Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 48 No. 1 | October 2009 |

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

by Bill Gerber, President pro tempore

978-251-4971

To begin with, I wish to extend a great big thank you to the anonymous donor who bought us time to find solutions to the problem of keeping the museum open, also to all who have contributed to our annual fund appeals, and all who have maintained your membership in the Association through the years. Your contributions are appreciated and we, of the Board of Directors, try very hard to make responsible and constructive use of them.

Why, you might ask, is the MCA VP writing the President’s message? As most of you know, we held our Annual Meeting in early May and elected officers for the year to follow. Our President, Nolan Jones, came to that meeting and was reelected; however, Nolan wasn’t feeling well that day. At the end of the meeting, it seemed prudent to get him checked out and so off to Lahey he went. Lahey quickly determined that he was having a stroke and admitted him.

Nolan lost use of his left arm and leg and a bit of speech control. He has since recovered - from most, if not all, of his speech impairment, limited functional use of his left arm and hand, and some leg function, i.e., he is able to walk with a walker and a bit of assistance. Nolan is home now and, however slowly, continues to show improvement. We all wish him continued improvement and hope to have him back whenever he feels able to come.

In late spring, Traci Jansen, Betty Bigwood and Tom Dahill again entertained several classes of third graders from the Wilmington schools at our museum. The purpose, of course, was to introduce the kids to the Middlesex Canal - what it was, how it worked and the contributions it made to the local economy in the decades following the American Revolution. The program was run as a local field trip and, as usual, the kids loved it.

The MCA Board would like to expand Traci’s program, to reach the kids from schools in other towns along the canal. But there is recognition that this would severely tax the Board’s (generally elderly) human resources. In response, working on a grant from the Barker Foundation, Traci developed and conducted a two-day seminar, to begin to teach teachers about the canal, with the intent of decentralizing and broadening the base of those able to teach the subject.

Tom Dahill, Betty Bigwood and I met with two representatives of Middlesex Community College to discuss the possibility of persuading a few students to work as volunteers at the museum. Bill suggested that some of the students might be interested in doing research about the canal and provided an extensive list of potential projects. Now that school has resumed, we should soon know if this initiative will “bear fruit.”

A very long time ago, Tom Raphael and Susan Keats took on the task of placing the entire Middlesex Canal on the Register of Historic Places. Their work was completed and turned over to the Mass. Historical Commission two years ago. MHC decided to use “our” submission as a vehicle to register some additional structures and properties. Recently there have been stirrings that MHC’s “package” is about ready to be forwarded to the Park Service. (Keep your fingers crossed.)

You may be aware that the first construction phase of the Bruce Freeman Rail Trail (BFRT), through Chelmsford, was officially opened in late August. Subsequent construction phases will eventually extend this trail south to Concord, Sudbury and eventually Framingham. Some of us think there is merit in linking sections of the Middlesex Canal towpath to the BFRT; e.g., among the many benefits, it would considerably widen bike-to-work opportunities, improve access to the commuter rail station in North Billerica, and, if eventually linked to other trails (e.g., the Yankee Doodle and Reformatory Branch Trails), would provide a “doable” loop of about 30 miles. To promote this idea, Doug Chandler, Traci Jansen, J. J. Breen and yours truly set up a table, representing the MCA and MCC, at the ribbon cutting. J. J. also prepared a banner, which he placed in the “tunnel” under Rte. 3, noting that the canal crossed the end of the BFRT at its northern terminus near the Cross Point Towers (aka Wang Towers) near the intersection of Rte. 3 and I 495.

Neil Devins, our membership director, contributed significantly to the value of a Wilmington Scout’s walking trail, an Eagle Scout Project. Neil designed a display illustrating how the canal path coincided with the “Town Park Path”, and prepared a “tour guide” for that portion of the trail that followed the canal and towpath. Periodically, Neil assists with trail maintenance and updates and replenishes the brochures available from a kiosk located just off of the parking lot for the Town Park a short walk to the north of the trail head. (The park is on the west side of Rte. 38, about a mile north of the Woburn line.)

Many years ago, our museum acquired a working model of a canal lock, which we’ve used uncountable times to demonstrate exactly how a lock works. For reasons not known, the upper miter gates of the model never quite “met” correctly. J. J. Breen, a new member of our Board, undertook the task of adjusting the gates, which required considerably more effort than expected. The good news is that he succeeded and, when closed, the upper gates now form a proper miter joint.

Are any of you file experts, or do you have time to work on becoming one? The MCA recently obtained the personal files of five past Association Presidents and one of its principal early researchers. These are composed of both administrative files and historical documents and artifacts. No doubt some could be discarded, but some should also be retained. Should they be integrated? Which? How? Why? Help!!

Elsewhere in this newsletter, you should find Traci Jansen’s review of a new book, “Life on the Middlesex Canal”, recently published by Alan Seaburg and Tom Dahill. You may recognize the names from their prominent roles in preparation and publication of another book: “The Incredible Ditch”. Early word is that it is well researched and a “good read”.

Over the past several months, the board has promoted private use of the museum and meeting room to raise money to meet our own monthly rental expenses. While these efforts have raised some money, it has never been sufficient; probably the best we’ve done is to raise about one-third of what we needed, and just as often not even that. If any of you have ideas for raising money and some time to devote to implementing them, this is a matter we seriously need some help with.

A tribute to the Middlesex Canal is planned at the end of Canal Street by the Raymond Hynes Development Company when construction begins on their new building. The current recession has delayed their progress.

In the lobby of the newly constructed Hynes building at 53-85 Canal Street is a framed copy of the definitive map of the Middlesex Canal as prepared by Col. Wilbar M. Hoxie. This was prepared for the acceptance of the Middlesex Canal into the National Registry of Historic Places.

Bill Gerber

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE - Bill Gerber

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

WHEN BOSTON WAS CUT IN TWO - MCA Fall Meeting

THE MIDDLESEX CANAL COMMISSION - Tom Raphael

JAMES SULLIVAN’S RESTING PLACE - Howard Winkler

LETTERS, FIRST PUBLISHED ... , J. L. Sullivan, submitted by Howard Winkler

CANALS OF CAMBRIDGE AND THE MIDDLESEX CANAL - Alan Seaburg

LIFE ON THE MIDDLESEX CANAL - book review by Traci Jansen

FOLKLORE AND MUSIC OF THE RIVERS AND CANALS - Bill Gerber

FUNCTION ROOM RENTAL & MISCELLANY

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

First Wednesday: MCA Board of Directors’ Meetings - The Board meets at the Museum, from 3:30 to 5:30pm, the first Wednesday of each month from September to June. Members are welcome to attend.

October 7-12: Thru-hike, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal; reservations required; Tom Perry, 301-223-7010.

Saturday, October 3: 7th Annual Historic Middlesex Canal Bike Ride, co-sponsored by the Somerville Historic Preservation Commission, the Middlesex Canal Commission, and the Middlesex Canal Association. Meet at Sullivan Square T station (to the right of the main entrance, by the historic canal plaque) at 9:00am. We will follow the route of the old Middlesex Canal (1793-1853) to Lowell, with lots of stops along the way to see remnants of the canal, including some restored sections and the home of the canal’s designer, Loammi Baldwin). We will get to Lowell in time to take the train back to Boston. The total distance is 38 miles (but riders can also catch earlier trains at 20 miles in Wilmington or at 28 miles in North Billerica). See www.middlesexcanal.org for details or contact Dick Bauer <dick.bauer at alum dot mit dot edu>, 617-628-6320), Robert Winters (robert@middlesexcanal.org), or Bill Kuttner <bkuttner at ctps dot org>.

October 16-18: CSNY Fall Study Tour - focus - Restored Nine Mile Creek Aqueduct at Camillus. Hq. Clarion Inn and Suites 100 Farrell Rd. (near I-690 and I-90 junction). For info, contact Michele Beilman <mbeilman at twcny dot rr dot com>.

October 16-18: Canal Society of Indiana’s fall tour will explore the Ohio & Erie Canal in Piqua and New Bremen, Ohio. Questions? 260-432-0279 or <indcanal at aol dot com>.

Sunday, Oct 18, 2009: MCA-AMC Fall Walk. Middlesex Canal. Meet at the Middlesex Canal and Visitors Center in N. Billerica. Level, 5 miles, walk along the historic canal north to Chelmsford and back, 1:30-4:00pm. Museum opens at noon. No registration required. Joint with Appalachian Mountain Club. Info: www.middlesexcanal.org or Roger Hagopian (781-861-7868). Leader: Robert Winters (617-661-9230; robert@middlesexcanal.org).

Directions to the Museum/Visitors Center: Telephone: 1-978-670-2740.

By Car: From Rte. 128/95, take Route 3 toward Nashua, to Exit 28 “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road toward North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at a fork. After another ¾ mile, at a traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A. Go about ¼ mile to a 3-way fork; take the middle road, Talbot Street, which will put St. Andrew’s Church on your left. Go about ¼ mile and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the falls, where Old Elm becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the falls.

From I-495, take exit 37, N. Billerica, south to the road’s end at a “T” intersection, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700’ and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street.

By Train: The Lowell Commuter Line runs between Boston’s North Station and Lowell’s Gallagher Terminal. Get off at the North Billerica station, which is one stop south of Lowell. From the station side of the tracks, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station and Faulkner Streets on the right side.

October 24: Program, lunch & bus tour of the Farmington Canal in the Farmington Valley, CT; reservations required, Carl Walter (860-653-2673).

Sunday, November 8, 2009: MCA Fall Meeting will be held on Sunday, November 8 at 2PM at the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center at 71 Faulkner Rd in North Billerica. David Dettinger, a Director of the MCA and author of the definitive study of the Canal in Boston will introduce the primary speaker, Duane Lucia. Mr. Lucia, President of the West End Civic Association is an aficionado of Charles Bulfinch, Boston’s most famous architect and designer of the Bulfinch Triangle. Together they will give a lively presentation titled “When Boston was Cut in Two”. Please join us. (See above for directions to the museum. Find a more expansive description following the Table of Contents.)

April 9-11, 2010: “Hoosiers on the Move”- Headquarters: Comfort Inn, Richmond, Ind., 765-935-4766; room rate: $61.60 includes tax. Tour will cover the Whitewater Canal, National Road, Quakers, Politicians, and Underground Railroad in Wayne County, Indiana. Carolyn Schmidt, (<indcanal at aol dot com>; 260-432-0279).

April 16-18, 2010: Pennsylvania Canal Society Spring Field Trip: central/west portion of the Main Line (Philly to Pittsburg) Canal. Contacts: Bob Keintz <bobkeintz at gmail dot com> and Glenn Wenrich <gaw31 at frontiernet dot net>.

May 21-23, 2010: Spring Study Tour - focus - Hudson River/Champlain Canal PCB Cleanup and Dredging Operation at Ft. Edward. Hq. Queensbury Hotel, Glens Falls. Check www.canalsnys.org for updates.

September 19-23, 2010: World Canals Conference, Rochester, NY. Contact: www.worldcanalsconference.org. Post conference tours Friday, Sept 24. Check www.wccrochester.org.

October 1-13, 2010: Study tour of south German waterways. www.canalsnys.org

WHEN BOSTON WAS CUT IN TWO

Fall Meeting of the Association

The Fall Meeting of the Middlesex Canal Association will be held on Sunday, November 8 at 2pm in the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center at 71 Faulkner Rd in North Billerica, MA.

Brief Introduction: David Dettinger, a Director of the MCA, and author of the definitive study of the Canal extension in Boston will draw attention to the fact that the Canal extension bisected Boston from 1810 to 1830.

The Middlesex Canal (1803-1853), dug by hand from the Merrimack River at Lowell to the Charles River at Charlestown during the second term of George Washington’s presidency, played a major role in the development of Boston. Boats were drawn by horse to the Charles River. There they were pulled by chain across the Charles River to the northern inlet of the scalloped peninsula that was Boston, across the canal and down Mill Creek to the long wharfs of the Boston Harbor.

Duane Lucia, President of the West End Civic Association and an aficionado of Charles Bulfinch will be our main speaker. Mr. Lucia will portray Bulfinch, not only as one of Boston’s greatest architects, but also as the person solely responsible for “putting the ‘proper’ in Proper Bostonian”. He designed some of Boston’s most notable buildings (State Capital, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harrison Grey Otis etc.) and laid out a plan which led to the filling in of the Boston Mill Pond creating the Bulfinch Triangle. Here the Canal bisected the Boston Peninsula at Canal Street on its way to Haymarket Square and the shores of the Atlantic.

Please join us for a delightful afternoon. Phone 978-670-2740 or see www.middlesexcanal.org for additional information. Handicapped accessible. Free.

THE MIDDLESEX CANAL COMMISSION

by Thomas Raphael, Chairman

The nomination of the full route of the canal (including the overbuilt areas) to the National Register is currently awaiting completion of a special version of the MAP BOOK bring prepared at the request of the Massachusetts Historical Commission. Features being added to the special version will coordinate the Nomination Narrative with the Area Data Survey Matrix. The first draft is being reviewed and when completed will allow the Nomination to be submitted to the National Park Service in Washington.

The Phase I, Mill Pond/Canal Project in Billerica is unfortunately delayed due to the uncertainty of ownership of the Cambridge Tool & Manufacturing Company, whose property was formerly that of the Middlesex Canal Company and encompasses all of the project.

Phase II has been started and has produced a study of all the approximate 12 miles of extant canal segments. There are 19 segments ranging from 700 ft to 6000 ft in length. Five segments have been rated high for restoration.

Woburn, Segment #5, Alfred to School Streets, has favorable City support and is progressing from Concept to 25% Design.

Wilmington Segment #6, Main Street to Burlington Avenue, and including the Ox Bow and Maple Meadow Aqueduct, has been presented to the Wilmington Town Community Development Technical Review (CDTR) and is awaiting their recommendation to the Selectmen.

The Commission is carrying all three projects along concurrently with the intention that the first to meet all the 25% Design criteria will be submitted to receive the Federal Highway Enhancement funds to proceed to 100% design and construction.

JAMES SULLIVAN’S RESTING PLACE

by Howard Winkler

He lies in a shared tomb in the Granary Burial Ground located on Tremont Street in Boston.

Gov. James Sullivan on left – Gov. Richard Bellingham on right

The tomb is located in the back on the right, and is marked by a placard which reads -

Governors Richard Bellingham (1592-1672) and James Sullivan(1744-1808) are both buried in Tomb 146.

The reason for the shared tomb is explained in the inscription on the slab over Bellingham’s grave, and is presented below.

The inscription on the slab over James Sullivan’s half of the tomb except for the topmost words, JAMES SULLIVAN, ESQ. is illegible. With assistance, acknowledged at the end, the following epitaph was found.

THE FAMILY TOMB OF

JAMES SULLIVAN, ESQ.

LATE GOVERNOR AND COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE

ON THE 10TH DAY OF DEC’R, A. D. 1808,

AGED 64 YEARS. HIS REMAINS ARE HERE DEPOSITED.

DURING A LIFE OF REMARKABLE INDUSTRY, ACTIVITY, AND

USEFULNESS,

AMIDST PUBLIC AND PRIVATE CONTEMPORANEOUS AVOCATIONS,

UNCOMMONLY VARIOUS,

HE WAS DISTINGUISHED FOR ZEAL, INTELLIGENCE, AND FIDELITY.

PUBLIC-SPIRITED BENEVOLENT, AND SOCIAL,

HE WAS EMINENTLY BELOVED AS A MAN, EMINENTLY ESTEEMED AS A

CITIZEN AND EMINENTLY RESPECTED AS A MAGISTRATE.

HUIC VERSATILE INGENIUM SIC

PARITER AD OMNIA FUIT, UT, AD, ID UNUMDCERES

QUOD CUM QUE AGERET.

This wonderfully gifted man was always ready to serve,

but never sought glory.

Richard Bellingham was governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1641 to 1642, and again from 1665-1672. The epitaph on his tomb is legible, and explains the reason for the shared tomb.

HERE LIES

RICHARD BELLINGHAM, ESQUIRE

LATE GOVERNOR IN THE COLONY OF MASSACHUSETTS,

WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE ON THE 7, DAY OF

DECEMBER, 1672.THE 81ST YEARE OF HIS AGE.

VIRTUE’S FAST FRIEND WITHIN THIS TOMB DOTH LYE,

A FOE TO BRIBES, BUT RICH IN CHARITY.

THE BELLINGHAM FAMILY BEING EXTINCT,

THE SELECTMAN OF BOSTON IN THE YEAR 1782,

ASSIGNED THIS TOMB TO JAMES SULLIVAN, ESQ.

THE REMAINS OF GOVERNOR BELLINGHAM

ARE HERE PRESERVED,

AND THE ABOVE INSCRIPTION IS RESTORED

FROM THE ANCIENT MONUMENT.

In addition to the two governors, there are five members of the Sullivan family also in the tomb; there are no other Bellinghams.

Sources:

Inscriptions and Records of The Old Cemeteries of Boston, compiled by Robert J. Dunkle and Ann S. Lainhart, 2000 (found in the Minuteman Library

Network)

The Pilgrims of Boston and Their Descendants by Thomas Bridgman, 1856, pp. 15 to 18 (found in Google books; to access enter title and author as key words into a browser)

____________________

Thanks to

Eva Murphy, Reference Librarian, State Library of Massachusetts for the locating Governor Sullivan’s burial place.

Tom Raphael, our resident Latin scholar for providing the translation.

Geraldine Kaye, New England Historic Genealogical Society, member, who found The Pilgrims of Boston and Their Descendants in Google Books.

LETTERS, FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE BOSTON DAILYADVERTISER (1818),

IN ANSWER TO CERTAIN INQUIRIES, RELATIVE TO THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

BY JOHN L. SULLIVAN, AGENT OF THE CORPORATION. No. III

This is the third of five letters. The first was published in the October 2008 issue of Towpath Topics and the second in the April 2009 issue. The letters have been transcribed by Howard Winkler from an electronic facsimile found at the Tisch Library, Tufts University. The original spelling and punctuation were retained.

Mr. Hale — The business of the Canal now becomes regular. The well disposed were not displeased with the control that protected them as well as the Canal — and the difficulty of enforcing the collection was obviated by holding the property for the toll due. To add in the regulation of the water — convey and receive intelligence, the packet was established to run from Charlestown to Chelmsford with passengers, and Concord river before mentioned as appurtenant to the Canal was opened for ten miles to old Concord, and such toll levied as the business would bear. Several additional and original acts were obtained in New Hampshire, and the plan of the works on the river determined on and commenced.

The Union Bank employing me to reduce the affairs of Blodget’s canal to order, it was accomplished, so that the shares pledged for a large loan became of so much value as to save the debt: a number of the proprietors of Middlesex Canal being induced to join with me in the purchase of them, with a view to renew the canal and make it subservient to the main design - the opening of the river.

Amoskeig is situated on the east side the Merrimack in the town of Manchester, 30 miles from the head of the Middlesex Canal. The fall is about forty-five feet perpendicular measurement—the whole extent, including the channels and dams, which form the upper entrance down to the four locks at the lower end, is about two miles. — It has every year since the purchase been renewed in part; and in 1816 it was completed in the most substantial manner. The expense to the new proprietors has been about 35,500 dollars, besides the application of income till the last year, when the first dividend was declared. The tolls have amounted to $3000. This canal is estimated at 50,000 though a much greater sum had been previously laid out. It has the business that goes by rafting to Newburyport, as well as to Boston.

Below this canal there are seven falls within the state of New-Hampshire, included in one act of incorporation, in a distance of fifteen miles on the river, nine of which immediately below Amoskeig, is converted by law to a canal and pays toll per mile. The lower work requires a separate toll.

The plan of all these locks is the same, varying only according to local circumstances. The execution was difficult and hazardous from their situations. The banks being high, and the river subject to freshets, they were unavoidably placed in its bed.

Each lock stands at the foot of the falls, connected with the nearest shore. A dam extends from the outer wall up the river to the still water, forming a basin.

That at Merrill’s, Moor’s and Cromwell’s falls are from 100 to 150 rods in length, constructed of timber, stone and plank. The others are of less extent, and vary as the situation required. When the freshets are high, these locks are covered with water; floating things pass over them, but the parts exposed to damage are well protected. In winter, precautions for security are taken: the gates chained, locked and fixed open — thick plank are set into grooves, which prevent any thing from passing through. — The walls are of large split stone, carefully united with iron. There has been no damage of any importance sustained, in the course of six or seven years.

The Union Locks and Canal, with all the intermediate labour, have cost about 50,000 dollars. The tolls last year thereon amounted to more than 3000 dollars, and the first dividend was last year credited to the Middlesex account, being only a part of the income, the other part being employed in erecting tenements for the lock tenders.

In Massachusetts, Wicasee canal, situated four miles from the head of the Middlesex, in a secure passage between an island and the main land, cost 14,000 dollars. The tolls amounted last year to about 700, and were employed in erecting a house and paying some small demands on this work. An act authorizing its construction was passed by the Legislature in 1813.

To shew that the directors were personally attentive to their trust I must beg leave to mention that when the Union Canal was begun, I hoped to dispense with locks at some places, and do with channels only: but coming to ledges, and finding the water would run too wild and swift, it became necessary to decide whether to erect more locks or not. The Board of Directors went up, and seeing the impossibility of doing without them at these places also, they decided to erect five more that same season, if practicable. This resolution was not taken till about the 10th of July, and no preparations had been made. Yet they were erected by the 1st of December. The season being uncommonly favourable, and the number of men in all the departments about five hundred.

The Locks of the Wicasee and Union Canals thus standing in the bed of the river where it was impossible to get rid of the water, and it being necessary to sink the foundation so much below the lowest water as to admit the boats into the locks — as well as to rise so high as to accommodate the variations of its surface ten feet, great caution was required to have secure foundations –suitable stone for the walls was only to be procured from a distance of one, two or three miles, and in several instances were to be conveyed across the river. Yet with the agreeable circumstance of having interested a number of the principal gentlemen of the neighbourhood in the proprietary and direction, we have the satisfaction to think the business could not have been effected at less cost.

Eight miles above Amoskeig, Hookset Canal is situated on the falls of that name in the town of Dunbarton, measuring about 16 feet perpendicularly. There were some circumstances to render this an expensive undertaking. It was in possession of owners who were not easily bought out — the lower Lock was to be sunk deep in the water where the digging was rocky and difficult — the guard locks required great support and defence. The expense including the purchase of the mills and dam was about 17,000 dollars besides the income for several years. This Canal has made one dividend equal to 4 per cent. being only a part of its net income. And but for the cost of certain improvements last year it would have divided 6 per cent. It is now complete.

The Canal at Bow is more considerable — it extends half a mile through ledges and difficult ground — a dam is thrown across the river 5 or 600 feet in length, in the midst of the falls — which raises the water thro’ the channels of Turkey falls, and at the same time fills the Canal – the descent is 25 feet by three Locks, supported by very strong walls. The mode of constructing all these Locks is different from those of the Middlesex, and tho’ of timber they are so framed and supported by stone as to be very durable — The cost of Bow Canal was almost 21,000 dollars — Its income has been 1800 dollars — The 1st and 2d dividends after several heavy deductions for completion, were $7 a share, or about 6 per cent.

These works form together the chain of communications between Boston and Concord — to the upper landing where the north-east trade comes in the distance is eighty five miles by water.

The proprietors of Middlesex Canal do not indeed own the whole, but they have a predominant share in most of them — And I cannot but observe here that those who have invested money to a considerable amount and at some risk, to lighten the burden on the Middlesex Incorporation, deserve thanks at least, from those who have not.

In the course of these transactions there have been two assessments, and perhaps the most satisfactory way to answer the desired inquiry will be to state a summary of the principal heads of the annual accounts; and I hope the public will excuse the occupation of a column of your paper with this trespass on its attention, in order that those who wish it, may have a view of the whole subject—and the satisfaction of seeing that there has been a useful appropriation of a large sum not derived from assessments. – The voluminous details from which they are made are within the reach of every Proprietor.

| Payments in the course of ten years viz: | ||

| Old debts or claims paid, | $ 18,337,86 | |

| Interest on debts and loans, | 20,207,87 | |

| Extra expenses, lawsuits &c. &c. | 11,232,99 | |

| Repairs, | 61,773,36 | |

| Improvements, | ||

| Cost and current expenses of | 27,365,48 | |

| Boats, | 12,560,80 | |

| Wages, salaries and commissions to all persons employed in the management 10 years, | 66,356,42 | |

| On the auxiliary Canals, Locks and Channels, | 87,234,49 | |

| Outstanding debts to balance, | ||

| These payments have been made, from the following sources, | ||

| Outstanding debts for toll previous to 1808 | $ 7,972,17 | |

| Income of | 1808 | 7,983,64 |

| 1809 | 9,454,14 | |

| 1810 | 15,473,31 | |

| 1811 | 14,196,76 | |

| 1812 | 12,656,33 | |

| 1813 | 16,867,81 | |

| 1814 | 28,564,50 | |

| 1815 | 29,238,27 | |

| 1816 | 31,778,22 | |

| 1817 | 26,114,08 | |

| 192,327,06 | ||

| Income from boats &c. | 3,612,35 | |

| Dividends of the auxiliary Canals, | 2,220 | |

| Assessments | 104,000 | |

The decline of the income of 1817, is to be attributed to two causes; both of which were temporary. The interruption of the canal for six weeks to rebuild Shawshine Aqueduct, and the extraordinary stagnation of business, between town and country the last season. Those who are conversant with trade, must be well acquainted with the fact.

The report of April 1817, was founded on the rational probability of an increase instead of decline of the toll, and on the expectation that the aqueduct would not cost so much as it has by several thousand dollars.

This is to be attributed to the impossibility of calculating accurately the expense of a job subject to so many contingencies. When a new thing is to be done of the nature of which we have some experience, it is practicable to make an estimate. But no one in this case can pretend to it; as the stone lay in various places distant sixteen miles, were to be split, hauled, boated, unloaded, and wrought into high walls. The old abutments were partly to be taken down, and a great quantity of earth to be moved. The old and the new thus blended, together with the uncertainty of time and therefore of the boarding bills, left the whole a matter of experiment; Besides that, it would have been the worst economy imaginable, to have slighted a construction of this importance, in any respect.

Another cause of the committee’s disappointment may have been the cost of the low-water lock at Charlestown, and the propriety of availing of an opportunity at mid-summer of putting the canal and the several locks, wasteways, aqueducts, and culverts in good order; and even to restore the trunk to its original depth in several places.

The expense of these various jobs, may have prevented the dividend of a few thousand dollars; but as it was proper to save them from the greater evil of having the canal interrupted perhaps in the midst of business the next season, or of incurring twice as much expense in the spring; the anticipation of the present disappointment was not sufficient to prevent the performance of a duty.

The committee’s report of 1811, was predicated on the presumption that much slighter, and fewer works on the river would answer the purpose.

I am happy to think the general good order of the canal, the institution of the fund for repairs, now to commence its operation, and the regularity and dispatch with which business is carried on between Boston and Concord, will suspend opinion until the trial of the present concurrence of favourable circumstances, which now for the first time occurs.

The manner of carrying on the business, the expense of management, and the basis of future expectation must claim another column of your useful paper, for the satisfaction of those who may incline to pursue the inquiry.

J. L. SULLIVAN

THE CANALS OF CAMBRIDGE AND THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

by Alan Seaburg

Bill Gerber, Vice-President of the Middlesex Canal Association and persistent scholar seeking the discloser of the complete history and impact of the old Middlesex Canal upon its historical time, has suggested in a 2009 email as one of some “project ideas” to be examined the following: Copy and catalog all (or any portion of) available historical references to the full complex of related canals (e.g., Mill Creek/Boston, the East Cambridge ‘four’ [sic] and the Millers [sic] River.)

This would be of value to do because it could help to show, as Gerber has maintained from his own studies, that “By 1815, more than 120 miles of canals and navigable waterways had been opened up throughout eastern Massachusetts and south-central New Hampshire. This network rendered the Merrimack River navigable from Concord, N.H. to tide water, near Haverhill, MA, and linked the Merrimack with the Charles River in Charlestown, MA; which river itself became part of the network. Additional canals, made accessible by the Charles, were built in East Cambridge and Cambridgeport, across Boston through Haymarket Square into Boston Harbor.” 1

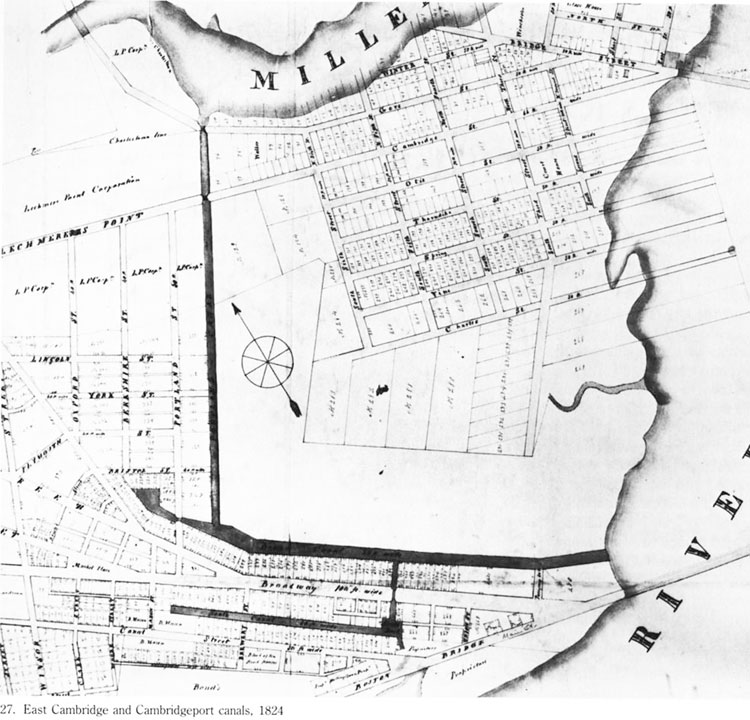

The task of this essay, then, is to examine the topic of the canals of Cambridge and their relationship to the Middlesex Canal. It should clearly be seen as but a preliminary investigation for it could bring forth from others additional sources that need to be researched and then evaluated. We start with this question: what Cambridge canals are we talking about? The answer: The main canals of Cambridge were the Broad Canal, the Cross Cut Canal, the North/Portland Canal, the South Canal, the West Dock Canal, and the Lechmere Canal.

The next step is to understand where they were exactly located. The answer is best found in the detailed and reliable nineteenth century history of Cambridge published in 1877 by Lucius R. Paige, a Universalist minister, biblical scholar, historian, and Cambridge Town Clerk (1839-40, 1843-46) and then its City Clerk (1846-55). 2

Here in his words taken from his history are the locations of these canals of Cambridge:

BROAD CANAL, 80 feet wide, from low-water mark in Charles River to Portland Street, parallel with Broadway and Hampshire Street, at the distance of 186 feet, northerly, from the former, and 154 feet from the latter.”

CROSS CANAL ‘bounded by two straight lines, 30 feet apart, and running at a right angle with Broadway from Broad Canal, between lots 279 and 280, through Broadway, and between lots 263 and to 264 to South Dock.’ This dock was connected with Charles River by a creek, over which was the bridge, long known as ‘Little Bridge,’ at the junction of Main and Harvard Streets.”

NORTH CANAL, 60 feet wide, 180 feet easterly from Portland Street, and extending from Broad Canal to a point near the northerly line of Bordman Farm. This canal was subsequently extended to Miller’s River. According to an agreement, June 14, 1811, between the Lechmere Point Corporation and Davenport & Makepeace, the latter were to have perpetual right to pass with boats and rafts ‘through Miller’s Creek or North River, so called, to North Canal and Broad Canal,’ and to extend North Canal, through land owned by the Corporation, to Miller’s River; and the Corporation was to have the right to pass through the said canals to Charles River, so long as the canals should remain open.”

SOUTH CANAL, 60 feet wide, about midway between Harvard Street and Broadway, from South Dock to a point 113 feet easterly from Davis Street.”

WEST DOCK, bounded by a line commencing at a point in the westerly line of Portland Street, 154 feet northerly from Hampshire Street, thence running parallel with Hampshire Street to a point 100 feet from Medford Street (now Webster Avenue); thence parallel with Medford Street, to a point 100 feet from Bristol Street; thence parallel with Bristol Street, to a point 100 feet from Portland Street; thence ‘parallel with Portland Street 210 feet to the southerly line of land late of Walter Frost;’ thence in ‘a straight line to a point which is on the westerly line of Portland Street, 20 feet southerly and westerly of the northeasterly line of land late of Timothy and Eunice Swan; thence turning and running southerly and westerly on Portland Street, to the bounds of West Dock begun at;’ with the ‘right of water-communication, or passage-way, 25 feet wide, through Portland Street under a bridge. From the main part of Broad Canal to that part called West Dock.’” 3

These five Cambridge canals date from the early decades of the 1800s; the Lechmere Canal – the sixth Cambridge canal in our first list – appears to be from a later period although its original right of way seems to have its origins in several deeds granted in 1834 by the Proprietors of Canal Bridge. Robert Campbell and Peter Vanderwarker, however, in a May 15, 1994 article in the Boston Globe state “The canal was a product of the 1870s, when private developers filled a former marsh to create commercial sites.” That, of course, is after the Middlesex was no longer in business.

Figure 1. East Cambridge and Cambridgeport Canals - 1824

(from Survey of Architectural History in Cambridge, Vol. 1, revised 1988)

Given this data on the Cambridge canals, it was interesting that a further search of Paige’s 1877 history found no references whatever to the Middlesex Canal or to any possible tie it might have had with his town’s local canals. If there had been a connection, if there had been an influence linking them, he either did not know of that fact or chose to ignore it. The same absence of the Middlesex allowing or promoting trade between Cambridge and New Hampshire can be found in the only essay on the Middlesex Canal in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, the official journal since 1906 of the Society. That reference was a general survey article by Brenton H. Dickson simply entitled “The Middlesex Canal.” In his essay - which had originally been given as a lecture to the Society in 1965 - Dickson never mentions the Cambridge canals at all. One would have thought that he would have done so if they had had any major commercial relationship with the Middlesex. Clearly for him the two played either no role whatever or such a slight role in the history of each other’s existence and development that he did not need to comment upon it. Nor for that matter did anyone who heard his lecture seemed to have raised the question that he had omitted a vital fact in the story of the Middlesex.

It is time now to examine the literature directly focused on the Middlesex Canal. The first real scholarly exploration of the Canal - one that is carefully annotated - was by Christopher Roberts – The Middlesex Canal, 1793-1860 – which was published by the Harvard University Press in 1938. It was based on his doctrinal dissertation at Harvard. Nowhere in his thorough study does he mention the canals of Cambridge. Indeed, the book’s index has only four references to “Cambridge” and these are merely general references. The next extensive account of the canal – The Old Middlesex Canal published in 1974 by Mary Stetson Clarke – also completely ignores any possible role by Cambridge canals in the story of the old Middlesex. Indeed, the word “Cambridge” never appears in the book’s index.

Now what about the records of the Middlesex Canal Corporation itself – do they reveal any connection with the small canals in Cambridge and the Middlesex? Fortunately these records exist in the collection of the library of the University of Lowell – and fortunately they have been beautifully inventoried and registered in 1984 by Thomas C. Proctor. He did this as his internship project for Professor R. Nicholas Olsberg’s course on “Archival Methods.” It helped him earn his Master of Arts degree in American Civilization from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His father had originally introduced him to the Middlesex Canal as a youngster and when he grew up he became a member of the Middlesex Canal Association. So it is rather all in the family that he produced the Corporation’s inventory.

The “Scope and Contents Note” to the register tells us “The records of the Middlesex Canal Corporation are remarkably complete after almost two hundred years. These late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century records include: bills of lading, toll record books, and toll receipts that detail goods transported on the canal; salary checks, bill receipts, ledger books, journals, ledger sheets, orders, and letters that document the financial condition of this experiment in inland navigation, as well as, conditions for canal employees; Board minutes, reports, and letters that detail the problems and policies of an early corporation in Massachusetts; and letters, reports, and diagrams that demonstrate technological innovation.”

The fact that the records that exist are so very complete assures us that they probably cover almost every aspect and detail of the Corporation’s history – and more important for this essay – that here one should find a clue about the Cambridge canals. Unfortunately, an examination of all the listed folders in the inventory shows none marked either “Cambridge” or “Canals in Cambridge.” Nor do the individual names of the various Cambridge canals appear as folder entries – although they do for the several canals in New Hampshire. The result is that there is no good place to start looking for the topic in the collection. Probably the only way one can be absolutely sure that there is nothing here – is to examine every record book and every folder and every sheet of paper in those folders. But there is nothing really to indicate that such a massive undertaking should be or needs to be attempted.

So far the sources we have examined omit the topic of the canals of Cambridge and just how – or if – the Middlesex Canal might have influenced their story. But we turn now to other sources that reveal that more data exists on this topic than has up to now emerged.

Lewis M. Lawrence, a graduate of M.I.T. and an architectural draughtsman for most of his life, late in the 1930s became interested and then addicted (in a good way) to researching the history of the Middlesex Canal. By 1942 he had compiled a carefully prepared manuscript on what he had learned and while he never fully edited it for publication, he did decide to self-published it that year. In 1997 the Middlesex Canal Association had it reprinted.

One of the virtues of his work was that he included in his text extensive quotes from the original records he had examined. Therefore, as regards the Cambridge canals, he found that when the third bridge – commonly known as Canal Bridge or Craigie’s Bridge – between Boston and Cambridge was built and opened in 1809 the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal were involved. The bridge went “from the northwestwardly end of Leverett street, in Boston, to Lechmere’s Point in Cambridge, and Barrett’s Point in Charlestown.”

Lawrence further discovered that the act of the Massachusetts Legislature, which enabled the bridge to be constructed, contained the following two items:

“the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal Corporation shall have full right and lawful authority, to erect, or cause to be erected on either side, or on both sides of such bridge --- all such locks, and other works --- for the conducting the boats, rafts, and floats of said proprietors, or others, using said canal, by the sides of said bridge and causeway --- free from all toll and charge.”

And “the said proprietors of the Middlesex Canal be, and they hereby are authorized and empowered to erect such dam, or other works, northwardly of the line drawn from said Lechmere’s point, and westwardly of said bridge and causeway, as may be necessary and proper, for retaining the water for the boats of said canal to pass on.”

Another legislature act – that of February 26, 1808 – further provided that “the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal Corporation shall have a right --- to cut and make a canal and towing path, between the water in Miller’s River, (so called,) and the waters of Charles River, across the land at Lechmere’s Point, so as to connect with any towing path they may hereafter make on either side of any such bridge.”

The fact that the Proprietors were considering this method – and what is more significant getting the legal right to do so - for allowing the goods transported on its boats and rafts to reach Boston via a towing-path is fascinating. But fascinating and/or speculative ideas that might have developed are just that. In the end what actually happened is the historical fact – and in this case the Proprietors chose to have their boats reach the port of Boston using buoys, anchors, iron rings, and ropes.

What is also of interest here is that the Proprietors were clearly interested in a connection in Boston for their Canal and New Hampshire business – for that was where they expected their business to be. Indeed, in 1808 as Lawrence noted, “a part of the Alms-house wharf, in Boston, was hired and a landing place established.” Further, “a small store or office was erected, and ways constructed for the convenient loading of boats.” Clearly goods from surrounding areas through which the canal did not run could be shipped to this landing spot in Boston – or to Charlestown directly – by wagon or using the immediate Massachusetts coastline - or the Charles River for transporting up or down the Canal. Maybe even by small canals. And there probably must have been some traffic that way.

It is interesting also to ponder the idea that if the Canal’s shipping could have gone direct to Boston using in someway the Canal Bridge the effect that would have had on the Charlestown millpond as the final ending of the Canal. Might it not have resulted into turning the stop there into just another of the Canal’s several landings places?

Now one last comment concerning the Lawrence publication is also necessary here. A search of the index he prepared for his manuscript and reading his text itself revealed no other evidence than what has been stated as to the canals of Cambridge and the Middlesex.

In Sophia S. Simpson’s brief history of East Cambridge one finds early evidence of canals in that area of the town. She wrote “In 1804, a large quantity of land was sold for house lots. Until this time, the settlement had been confined to one street. Streets were now opened and made in all directions. Canals were cut of a sufficient depth for coasting vessels, and more than a mile in length, to communicate with Charles River; and wharves were built on the margin, for their accommodation.” 4 But that is all in this source there is about canals in Cambridge. It is also important to note how relatively under developed and populated this area was during the early – and most successful operational years - of the Middlesex Canal.

Before looking at the – for now at least – definite modern study of East Cambridge, a word about the Cambridge Wharf Company whose name seems suggestive to the purpose of this study. Alas, it was not as this summary quotation revealed. “The incorporation of the city and the projection of the railroad, promising a new era of prosperity and growth, encouraged certain merchants, in 1847, to undertake the improvement of the overflowed lands in this quarter. [Overflowed at this time because the Charles River was still a tidal river.] Corporate powers were secured by them from the General Court, with authority to buy and develop lands between the highlands of East Cambridge and the River Charles and north of West Boston Bridge; and the Cambridge Wharf Company was organized. Beyond the purchase of a tract along the river and the conception of a plan of improvement, this company did little, and finally released its entire holdings to an individual purchaser in 1890.” 5

In 1977 the Cambridge Historical Commission published five carefully prepared architectural history surveys about the city. The one for East Cambridge – first issued in 1965 – was later put out in a revised edition in 1988. The revision was under the direction and supervision of Susan E. Maycock, a reliable and well-known architectural historian.

The study starts with an overall assessment of the development of East Cambridge. Before the start of the nineteenth century few individuals called this area their home. Then appeared Andrew Craigie – termed kindly - and I do mean kindly - in this survey – “an accomplished land speculator” who “obtained a charter for a bridge to Boston” and who further was able to charm “some of the most powerful men in the commonwealth to carry out his plans.” The result was that East Cambridge because of “its proximity to Boston rivaled that of Cambridgeport, Charlestown, and South Boston, and its superior access to water, highway, and rail transportation attracted some of the largest industrial enterprises of the time.” 6 Note the word “water” – but also no any mention of canals or the Middlesex canal in this summary statement.

All sources agree that Andrew Craigie and his business activities is the link between the development of East Cambridge during the first decades of the nineteenth century and the Middlesex Canal’s prime decades of operation. It should also be kept in mind that Craigie was one of the Directors of the Middlesex Canal Corporation.

“In 1793,” Maycock’s volume states, “Craigie became involved in the Middlesex Canal, which was projected to connect the Merrimack River at Chelmsford with Boston harbor by way of the canal’s terminus at the millpond at Charlestown, across the Miller’s river basin from Lechmere’s Point.” As the canal was being constructed Craigie was busy acquiring land in East Cambridge. One of his goals was to build a bridge between East Cambridge and Boston and “the completion of the Middlesex Canal on December 31, 1803, lent credibility to his own bridge project.” Further aiding his project was the fact that Congress made “the town or landing place of Cambridge” along with Boston and Charlestown “a U.S. port of delivery” in 1805. As a result, the future for his bridge looked bright.

Others, however, were also interested in building a bridge here – and one of these parties was the Middlesex Canal Corporation. In the end, although reluctantly, the Middlesex Canal Corporation along with the Newburyport Turnpike Proprietors joined Craigie’s Proprietors of the Canal Bridge to construct just the one bridge. Each of the parties was to own one-third of the projected bridge. The engineer to plan the structure was – surprise, surprise, Loammi Baldwin. The plans he drew, unfortunately, have not survived.

The General Court voted Craigie and his Proprietors a charter for permission to build the bridge in 1807. It stated, “that the toll bridge would serve the public interest by providing access to Boston from the Middlesex Canal and the Newburyport Turnpike, both of which terminated on Charlestown Neck at what is now Sullivan Square. The charter divided the shares in the new bridge equally among Andrew Craigie, the Middlesex Canal Corporation, and the Newburyport Turnpike Corporation, and required the companies to build roads or canals to the bridge.”

In 1808 the General Court amended the charter giving permission to the Middlesex Canal Proprietors “to cut a canal and towpath across Lechmere’s Point to link the Miller’s and Charles rivers.” Finally, after many controversies and legal conflicts the Craigie’s projected bridge was opened in December 1809.

The bridge has been described as follows: “The original length of the bridge was about 2,800 feet, but prior to 1834 a large portion of the bridge at the Cambridge end, about 1,150 feet in length, was removed and filled solid to form a part of Bridge Street. Leverett Street on the Boston side was also extended about 400 feet to the present harbor line. The toll house stood on the northerly side of the bridge about 400 feet easterly of Prison Point Street. Together with several other bridges it was purchased by the Hancock Free Bridge Corporation in 1846 and in 1858 it was made a free bridge. In 1910 the entire bridge was removed and replaced by the solid embankment of the Charles River Dam as a part of the Metropolitan Park System.” 7

There is in this description no mention of towpaths. In Maycock’s study there is also no mention “that towpaths may have been built along sides of this bridge” as Bill Gerber has suggested but he may have another source for his statement. Perhaps there would have been some – because the Middlesex Canal Corporation had been granted the right to construct towpaths here – but when they opted to go with buoys and ropes there no longer was a reason to build any towpaths beside Mr. Craigie’s Bridge. And so it is not surprising there were none.

Just as significant to our story was the action of Congress in 1805 declaring that the ports of Cambridge, Charlestown, and Boston as being in the same district. As a result business leaders in Cambridgeport “had developed a system of canals to accommodate coastal shipping and Middlesex canal boats.” The main links allowing this to take place were the Broad Canal and the North Canal. “The concept,” Maycock states, “must have seen sound: by a network of branch canals, all of East Cambridge and Cambridgeport could be linked through the Middlesex Canal to the commerce of the Merrimack Valley . . . However, Cambridgeport lacked any sort of natural power for manufacturing, its marshes required extensive filling, and its wharves were inconvenient because of the tides. Almost all commerce ceased during the Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812, and the canals never fulfilled the expectations of their promoters. East Cambridge, with better access to Boston Harbor and wharf sites that initially required little filling, was more advantageously located.” 8

Just two other observations from the East Cambridge study by Maycock. The first concluded that most of the goods that “waterborne traffic” brought to East Cambridge “were primarily coal from Baltimore and Norfolk, sugar from the Caribbean, lumber from Maine and the Maritimes, and granite from Cape Ann and the Maine coast.” Note that while the Middlesex also had cargoes of lumber and granite – Cambridge did not usually receive lumber and granite from the areas that produced it that utilized the Middlesex to send it to the Boston area.

As for the Middlesex Canal and at least two of the Cambridge Canals – the North Canal and the Broad Canal – their construction and use “may have been intended to provide a protected route to the canals in the Lower Port.” However, as the Maycock study concluded “Although one traveler tells of going to East Cambridge to board the packet boat General Sullivan for Chelmsford, there is only circumstantial evidence linking commercial traffic on the Middlesex Canal to the Cambridgeport Canal system.” And really it would seem very little circumstantial evidence at that. 9

There we have the story of the canals of Cambridge and the Middlesex Canal – at least until further resources are identified. What do the historical facts tell us? They affirm that the Middlesex was one of a series of canals – but obviously the main one – that made possible commercial and passenger travel between Boston, the Merrimack region of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and probably at least southern Vermont. Stagecoach routes to those locations could have and probably did enlarge the area served. The historical facts also affirm that there were canals in Cambridge that could have facilitated – and probably sometimes did – a connection between the Cambridge canals and the Middlesex. Lastly the historical facts indicate that in reality –and as the records and scholarly research suggest – that connection was at best a minor and tenuous one.

Clearly, then, the chief focus on the Middlesex Canal was Boston and the inland areas of the Merrimack Valley and New Hampshire while the chief focus for the Cambridge canals was Boston and the eastern Atlantic coastal communities. That is all we can conclude now. But historical facts and understanding are always subject to new wine in old bottles – as the concept emerging today called Atlantic History is proving once again. So the way we look at the Middlesex Canal today may be quite different in the future – a fact worth keeping in mind when one seeks to understand the past of Homo sapiens institutions.

Footnotes:

1 Bill Gerber, “Transportation Canals of Eastern Mass And South Central NH A Different Perspective,” Towpath Topics 46 (September 2007) 13. See also his “Middlesex Canal Facts (assembled by Bill Gerber, MCA Board),” in the April 2005 issue of Towpath Topics.

2 For a brief survey of his life see Ernest Cassara, “Lucius Paige,” in the on-line Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography

3 Lucius R. Paige, History of Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1630-1877 (Boston, 1877).

4 Simpson, Sophia Shuttleworth, Two Hundred Years Ago; or, A Brief History of Cambridgeport and East Cambridge (Boston, 1859) 43.

5 Arthur Gilman, ed., The Cambridge of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Six (Cambridge, 1896) 109

6 Susan E. Maycock, East Cambridge: Survey of Architectural History in Cambridge (Cambridge 1988) 1.

7 Lewis Morey Hastings, “The Streets of Cambridge Some Account of Their Origin and History,” Cambridge Historical Society Proceedings for the Year 1919 14 (Cambridge, 1926) 56

8 Susan E. Maycock, East Cambridge 15-29. All the quotations are from this section of the book, which relate in more details than outlined here, the complicated story of Mr. Craigie!s Cambridge business adventures.

9 Ibid., 70-1.

LIFE ON THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

BY ALAN SEABURG

BOOK REVIEW BY TRACI JANSEN

Alan Seaburg was born in Medford - not far from the Branch Canal - and grew up there, went to the Medford schools - and then to Tufts. In 1980 with his brother Carl he wrote for the Medford Historical Society - and for their fellow citizens - Medford on the Mystic - an illustrated history of the community as a part of the 350th anniversary of the founding of the city. This led to their writing with Tom Dahill The Incredible Ditch - the Bicentennial History of the Middlesex Canal. Seaburg’s most recent publication, Life on the Middlesex Canal, offers a new, social perspective of the subject.

Life on the Middlesex Canal is about the “Golden Age” – 1803-1835 – of the Middlesex Canal. Seaburg makes it clear that the intent of the book is not to provide a history of the canal or an engineering study of its construction, but rather, to supplement existing studies with more attention to certain aspects of the canal’s story. The author uses a collection of six essays to portray the human side of canal life.

In Life on the Middlesex Canal, Seaburg possesses a charming writing style. He connects with the reader as well as his subject in a casual, convincing way that that makes us believe he is a friend. Within the text of the essays, we are sent off to the pages of other articles and publications in search of an illustration or a chapter that further explains one of his points. I found myself with a lap full of open books cross checking and completely captivated. I appreciate the inclusion of the author’s worldly perspective on canal life and life in general. All of the essays are well researched, using detailed footnotes to credit original sources and Seaburg includes poetry and song to portray a cheerful time in history. Tom Dahill’s extraordinary cover and familiar sketches offer a glimpse into the past and help us imagine life as it was back then.

One essay, “The Canal, the Master-Builder, and the Bulfinch Building of the Massachusetts General Hospital” describes Boston’s desire for a public hospital. In the essay we learn how the MGH Trustees, after studying several building designs, chose their Master-Builder, Charles Bulfinch. The essay includes a great deal of information about the use of Chelmsford granite as well as the methods of transportation and working of the stone for the MGH building and many others in Boston. The author invokes feelings of pride and perseverance in the reader as he invites us to “remember, then, the next time you are at MGH as you approach the Bulfinch Building/Pavilion the laborers who quarried the Chelmsford granite, those who loaded the stone for Charlestown onto the boats that plied the Middlesex Canal, the convicts who hammered and cut it into useable blocks, and finally the men who used them to construct the first building of one of America’s greatest hospitals. And please salute them all!”

As an elementary school teacher, I incorporate the Middlesex Canal into the social studies curriculum for third graders. The Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks in History require that third graders learn about Colonization of America, the American Revolution, and state and local history. Third graders learn of an independent America that was no longer limited to trade with England and sought to open up the vast interior of New England for the purpose of transporting goods. The subject comes to life when students visit the remains of the Shawsheen and Maple Meadow Brook Aqueducts which are right in our own back yard. I believe that Life on the Middlesex Canal has a place in the elementary classroom as a supplement to the existing Middlesex Canal curriculum. The essay “Fun and Games at Lake Innitou” describes the recreation of the Horn Pond resort and students can easily compare life today with life of earlier inhabitants such as the members of “the Massachusetts,” the first English colonists, and the passengers who visited on Middlesex Canal boats.

Another essay, “Your Passport, Please” answers the question of what kinds of goods were transported on the old Middlesex Canal? Seaburg explains that the “Golden Age” of the commercial life of the canal was a time marked with hope and promise for New England as the “population was growing rapidly, towns were being built, water power was being developed and utilized, old factories were being enlarged and new factories founded.” Life on the Middlesex Canal helps students understand the idea of an improving America. The book could be used as an integral part of a high school history curriculum as students could read for themselves the social and historical significance of the “Golden Age” of the Middlesex Canal and the impact it had on our country’s progress.

The final essay in the collection is an account of the first Middlesex Canal Museum. “We Just Had So Much Fun” tells the story of the founding of the Middlesex Canal Association in and the efforts of those local folks to establish a museum “devoted to the history of said canal and of transportation in general.” Through news items and interviews Seaburg recounts the story and the reader can feel the enthusiasm of those involved. While it is true that the story of the first canal museum is complete and part of the past, I wanted the author to bring the subject of the Museum into the present and to share with the general reader all of the fun we’re having today with the new Middlesex Canal Museum. But perhaps it is too early to tell the story of 71 Faulkner Street. The closing theme of Life on the Middlesex Canal, “We Just Had So Much Fun” clearly connects the two museums and connects our past and present to the future.

Contact Alan Seaburg, 4 Riverhurst Road, Unit 207, Billerica, Massachusetts 01821 to obtain a copy of Life on the Middlesex Canal. Checks must be made out to Alan Seaburg for the amount of $16, which includes shipping expenses and any other appropriate charges such as sales tax. The book should also be available through the Middlesex Canal Museum store.

FOLKLORE AND MUSIC OF THE RIVERS AND CANALS

by Bill Gerber

Although American folklore is fairly rich with music and stories from the canal era, that which is specific to New England’s canals is not plentiful. What follows is an assemblage of the little that has been found to date.

Lyrics are known for at least one tune that seems to be unique to the Merrimack River and Middlesex Canals. Presented immediately below, this one almost certainly originated as a work or tavern song, sung by boatmen from the village of Derryfield, New Hampshire. (The name, Derryfield, NH, was changed to Manchester in 1810. 1)

ONE MORE STROKE FOR OLD DERRYFIELD

|

Planks and shingles we carry down Threading river, canal and locks; Set your pole in the river’s bed; Shoulders braced ‘till the stout pole bends |

Four days downward, five days back -- See the lights of the jolly inn -- Life is joyous, both up and down. Always pushing the cargo through, |

Regrettably, the musical score is not known. Perhaps it could be reconstituted by a good musicologist.

Mill Creek refers to the canal by that name that bisected Boston; extending along Canal Street from what is now Causeway Street to Haymarket Square, and out the creek itself into Boston Harbor.

The tune is mildly revealing of canal operations. It identifies some of the cargos brought down, as well as those taken on the return trip. It also makes reference to riding the Merrimack River current down from Derryfield (four days down), but fighting the same current on the return by poling the boats upstream (five days back). Poling was exhausting work, hence its mention thrice in the tune. On the water, songs like this may have served both to coordinate the boatmen’s’ efforts and to keep up their spirits.

Unlike other canals, where whole families lived aboard their boats, in this area, normally, only men worked the boats, thus there were taverns, enlarged lock tenders’ houses and other facilities to feed and shelter the boatmen and other travelers.

Next, there are words, characterized as a poem, which is a post canal era lament. Presented below, was it ever set to music? Probably not, but it would be interesting to see what a good musicologist might make of it too.

THE RIVER MEN

In damp of rising river mist, Mine host, Old Moses Eddy, I don’t put up with drunkards here, “Why, bless your heart, my dear man, The fireplace was roarin’ |

A giant black from Hayti stood The talk was coarse and raucous Black-strap and flip and Medford ran, But as the streaks of mornin’ dawned, I listen at the landing place, |

Though it echos the role of the setting pole, the poem doesn’t have much to say about travel on the river and its canals, but it gives a modicum of insight into how the boatmen spent evenings in the taverns.

FIGURE 2. RIDDLE’S TAVERN, NOW BUCKLEY’S STEAKHOUSE

At least one such river tavern has survived and continues to serve a hospitality role, though today it attracts a somewhat different clientele. Pictured in figure 2, it was built by Isaac Riddle in 1802, and thus served boatmen for more than a decade before the Merrimack River canals were constructed. Today it is a restaurant located along Route 3, on the north side of the town of Merrimack, NH, north west of the confluence of the Souhegan and Merrimack Rivers. No doubt the level of the cuisine served has been upscaled somewhat since canal days.

THROUGH THE MIDDLESEX CANAL 2

In the summer of 1829 Samuel Jones Tuck and his, wife Judith took a three months’ trip through New England, going, of course, by canal and carriage, this being before the days of railroads. Mrs. Tuck wrote a rhyming diary of the trip, which was printed in the Nantucket Inquirer and Mirror soon after.

The trip began by a ride through the Middlesex Canal, and the portion of the diary telling of this is given here:

|

I Sunday the twenty-fifth of June At 8 o’clock we went to the boat Now as I sat there at my ease The scene it is so very fine Oh how delightful is the scene, I ne’er before a Lock did see |

II It is a great curiosity indeed Over us now dressed are the willow trees How can we view these beauties dear If any one would wish to walk It took them more than half an hour We sat down on the grass so sweet, |

|

III Surrounded by green fields and wood Now by this time, they had got through; We reached the head of the Canal And then for Lowell took our route, There we found our friends all well Next day we had delightful showers Oh how romantic is the scene Oh how delightful is the scene |

IV And many things that here we see On Monday Morn we took a walk Some of the rooms were very neat Now as we were returning back The Bell it had rung seven o’clock, One thousand men they say are there |

In the passage that begins “When we had reached to Woburn town”, Mrs. Tucks tells of the ascent through the three two-lock staircases above Horn Pond. Apparently their Packet arrived there around noon time “The Sun being o’er the Meridian Line”, and it took the boatmen “more than half an hour” to negotiate the six locks. This time, then, averages to about five or six minutes per lock, maybe a little longer, which is pretty quick even for a tended lock. This would also represent about the best achievable time-to-ascend since the Packet had priority over both luggage boats and log rafts.

And while the boat was working through the locks, the passengers disembarked, strolled and had a short lunch. Apparently, on this trip, the passengers did not dine at the Horn Pond House, as early packet trips did, Mrs. Tuck states that “ each one carried his own fare”.

She goes on to state that they arrived in Chelmsford a little after three in the afternoon, reaching Lowell around four. This is consistent with such trips made after the Boston-Lowell Rail Road was completed in 1835, but it’s a little surprising to see that seven hour trips were being made as early as 1829. When the canal first opened, and for some years thereafter, trip times of 12 and 18 hours seem to have been the norm, but these seem to have stopped at a tavern en route for at least one meal.

___________

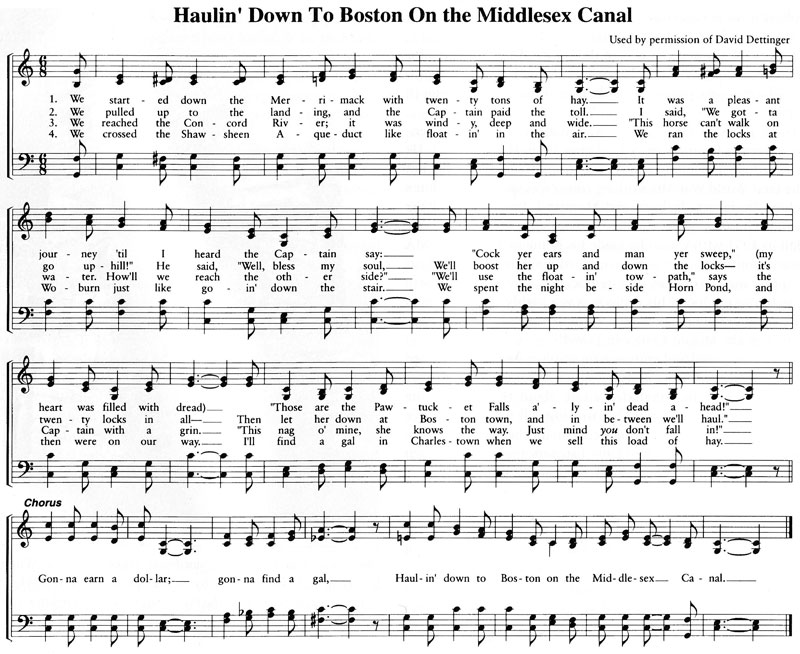

As was done for the Erie Canal, a popular tune was also written for the Middlesex. Of more recent vintage and not quite so well known as that for the Erie, the Middlesex Canal’s tune is titled “Haulin’ down to Boston”. It was written by our own (MCA member) Dave Dettinger as part of the several theatrical creations he wrote and choreographed to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Middlesex.

The Erie’s tune is the well known: “Low Bridge, Everybody Down”; sometimes also known by the first line of the refrain. Written in 1905 by Natick, Massachusetts, born Thomas Allen, this Tin Pan Alley tune was a lament to the replacement of mules by engines to power canal boats; most boats were motorized by the time of World War I. 3

The lyrics, in many verses, describe the long trip between Albany and Buffalo NY. Two verses are presented below; additional lyrics can be found at various internet sites and other sources.

LOW BRIDGE, EVERYBODY DOWN

I’ve got a mule, and her name is Sal, fifteen years on the Erie Canal. Chorus: We’d better look for a job, ol’ gal, fifteen years on the Erie

Canal! |

The score and lyrics of Dave’s tune for the Middlesex Canal are as shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Dave Dettinger’s “Haulin’ Down to Boston … .”

The (Middlesex -- E-ri-e) Canal

There is reason to believe that another tune, much better known to Erie Canal aficionados, may have been “borrowed” from the Middlesex Canal; the oral tradition claims so, and some of the words “just fit better”. Conceivably, the tune may have been carried off to New York in 1817, the year construction was begun on the Erie Canal. In the summer of that year, and perhaps the previous one, a group of New York Canal Commissioners visited New England to learn what they could about the engineering, construction and operation of the Middlesex and Merrimack River Canals.

Of course, we don’t know if this tune is original to the Middlesex; or if it, in turn, was “borrowed” from yet another canal, perhaps an English canal (reference to “gin” suggests this possibility), or possibly even from New England’s sea faring heritage. The lines of the refrain, with a few key words selectable for either canal, go as follows:

| “Oh the {Middlesex/ E - ri - e} was arising, and the gin was getting low And I scarcely think I’ll get a drink till we get to {Butter’s Row/ Buffalo}.” |

Additional lyrics for this tune, some of which may have been adapted from Middlesex lyrics, are presented below. 4 (The development of lyrics to transform this tune to reflect activity on the Middlesex Canal is left as an exercise for the reader.)

We hollered to the captain When we get to Syracuse The cook she was a grand ol’ girl, The captain, he got married, |

We were forty miles from Albany, The winds began to whistle, We were loaded down with barley, Two miles out from Syracuse |

FAREWELL!

In 1853, as the Middlesex Canal was being “drawn off” - that is, closing down - the following poem was penned by someone who styled themselves “I l’imoon”. It appeared in the Woburn Journal, Oct. 23,1853.

OUR OLD CANAL

Thou old canal! thou old canal! No more upon thy banks shall grow, The flowerets, too, no more shall spring, Full many a year thy waters flowed, Thy shelving basins, once so fair, |

But desolation sere and dread, The Scots may sing of Avon dear, Thou wert an Avon then to me, Thou old canal! thou old canal! Upon thy banks fond lovers now, |

Footnotes:

1 Perkins, David L; Old Derryfield and Young Manchester; Manchester Historic Association Collections, Volume 1, 1896-1899; p. 95

2 Historical Register, Vol. XXXVI No. 3, Sept. 1933; Medford Historical Society, Medford, Mass. pp-42-44

3 Palmer, Richard; “Erie Canal has always been a musical waterway”; http://www.nycanaltimes.com/pages/articledetailsarch.asp?cat=67&art=525&iss=6

4 Traditional Sea Shanties & Sea Songs; http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/sea-shanty/Erie_Canal.htm

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

Did the canal system ever played a part in the ‘Underground Railroad’, the system established to assist southern negros to escape from slavery? One reference to such a role was noted in “Traces of the Trade; A Story from the Deep North”, a study presented by Katrina Brown, whose Rhode Island ancestors may have been the largest slave-trading family in the early USA. This was an ad for a runaway slave that read:

“Runaway from on board the canal boat ‘Iron Sides’, owned by Augustus Marshall, lying at the wharf of Mr. Woods in Boston. A man by the name of Rewel Cory, about 26 years of age, black hare, black whiskers, a long beard.”

Are readers aware of any items of folklore or music? If so, please contact me (Bill Gerber) at 978-251-4971 or <wegerber at verizon dot net>.

FUNCTION ROOM RENTAL

For the past seven years a group of dedicated volunteers has operated the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitor Center at the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica. Throughout this time, the generosity of the owner allowed us to stay there rent free. However, he now feels it essential to charge us rent.

We do have good facilities for rental in a charming Museum. Should you plan a function, we hope that you will consider us. A very reasonable charge of $200 covers the room and a committee member who will be present throughout to assist you. For more information phone 978-670-2740; leave a message and someone will return your call.

MASTHEAD

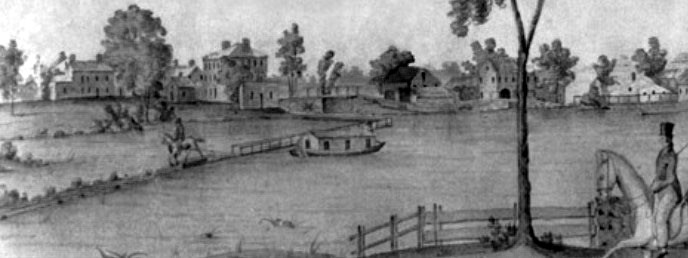

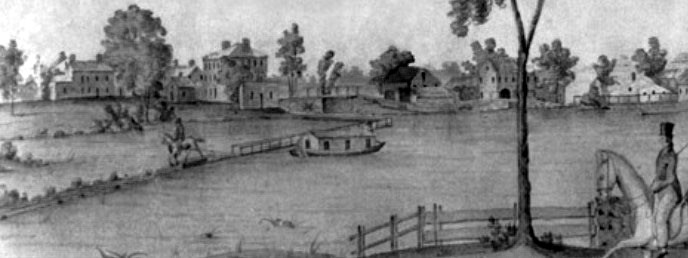

An excerpt from a watercolor painted by Jabez Ward Barton, ca. 1825, entitled View from William Rogers House. Shown, looking west, is a packet boat, possibly the George Washington, being towed across the Concord River from the Floating Towpath at North Billerica.

BACK PAGE

An excerpt from an August 1818 drawing of the Steam Towboat Merrimack crossing the original Medford Aqueduct (artist unknown)