seven miles nearer Boston, yet Mr. Gowing found his time fully occupied in getting the canal boats past his station. There was ordinarily a depth of about five feet in this particular lock, but it could be flooded to 10 feet if necessary. At the Horn Pond locks the great gates in the upper section were opened till the current backed against the second gate. The boat was floated through the first lock and when the gates of the first section had been closed the second and third were opened in respective order till the craft had reached the lower canal. In going in the opposite direction or toward the Merrimac, the process was reversed.

Of course the canal had its express or passenger boats just as railroads of today operate freight and passenger trains. The packet of the period was the Gen. Sullivan and she had the right of way. It is said that the captain of this passenger boat was considered a most fortunate fellow because of the position he occupied. But this same master of the Gen. Sullivan did not hold a pilot’s certificate nor did he make use of the mysteries of compass and charts, sextant and quadrant. He took an occasional observation, but it extended only over the backs of the tow horses. He could not conscientiously drink a toddy on raising a light, the order of the light determining the number of drinks to the success of his passage, because no light houses welcomed him to land from off shore. When the Gen. Sullivan’s commander lost his reckoning he jabbed a setting pole into the bank of the ditch and at once corrected his position.