Middlesex Canal Association P.O. Box 333 Billerica, Massachusetts 01821

www.middlesexcanal.org

| Volume 56 No. 3 |

April 2018 |

Please mark your calendars

MCA Sponsored Events

2018 Schedule

Spring Walk, 1:30pm, Sunday, April 22

Wilmington Town Park

Spring Meeting, 1:00pm, Sunday, May 6

A colloquy on Robert Thorson’s Book, The Boatman

16th Annual Bike Tour, 9:00am., Sunday, September 30

Fall Walk, 1:30 P.M., Sunday, October 14

Woburn Cinemas

Fall Meeting, 1 P.M., Sunday, October 28

TBA

The Visitor/Center Museum is open Saturday and Sunday, noon – 4pm, except on holidays.

The Board of Directors meets the 1st Wednesday of each month, 3:30-5:30pm, except July and August.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editors’ Letter

MCA Sponsored Events and Directions to Museum

President’s Message: “Progress on New Museum” – by J. Jeremiah Breen

Winter Meeting Recap – by Deb Fox

The Baldwin Seven-Dollar Bill – by Howard Winkler

Thoreau in Billerica – by Marlies Henderson

A Social History of the Middlesex Canal – by Alan Seaburg

Part Two of the Series – Interlude I: “The Canal 1803 and 1804”

A Social History of the Middlesex Canal – by Alan Seaburg

Part Three of the Series – Interlude II: “The Canal 1814”

Miscellany

Editors’ Letter

Dear Readers,

After three bad storms in a row, loss of power for days, and broken branches everywhere, there are finally signs of spring. Robins are back, plants are popping up, keep your fingers crossed!

Progress is being made in other areas as well. President J. Breen has provided us with an update on the new museum and the beginning travails of the Building Committee through the maze of town government in search of approval sign-offs. Diagrams and renderings are included.

The next two submissions are from Howard Winkler and Marlies Henderson. Mr. Winkler has some insight into that small paper item in the museum cabinet signed by Loammi Baldwin and Ms. Henderson takes us on a journey with Henry David Thoreau.

Our favorite section includes the next two parts of Alan Seaburg’s opus, A Social History of the Middlesex Canal. Interlude I: “The Canal 1803 and 1804” and Interlude II: “The Canal 1814” are included. We hope you find both thought provoking.

Our usual feature on upcoming events should keep you busy and check the miscellaneous section for information and the Web Site for updates. Enjoy the issue. Although the books are now closed on this issue, we begin the process of preparing for the next, Towpath Topics #57-1. Please consider submitting an item for consideration.

The Editors

MCA Sponsored Events and Directions to Museum

Spring Walk: The Spring Walk will take place on Sunday, April 22, 2018. Participants are encouraged to meet at 1:30pm at the Wilmington Town Park across from 760 Main Street (Rte. 38). The Appalachian Mountain Club and the MCA will host the 2-mile walk, roundtrip, along a section of the historic Middlesex Canal. Points of interest along the route will include the Ox Bow Turn where striations from the tow ropes are imbedded in the ledge along the canal, the signs of spring as the trek continues through the 14-acre tract gifted to the MCA by Stanley Weber and his daughter, Julia Ann Fielding, and finally Patches Pond. MCA member, Robert Winters will lead the walk accompanied by co-leader Marlies Henderson. Additional information is available at www.middlesexcanal.org.

Spring Meeting: The Spring Meeting (Annual Meeting) of the MCA is scheduled for Sunday, May 6, 2018 at 1:00pm in the Reardon Room of the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center located at 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862. A colloquy on Robert Thorson’s book The Boatman: Henry David Thoreau’s River Years is planned. Readers of the book will discuss the ideas presented in it. A short business meeting of the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal Association will precede the discussion.

John Williams’ New York Times Book Review: The Boatman,”about Thoreau’s relationship to the Concord River and alterations made to it during his lifetime, promises what publisher, Harvard University, calls, “the most complete account to date of this ‘flowage controversy.’”

16th Annual Bicycle Tour North: On Sunday, September 30, 2018 riders are encouraged to meet at 9:00am at the Middlesex Canal plaque, Sullivan Square MBTA Station (1 Cambridge Street, Charlestown, MA 02019). The ride will head north following the canal route for 38 miles to Lowell. There will be a stop for snacks at Kiwanis Park across from the Baldwin Mansion (2 Alfred Street, Woburn, MA 01801 ~12:30pm), stop for a visit at the Canal Museum (71 Falkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862 ~ 3:00pm) and arrive in Lowell in time for the 5:00pm train back to Boston. Riders can choose their own time to leave or join the tour by using the Lowell line which parallels the canal. The ride is easy for most cyclists. The route is pretty flat and the tour group will average 5 mph. Steady rain cancels; helmets are required. For changes and updates see www.middlesexcanal.org. The leaders of the tour are Bill Kuttner and Dick Bauer.

Fall Walk: The Fall Walk will take place on Sunday, October 14, 2018. Participants are encouraged to meet at 1:30pm at the southeast corner of the parking lot behind the Woburn Cinemas. The Appalachian Mountain Club and the MCA will host the three-mile walk along two level sections of the historic Middlesex Canal. MCA member, Robert Winters will lead the walk accompanied by co-leader Marlies Henderson.

Directions: From Rte. 128, take Exit 35, Rte. 38S. Proceed 1/10 of a mile and take a left turn off Rte. 38 onto Middlesex Canal Drive past the Crowne Plaza to the meeting place. Additional information is available at www.middlesexcanal.org.

Fall Meeting: The Fall Meeting of the MCA is scheduled for Sunday, October 28, 2018 at 1:00pm in the Reardon Room (possibly) of the Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center Located at 71 Faulkner Street, North Billerica, MA 01862. At the time of the publication a program and lecture are TBA.

Directions to Middlesex Canal Museum and Visitors’ Center

By Car: From Rte. 128/95

Take Route 3 toward Nashua, to Exit 28 “Treble Cove Road, North Billerica, Carlisle”. At the end of the ramp, turn left onto Treble Cove Road in the direction of North Billerica. At about ¾ mile, bear left at the fork. After another ¾ mile, at the traffic light, cross straight over Route 3A (Boston Road). Go about ¼ mile to a 3 way-fork; take the middle road (Talbot Avenue) which will put St Andrew’s Church on your left. Go ¼ mile to a stop sign and bear right onto Old Elm Street. Go about ¼ mile to the falls, where Old Elm Street becomes Faulkner Street; the Museum is on your left and you can park across the street on your right, just beyond the falls. Watch out crossing the street!

From I-495

Take Exit 37, North Billerica, south roughly 2 plus miles to the stop sign at Mt. Pleasant Street, turn right, then bear right at the Y, go 700’ and turn left into the parking lot. The Museum is across the street (Faulkner Street).

By Train:

The Lowell Commuter line runs between Lowell and Boston’s North Station. From the station side of the tracks at North Billerica, the Museum is a 3-minute walk down Station Street and Faulkner Street on the right side.

President’s Message, “Progress on New Museum”

by J. Breen

“I’m not fixing the roof! How would you like the building?”, Bill Donovan, president of Pace Industries’ Cambridge Division in the Talbot Mills, exclaimed after written notice from the Billerica Historic Districts Commission of the need for repairs.1

On May 5, 2012, the directors of the Middlesex Canal voted to accept the gift of 2 Old Elm Street. The first cost of this gift was paying lawyer Dave Fitch for 4½ hours to review the purchase and sale agreement. Dave was president of the association in 1987- 1990 and first chairman of the Historic Districts Commission in 1990. The cost of the gift so far has been more than $26,000, mostly for architectural fees. That cost does not include the work of the building committee, J, lead director Betty Bigwood, the artist Dahill, and the late Tom Raphael. Nor the efforts of Bill Gerber, Bob LeBlanc, et al.

A milestone this past March was the Middlesex Canal’s first application to the government for permission to renovate 2 Old Elm St for adaptive reuse as a visitor center/museum. Permission would be needed from the Conservation Commission, Zoning Board of Appeals, Board of Health, etc. The building committee chose to apply for permission first from the Historic Districts Commission. Presumably a majority of the commission would vote for adaptation of the 150-year-old warehouse as planned by the Middlesex Canal Association rather than let the crumbling building be demolished by nature. The substantive basis for permission was the following before and after JPEGs:

Before

After renovation for use as a visitor center/museum

The report of the architect after meeting with the commission on March 14, 2018, is below. Permission from the commission to renovate 2 Old Elm is required by town law as the building is in the Billerica Mills Historic District.

The commissioners favored the attempt at the major project of renovating a dilapidated, 150-year-old warehouse by the volunteers of the Middlesex Canal Association. Changes were recommended with only one commissioner having a “must” of muntins on the exterior.2 The ballpark estimate for slate-colored architectural shingles of asphalt and fiberglass is $9,000. Metal is $27,000. A majority vote in favor of the project with the modern adaptations for reuse of the 150-year-old warehouse as a visitor center/museum is likely.

The next commission from which permission will be requested is Conservation.

Previously one or more commissioners have considered requiring that work be done from a barge. Since that meeting, a demolition sub-contractor has said he can remove the collapsed roof by working inside the building with scaffolding on the exterior for brick repair. The building committee for Old Elm Street still thinks reuse of the building is worthwhile, notwithstanding possible costly requirements, e.g., a slate-like roof and working from a barge, and necessary given the recent $1200 increase in annual rent for 71 Faulkner Street with more increases to come.

Report of the architect, John Caveney, after March 14, 2018 meeting with the Historic Districts Commission.

Hi Betty and J,

We were the only item on the agenda at the meeting this evening, and it went very well. We received approval of concept and approval to re-purpose the building to its new use subject to submission of final drawings and material selections. They will be interested in all materials selected, including but not limited to, roofing, windows, railings, decking, shutters, columns, etc. Below are my bullet point comments:

- Roofing: Do you all know if the building’s original material was slate? If so, they would like a material that mimics slate in color and appearance. One member mentioned that if the original material was cedar shakes, then Certainteed Presidential has an asphalt shingle line that matches cedar shakes. Another board member stated metal could be nice. I believe we have some leeway with material choice here.

- Shutters: Solid wood (no slats). They like the dark green.

- Windows: 6 over 6 are fine as long as we mimic the original windows. Muttons must be on the exterior versus in-between the glass panes.

- Exterior Doors: Solid wood door at both entrances

- Decks and Rails: details and materials to match throughout

- South Entrance: No glass is preferred (meaning they would like energy code required vestibule on the inside of building). For the entrance roof, they recommended possibly incorporating gable end details.

- West Entrance: If we go with a covered entrance here, they would like it to match the character of the South entrance.

- Industrial Feel: multiple members thought it would be nice to incorporate industrial elements (@ entryways and @ railing details). They recommended looking at details from surrounding mill buildings.

Overall a very good meeting. Let’s plan to discuss soon and we can start to incorporate into our drawings.

2 Exterior muntins are one of the most important features of an historic building in maintaining its architectural integrity. Comment in a March 17 email from Deb Fox, a Middlesex Canal Association director. Deb has a master’s degree in preservation and was part of the establishment of the Historic Districts Commission with lawyer Fitch.

Winter Meeting Recap

by Deb Fox

The Winter Meeting of the Middlesex Canal Association was blown to order again by President J. Breen on February 11, 2018 at 1:00pm in the Reardon Room of the Faulkner Mill in North Billerica. He reminded members that the Annual Meeting would be held on May 6, 2018, to vote on new Proprietors.

President Breen then introduced the guest speaker, long-time association member, Fred Lawson. Mr. Lawson narrated his beginnings with the Association dating to 1961, at a meeting he attended at the Billerica Historical Society, through his interesting and varied life, including his reenactment of Colonel Baldwin and his foray into traditional basket-making.

Fred Lawson, February 11, 2018

Questions from the audience changed topics frequently, with audience members responding to each other as well, creating interesting discussions. Helen Potter wanted members to know how her husband rescued the Talbot Mill glass negatives from the trash at the urging of his mother, Marion Potter. Prints now hang in the Reardon Room.

There were approximately 20 to 25 attendees who filled the room. When the lecture was completed and every question answered, Betty Bigwood’s ham biscuits made their much-anticipated appearance and everyone left the building fully satisfied.

Winter Meeting , February 11, 2018

The Baldwin Seven-Dollar Bill

by Howard Winkler

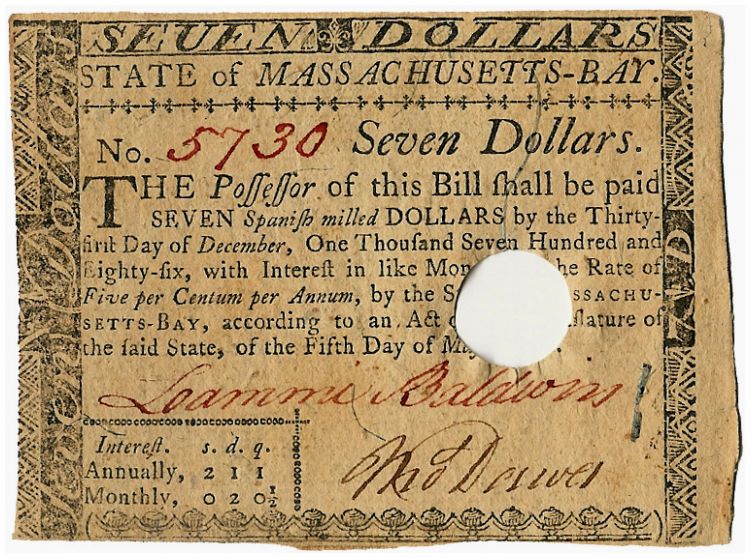

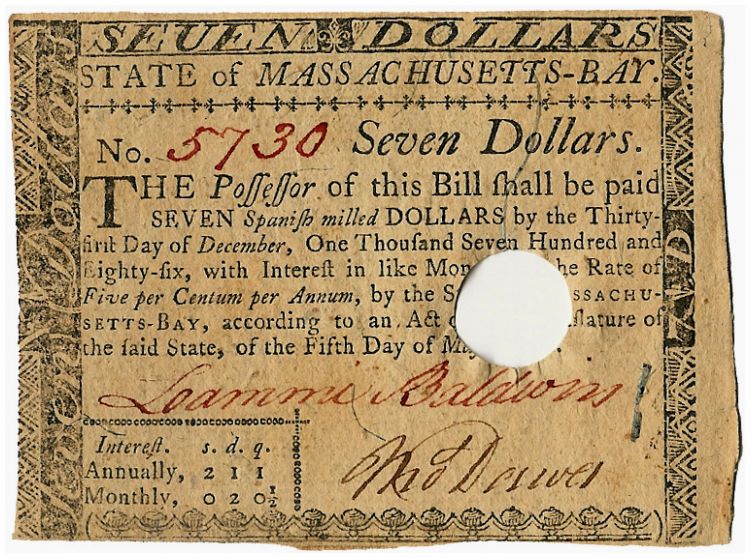

In the April 2017 issue of Towpath Topics, I wrote an article that included the inscriptions on the pedestal of the statue of Loammi Baldwin, located on Route 38 near its intersection with Route 128. The particular words A MEMBER OF THE COMMITTEE TO SIGN THE PAPER MONEY OF MASSACHUSETTS COLONY caught my attention.

An Internet search brought forth a seven-dollar bill issued by the State of Massachusetts-Bay and signed by Baldwin.

The words on the bill follow:

SEVEN DOLLARS

State of Massachusetts-Bay.

No. 5730 Seven Dollars.

The Possessor of this BILL shall be paid

SEVEN Spanish milled DOLLARS by the Thirty-

first Day of December, One Thousand Seven Hundred and

Eighty-six, with Interest in like Money, at the Rate

of Five per Centum per Annum, by the State of MASSACHU-

SETTS-BAY, according to an Act of the Legislature of

said State, of the Fifth Day of May 1780.

Interest, s. d. q.

Annually, 2 1 1

Monthly, 0 2 0½ |

It was nice to find an example of Baldwin’s handwriting. He had good penmanship, but this is not surprising in the age in which he lived.

I found an Internet site that indicated a Spanish milled dollar was worth six shillings (s.). Five percent of seven Spanish dollars is 2.1s. There are 12 pence (d.) in a shilling, so 0.1s. equals 1.2d. There are four farthings (q.) in a pence, so 0.2 d. equals 0.8q. Five percent of seven Spanish dollars equals 2s.1d.1q. rounded up as indicated on the bill so the per annum percentage and interest paid annually, agree, and not surprising. (This was check on my understanding.)

At the beginning of the War of Independence, the Continental Congress authorized the issuance of paper money, Continentals. War cost money to outfit, feed, and arm an army. Continentals proved to be a poor economic instrument as they were backed by nothing more than the promise of “future tax revenues” and prone to rampant inflation, and ultimately had little fiscal value.

Bills were issued by Massachusetts in denominations of $1, $2, $3, $4, $5, $7, $8, and $20 bills, and represented shares of commodities such as corn, grain, cattle, and, ultimately, silver. When they were redeemed, a hole was punched in the bill or it was stamped “Interest paid one year.” There are two signatures on the front and a guaranty signature on the back of the bill. Signers were selected from among the outstanding men of Massachusetts and were paid a small fee for their service.

Editors’ Note: US Inflation Rate, 1786-2018 ($7): According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, the dollar experienced an average inflation rate of 1.4% per year. Prices in 2018 are 2434.9% higher than prices in 1786. In other words, $7.00 in 1786 is equivalent in purchasing power to $177.44 in 2018, a difference of $170.44 over 232 years.

Inflation Calculator, Alioth Finance, http://www.in2013dollars.com

Thoreau in Billerica

by Marlies Henderson

If all claims for oaks where George Washington rested were true, this founding father would have slept through his presidency without ever waking up. Similarly, James J. Kilroy (1902-1962) would be an omnipresent graffiti artist long after he died. But in 1839 Henry David Thoreau really was in Billerica, with an overnight along the Concord River. He slept on Billerica soil! The value of this fact is not to be swept under the rug. Let’s memorialize where the pop star roamed, and harvest the fruits of his fame. Billerica can ride this wave, particularly on its Concord River and multiple remnants of the Middlesex Canal - Thoreau’s highways, as journaled in his book “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers”.

First published in 1849, the book seems to be the travel log of a boat trip from Concord, MA to Hookset, NH and back. Thoreau took the trip with his brother John. After John had died from tetanus in 1842, Thoreau sought seclusion at Walden Pond with the aim to write about that excursion, ten years after, and process the grief of having lost his late brother. The actual trip took two weeks, but artistic license permitted Thoreau to fill hundreds of pages describing one week; seven daily chapters. The book didn’t sell at the time. Thoreau quipped in a journal that his library consisted of 900 volumes, 700 of which he wrote himself; all unsold copies of “A Week” returned to him by the publisher. Two and a half centuries and many editions later the title has grown popular, and I bought and browsed it.

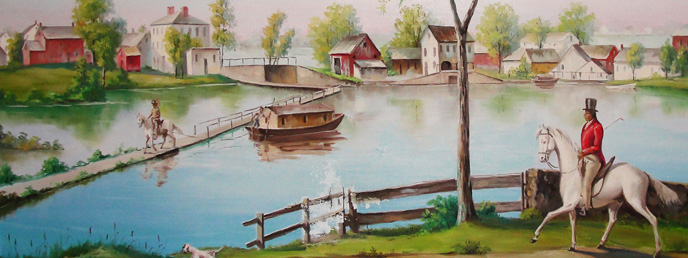

Musketaquid. Replica of Thoreau’s Boat most well known boat; the dory the Thoreau brothers

built in the spring and used as their mode of travel in August and September.

Boat loan courtesy of Concord Museum.

Photo taken by Juliet Wheeler on the shore of Fairhaven Bay, September, 2016.

Mourning his brother between the lines, Thoreau mulls religion, love and friendship, but also fishing, poets, and heroes of mythology. He puts forward countless digressions, spending a fraction of his writing on the subject matter of my quest: The trip itself: they set out, relatively late on Saturday, from the Sudbury River where the dory they had built a few months before was moored. Loaded with melons and potatoes, they rowed until sunset, about 7 miles to Billerica where they camped “on the west side of a little rising ground which in the spring forms an island in the river.”

Continuing the next morning, Thoreau notes they “passed various islands”. “The one on which we had camped we called “Fox Island””, and an island overrun with grapevines is baptized Grape Island. In other work, Thoreau uses ‘Grape’ and ‘Jug’ interchangeably to describe the rocky island in deep water, located one mile downstream from Fox Island.

When I planned to visit the Concord Free Public Library last winter to research Thoreau’s boat trip on the Middlesex Canal for a Wayside Exhibit on Lowell Street, the Billerica Historian urged me to also study Thoreau’s manuscripts relative to this first campsite in Billerica in 1839.

Running a Winter Walks program in Billerica, I sometimes, due to storms, have to make multiple pre-treks to ensure a seamless event. One trail tangent in Carlisle Greenough Land drew me out each time to a captivating spot in the floodplain. The view arrested me. Ultimately, at that same attractive area, when I had thirty followers in tow, I pointed across the Concord River. The voice booster amplified my words: “if we’d go from here, straight as the crow flies, we’d find Great Meadows Wildlife Refuge, but we can’t see it, because there is sort of a dividing ridge, a little rising ground …”, and that’s when a sprite sprung it upon me: Thoreau was there!

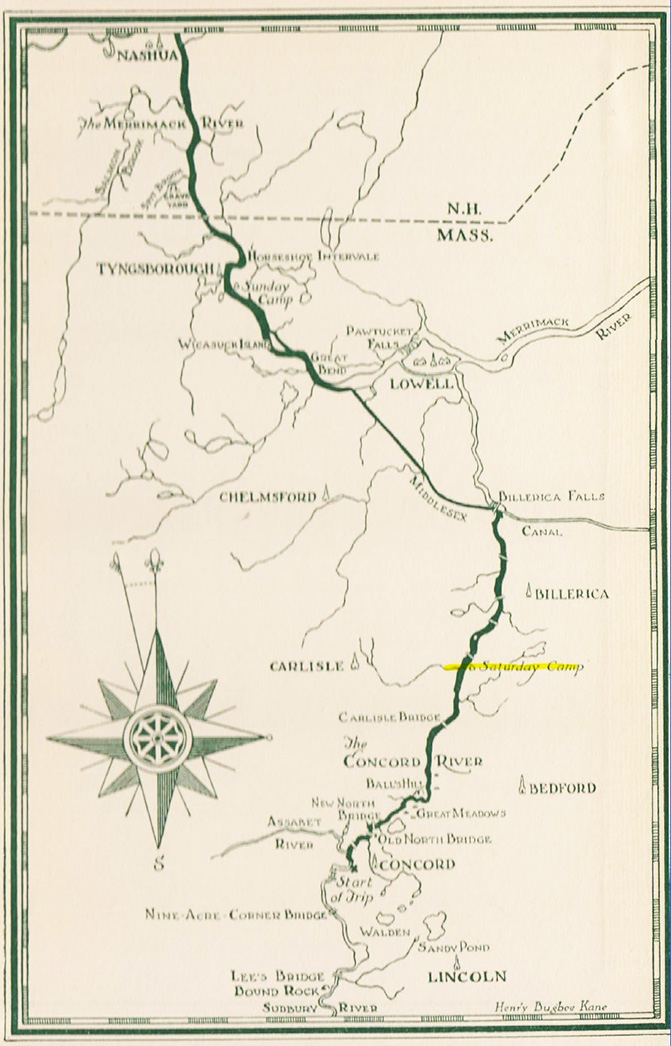

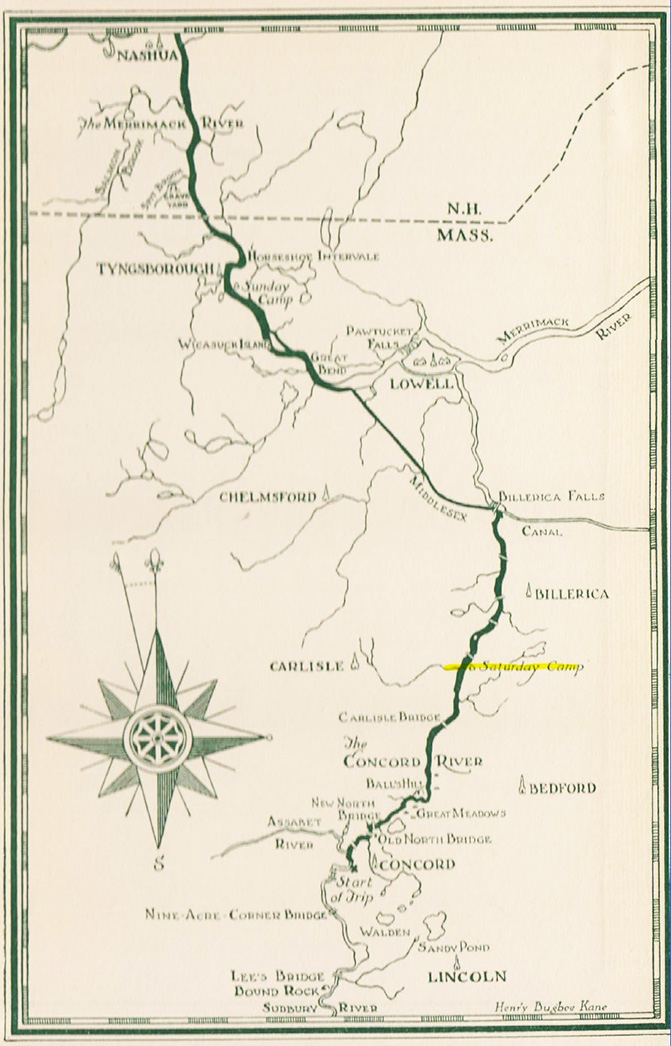

Based on this epiphany as well as on abundant topographical and literary evidence, the location of Thoreau’s first campsite is obvious. Frequent paddles, hikes and waders complement desk research. With all due respect for federal institutions and Thoreau aficionados, they have so far either wisely avoided conclusive statements, or assumed misguided guesses. A Jug Island photograph from the Herbert Wendell Gleason collection is mistakenly matched with the Saturday on page 38 of a 1906 edition of “A Week”. Illustrator Henry Bugbee Kane gets it right with a detailed map on the endpaper of a 1954 edition.

The famed recreational reputation of Billerica during turn of the 20th century clouds the memory of Thoreau passing through Billerica; the “Bretton Woods of Massachusetts”. In 1906 Gleason visited the Riverhurst Boathouse, and John Stearns (born 1845) sold “The Island”, the parcel where Thoreau once camped, to a mill worker of Lowell. Typical of the river oriented recreational activities enjoyed at that time by visitors to Billerica and Bedford, the riverfront neighborhood was rebranded ‘Greenwood Grove’. In 1930 the Greenwood family paid taxes for 17 cottages. Soon after, the cottage business slumped.

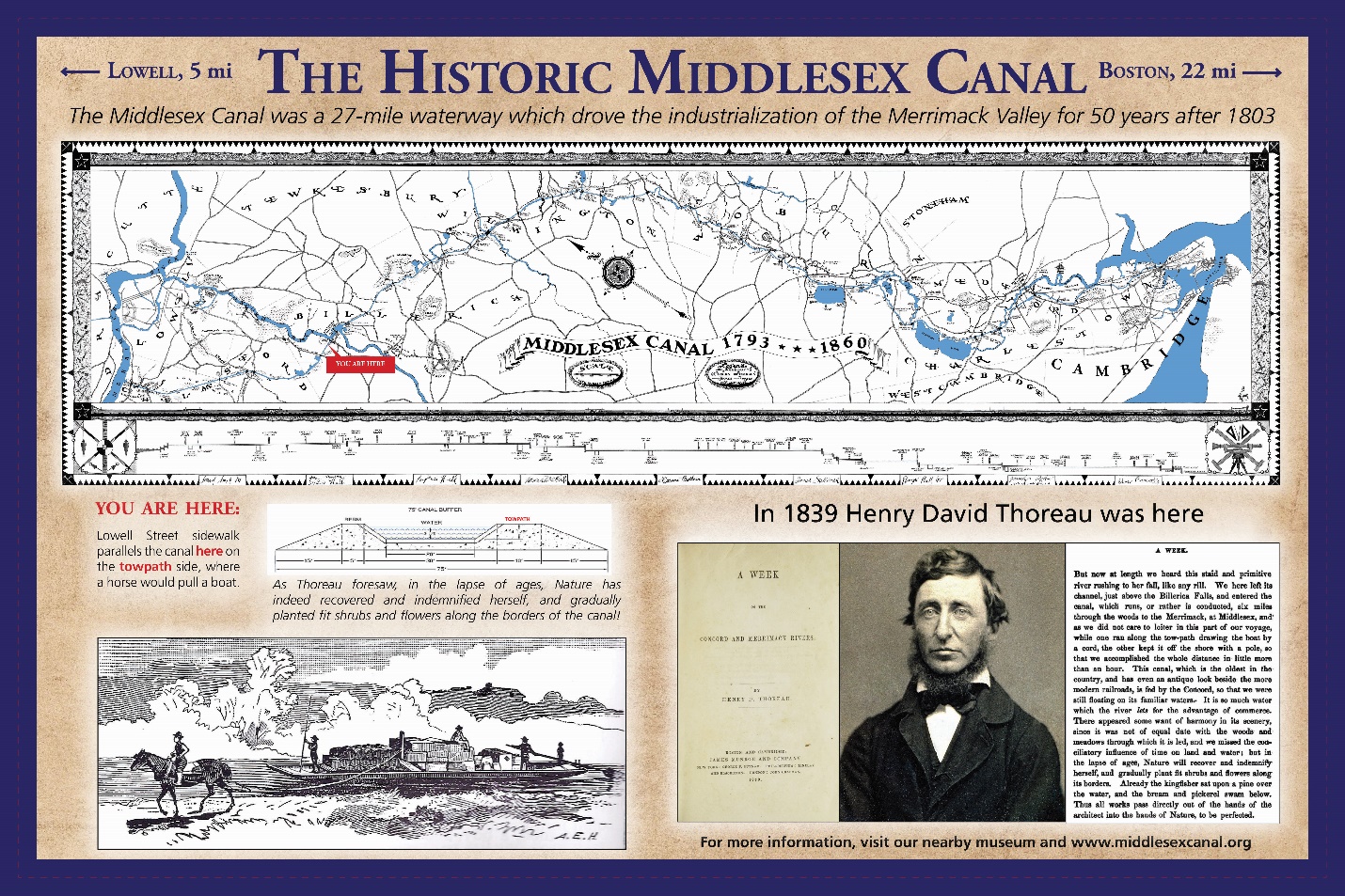

Not only did Thoreau sleep in Billerica, he also navigated locks into the Middlesex Canal on Sunday, just above the Talbot dam, or rather the ‘Billerica Falls’ as he names them. The Boston & Lowell Railroad had opened four years earlier, and business for the canal ebbed away. Not impressed with engineering feats, the brothers “did not care to loiter in this part of our voyage, while one ran along the tow-path drawing the boat by a cord, the other kept it off the shore with a pole, […].”

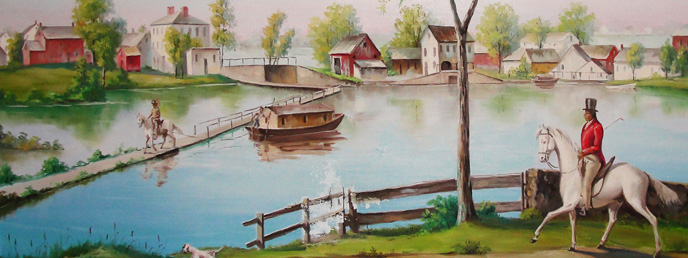

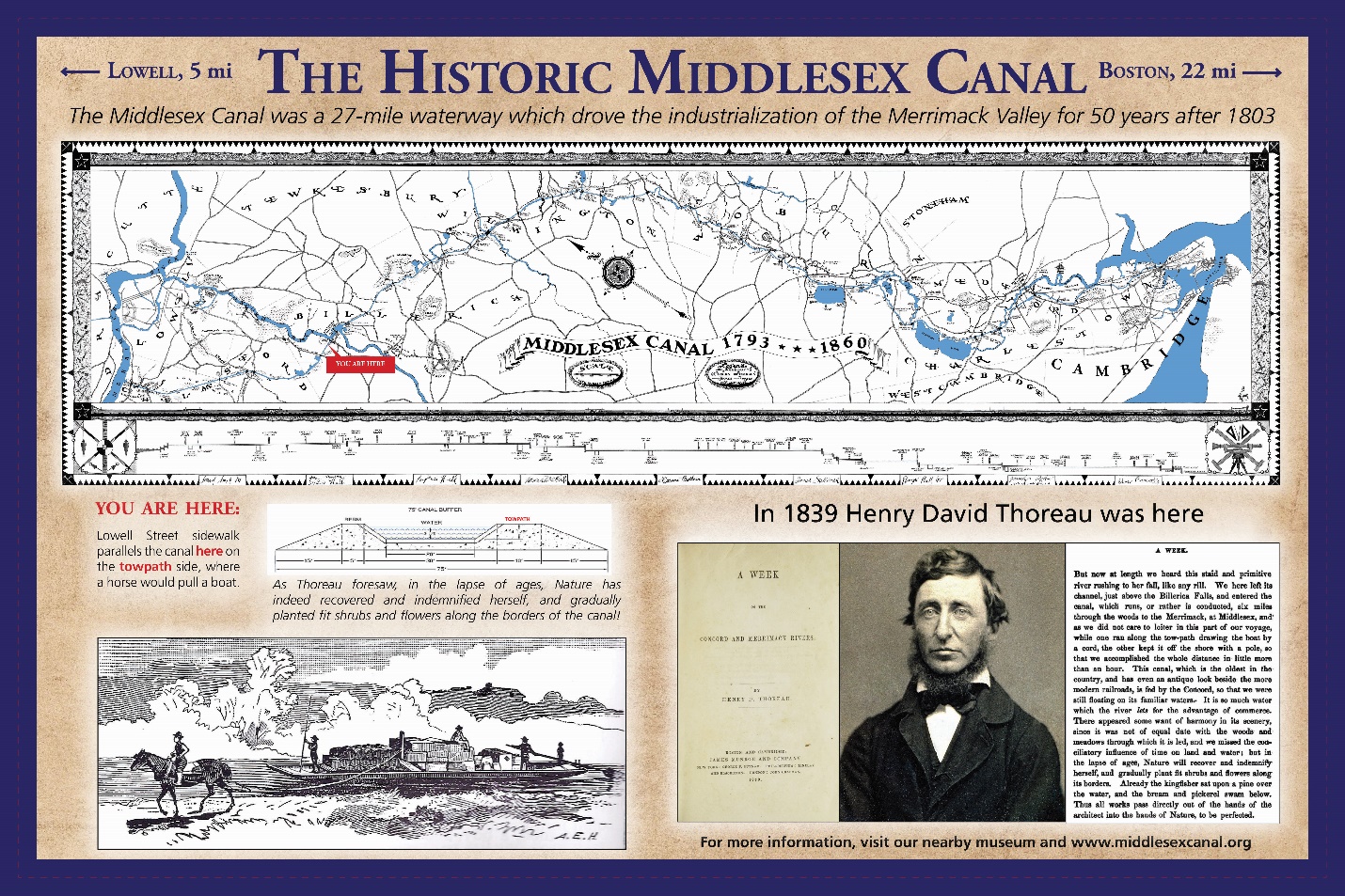

36” x 24” wayside exhibit on Lowell Street, North Billerica, to be installed May, 2018

“This canal, which is the oldest in the country, and has even an antique look beside the more modern railroads, is fed by the Concord, so that we were still floating on its familiar waters. It is so much water which the river lets for the advantage of commerce. There appeared some want of harmony in its scenery, since it was not of equal date with the woods and meadows through which it is led, and we missed the conciliatory influence of time on land and water; but in the lapse of ages, Nature will recover and indemnify herself, and gradually plant fit shrubs and flowers along its borders.” And she did.

Reportedly sailing fifty miles on Friday, the last day of the book, thanks to a true or imagined strong northerly tailwind, there was no need for the brothers to camp in Billerica during the rapid passage back to Concord. Unrealistic perhaps, but “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers” has so much more meat than a travel log. I merely researched it for the bare bones of the trip – and only for Billerica – to memorialize Thoreau’s presence with a wayside exhibit which helps sidewalk users imagine him there, either in the dory or running on the towpath, pulling it by a cord. Not a ditch, but a technological marvel whose half-million-dollar cost in 1803 prompted the secretary of the Treasury to call it “the greatest work of its kind that has been completed in the United States.”

1954 Map by Henry Dugbee Kane

Literature:

Thoreau, Henry David. The Writings of Henry David Thoreau. a Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Houghton Mifflin & Comp., 1906.

The Concord and the Merrimack: Excerpts from A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Arranged with notes by Dudley C. Lunt; Illustrated by Henry Bugbee Kane. College & University Press, 1965.

“Deep Travel: in Thoreau’s Wake on the Concord and Merrimack.” Deep Travel: in Thoreau’s Wake on the Concord and Merrimack, by David K. Leff, University of Iowa Press, 2009. “Thoreau Gazetteer.”

Thoreau Gazetteer, by Robert F. Stowell, Princeton University Pres, 2016.

http://www.mappingthoreaucountry.org/maps/map-1/

“Wild Fruits: Thoreau’s Rediscovered Last Manuscript.” Wild Fruits: Thoreau’s Rediscovered Last Manuscript, by Henry David Thoreau et al., W.W. Norton, 2001, p. 154.

The following interlude is reprinted from Alan Seaburg’s e-publication A Social History of the Middlesex Canal.

INTERLUDE ONE: THE CANAL 1803 AND 1804

It is said, that the Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal will shortly realize the fruits of their enterprise and perseverance. Immense numbers of rafts, composed of large logs, as well as of such, as are designed for masts and spars, are ready to be floated into Charles’ River. We are credible informed that the quantity of timber, for this purpose, which is already swimming in the Merrimack, or on the banks of that river, amounts to at least four millions of tons. The price of timber is consequently greatly enhanced of late throughout the neighborhood of the canal.

The Boston Weekly Magazine, April 23, 1803

The Middlesex Canal, from Merrimack River, to Boston, is completed, and will be in operation as soon as the ice is dissolved. This is the greatest public enterprise that ever was accomplished in the New-England States – and we hope the Proprietors will soon be remunerated for the very heavy expenses they have incurred in finishing this important Canal.

The Boston Weekly Magazine, March 24, 1804

THE PORT OF BOSTON AND THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

The Middlesex Canal began its full transportation operations of commercial goods and travelers between Boston and the Merrimack River at today’s Lowell in 1803. Planning for it and the development of its business model, plus acquiring the needed land for its route, hiring laborers, digging the roughly 27 mile canal bed, constructing towpaths, bridges, locks, aqueducts, barges, and the necessary buildings for running the enterprise, as well as a thousand and one other details, had started ten years earlier. The aim of those who conceived and built the Canal was to further enliven and enrich the trade and flow of goods between the Port of Boston, the State’s Merrimac Valley region, and as much of New Hampshire as it could. For those unfamiliar with this old Canal, its successes and ultimate financial failure for those who had invested in the project, its story has been well related in several books which are easily available in libraries, bookstores including that of the Middlesex Canal Museum, and online.

This study, therefore, will not attempt another detailed account about the Canal but instead will focus on what some Canal enthusiasts, maritime scholars, and historians of the New England Region have general concluded were its chief contributions in making Boston New England’s leading urban seaport. These views are easily summarized.

The respected Harvard historian, the late Samuel Eliot Morison, in his volume The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783-1860, wrote that “The Middlesex Canal, by tapping the Merrimack River at Chelmsford, diverted from Newburyport, the lumber and produce of southern New Hampshire.” (1)

Many have supported this claim. For example, Michael J. Connolly in Capitalism, Politics, and Railroads in Jacksonian New England stated, “The Merrimack valley developed at an even faster rate, as the towns along the wide river grew to become the northern link in the nation’s industrial revolution. Like the seacoast, this region benefited from an extensive road and turnpike network stretching north-south along the river bank and east-west reaching toward Keene and the Connecticut River. In addition, river improvement like locks and canals made the Merrimack a viable and profitable transportation alternative, especially after the Middlesex Canal opened up a clear avenue to Boston in 1805.” The goods so transported he added included “large amounts of timber” that were used “in house construction and ship-building . . . . [that] were conveyed to Charlestown by means of the river and Middlesex Canal.” (2)

Diana Muir drew the same conclusion in her book Reflections in Bullough’s Pond Economy and Ecosystem in New England writing that “The Middlesex Canal—twenty locks and twenty-eight miles linking New Hampshire’s Merrimack Valley with Boston harbor—spelled the end of commercial prosperity for the Merrimack’s natural outlet at Newburyport when it opened in 1803, which was exactly what the Boston proprietors had in mind.” (3)

In addition to limiting business competition from Newburyport merchants, the Canal is further understood and proclaimed to have been the chief reason why Boston became the most important of all the mercantile centers in New England.

The New England Historical Society put this quite plainly, declaring on its website that the Canal’s creation “cemented Boston’s position as the commercial hub of New England.” (4) And Mary Stetson Clarke in her study of The Old Middlesex Canal agreed pointing out that urban Boston “had no large river of any consequence flowing into its harbor and bringing to it the riches of the newly opened lands” of the Merrimack valley and southern New Hampshire. As a result the Port of Boston, once New England’s “acknowledged leader in commerce” had seen its trade suffer serious decline. It was only “new markets” that could “revitalize the economic life of Boston and return her to leadership” which was what the Middlesex Canal allowed. (5)

Finally, in support of this claim, both the Middlesex Canal Association and the state of Massachusetts established Middlesex Canal Commission have declared at various times, and in a recent publication, that it was the Canal which was “largely responsible for the growth of Boston as a world city.”

Our task now is to try and understand the validity of these claims concerning the true impact and relationship between the Middlesex Canal and the city and Port of Boston.

To do so properly we need to start with the founding of Boston in 1630, and see how the town, after 1822 the city, developed into its nineteenth century status as New England’s leading urban seaport.

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

It was in this century that several European nations of the Atlantic World seriously commenced to re-people the eastern seaboard of the North American continent, especially for the focus of this essay in what came to be called New England. If at first it started with voyagers of discovery and small efforts involved with fishing and fur trading, it quickly evolved in the early seventeenth century into a period of active colonization.

From 1630 onward the earliest Boston merchants, as those in the other settlements along the coast did, based an important part of their economy for the colony on acquiring, usually from the original population of the area, the Native Americans, beaver pelts and other furs, and then selling them at a profit back in England. With the cash earned there they were able to purchase, and resell to their Greater Boston customers, the every day goods that they desperately needed and could not produce. These included among other items iron pots, pans, weapons, cloth bolts, stockings, blankets, farming tools, and building materials.

This approach worked until the availability of pelts diminished which forced the “white” hunters and “friendly” native hunters to extend their animal search farther and farther up the various inland river ways. The competition in this trade included Boston, Plymouth, Salem, New Haven in Connecticut, plus some of the new communities that had been established in New Hampshire and Maine.

Eventually the supply was reduced so much that the colonists shifted their chief economic focus from fur back to fishing, which had also been a significant part of their commercial activity. It now became, however, as Bernard Baiyln indicated in his study on seventeenth century New England merchants a “cornerstone of the region’s economy.” (6) In addition to fishing the trade soon came to focus on agricultural produce followed next by lumbering, which included not merely shipping masts, boards for constructing houses and other buildings, but such items as barrel staves, hoops, and pipe staves.

Then, starting in 1664, the purchase of West African slaves by Boston merchants and families was added to this mix. For examples, in Medford Major Jonathan Wade had five slaves that he valued at 97 pounds and a Mr. Collins of that town was happy to let his neighbors see his personal slave Elline publically whipped.

From his extensive research on Boston merchants and their trading Bernard Baiyln was able to arrive at this conclusion: “As trade rose and the European shipmasters sought a familiar New England harbor, where reliable merchants would be waiting to provide ship stores and cargoes, Boston, with its excellent harbor, access to the Massachusetts government, and flourishing agricultural markets, became the major terminus of traffic originating in Europe. To it were drawn the produce not only of the surrounding towns but also of New Hampshire, Rhode island, and Connecticut as well. With the exception of Salem and Charlestown, the other promising mercantile centers slipped back toward ruralism.”(7)

In other words, Boston’s ships by the arrival of the early decades of the nineteenth century had visited “every port of the Western world,” and by doing that they had “established a tradition of skillful trading which was the basis of Boston’s maritime success for 200 years.” (8) The origin of this later success clearly went back to the decades of the seventeenth century; for even then, as our brief examination of Boston trade has shown, its port was “the main seat of New England commerce.” (9) And except for during the Revolutionary War it never lost that commercial prominence, although it always had healthy competition from other communities like for example, Salem, Massachusetts.

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

During this new century Boston steadily continued its development to become in tine New England’s most significant early nineteenth century commercial port. However the start of the troubles between the colonies and their mother country temporarily halted that process. The final straw for the colonists in their ongoing disagreement with “Mom” came when Parliament passed in 1774 the Boston Port Act. That Act, the result of the famous Boston Tea Party, closed the port completely to shipping until the town made economic restitution for the tea that had been dumped into the harbor. That Boston refused to do and so, as Jacqueline Barbara Carr declared in After the Siege A Social History of Boston 1775-1800, the result was the “commercial death knell for the community,” and “the consequences soon manifested themselves during the months that followed. By year’s end events would turn the city [town] into a shadow of its former self.” (10)

The battles in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, between the British Regulars and the “soldiers” from those towns and other local neighborhoods, which had been brought on by the occupation of Boston by the British, led to the siege of the town by Washington’s newly formed Continental Army. This was to last until March 17, 1776 when the British suddenly finding cannons looking down upon them from Dorchester Heights folded their tents and sailed away.

During those months the town’s population had declined from 15,000 inhabitants to less than 3,000, and its busy port had just about ceased to exist. The result was a “war-torn community weakened economically, physically, politically, and socially. “ (11) Nevertheless, its people, those who had remained in the town during that fateful year, plus those who had fled for safety reasons, along with new folks from other places who came because they saw it as an opportunity to better their chance in life, soon set out to rebuild the community.

So Bostonians began the job of restoring their trading town. First they revived the structure of their government so that it properly, and fairly, tried to care for all the genuine public needs of its citizens, especially those connected to policing, education, and health. But just as important they reminded their representatives to the General Court “to cherish and extend our Trade.” Fortunately some merchants had come out of the war in a fairly good financial condition due to their involvement in privateering. That, along with the fact that the Navigation Acts which had closed the port no longer existed, meant that trade could begin again with European countries, especially with Russia, Sweden, Spain, and France. Soon “Boston harbor filled with foreign ships, and wharves ‘heaped high with foreign goods.’” (12) Traders were even starting to send ships to China, which flourished once the merchants found their market there in the 1790s, which was shipping Northwest Pacific furs to China. “The ensuing China trade and the new national government’s tariff legislation,” Carr declared, “signaled a bright future for maritime Boston.”(13)

It took roughly two decades to achieve that, but working cooperatively together Boston became again “New England’s most important and vital urban center.” (14) Carr in her study of Boston felt that it was the Revolution that “was the catalyst that set this process in motion, altering both individual lives and community institutions.” (15) These years now saw the Port of Boston shipping such items as fish, rum, whale, cod oil, furs, boards, staves, candles, leather, shoes, tea, coffee, molasses throughout the Atlantic world, and eventually beyond. This brought prosperity to shipyards and their owners as well as to the artisans and laborers employed there. The town’s eighty or so wharves had in 1795, for example, welcomed nearly eight hundred commercial vessels carrying cargoes bound for local and distant merchants and traders.

Indeed, “By the year 1800, the Port of Boston had reached unprecedented prosperity. It had passed Philadelphia in both coasting and foreign trades, and Boston’s total tonnage was second only to that of New York.” (15) Clearly it is fair to conclude then that Boston had regained its earlier position as New England’s leading port.

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

As the new century opened Boston and its port, its merchants and its capitalist adventurers, or as we often prefer to term them entrepreneurs, were in full trading mode. While there were several reasons for this success the most significant was the fact, as Samuel Eliot Morison put it bluntly in his Maritime History of Massachusetts, that “by 1792 the trade route Boston-Northwest Coast-Canton-Boston was fairly established.” (16) As a result the future of commercial Boston appeared bright and promising, not simply for the business community, but for those who made trading concerns possible. Morison identified them as the community’s middle class citizens. “The backbone of maritime Massachusetts, however,” he wrote, “was its middle class; the captains and mates of vessels, the master builders and shipwrights, the rope makers, sail makers, and skilled mechanics of many different trades, without whom the merchants were nothing.” (17)

Assisting the development of the growing trade was the continued increase in the town, after 1822 the city, of its population base. By 1800 that had reached 25,000, which was roughly 10,000 more than it had been in 1775. The first three decades of the century saw even more people moving in although it was not until the 1840s that Boston experienced its dramatic increase in population, which went from around 93,000 to 136,000. That, of course, was due chiefly to the potato famine then occurring in Ireland that drove thousands to Boston and other cities in America.

If the future for the Port of Boston seemed rosy at this point, there soon came several significant events, which changed the dynamics of the situation. The first was the rise to power in France of Napoleon Bonaparte. From 1799 though to 1815, and his defeat by the British at Waterloo, he was effectively the man who ruled France. As such during this period he conquered a large part of Europe. His actions eventually disrupted trade and commerce between Europe and the North American edge of the Atlantic basin.

The situation only got worse with the election of Thomas Jefferson as president in 1800. Federalist Boston did not like the new president. First he favored France rather than England, as they did, and further he was not a friend to maritime commerce as previous presidents had been. Then in 1802 Napoleon made peace with England. This resulted in a series of “Orders” and “Imperial Decrees” which tried to eliminate “neutral shipping” from the ports of both countries. That was indeed bad news for American shipping. Finally Jefferson acting to defend the rights of neutrals issued in 1806 The Embargo Act, which “forbade any American vessel to clear from an America harbor for a foreign port, and placed coasting and fishing vessels under heavy bonds not to land their cargoes outside the United States.” (18) It was to remain in effect through early 1809, and was followed three years later with James Madison’s 1812-15 War with England.

Massachusetts opposed both the Embargo and the War, and both proved to be disasters for its economy, especially for the commerce of Boston. For example, in 1813 only “five American and thirty-nine neutral vessels cleared from Boston for foreign ports.” (19)

Yet Boston was a resilient city, and so by the 1840s its commercial trade was even more significant than before the start of the kerfuffle that opened the century. “In shipping and foreign commerce,” Morison declared, “she managed to remain a good second to New York, despite the geographical advantages of Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans.” (20) Indeed, the decade 1845-1855 proved to be the city’s most prosperous maritime period. Yet in the long run it could not keep pace with the Port of New York and its Hudson and Erie Rivers. Nor in the end with the challenges that were made after the Civil War to Boston and New England’s maritime economy by the rise of “industry” and “manufacturing.”

Peter Temin in his introduction to Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England wrote this overview about Boston and its special region. “The economic history of New England,” he said, “is as dramatic as the transformation of any region on earth. Starting from an unpromising situation of losing population in the eighteenth century, New England came to lead the United States in its progress from an agricultural to an industrial nation. Then, when the rest of the country caught up to this region in the middle of the twentieth century, New England reinvented itself as a leader in the complex economic scene we call the ‘information economy.’” (21)

THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

To best understand the actual contribution of the Middlesex Canal to Boston and its port, as well as to the city’s place within the story of the New England Region, one needs to start first with a simple summary declaration of just what that was: and that is that the Canal was but one of several enablers that helped to make nineteenth century Boston a first class American city – or to use the popular, and so much more impressive term of today –a World City.

Analyzing this conclusion can begin with the statement that Admiral Morison, and all who agreed with him, which means everyone writing about the Canal, were steady on course about Newburyport. For Sullivan and Baldwin’s Canal did just what they and their merchant financial backers wanted it to do. Which was to funnel the majority of the Merrimack’s trading resources directly to the Port of Boston. As Harry C. Dinmore observed, “These men were interested in developing Boston as the trading center of the back country” and “they correctly foresaw the great advantages of landing material directly in Boston.” (22)

Now let us examine the other major claims for the Canal, which were listed at the start of this essay. They include the following: “cemented Boston’s position as the commercial hub of New England” - only “new markets” could “revitalize the economic life of Boston and return her to leadership” which was what the Middlesex Canal allowed – that the Canal is further understood and proclaimed to have been the chief reason why Boston became the most important of all the mercantile centers in New England – and finally that the Canal was “largely responsible for the growth of Boston as a world city.”

All these claims, as our examination of Boston between the founding of the town to the Canal’s beginning, and then to the Canal’s collapse after 1835 as a desirable financial way to transport goods between Boston and the Merrimack region, rest on very shaky and weak historical facts. Indeed, as has been proven already, Boston and its port in its first three centuries was always, given the conditions and expectations of the time, a first class American “enterprise” – defining that term as an “activity that involves many people and that is often difficult” but ultimately successful.

For an accurate and honest summary of the Canal’s contribution to Boston and its port there is none better than that expressed by Benjamin W. Labaree in his essay “The Making of an Empire: Boston and Essex County, 1790-1850.” There he concluded that, “The Middlesex Canal succeeded in its immediate objective of diverting the flow of at least some of the interior New Hampshire’s resources to Boston. It brought down lumber, cordwood for fuel, and other wood products like shingles and clapboards. Cargoes of ship timber made possible the establishment of Thatcher Magoun’s famous shipyard on the Mystic River at Medford. Shippers could move their bulk commodities by the canal at half the cost of transportation by land and were therefore in a better position to compete with coasting vessels that brought similar goods from Maine. Shippers could also patronize teamsters as a competitive alternative because of their ability to deliver door-to-door. (23) Upstream cargoes, on the other hand, remained difficult to obtain until after the establishments of mills at Lowell, Massachusetts, and Nashua and Concord, New Hampshire, which provided larger markets.” (24)

He further goes to say, “In a larger sense, however, the Middlesex Canal had a significance that reached beyond its modest economic role. It was America’s first complex waterway. Builders of other canals, most notable those who constructed the Erie Canal, learned many lessons from Boston’s pioneering effort. And if the Middlesex Canal did not exactly open up the interior of New England to the merchants of Boston, it surely helped to rekindle interest in the project to connect western Massachusetts with the coast of Boston.” (25)

Complementing Labaree’s historical understanding on this matter is the one that I wrote, without knowledge of his essay, for the entry “Boston” in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of the American Enlightenment, which reads in part: “At the start of 1775 Boston’s population was about 15,000; after the British left the city in 1776 it was about 3,000. This affected its once busy commercial port, the business’ that depended upon it, and needed to be immediately reinvented. Bostonians met that challenge and by 1800 the town’s population had climbed to 25,000 and its wharfs, shipyards, trading houses were again flourishing. New business ventures were undertaken and entrepreneurs abounded. Thomas Handasyd Perkins launched his shipping firm and his vessels carried tea, cloth, china, slaves, coffee, sugar, furs and opium all over the world and made him an extremely wealthy merchant philanthropist.

Frederic Tudor, ‘the Ice King,’ became very rich by cutting ice from various Greater Boston ponds and lakes and shipping it to the tropics, the Southern states, and eventually to India. In doing so he introduced the country to the idea of refrigeration. Among the most significant enterprises of this period under the leaderships of Colonel Loammi Baldwin and Attorney General James Sullivan was the construction of the Middlesex Canal. Opened in 1803 it was one of the earliest major American canals and enabled the Port of Boston to be connected for the purpose of trade and transportation via the Merrimack River with New Hampshire and Vermont. The lessons learned and the equipment developed in building this canal contributed to the development of the civil engineering profession in the United States.” (26)

We have in this essay tried to understand the roles played by Boston, its Port, and the Middlesex Canal, as they relate to the fact that from its beginning Boston was the leading business and trade center for the New England Region. Hand in hand with that attempt we have tried to describe exactly what the Middlesex Canal’s contribution was in this matter. The conclusions reached, I believe, do just that. However, there is in the historical understanding another very significant ingredient not yet discussed.

That basic fact has been accurately stated by Bernard Bailyn in his essay “Slavery and Population Growth in Colonial New England.” There he asks this question: “How was it that this unpromising, barely fertile region, incapable of producing a staple crop for the European markets, became as economic success by the eve of the Revolution?” How indeed!

The answer was the institution of slavery. He summarizes that fact in these words: “The most important underlying fact in this whole story, the key dynamic force, unlikely as it may seems, was slavery. New England was not a slave society. On the eve of the Revolution, blacks constituted less than 4 percent of the population in Massachusetts and Connecticut, and many of them were free. But it was slavery, nevertheless, that made the commercial economy of eighteenth-century New England possible and that drove it forward. As Barbara Solow and others have shown, the dynamic element in the region’s economy was the profits from Atlantic trade, and they rested almost entirely, directly or indirectly, on the flow of New England’s products to the slave plantations and the sugar and tobacco products industries that they serviced. The export of fish, agricultural products and cattle and horses on which the New England merchants’ profits mainly depended reached markets primarily in the West Indies and secondarily in the plantation world of the mainland south. Without the sugar and tobacco industries, based on slave labor, and without the growth of the slave trade, there would not have been markets anywhere nearly sufficient to create returns that made possible the purchase of European goods, the extended credit, and the leisured life that New Englanders enjoyed. Slavery was the ultimate source of the commercial economy of eighteenth- century New England. Only a few of New England’s merchants actually engaged in the slave trade, but all of them profited by it, lived off it.” (27)

It is with this broader understanding of slavery in mind that we now turn our thinking to the question of American slavery and the Middlesex Canal.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Samuel Eliot Morison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts 1783-1860 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1921) 216.

(2) Michael J, Connolly, Capitalism, Politics, and Railroads in Jacksonian New England (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003) 77-8.

(3) Diana Muir, Reflections in Bullough’s Pond Economy and Ecosystem in New England (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2000,) 112.

(4) Google New England Historical Society, Topic The Middlesex Canal, New England’s Incredible Ditch.

(5) Mary Stetson Clarke, The Old Middlesex Canal (Melrose, MA: Hilltop Press, 1974) 12-3.

(6) Bernard Bailyn The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1955) 83.

(7) Ibid., 95.

(8) Boston Looks Seaward The Story of the Port 1630-1940, Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Massachusetts, Sponsored by Boston Port Authority (Boston, Bruce Humphries, 1941) 285. [There also is a 1985 Northeastern University Press reprint available]

(9) Ibid. See too Margaret Ellen Sewell “The Birth of New England in the Atlantic Economy From Its Beginning to 1770” in Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2000) 48. There she concluded, “Boston dominated the coastal and regional colonial trades through most of the seventeenth century.”

(10) Jacqueline Barbara Carr, After the Siege A Social History of Boston 1775-1800 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2005) 13.

(11) Ibid., 40.

(11) Ibid., 153.

(12) Ibid., 162.

(13) Ibid,. 42.

(14) Ibid., 230.

(15) Boston Looks Seaward The Story of the Port 1630-1940, 86.

(16) Samuel Eliot Morison, The Maritime History of Massachusetts 1783-1860, 50.

(17) Ibid., 25.

(18) Ibid., 187.

(19) Ibid., 207.

(20) Ibid.

(21) Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2000) 1. Economic and sociological scholars also term the present business period as the “knowledge-based economy.”

(22) Harry C. Dinmore, “A Comparison of the Pawtucket and Middlesex Canals and the Boston and Lowell Railroad,” Towpath Topics, 7 (October, 1971).

(23) Robert F. Dalzell, Jr. in his Enterprising Elite The Boston Associates and the World They Made (NY: Norton, 1987) said that during the 1830s the Canal earned stockholders a 4 percent return on their overall investment of $746. While that sounds good those holding stock in turnpike companies, his example was the Salem turnpike, earned almost the same. For the Canal to do well it always needed tolls as high as they could be, but they more than often had to be kept low in order to encourage use and to compete with the turnpikes.

(24) Entrepreneurs The Boston Business Community 1700-1850. Eds. Conrad Edick, Wright, Katheryn P. Viens (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1997) 347-8.

(25) Ibid.

(26) Alan Seaburg, “Boston” in The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of the American Enlightenment, ed. Mark G. Spencer, 2 vols. (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015) 162.

(27) Bernard Bailyn, “Slavery and Population Growth in Colonial New England,” in Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2000) 254.

The following interlude is reprinted from Alan Seaburg’s e-publication A Social History of the Middlesex Canal.

INTERLUDE TWO: THE CANAL 1814

Middlesex canal connects the Merrimac with Boston harbor, the whole distance is 30 miles; viz. 6 miles from the Merrimac to Concord river, and 25 thence to Boston harbor. Concord river is a sluggish stream, and has a fall in it, in the town of Billerica, 4 miles from its mouth. The canal commences in the Merrimac, a little above Patucket falls; and, in a southeast course of 3 miles, ascends, by 3 locks, 21 feet, to the level of Concord river above its fall. It crosses Concord river on its surface; and, in a southeast course of 25 miles, descends 107 feet by 13 locks, to the tide water of Boston harbor. The locks are all 90 feet by 12, of solid masonry, and excellent workmanship. The width of the canal is 24 feet, and draws 4 feet water. Both parts of the canal are fed by Concord river. From that river, southward, it preserves the same level for the first 11 miles. In this distance, it was necessary to dig, in some places, to the depth of 20 feet; to cut through two difficult ledges of rocks; and to throw several aqueducts across the intervening rivers. One of these, across the Shawshine, is 280 feet long, and 22 feet above the river. There is another across Mystic river, at Medford. At the end of the 11 miles from Concord river, is a lock with 7 feet descent, and a mile and a half farther another of the same height. Thence to Woburn the canal is level. Boats of 24 tons, 75 feet long and 11 wide, can navigate it. They are generally, however, smaller, and are drawn by two horses, at the rate of 3 miles an hour. Common boats pass from one end to the other in 12 hours. A raft, one mile long, and containing 800 tons of timber, has been drawn by two oxen, part, of the way, at the rate of one mile an hour. The whole expense of the work was above $550,000. The tolls have not exceeded $17,000 per annum. The vast quantities of timber around Wmnipiseogee lake, on Merrimac river and its branches, and Massabesic pond, and the produce of a great extent of’ very fertile country, will, in the end, be transported on this canal to Boston. It need not be added, that this is the greatest work of the kind yet completed in the United States.

Morse’s Universal Geography, 1812

AMERICAN SLAVERY AND THE MIDDLESEX CANAL

Recent investigations, and the scholarly studies that they have produced, reveal just how many slaves were captured, brought, and sold to American and other buyers. The number is staggering, and many more than most people have ever thought. Our current understanding is that between 1554 and 1866 at least 35,000 slave voyages took place in the Atlantic world, and that these ships of horror brought to the New World from the continent of Africa 12 million human beings. In the 1790s alone ”one large slave vessel left England for Africa every other day.” (1) That almost unimaginable figure still remains difficult to contemplate or accept in a land where we boast that freedom, justice, and hope for all exists “from sea to shining sea!”

So from the first days of the European colonization of the New World, especially the area we take pride in terming the land of the “free,” white people allowed and promoted the enslavement of some of its people, most notably those whose skin was not white. In order to truly understand our history this basic reality needs to be accepted. To deny it means to understand falsely every era of our common story.

This approach to learning our history extends to every period of its story, and so this essay on American slavery and the Middlesex Canal, for it too has wrapped around its operation the destructive veins of slavery, and its first-born child racism. Of this truth there can be no doubt, just as there can be no question that for all of those living in Boston and New England - merchants, traders, bankers, insurers, clergy, politicians, educators, and those who sailed on its ships or worked in its factories, really everyone - were for better or worse a part of the evil fostered by the practice and toleration of slavery in the United States.

“Historians of early New England,” the authors of New England and the Sea declared, “have been slow to recognize how much of the region’s prosperity depended upon the institution of slavery. Black servants were employed as carpenters in shipyards, as longshoremen and truckmen along the waterfront, and as mariners aboard vessels. Even more significant was that the tobacco, rice, and sugar plantations of the southern and West Indian colonies constituted the major market for New England produce such as fish and timber.

Those Yankee merchants who prospered in the plantation trade were as much dependent on the institution of slavery for their riches as were the planters themselves. Some New England merchants, the slave traders, relied even more directly on human bondage for their business profits. Perhaps as much as 30 percent of the Africans imported into the continental American colonies made the notorious middle passage ‘tween- decks on a Yankee-owned slaver. Still other New Englanders counted on selling much of their rum to British and American merchants directly engaged in the slaving business. The coffers of some New England’s proudest families were filled with profits from this trade.” (2)

From that generalized statement about New England and slavery we turn to one that is more local: its influence upon the town of Newburyport, Massachusetts. The source here is Susan M. Harvey’s 2011 Fitchburg State University’s M.A. thesis on “Slavery in Massachusetts.” Here is her summary of her study: “This thesis examines the connections between Newbury and Newburyport, Massachusetts, and the transatlantic slave trade beginning with Newbury’s founding in 1635 to the early nineteenth century. The ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery is often associated only with the southern United States, but its economic impact was felt throughout all of the North American colonies/states, particularly in New England. By examining the livelihoods, trading practices and estates of the residents in these towns, I make clear that their economy was inextricable linked to the trading of Africans and to slave-made goods. I have focused my research on shipbuilding, specifically the building of vessels for slaving; the trade of New England- grown goods with the West Indies that continued into the nineteenth century; and the distilling of molasses into rum, which was used to purchase Africans. Challenging the argument that because there were so few slaves in New England there was no involvement with the slave trade, this thesis adds to the growing body of work on the subject of New England’s complicity in the crime of buying and selling human beings and perpetuating the slave trade thorough its trading practices. The economy of New England was completely dependent on the slave-based plantation economy and the transatlantic slave trade.” (3)

What was true for Newburyport was just as true for its close inland neighbor Billerica whose early history also reflected a slave basis. Christopher M. Spraker recounts that in detail in his article, “The Lost History of Slaves and Slave Owners in Billerica, Massachusetts, 1665-1790.” While his study concerns both the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and not the active decades of the Middlesex Canal, it does provide us with a good insight into the lives of individuals and families who in the early nineteenth century had their roots and heritage in a town enriched in several ways by slavery.

Spraker wrote of such Billerica people, families and their slaves that their lives “were entangled in a series of important family connections. While these connections were more often than not detrimental for the enslaved, they helped to link prominent Billerica individuals and families in a web of personal and economic relationships within the town and beyond. To put it succinctly, in addition to possessing a degree of economic independence and valuable free time, slave owners in Billerica also possessed the family background required to pursue positions of influence within their community.” (4)

Now let us focus our study directly on the Canal itself, and the money its stockholders and employees made, first from shipping raw cotton brought from southern cities to the Port of Boston, and then barged to the cotton textile mills of Lowell, and secondly returned again to Boston merchants to be sold as finished cotton cloth.

As far as we know today, and that could always change, there are no records indicating that even one slave dug a shovelful of dirt to create the bed of the incredible ditch. However there can be no doubt that the cotton the Canal transported was planted, tended, and picked by slaves, who had been captured in Africa, put in chains, packed into ships, and brought to our country where they were then forced to work for those who “owned” them.

Sven Beckert, the Laird Bell Professor of American History at Harvard, in his monumental study Empire of Cotton A Global History pointed out that between 1000 and 1900 CE cotton was “the world’s most important manufacturing industry.” In his discussion on Boston and the Merrimack region, the focus of this essay, he stated, “Huge fortunes were invested in cotton manufacturing as merchant capital attached itself to industrial production. The most dramatic such move was undertaken by a group of Boston merchants looking for new outlets for capital suddenly and ruinously idled due to the American trade embargo against Britain and France from 1807 to 1812. In 1810 Francis Cabot Lowell traveled to the United Kingdom to acquire the blueprints for a cotton mill. Upon his return, he and a group of wealthy Boson merchants had signed the ‘Articles of Agreement between the Associates of the Boston Manufacturing Company,’ which created a huge integrated spinning and weaving mill in Waltham near Boston, initially capitalized at $4,000,000, or a bit more than 2 million francs. The mill focused on inexpensive coarse cotton goods, some of which were sold to clothe slaves, replacing Indian manufactured cloth. (So common did Lowell cloth become among slaves that ‘Lowell’ became the generic term slaves used to describe coarse cottons.) The venture proved hugely profitable, with dividends in most years above 10 percent on the paid-in capital. In 1817, the mills paid peak dividends of 17 percent. By 1823, the Boston Associates expanded further, building more mills in Lowell, about twenty-five miles north of Boston, and creating the largest integrated mills anywhere in the world. This move of American merchant capital into manufacturing marked another tight connection between slavery and industry.” (5)

Peter Temin in Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England shared Beckert’s understanding of the general background of how Massachusetts became engaged in the cotton and textile business. “The initial investments in the cotton textile industry,” he declared, “were made by New England merchants from Boston and Salem in an informal market. These men had earned great fortunes from trade with Europe, the Caribbean, and China. Such trade had been halted by the Embargo of 1808, however -- the embargo that led to the War of 1812 with Britain –- and the merchants were looking for a domestic outlet for their capital. The nascent cotton industry fit the bill. The tradition of Boston merchant families investing in cotton mills was familiar by 1830.” (5)

Lowell, Massachusetts grew out of the town of East Chelmsford, the original terminus for the Middlesex Canal. It was name for Francis Cabot Lowell, the textile businessman and merchant already mentioned, and was incorporated in 1823 as a town and in 1836 as a city. Fortunately there exists a number of very reliable studies about Lowell and cotton, but for this essay I want to focus on just one: Cotton Was King: A History of Lowell, Massachusetts. It is a collection of essays about the community, which Arthur L. Eno, Jr. edited in 1976. I selected it for several reasons, but chiefly because Eno was a founding member and first president of the Middlesex Canal Association (1962-72), and so knew the history and the importance in its time of the Canal.

In his chapter of the Lowell history Eno wrote, “During the decades preceding the Civil War, King Cotton dominated the thinking, as well as the economy, of the city of Lowell. The Boston Associates and their successors, the manufactures of Lowell, had many personal contacts with the South: business dealings, cotton buying trips, and visits by Southerners to Boston and by Bostonians to the South. . . . The relationship was profitable and both the Yankee ‘Lords of the Loom’ and the slave-holding ‘Lords of the Lash’ hoped to continue it.” (7)

Indeed the entire New England Region was hospitable to cotton and in 1835, for example, the Port of Boston alone received 90,109 bales of cotton from southern states. No wonder New England folks were proud that the region could produce cotton goods more cheaply than elsewhere in America. Now if Lowell textile mill owners and Boston merchants were made happily rich thereby, it proved also a boon to the Middlesex Canal stockholders, personnel, and employed workers too. For the transportation of raw cotton to Lowell and cotton cloth goods back to Boston via the Canal significantly improved, and increased, the yearly revenue that kept the Canal financially “afloat” during a good portion of its history.

So while many of the boats going down stream carried cords of wood, bricks, firewood, potash, and granite, for examples, those on the return trip regularly hauled “cotton, grown in the South and shipped to Boston, machine parts, and even entire textile machines, some so wide that mill agents worried whether they would fit through canals’ locks.” (8) And while it should be noted that not all the cotton needs of Lowell came by the “Canal” – some of it was teamed – most of it did. Therefore, it was in everyone’s best interest to see to the continued prosperity of Lowell’s cotton business, in spite of the fact that its financial success was clearly based on the institution of American slavery.

Eno stressed in his study that term “everyone” as regards the wide spread, almost universal really, effect of slavery upon all those then living, The stain of human enslavement cannot be conveniently assigned, as many would like to have it, just to those with power and money. Its insidious evil is shared by every man and woman. “The same attitude,” Eno observed, “prevailed among the lesser figures in the cotton textile industry in Lowell. It was felt by overseer and loom-fixer alike that the city’s continued prosperity, as well as their own, depended on the continuance of the friendly and cooperative relationship with the southern cotton-growers. If for any reason the flow of raw cotton into Lowell stopped, the mills would be forced to close, and all would be out of work.” (9) It would also hurt badly the financial bottom line of the Canal.

It is no wonder then that the abolition of the institution of American slavery was neither welcomed nor embraced in Lowell. Yet the city had those who were in favor of abolition as well as those who opposed it, and they did attempt to publically support their cause. In 1834, for an example, when George Thompson a prominent British abolitionist, was invited to give three lectures on that topic in Lowell, opposition arose not only from the business community but also from the mill workers. On the third day of the lectures placards were posted throughout the community saying in part: “Citizens of Lowell, arise! Look well to your interests! Will you suffer a question to be discussed in Lowell which will endanger the safety of the Union? –and a question which we have not, by our constitution, any right to meddle with.” (10)

Let us now summarize as bluntly as possible cotton, slavery, and the Canal. Cotton during the Canal’s life span was grown in the South. There the seeds were planted by slaves, harvested by slaves, and loaded onto the boats bound for Boston Harbor by slaves. Growing it and shipping it North then made for the white plantation owners and their families, for the white ship owners and their families, for the white Boston merchants and their families, and for the white directors, proprietors, and workers of the Middlesex Canal Corporation and their families, a handsome profit and for some a handsome life style. And, not to be ignored, the same was also true for Lowell’s white mill owners, millworkers, and their families!

Cotton, if a very clear and major example of the direct relationship between slavery and the Canal, was not the only such connection. Another was the “hogsheads” of molasses that the Canal freighted. Molasses, was part of the “Triangle Trade” that at this time was carried on between Western Europe, West Africa, the Caribbean, and the American Colonies. That trade focused on slaves, manufactured goods, and such cash items as sugar and molasses. The ships involved usually started from Western Atlantic ports to which they eventually returned to begin the trip once again. Molasses was made from sugar cane grown, tended and cared for, then picked by slaves. Medford town, through which the Canal flowed and whose businessmen were some of those who first initiate planning for the Canal, was busily engaged during canal days in making bricks, sailing ships, and rum. Indeed Medford rum was world famous and its molasses came from the Caribbean. And while sold throughout the Atlantic Region it also sailed up the Canal to New Hampshire. Indeed, many a bargee or pleasure voyager while traveling the Canal enjoyed stopping for a nip of Medford rum at one of the many Canal’s taverns. In doing so they were, along with those who made it and sold it, stained by the “Peculiar Institution.”

One final brief example of slavery’s influence on the Canal and the New England Region involved the lumber for ships and ship masts that the Canal transported from the forests of New Hampshire to the shipyards of the Boston area, and really beyond. The transport of lumber to Boston was one of the chief products carried on the Canal, and that lumber translated into the building of ships, a goodly number of them, which translated into slave ships. Kristin Thoennes Keller put that fact succinctly when he wrote, “The New England Colonies were a shipbuilding area. Slave ships left New England with many items. The slave ships carried horses, hay, peas, beans, corn, fish, and dairy products. Lumber, lead, and steel were also loaded onto the ships. The slave ships sailed to the West Indies. These ships traded their goods for rum. From the West Indies, they sailed to Africa to trade the rum for slaves. Once loaded, they sailed back to the West Indies with new slaves.” (11)

Hugh Howard in his essay about the Royall House in Medford, and the family who owned it, came to the same conclusion on this matter. “Most slave ships,” he declared, “ were built in the region, and the bulk of the exported livestock, sawn boards, and grains went to the Caribbean to support the production of sugar, the raw material essential to the making of rum, the favored medium of exchange for buying slaves. More than four-fifths of the rum distilled went to Africa.” (12)

So the impact with what began with the hunting down of individuals living on the continent of Africa spread, as New Hampshire maple syrup does when spilled on the floor, far and wide. In this way it in time embraced the act of floating New Hampshire lumber between the banks of the Canal, which was then used to build some of the very ships that carried slaves to the “New World.”

Therefore, as David Richardson pointed out in his article “Slavery, trade, and economic growth in eighteenth-century New England,” this area “may never have been a slave society in the conventional sense of the term” but “its trade with slave- based economies, whether within or outside the British Empire . . . played a far more significant role in promoting the growth in late colonial and early national New England” than earlier historians and most of us today like to believe or accept. (13) And more than being an event of past generations American Slavery lives on today in the racism that still mars “the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

So to fully appreciate the story of the Canal, and its accomplishments and contributions to its immediate region, and indeed far beyond that geographical limit, one has to understand how it benefitted on several levels from American slavery. Yet at the same time it is just as vital to acknowledge that the merchant marine business, and its workers, must also be seen as a mixture of the “good” and the “bad” in the daily life of people at every period of our history and story. Most women and men of all generations cannot be viewed as either “pure virtue” or “pure evil.” While Boston merchant Thomas Handasyd Perkins made money from slavery and opium, and that is a part of his biography, another part of it is his involvement in helping to establish today’s Perkins School for the Blind.

The authors of New England and the Sea put is this way, “To write off the merchants of the period as selfish and narrow-minded, with no feeling for the world beyond the coutinghouse, would be unfair” for “merchants supported a full range of important civic and educational activities, such as parks, schools, and libraries. They patronized the traveling companies that gave frequent musical and theatrical performances. Under their encouragement the seaports of New England emerged from an earlier status as provincial country towns to become cosmopolitan centers of culture and learning.” (14) And, in their individual ways, so did most of the people of those generations.

We who love the Canal as we consider this topic might well keep in mind these words of Drew G. Faust, the president of one of America’s most significant universities, spoken during the opening years of the twenty-first century as Harvard had to confront its historic role with American slavery. “This is our history and our legacy,” she stated, “one we must fully acknowledge and understand in order to truly move beyond the painful injustices at its core.” (15)

FOOTNOTES

(1) Bernard Bailyn, Sometimes An Art Nine Essays on History, (NY: Knopf, 2015) 6.

(2) Robert G. Albion, William A. Baker, Benjamin W. Labaree, New England and the Sea (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1972) 37.

(3) Susan M. Harvey, “Slavery in Massachusetts: A Descendent of Early Settlers Investigates the Connections in Newburyport, Massachusetts” (M.A. thesis, Fitchburg State University, 2011) 1.

(4) Christopher M. Spraker, “The Lost History of Slaves and Slave Owners in Billerica, Massachusetts, 1665-1790,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 42 (January, 2014) 109-24.

(5) Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (NY: Knopf, 2014) 145.

(6) Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise An Economic History of New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2000) xvii, 147.

(7) Arthur L. Eno, Jr. ed., Cotton Was King: A History of Lowell, Massachusetts (Somersworth, N. H.: New Hampshire Publishing Company, 1976) 127.

(8) Theodore Steinberg, Nature Incorporated Industrialization and the Waters of New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1991) 5.

(9) Eno, Cotton Was King, 127.

(10) Ibid., 128.

(11) Kristin Thoennes Keller, The Slave Trade in Early America (Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press, 2004) 32.

(12) Hugh Howard, “The Remains of a New England Plantation Reveal a Side of Colonial Life The History Books Forgot to Mention,” Tufts Magazine (Summer 2010).