Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box

333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

Volume 28, No. 1 September, 1989

26th ANNUAL OLD MIDDLESEX CANAL WALK

Saturday, October 14, 1989 at 1:30 P.M. (rain date: Oct. 15)

Meet at Canal monument in Chelmsford, Riverneck & Canal Roads.

Our annual fall Canal Walk will take place in Chelmsford and Billerica this year. It will follow the tow path of the Canal, beginning at the location now known as the intersection of Riverneck and Canal Roads, but originally called "Manning's Bridge," near the Long Swamp, which continued into Lowell. Our route will take us past our newly acquired 1600-foot easement from UPS and by a well preserved section of the Canal in Billerica. There will be several stops for historical commentary and many opportunities for taking pictures of the fine fall woodland and swamp foliage.

Directions to the Chelmsford Canal monument: From Rte. 3, take the Rte. 129 exit, at the Chelmsford/Billerica town line. Go west on Rte. 129 (Billerica Road) for 1.5 miles, then turn right on Riverneck Road (opposite Prudential Insurance Building). Continue straight for 1 mile, over Rte. 3 and under highway ramps. Immediately after the ramps, park on the left in the paved lot at Techserve Co. Meet at the monument located in front of the other side of the building, on Riverneck Road, opposite Canal Road. From Chelmsford Center, take Rte. 129 (Billerica Road) east about 0.7 mile and turn left on Riverneck Road; continue on that road as above.

For more information, call David Fitch at 508/663-7848.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Please put these events on your calendar. Further information, if required, may be obtained from Fran or Burt VerPlanck at (817)729-2557.

FALL MEETING

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 1989

THE MIDDLESEX CANAL ASSOCIATION will hold its fall meeting at 2 p.m. on Sunday, November 4, at the Patrick Mogan Cultural Center, 40 French Street, Lowell.

Martha Mayo, Curator of Lowell History Special Collections, will talk about our Middlesex Canal Archives in Lowell.

WINTER MEETING

SUNDAY, JANUARY 21, 1990

THE MIDDLESEX CANAL ASSOCIATION will hold its winter meeting at 2 p.m., Sunday, January 21, 1990 at a location still to be determined. Ernie Knight, of Raymond, Maine, will show slides and speak about Maine's Cumberland & Oxford Canal. This Canal ran from Portland through Sebago Lake, Songo River, and Long Lake. The canal boats on this unique waterway had sails for use on the lakes.

An announcement will be mailed to the membership of the MCA in early January to give the location of the meeting.

PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE

We have an interesting year ahead of us, as the program announcements in this bulletin show. This spring's canal walk in Winchester was a success, and on Memorial Day weekend we hosted the bus tour of the entire canal route for our American Canal Society friends. If there's enough interest to cover the costs of a bus, we could arrange a similar end-to-end Canal tour this year.

"Surveying" the whole route in a day really brought home for me what an immense undertaking this canal project was, especially considering the state of the art and science of engineering in the eighteenth century.

Speaking of immense undertakings, Billerica's Historic District Study Committee is proposing a mill district that would include the portions of the canal that adjoin the mill pond on the Concord River. The proposals will go through public hearings this fall and winter.

A recurrent theme for Billerica's study committee is that an historic district is not just about how a place looks now, or how it looked in "history" two hundred years ago; it's about how you want a place to look twenty years from now, or a hundred years.

Best wishes for the fall season,

David Allan Fitch, President

Middlesex Canal Association

AMERICAN CANAL SOCIETY MEETS IN LOWELL

by Bill Gerber

On Memorial Day weekend this past spring, the American Canal Society held its meetings in Lowell. We began Friday evening with a glass lantern slide show of the Middlesex Canal, presented by Fred Lawson. Fred has thoroughly researched the old Middlesex, and has covered about every inch of it on foot, probably several times. His slides were made in the 1930's by Mears. Morrison, Payro, and Cutler, who collaborated respectively to accomplish the maps, paintings, and photography at a time when many remains of the canal were still largely undisturbed. The show was an excellent preview of what we would see the next day.

Next up was Wil Hoxie, who talked about the Middlesex Canal above Lowell. I knew that the canal extended up as far as Concord, New Hampshire, but Wil pointed out that it had gone far beyond that, up to about Plymouth; it had carried goods from as far away as the White Mountains in New Hampshire and White River Junction in Vermont. It was because of this that the Canal didn't fold when the lower section was paralleled by the Boston-Lowell Railroad, nor even when that line was extended up to Nashua. Will's well researched talk was most informative.

On a gloriously bright and sunny Saturday, Dave Fitch, President of the Middlesex Canal Association, with Burt and Fran VerPlanck and Dave Dettinger, guided two busloads of ACS and MCA people along the route of the Middlesex. Burt had prepared a very detailed set of maps to help orient us to various sections of the canal. Considering that the Middlesex closed down about 130 years ago, one would expect that there would be little to see of the canal prism and towpath lock structures and even watered sections, but we saw all of these, walked for considerable distances in and along many of them, and found such features as the tie-point rings for the floating towpath over the Concord River and the abutments and piers of several aqueducts.

At the end of the Middlesex Canal tour, we stopped on the west side of Lowell to see Francis Gate and the upper guard lock of the Pawtucket Canal. The first increment of what became the power canals of Lowell, the Pawtucket opened as a transportation canal in 1796. It was about a quarter of a century old, and largely made obsolete by the Middlesex, when Mr. Lowell and his associates first came to what was then East Chelmsford. Francis Gate, also called "Francis's Folly," is a huge "guillotine" barrier that is normally chained up above the center of the guard lock. It has more than vindicated Mr. Francis by saving Lowell from a number of major floods.

We did the rest of the Pawtucket in pieces: one only needed to look out one's hotel window to see the "staircase" of the lower locks within "spitt'n distance," and Monday's tour covered Swamp Locks and the subsequent power canal spurs.

That evening, attention turned to the Blackstone Canal that extended from Worcester, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. Monica Fairbairn, Project Manager for the Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park in Massachusetts, and Jim Pepper, the National Director, told about the state and national effort to create a linear "Heritage Corridor" park to commemorate this valley that is the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution and to help restore some of its prosperity. The Blackstone Canal is a major focal point of this effort. As the talks and pictures showed, considerable work has already been done and more is planned, but much more remains to be done to make this unique perk a reality.

ACS Life Member and Director Dave Barber worked for months to put the Blackstone Canal tour together, and on Sunday his efforts paid off handsomely! Dave studied all the maps, walked and measured and kept copious notes on all of the canal he could find, cleared towpath, negotiated with landowners for access, and made several trial runs to be certain that everything was in order. As a result, he was able to show us things that even the state and national park people may not know about. There were locks and landings, miles of watered sections, points where the canal clearly entered or exited the river, and even a mile marker still in place where the builders put it 150 or so years ago.

During a stop at Plummer's Landing, a shipping point on the old Canal, we were greeted by representative Dick Moore, an elected member of the Massachusetts Legislature, who stopped by specifically to meet our group. Rep. Moore gave us his first-hand account of the work that has been done to initiate and sustain the Heritage Corridor effort. He was accompanied by Margaret Carroll, and Shirley and Jimmy Cleaves, representatives of the Corridor Commission, who passed among our group, handing out hats, scarves, and packages of information and answering questions wherever they could be found. This was a most impressive show of local interest and support for what is currently happening in the Blackstone Valley.

At about the Massachusetts/Rhode Island border, we broke off and headed over to the Cape Cod Canal. There, Corps of Engineers representatives showed us through the control center that monitors traffic all along this still very active sea-level Canal. Walt Mesek, one of our number, became somewhat excited by the sight of a tugboat, painted colors familiar to him, towing a large barge. Walt was once in the tugboat business, and so a number of us received a bonus description of the history and workings of tugboats.

After Sunday evening dinner, Ruth Hummel, President of the Plainville, Connecticut, Historical Society, presented a slide show and talk about the Northampton - New Haven Canal, also known as the Farmington Canal. Together with Mel Schneidermayer, who was unable to join us, Ruth was personally involved in a successful bicentennial project to restore a section of that Canal and to develop a park around it in Plainville. She described that effort, as well as the color and lore of the Canal and of the people who lived on and along it. Ruth has continued to research the Canal and to assist other communities with their efforts. In retrospect, hers may have been the most important message of the weekend, for she showed just what a few determined people can accomplish in the interest of historic preservation, and the development of civic pride and knowledge of cultural heritage.

A second talk and slide show was presented that evening by Ernie Knight, President of the Cumberland and Oxford Canal Society. The C&O was another major New England canal that we were unable to visit; it ran west out of Portland. Maine, into Sebago Lake and on into Long Lake. Ernie brings more than one lifetime of knowledge to bear on the subject; his father worked on the Canal in his youth and eventually owned two of the "classic C&O" two-masted, drawn/sailed/poled canal boats; also, his grandfather had had much to do with the C&O. Ernie drew from this heritage, as well as from the results of his own long-term efforts to record the history of the C&O, to tell us of its beginnings and its end, and to show some of what remains to be seen. Considering that Ruth Hummel was a "tough act to follow," Ernie Knight rose to the challenge admirably.

We concluded the weekend on Monday morning with a guided tour of the canals of Lowell, conducted by Richard Scott, Park Supervisor for the Lowell Heritage State Park. A "local boy," Rich knows the canals of Lowell very well, and is regarded as one of the foremost "living history" interpreters of the canal and mill era. He was able to show us Swamp Locks on the Pawtucket Canal, and many of the Canal spurs that were extended from it as more and more mills were built in Lowell, and how power was derived from them. As you might expect, his tour was superb. We finished this tour and the weekend at the National Park Service Visitors' Center (Lowell is our first Urban National Park), after which each person was free to pursue his or her own interests.

[Editor's note: Ernie Knight will be presenting his program at the winter meeting of the MCA. See details elsewhere in this issue.]

MALCOLM CHOATE HONORED AT HARVARD

On May 8, 1989, the Middlesex Canal association presented a copy of Mary Stetson Clarke's book "The Old Middlesex Canal" to the Harvard University Library to honor the memory of our late founding proprietor, long-time treasurer, and good friend, Malcolm Choate (Harvard '34). The ceremony was held at Pussy Library, and was attended by MCA President David Fitch, Edith Choate, Mary Stetson Clarke, Louis Eno, and Wilbar Hoxie, as well as Harley Holden, Librarian at Harvard's Pussy Library, who received the book for that institution. The remarks that follow, on p.7, were delivered by Louis Eno, after which MCA Director Edith Choate presented the book to Harvard in memory of her late husband.

Presentation of "The Old Middlesex Canal" to Harvard University in memory of Malcolm Choate. From the left: MCA President David Fitch,

Edith Choate, Louis Eno, Harvard Librarian Harley Holden, Mary Stetson Clarke and Wilber Hoxie.

REMARKS AT PRESENTATION OF BOOK TO HARVARD LIBRARY

IN MEMORY OF MALCOLM CHOATE

It is a great pleasure for me to be back here again. It feels like Old Home Week or Class Reunion: old friends from the Middlesex Canal Association, old friend the Archivist, and next door to Widener where, forty years ago, I was in charge of the main reading room two nights a week.

We are here today to present a gift to the Harvard College Library in memory of Malcolm Choate of the class of 1934.

I knew and worked with Malcolm for many years. From what I could see and hear, his three main outside interests were the Class of '34, the AMC and the Middlesex Canal Association. I would call the combination of these three Malcolm's triad - with apologies to him for using Department of Defense jargon.

Like so many of us, he was fascinated by the story of the Middlesex Canal: an early 19th century business enterprise, started by sons of Harvard, an important contributor to the advancement of engineering science, a participant in the development of the industrial revolution in Lowell, and a precursor of the Erie Canal.

For many years, two legs of Malcolm's triad of interests converged when he set up, coordinated, and ran annual canal walks for AMC and MCA members. I participated in these walks for many years, but all I had to do was to walk and talk. Malcolm had to get the Boy Scouts to clear the towpath, write up the press releases, announce the event in the AMC bulletin (which always seemed to have a very early deadline), get newspaper publicity - and worry about the logistics of getting people back to their cars after the walk. All of these he did extremely well - we always had a great crowd of walkers and we never lost one of them.

Today, we are here to connect the third leg of Malcolm's triad with the other two, by presenting a book to his alma mater in his memory.

The book is an important one - it is now the classic story of the Middlesex Canal, since the University Press has let its own history of the Canal go out of print. But more than classic, Mary Clarke's story of the Canal is timely and up-to-date, retelling the fascinating story in a way to stimulate the reader's interest. It is also a guide-book and it is illustrated! You all remember the old French proverb: A book without pictures is like a day without sunshine.

And so, it is a great pleasure for the Middlesex Canal Association to present to the Harvard College Library an autographed copy of Mary Stetson Clarke's "The Old Middlesex Canal," in memory of its long-time Proprietor, Director, Treasurer and friend - Malcolm Choate.

And now I would ask Edith Choate to make the presentation. Thank you.

| May 8, 1989 | Arthur L. Eno, Jr. |

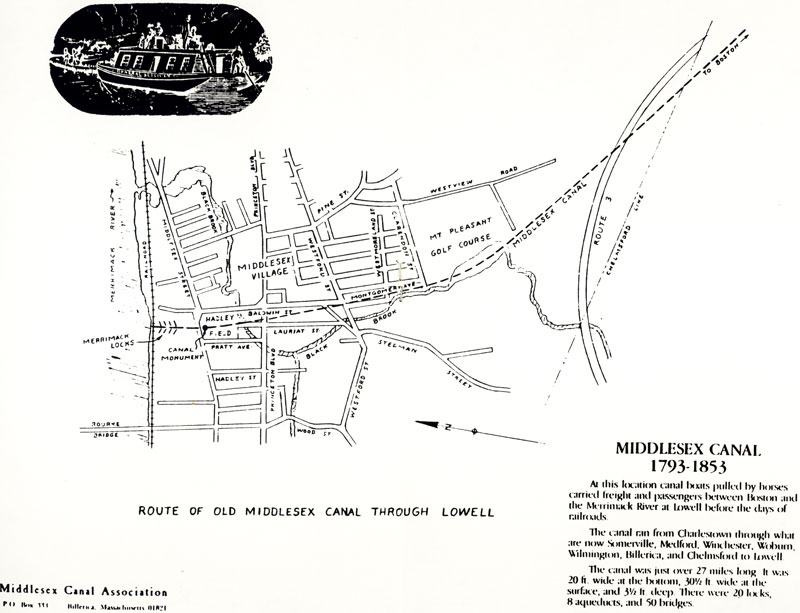

MIDDLESEX CANAL

1793-1853

At this location canal boats pulled by horses carried freight and passengers between Boston and the Merrimack River at Lowell before the days of railroads.

The canal ran from Charlestown through what are now Somerville, Medford, Winchester, Woburn, Wilmington, Billerica, and Chelmsford to Lowell.

The canal was just over 27 miles long. It was 20 ft. wide at the bottom, 30½ ft. wide at the surface, and 3½ ft. deep. There were 20 locks, 8 aqueducts, and 50 bridges.

CANALS OF BRITAIN - HISTORY AND RESTORATION

by Jeremy Frankel

Just over two years ago (October 15, 1987, to be precise) I landed in America to begin yet another chapter in my involvement with canals. Ever since that fateful first vacation back in 1974, I had spent most of my spare time either on friends' narrow boats, renting boats, or restoring long forgotten derelict waterways. I also sat on several committees raising money for one canal cause or another. Somehow since that time I had managed to navigate most of England's 2500-mile canal network, and through a friend who owned a small barge in France I had also traveled the canals in Belgium, France, The Netherlands, and Switzerland. Now I was in New York poised on the edge of my latest venture: a four-and-a-half month journey, mostly by Greyhound bus, to explore some of America's waterways, from those long-forgotten and buried nineteenth century ditches to the largest modern waterways that American engineers could build.

I was, in no small way, aided and abetted by many canal buffs around the country. Without their expert knowledge, assistance, and hospitality, my trip would not have been possible. Between October 1987 and February 1988, I visited 23 states, saw 43 canals, and recorded it all on 55 rolls of film. The only way I could repay my various hosts was by presenting slide shows, the sort of thing I did in England, explaining how one of the organizations I belonged to restored derelict waterways.

Because of my itinerary (United States, Canada, Mexico, and Panama), it was a little difficult tracking my whereabouts. But somehow David Fitch managed it, buttonholing me at my cousin's in Montgomery, Alabama, a week before Christmas. We made tentative plans and arrangements for me to talk to the Middlesex Canal Association; this I was to confirm by telephone when I got back to New York sometime towards the end of January. It was with some amazement to David and myself that I actually turned up on the "penciled-in" date of Saturday, February 6, 1988.

On the following day, with snow lying everywhere and in trepidation of the turnout, as I entered the Church Center in Chelmsford I was greeted by the sight and sound of over 100 people. I quickly realized that this would be the largest group of people I had so far lectured to in the United States.

The illustrated lecture followed the usual format of the kind I gave in England. It was divided into two sections. The first half showed in a detailed and thorough manner the technology of canals: the locks, aqueducts, tunnels and embankments. The main thrust of the talk was not of how canals began, a topic that had been fairly well exhausted, but the diversity of engineering skills employed to tackle the ever-changing terrain. For it was the development of canals that gave rise to the birth of modern civil engineering.

In the 60 years of the canal age, beginning in 1759 when the Duke of Bridgewater opened the Bridgewater Canal from his coal mine at Worsley to Manchester and ending with the building of the Shropshire Union Canal, lay the foundation of civil engineering. Brindley, the engineer for the Bridgewater Canal, followed a circuitous 87-foot contour from Worsley to Manchester, thereby eliminating the necessity of building any locks. The Oxford Canal meandered nearly as badly, but accepted the need for a couple of dozen locks in order to lift itself out of the Thames valley onto the midlands plain. But, not far from the Oxford's junction with the Grand Union Canal, the latter had a flight of 21 locks to climb up the hillside near Warwick.

Aqueducts began in pretty much the same way, almost an apology for crossing some river. But, as engineers became more skillful, so their skill became reflected in the architecture and scale of the structure. Thomas Telford, the founder of the Royal Institution of Civil Engineers, built the finest aqueduct of them all. In northern Wales, over the valley of the river Dee, lies an aqueduct just over 1000 feet long (not to mention its approach embankments of another 1000 feet), and 121 feet high, with 21 pillars striding across the magnificent terrain. All this just to carry a seven-foot wide cast-iron trough of the Llangollen Canal over the river at Pontycysyllte, a place almost as unpronounceable as it is unforgettable when one travels across it.

These sixty years that paralleled the English industrial revolution were time enough for the new art of civil engineering to be practiced. Mistakes were made, ideas had to be rethought, and structures didn't always stay up, usually resulting in the tragic loss of life. But by the 1820's, techniques had for the most part been worked out successfully. In fact, the new civil engineering was sufficiently successful that with the experiments with steam traction also taking place at the beginning of the nineteenth century, engineers were able to build the railroads for these steam locomotives with comparable ease. The results of learning the skills of civil engineering by the slog of the last sixty years in the mud of the canals was handed to railroad engineers 'on a plate.' Where the Huddersfield Narrow Canal had penetrated the Pennine Hills with a three-and-a-half-mile long tunnel which took fifteen years to build, an adjacent railroad tunnel took only four years. Not content with borrowing the construction techniques, the railroad builders also followed the same routes, parallel to the canals down in the valleys, whilst their viaducts mirrored and overshadowed the aqueducts as at Chirk on the Llangollen or at Marple on the Macclesfield. Within fifty years, railroad companies reigned supreme, buying out canal companies which could not compete and then reducing the latter's maintenance until the canals collapsed and fell into dereliction.

Out of 3500 miles of rivers and canals, a 2500-mile network remained, more or less intact. About 1000 miles lay buried in the undergrowth of woods, being used for drainage in the countryside, or in towns, used to dump unwanted garbage - the unofficial community rubbish dump. At the end of the Second World War, at the instigation of half a dozen like-minded individuals, the Inland Waterways Association (INA) was formed. Throughout the 1950's and early 1960's, the relationship between the small canal societies now springing up and the INA on the one hand, against the national navigation authority on canals - the British Waterways Board, was one of antagonism. Because of this and petty politics, there was little success towards restoring any of the disused canals. In 1968, the Transport Act was passed; this divided up the existing network into commercial, cruising, and remainder waterways. No account was to be taken of the 1000 miles of derelict canals other than that they were decreed to be officially abandoned. Some local authorities began in-filling them and burying them under new housing estates or building highways over them, ensuring that they could never be restored.

But, as we say in canal parlance, "things were stirring in the mud." In about 1968, a young man by the name of Graham Palmer became so fed up with the petty politics that he literally threw some shovels into his car and, with a couple of friends, drove from London to Stourbridge, just south of Birmingham. There some people, in open defiance of British Waterways Board, the law, etc,. were attempting to keep a canal open. The weeks and months rolled by, and Graham began producing a small broadsheet called "Navvies Notebook." This listed all the canal societies, their working party organizers, and the dates of the forthcoming working weekends.

The late 1960's saw the slow transformation from antagonism to cooperation. Graham's organization, now known as the Waterway Recovery Group, began to grow. With fund-raising and donations, WRG began to acquire backhoe excavators, dump trucks, generators, water pumps, and scaffolding, not to mention hundreds of picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows. All this equipment was loaned to the canal societies on an expenses-paid basis. WRG had its own subdivisions of restoration groups. Most groups concentrated on just one canal, supplementing another canal society. Others, like the London Group, were "mobile," regularly visiting four or five canals, going away once a month. The growing skill of WRG was proven by the occasional public relations exercises or "big digs," as we called them. Probably the most famous and significant was held in 1969 at a canal junction near Manchester. An article and request for help in "Navvies" (now a shorter name but running to twenty pages) produced the astounding turnout of 1000 volunteers who had to be found sufficient work, equipment, food, and somewhere to stay for the weekend! The result was that 3500 tons of assorted junk and mud were removed.

Through the 1970's, canal restoration became more organized, and, although WRG attempted to keep bureaucracy to a minimum, they later came under the wing of the Inland Waterways Association. The IWA, after discussions, would persuade local authorities to buy a derelict canal, supervise its reconstruction, and provide materials through the local canal society. WRG would assist with equipment and labor. If the canal was in private hands, there might be protracted discussions between the landowner and the local canal society or trust. Over the last 15 years, many successes have been notched up, with about 250 miles of canals restored, plus the skills acquired in rebuilding brick or stone lock chambers, building new wooden lock gates, sheep-piling the banksides, mass concreting, and constructing traditional style' accommodation bridges.

The second half of the illustrated lecture to the Middlesex Canal Association explained in some detail just how a canal, in this case the Basingstoke, was being restored. The Basingstoke Canal ran from the town of Basingstoke for some 30 miles and through 29 locks to the River Wey. The latter connects to the River Thames upstream of London. Legal restoration began in 1973 after the local canal society had campaigned since 1966 for the canal to be purchased by the two counties through which it ran. Hampshire moved first, obtaining the better part of the bargain: 15 miles and only one lock. Surrey followed three years later, paying (at today's rate) about $425,000 for their 15 miles and 28 locks.

The responsibility for overseeing the restoration lay with the Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society, who were the link between the small army of volunteers and the two counties. The counties provided the materials - sand, cement, bricks - and laid down the specifications, whilst the "new navvies" translated that into holes in the ground to be dug and then filled in, and all the other thousand-and-one tasks. As well as the local society, the London branch of WRG adopted the project as their "local" one, going there about six times a year. Other groups from farther north came down to give their support. London WRG was often given a lock, and it would be their task, say, to demolish all the facing brickwork. That would mean first digging a trench behind the top layer of coping stones, which sat on top of the brickwork, then rolling the stones back to expose the bricks. Scaffolding would be erected and someone would have to drive the dump truck down into the chamber so that all the rubble could be removed. The brickwork, some 28,000 individual bricks, was jackhammered off the lock walls. With one task in hand, many skills were learned. The canal bed was excavated and re-profiled using a backhoe excavator, but in Hampshire, where the canal was in water, possibly the only steam-operated dredger left in the country was slowly making its way along the canal.

As work progressed and the volunteer army moved down the canal, the gates, with good old English oak being used, were fitted to the locks, which just required minor landscaping. One hundred and eighteen wooden lock gates were built by volunteers in a disused army swimming pool. This had been a special project in itself, building new walls and a roof, and then supplying the place with electricity and water. Everything has been done to rebuild the canal so that it looks just as it was around about 1790 when it was built. Of course there are all the attendant "teething problems" that are bound to be associated with a project of this size. English canal buffs can now look forward to 1990, the waterway's bicentenary, and its rejoining to the canal system.

This is, one should bear in mind, just one of thirty canal restoration schemes taking place around Britain. There is the prospect of a 100-mile-long canal opening in the next five years and two 30-mile-long waterways, both crossing the Pennines, that should be returned to use in the next ten years or so. As it is mentioned in canal restoration history, during the 1950's and 1960's the "easy" canals were restored. During the 1970's and 1980's, the "hard" canals were rebuilt. Towards the end of this century we should see the so-called "impossible" canals restored. These include the Rochdale, only 30 miles long but with 94 locks to carry it over the Pennines from Manchester to Rochdale! There are already articles circulating about what the canal navvy will be restoring in the next century. Maybe those waterways that never got off the drawing board two hundred years ago!

SPRING WALK

Our spring walk was favored with beautiful weather. A convoy of a dozen cars followed the canal route through Winchester from the Medford line, with narration by Burt and Fran VerPlanck. Following the walk, we met in the beautifully renovated Winchester Town Hall, where Fran gave a slide presentation featuring our new copies of the antique glass slides.

CANAL MAPS REVISED

As part of our preparation for the American Canal Society bus tour of the Middlesex Canal, Dave Dettinger, Burt and Fran VerPlanck, David Fitch, and ACS's Bill Gerber scouted out the bus route the weekend before. Using copies of the town maps printed on the canal route markers, Burt prepared a detailed itinerary. He distributed copies to the ACS members on the tour, and these were so well received that we are planning to issue these maps in a set, together with Mary Clarke's narrative guide to the canal. Thanks to Burt for the hard work done (and, no doubt, more hard work to come).

GLASS SLIDES COPIED

For several years the directors have talked about getting copies made of our collection of antique glass slides. These black and white images were preserved between glass panes for showing with a 'magic lantern". Because it is hard to obtain a magic lantern to project them, the association has made very little use of these slides. They are also fragile, and a few have been cracked. The directors looked into copying them, but commercial studios quoted rather high prices. We contacted the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, whose photographic specialists had recommended an archive-oriented format to store the images as prints. SPNEA might be able to copy our slides, but there would be a long wait, and the result would be printed images, and not images we could use for programs or talks.

Fortunately for the association, the talents of our members are diverse, and Tom Raphael offered to see what he could do. Tom has copied the glass slides onto standard slide film, and these were shown at the spring meeting with a standard projector. Thanks, Tom!

OFFICERS & DIRECTORS 1989-90

| PRESIDENT | David A. Fitch |

| VICE PRESIDENT | David Dettinger |

| TREASURER / MEMBERSHIP | Howard B. Winkler |

| RECORDING SECRETARY | Burt Ver Planck 37 Calumet Road Winchester, MA 01890 |

| CORRESPONDING SECRETARY | Marion Potter |

| DIRECTORS | |

Betty M. Bigwood |

Wilbar M. Hoxie |

Edith Choate |

Jean M. Potter |

Jane B. Drury |

Thomas Raphael |

| Bettina Harrison 11 Hillside Avenue Winchester, MA 01890 |

Daniel Silverman 336 South Road Bedford, MA 01730 |

| Martha Hazen 15 Chilton Street Belmont, MA 02178 |

Frances B. VerPlanck 37 Calumet Road Winchester, MA 01890 |